President Jimmy Carter bows during a prayer service for the hostages being held in Iran on November 15, 1979, at the National Cathedral in Washington.

Analysis by John Blake, CNN

Sun March 5, 2023

CNN —

Long before he was called a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, a humanitarian and the 39th president of the United States, Jimmy Carter was known as something else: a “Goddamn n***er lover.”

That’s the racial slur a White classmate of Carter’s at the US Naval Academy assigned to him right after World War II when the future president befriended the academy’s only Black midshipman.

Carter was called the same racial epithet when he took over his family’s peanut farm in South Georgia during the Jim Crow era. He repeatedly refused to join a segregationist group called the White Citizens’ Council despite threats to boycott his peanut business. A delegation representing the council confronted Carter at his warehouse one day, with one member even offering to pay his five-dollar membership fee.

“As one of his biographers has noted, Carter was so angry that he walked over to his cash register, pulled out a five-dollar bill, and declared: “I’ll take this and flush it down the toilet, but I am not going to join the White Citizens’ Council.”

Many people are sharing similar stories about Carter since the 98-year-old former president recently entered hospice care. As tributes to Carter pour in from around the globe, certain themes have emerged: his Christian faith, his childhood friendships with African Americans that shaped his views on race, and the founding of his Carter Center, which has cemented his post-presidency role as a peacemaker and ally of the poor.

But there’s another source of inspiration for Carter that’s been overlooked in many of the tributes – his distinctive brand of White evangelical Christianity, which remains hidden from most Americans.

Carter is a progressive White evangelical Christian. That may seem like an oxymoron, but it shouldn’t. Progressive White evangelicalism was once what one historian called “the ascendent strain of evangelicalism in America.”

Today White evangelical Christians are associated, rightly or wrongly, with a conservative set of theological and political stances. Those include opposition to abortion, being the most enthusiastic supporters of a brand of Christian nationalism that seeks to turn the US into a White Christian nation, and championing a former president who boasted about sexually assaulting women.

Yet there were periods in the 19th and early 20th century when White evangelical leaders led campaigns against slavery, fought for women’s rights and became leaders in an array of social justice reform movements.

Carter represents a religious tradition where a White evangelical could credibly claim to be a Bible-believing, “I’ve been saved by the blood of Jesus” Christian — and still be politically progressive, says Randall Balmer, author of “Redeemer: The Life of Jimmy Carter.”

Former President Jimmy Carter with his wife Rosalynn after teaching Sunday school class on December 13, 2015, at Maranatha Baptist Church in Plains, Georgia.Branden Camp/AP

“He had no problem being identified as a progressive evangelical,” says Balmer, who in his book recounts the story about Carter’s defense of a Black Naval Academy classmate and his refusal to join a White supremacist group.

“At one time, there was a strong element within the (Southern Baptist) Convention that would be identified as progressive evangelicalism, but now that’s pretty much been obliterated,” Balmer says.

Evangelicals are loosely defined as Christians who often share a “born-again” dramatic personal conversion, believe they’re supposed to spread their faith to others, and in Balmer’s words, either take the Bible “seriously or literally.”

To understand how and why Carter represents what one commentator calls the “road not taken” by many contemporary White evangelists, it’s helpful to look at two aspects of the former president’s religious beliefs.

He’s split with many evangelicals by speaking up for women’s equality

Less than a week after Carter entered hospice care, the Southern Baptist Convention decided to expel one of its largest and most prominent churches because it installed a woman as pastor. The church was founded by Rick Warren, author of the best-selling book “The Purpose Driven Life.”

To critics, the group’s decision offered further evidence that many White evangelicals do not believe in women’s equality. The convention is the largest Protestant denomination and has nearly 14 million members. It has often been described as a “bellwether for conservative Christianity.”

Many evangelical churches cite scriptures such as 1 Timothy 2:12 (“I do not permit a woman to teach or to exercise authority over a man; rather, she is to remain quiet.”) Critics also cite many White evangelicals’ opposition to abortion rights as reflective of a theology that does not respect a woman’s body or mind. Many White evangelicals counter that by saying abortion is the murder of an unborn child.

Carter’s progressive evangelism represents another view.

Carter, who spent decades as a Sunday school teacher, has said that the Bible permits women pastors and deacons. He also says Jesus treated women as equals and that women played a central role in the church’s early formation, including being the first to spread the news of the resurrection.

President Jimmy Carter raises his fist as he stands with his wife, First Lady Rosalynn Carter, after addressing the 118th annual National Education Association (NEA) Convention in Los Angeles on July 3, 1980.NewsBase/AP

His views on abortion have been more nuanced. He has said he’s personally opposed to abortion, but did not campaign to overturn Roe vs. Wade and opposed a proposed Constitutional amendment to invalidate the Roe decision.

