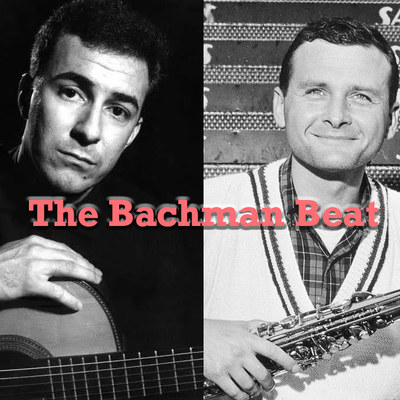

Tal Bachman: Remembering Getz/Gilberto

by Tal Bachman

The Bachman Beat

It's Monday morning, March 18, 1963. Blustery day. New York City. Three Brazilians—two men and a woman—take a cab to a building at 112 West 48th Street. The sign on the building says, "Manny's". It's New York's premier music store.

But the Brazilians aren't interested in buying any instruments. They walk up three flights of stairs to the fourth floor, directly above Manny's, where they enter a recording studio.

There, a young recording engineer named Philip Rabinowitz greets them. So does Verve Records producer Creed Taylor. Jazz saxophonist Stan Getz arrives shortly thereafter, with a bassist and drummer in tow. The three Brazilians are composer and pianist Antonio Carlos Jobim; his friend, guitarist and singer João Gilberto; and Gilberto's 22 year old wife, Astrud. Antonio and João are there to record an album with the American musicians. Astrud is tagging along just to watch.

The studio itself isn't much. It's a simple, high-ceilinged room with fairly basic recording equipment. It doesn't cost much to rent. For more polished recordings, musicians go to one of New York's fancier recording studios—the kind with top-of-the-line recording machines, dozens of mics, strategically built-in sound baffling, miniature echo chambers, slick glass, fine carpets, wood paneling, fancy reception area, lounge with a pool table, and a mixing room acoustically-tuned so as to minimize odd frequency pockets. This one, at least up until very recently, musicians visit only to record rough, or "demo", versions of their new songs.

But recently, some good records have come out of the spartan little affair in midtown Manhattan. Its reputation is growing. Musicians are starting to book it to make real records.

After all, Philip—the house engineer and minority co-owner of the operation—is easy to work with. And he knows his stuff. The room itself—precisely because it hasn't been professionally redesigned to deaden or balance the acoustics—retains its natural, idiosyncratic sound. That unique sound comes through the microphones just enough to lend a certain character to all the music recorded at the studio. And right next door to the building is Jim & Andy's Bar, a watering hole increasingly popular with musicians in town. Word has it that Charlie Parker had a drink there once. Or was it Chet Baker? Or John Coltrane? Rumors have started to fly, but the attraction of them all, to New York musicians, is that if you book a session at Philip's new studio, you might just bump into one of the world's greatest musicians during a break down at Jim & Andy's. Maybe you could even become friends. You never know.

And so, the little studio has started to make its mark. And as a result, much to the delight of young Philip, Verve Records has rented his A & R Studio for this two day project with the Brazilian and American musicians.

Producer Creed and engineer Philip—who has decided to change his last name from Rabinowitz to Ramone—spend that day and the next recording various versions of eight songs. The songs don't quite sound like standard jazz. They don't quite sound like samba, either. They're best categorized as belonging to a new genre called bossa nova (literally, "new wave"), developed by Jobim himself, the man playing piano on the sessions, and the man who's written most of the songs on the album.

Now, you might ask: How the heck does anyone invent a whole new genre of music?

From a distance, we can guess the answer—you take bits and bobs from pre-existing styles, put them together in a new way, add in a couple of features of your own—and voila! You've just created your own new genre. It doesn't have to be radically different from other genres. It just has to be identifiably different. And that only takes a few little adjustments, in the same way that humans and chimps share 98% the same DNA. It's that two percent that makes all the difference.

But still...how do you invent a whole new genre of music? To know in theory what that looks like is one thing. To actually do it, and do it well—to create a brilliant new genre—that takes genius. But the man now sitting in Philip's studio, playing piano, Antonio Carlos Jobim, is just such a genius. He's actually done it.

Sure, he's had help. He's had musical ancestors and colleagues. But for the most part, bossa nova is his thing. He's taken jazz chords, samba rhythms, classical guitar, light piano, his own unusual melodic and harmonic sense, put them all together, and come up with something new, fresh, and exciting. And supremely creative.

Here are a few specifics:

Jobim uses the same quirky little pulse to drive each song—accents on beat 2 and beat 3 and. Each song he writes is a marvel of casual-sounding complexity. The chords he uses include just about every combination of notes you could ever come up with: diminished chords, half-diminished chords, seven with a six on top, augmented chords, major sevenths with a flat five, seven flat-nines, seven sharp-nines, minor sixes, and dozens more, which he then strings together in alluringly strange sequences. He even throws in unexpected key changes, yet he always finds a way to get back to the original root chord.

Over and through all those strange and beautiful chords, he threads seductive, twisting melodies. His lyrics range from witty to wistful to deeply romantic. His instrumentation is string bass, light drums, classical guitar, piano, single vocal, and often a sax.

He plays around with standard song structures. For example, some of his songs have unusually long bridges—sometimes double or more the standard length. In others, the melody and chords change slightly on the final verse. He uses enough repetition in each song to make it memorable, but more variation than you ever hear in a standard jazz or popular song. Back to the recording:

The American and Brazilian musicians at the studio record various takes throughout the day. The sax player Getz, the son of impoverished, Ukrainian-Jewish immigrants, is a difficult man to work with. He's nasty, short, mercurial, stingy, and damaged from past drug addiction, incarceration, and a challenging childhood. Yet somehow, the musicians manage to forge on, hour after hour. And surprisingly, the cantankerous Getz turns in some of the most evocative, emotionally compelling sax solos ever recorded.

The recordings progress as expected until a lyricist arrives with English translations for two of Jobim's songs. Sensing an opportunity to spice up the album, producer Creed Taylor decides someone should sing those two songs in English. But he also says he wants to get the record done on schedule—that is, by the second day of recording.

Maybe the solution, he thinks, is for João's wife Astrud to try singing them. She isn't a professional singer, but she's in the studio, and she can speak English. It's worth a quick shot. Astrud obligingly steps up to the mic and sings "Girl From Ipanema" and "Quiet Nights of Quiet Stars". The effect is instant. Creed loves what he hears. Astrud doesn't sound like any other singer he's ever heard. She certainly doesn't sound like a jazz singer. Her voice is almost entirely devoid of affectation—no vibrato, no trills, no acrobatics. She sounds utterly guileless. She also sounds charming, feminine, alluring, innocent, and intimate. It perfectly fits the music. It's magic.

The musicians finish the album. To their frustration, Verve Records sits on it for the next year, afraid it will bomb. But when Verve finally releases it a year later under the title Getz/Gilberto, "Girl From Ipanema" becomes a smash. Astrud Gilberto becomes famous and begins a long singing career. The album hits #5 on the Billboard charts, wins four Grammys (including Album of the Year), and makes saxophonist Stan Getz a rich man. It also puts the upstart A & R Studios squarely on the map, along with its young house engineer, now known as Phil Ramone. Phil in fact wins a Grammy—his first, but not his last— for his engineering on the album. Through his choice and precise positioning of mics around the room, his spacing of the players, and his clever use of EQ and compression, he has captured not just world class performances, but conveyed an intoxicating atmosphere of seductive intimacy.

Phil goes on to become one of the most successful record producers of all-time, winning fourteen Grammys, and selling hundreds of millions of records. (Just a few years after his work on Getz/Gilberto, Ramone also helps record a brand new band out of Canada. Called The Guess Who, it features my dad, Randy, on guitar. Ramone records the band's breakthrough song, "These Eyes" at A & R Studio's new location).

Beyond the commercial success and industry awards, Getz/Gilberto cements bossa nova's status in global music consciousness as a distinct, enduring genre. It also cements the characteristics of the genre: instrumentation, singing style, lyrical topics, chord progression styles, rhythm, vibe, etc. Jobim, with help from the Gilbertos and Stan Getz, does for bossa nova what Bill Monroe had earlier done for bluegrass, and what Bob Marley would later do for reggae: he establishes the phenotype.

There's something else—something more than just music. Getz/Gilberto, and bossa nova more generally, conveys a particular mood, attitude, life aesthetic—a way of being. The bossa nova world is unhurried. It's smooth. It's understated class—awesomeness without any exhibitionism (just like Astrud's voice). It's effortlessly sexy and devastatingly smart. It's a leisurely stroll along a warm beach by day, with cocktails (and romance) at night. It's not a tuxedo or a ballroom gown. It's not a ball cap with jeans. It's a tanned, fit guy wearing a crisp, casual collared shirt and well-fitting trousers, and a tanned, fit woman wearing light makeup and a dazzlingly simple dress. It's deep comfort with oneself and the world around you. It's an ultra-pleasant world within the world.

Some American musicologists will later claim that American jazz in essence created bossa nova. It would be much truer to say bossa nova re-created American jazz. No sooner did Getz/Gilberto hit than virtually every jazz songwriter began trying to write bossa nova-style songs, and virtually every jazz singer began adding bossa nova songs to his repertoire.

Here, for example, you can see Frank Sinatra perform a medley featuring "Quiet Nights of Quiet Stars" with Antonio Carlos Jobim. Here, you can see a joyously-sauced Dino play second fiddle to Caterina Valente in a performance of the Jobim song "One Note Samba". Sarah Vaughan, Tony Bennett, Sammy Davis, Jr., Ella Fitzgerald—you name 'em, they sang 'em. Even Andy Williams got in on the new craze. Almost everyone did. And almost everyone still does. To this day, it's hard to find a lounge act who doesn't roll into "Girl from Ipanema" at some point. Heck, I've done it myself during those late night impromptu jam sessions on the Mark Steyn Cruise, up in the Crow's Nest. You should come along with us next time and sing along.

In any case, in my books, Getz/Gilberto is a huge moment in the history of popular music. It's what really blasts bossa nova on to the world musical stage, and insinuates that difficult-to-define bossa nova way of being into popular consciousness. And it all came from a recording session sixty years ago this month.

Not bad for two days work.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/4ANZZOO62BCYVDHTH64TNRLJFI.jpg)