His actions as president offered more concrete evidence of his belief in women’s equality.

Balmer says Carter was a feminist who appointed more women to his administration than any other president before him. Carter supported the Equal Rights Amendment, a proposed change to the Constitution that would have guaranteed legal equality to women. Former President Ronald Reagan, a White evangelical hero, opposed the amendment, which eventually failed.

Carter’s respect for women’s equality also could be seen in his relationship with his wife, Rosalynn Carter, some of his biographers say. When he was president, she sat in on his cabinet meetings and major briefings. By many accounts, she was his most trusted political adviser.

Elizabeth Kurylo, who extensively covered Carter during his post-presidency as he traveled the world on peacekeeping and humanitarian missions, says Carter valued the opinion of his wife.

“He views her as his partner – period. That is genuine,” says Kurylo, a former reporter with the Atlanta Journal Constitution. “She was his partner with him on every trip, and in the room with him on every trip. She doesn’t always agree with him – even though I never saw a disagreement, I know she would tell him what she thought.”

In 2000, Carter’s differences with contemporary White evangelicalism became so acute that he cut ties with the Southern Baptist Convention after it barred women pastors and publicly declared that a woman should “submit herself graciously” to her husband’s leadership.

“I personally feel the Bible says all people are equal in the eyes of God,” he said at the time. “I personally feel that women should play an absolutely equal role in service of Christ in the church.”

Yet the most profound source for Carter’s belief in women’s equality was non-religious. It was his mother, Lillian Carter.

Jimmy Carter gets a hug from his mother Lillian Carter, as he arrives home in Plains, Georgia, on January 20, 1981 -- the day Ronald Reagan succeeded him as president.Joe Holloway Jr./AP

She was a blunt, outspoken woman who stood up for Black people so much during the Jim Crow era in South Georgia that she was also called a n***er lover and her car was covered with racial slurs. She joined the Peace Corps at 68 and went to India to serve the poor.

Carter has called his mother the most influential woman in his life.

“I think more than any other person that I’ve ever known, my mother exemplified what is best about this country,” Carter said in a 2008 interview. “My mother was a registered nurse and … she treated African Americans exactly the same as she did White people and she was unique, perhaps among the 30,000 people that lived in our county, in doing that. I was filled with admiration for my mother.”

He embodies a brand of faith that once led the way on social justice

In October of 1978, Newsweek magazine put an illustration of Carter flashing his famous toothy grin on its cover with the headline: “Born Again!”

Today it’s common to hear White evangelical leaders take political positions and solemnly bow their heads with political leaders in prayer. But for much of the 20th century, White evangelicals zealously refrained from getting involved in politics by quoting scriptures such as Jesus saying his kingdom was “not of this world.”

It was Carter, though, who is arguably more responsible than any modern politician for rousing White evangelicals from their political hibernation. When he successfully ran for president in 1976, he introduced evangelical terms like “born again” into political discourse and talked openly about his faith in a way that no modern politician had before.

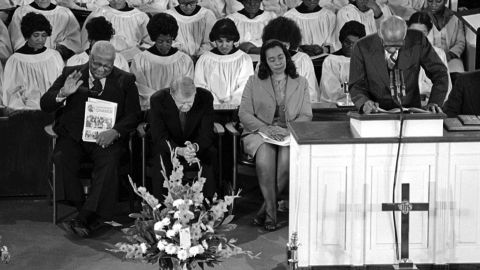

The Rev. Martin Luther King Sr., left, President Jimmy Carter and Coretta Scott King pray at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta on January 14, 1979. Carter that day was awarded the Martin Luther King Jr. Non-Violent Peace Prize.Jim Wells/AP

No other president had talked openly about his “personal relationship with Jesus Christ,” confessed in a famous magazine interview that “I’ve committed adultery in my heart many times,” and vowed that he would never lie to the American people.

Carter won the presidency in part because of support from White evangelicals who were delighted to see someone who looked and talked like them enter the Oval Office. Televangelist Pat Robertson claimed to have “done everything this side of breaking FCC regulations” to elect Carter in 1976, Balmer recounts in his book.

Images of Carter on his peanut farm, wearing jeans and an Allman Brothers Band T-shirt and quoting scripture, appealed to White evangelicals, says Nancy T. Ammerman, a sociologist and author of “Baptist Battles: Social Change and Religious Conflict in the Southern Baptist Convention.”

“The notion that this ordinary, church-going, non-coastal elite kind of guy could be president was exciting to people,” Ammerman says.

Yet Carter quickly fell out with many White evangelicals over issues that have come to define evangelical culture today: public stances on racism, homosexuality, abortion and the separation of church and state. To varying degrees, Carter disagreed with conservative White evangelicals on all those issues.

During Carter’s presidency, the Internal Revenue Service sought to enforce anti-discrimination laws at all-White Christian schools that many evangelicals had built to defy the Supreme Court’s landmark 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education ruling, which declared racially segregated schools unconstitutional, Balmer says.

To enforce the Brown decision, the IRS refused to grant tax-except status to schools like Bob Jones University in South Carolina that practiced racial discrimination, a move that White evangelical leaders unfairly blamed on Carter, Balmer says.

It was White evangelical opposition to racial integration, not abortion, that originally motivated many evangelicals to get involved in politics in the 1970s, Balmer says.

“They decided then to appoint Ronald Reagan as their political messiah,” Balmer says.

President Jimmy Carter shakes hands with Republican opponent Ronald Reagan after their debate on October 28, 1980, in Cleveland, Ohio. White evangelicals, after supporting Carter in 1976, drifted to Reagan in the 1980 campaign.Madeline Drexler/AP

Unlike former President Bill Clinton, another progressive White evangelical, Carter refused to “triangulate,” or adjust his beliefs to win favor with evangelicals.

“As other evangelicals drifted to the religious right, Carter advocated universal health care, proposed cuts in military spending and denounced the tax code as ‘a welfare program for the rich,’” wrote Betsy Shirley, an editor of Sojourners magazine, in a review of Carter’s book, “Faith.”

Walter Mondale, who served as vice president under Carter, recalled in an interview that when advisers told Carter to temper his policies to preserve his popularity, he refused.

“Many times the one argument that I would find would ruin a person’s case is when he’d say, ‘This is good for you politically,’” Mondale said. “He didn’t want to hear that. He didn’t want to think that way and he didn’t want his staff to think that way. He wanted to know what’s right.”

Carter would pay a political price for his idealism. White conservative evangelicals voted decisively for Reagan in the 1980 presidential election. These voters didn’t just turn away from Carter – they turned away from part of their own tradition, historians say.

That’s because during the 19th century, White evangelicals led the way on social justice issues. Evangelical leaders like Charles Finney fought against slavery, were active in prison reform, led peace crusades and were crucial in forming public schools to help less affluent children gain social mobility.

Former President Jimmy Carter and wife Rosalynn work on building a house in Maryland in 2010 as part of a nationwide project with Habitat for Humanity.Amy Davis/The Baltimore Sun/Tribune News Service/Getty Images

“They were also active in women’s equality, including voting rights, which was a radical idea in the 19th century,” Balmer says.

Those strands of progressive evangelicals survived well into the 20th century. During the 1960s and ’70s, Southern Baptists started to ordain women, passed resolutions supporting moderate pro-abortion stances and many members participated in the civil rights movement, Ammerman says.

Much of that progressive momentum dissipated, though, when conservatives gained control of the group in 1979 and the large White evangelical community aligned with the Republican Party. White conservative evangelicals eventually gained so much power that their dominance convinced many Americans that the only true evangelicals were conservative. Many forget that progressive White evangelists existed.

“He (Carter) does represent the road not taken by the denomination,” Ammerman says. “Through the ’60s and the ‘70s, the (Southern Baptist) denomination had been moving into a more progressive direction.”

He will leave behind a looming battle over the future of White evangelism

The road Carter took in his post-presidency has been more celebrated than his time in office. He has been called the most successful former US president, someone who built houses for the poor and traveled the world brokering peace.

“The world is a better place because of him,” says Kurylo, the former reporter who spent years traveling with and writing about Carter.

As the ex-president enters his last days, Kurylo says she doesn’t want to dwell on the end of Carter’s life.

Former President Carter speaks to the congregation at Maranatha Baptist Church before teaching Sunday school in his hometown of Plains, Georgia, on April 28, 2019. Carter taught Sunday school at the church on a regular basis since leaving the White House in 1981.Paul Hennessy/NurPhoto/Getty Images

“I chose to celebrate the impact that his remarkable life has had on the people in the world who will never know him,” she says. “What a remarkable life he’s had, and how wonderful it is that I got to observe it for 10 years.”

Part of what Carter will leave behind is the White evangelical subculture that nurtured him – and a looming battle over its direction. White Southern evangelicals, like other denominations, are leaving their churches in droves.

Some religious leaders now say that White evangelicals gained political power but lost their souls by aligning themselves too closely to a political party.

But Carter’s life may offer one final lesson.

He may have lost political power when he refused to curry favor with White conservative evangelicals while he was in the White House.

But perhaps he had another agenda: staying true to his faith.

The road Carter took proved to be the right one for him, and the innumerable people he helped along the way.

John Blake is the author of the forthcoming “More Than I Imagined: What a Black Man Discovered About the White Mother He Never Knew.”