Global: Protesters increasingly maimed and killed by police misuse of rubber bullets

Greater availability of ‘less-lethal’ weapons has led to rise in the use of force against protesters, with huge increase in eye injuries resulting in blindness

There were more than 440 eye injuries during 2019 protests in Chile, while some countries are using military-grade weaponry against protesters

A global torture-free trade treaty is urgently needed to regulate trade in policing equipment to help protect the right to protest

‘It’s shocking that UK companies are selling inherently indiscriminate and highly injurious military-grade weaponry to overseas law-enforcement agencies’ – Oliver Feeley-Sprague

Security forces across the world are increasingly misusing rubber and plastic bullets and other law-enforcement weapons to violently suppress peaceful protests, causing horrific injuries and deaths, said Amnesty International today (14 March).

In a jointly-produced 48-page report, My Eye Exploded, Amnesty and the Omega Research Foundation have called for strict new controls on the use of so-called “less-lethal” weapons and a global treaty to help properly regulate their trade.

The report, based on research in more than 30 countries over the past five years, documents how thousands of protesters and bystanders have been maimed - and dozens killed - by an often reckless and disproportionate use of such law-enforcement weaponry. This includes the use of kinetic impact projectiles - such as rubber bullets - as well as rubberised buckshot, and tear gas grenades aimed and fired directly at demonstrators.

Amnesty and Omega are among 30 organisations calling for a UN-backed torture-free trade treaty to prohibit the manufacture and trade in inherently-abusive kinetic impact projectiles and other law-enforcement weapons, and to introduce human rights-based trade controls on the supply of other policing equipment, including rubber and plastic bullets.

Patrick Wilcken, Amnesty International’s Military, Security and Policing Researcher, said:

“Legally-binding global controls on the manufacture and trade in less-lethal weapons, including kinetic impact projectiles, along with effective guidelines on the use of force, are urgently needed to combat an escalating cycle of abuses."

Dr Michael Crowley, Research Associate at the Omega Research Foundation, said:

“A torture-free trade treaty would prohibit all production and trade in existing inherently abusive law-enforcement weapons and equipment, including intrinsically dangerous or inaccurate single kinetic impact projectiles, rubber-coated metal bullets, rubberised buckshot and ammunition with multiple projectiles that have resulted in blinding, other serious injuries and deaths across the world.”

Devastating injuries and permanent disability

Weapons analysed in the report have caused permanent disability in hundreds of cases as well as numerous deaths. In particular, there has been an alarming increase in eye injuries - including eyeball ruptures, retinal detachments and the complete loss of sight - as well as bone and skull fractures, brain injuries, the rupture of internal organs and haemorrhaging, punctured hearts and lungs from broken ribs, damage to genitalia and psychological trauma.

In Chile, the policing of protests beginning in October 2019 resulted in more than 440 eye injuries, with over 30 cases of eye loss, or ocular rupture, according to the country’s National Institute for Human Rights.

In addition, at least 53 people died globally from projectiles fired by the security forces, according to a peer-reviewed study based on medical literature between 1990 and 2017. It also concluded that 300 of the 1,984 people injured suffered permanent disability, while the actual numbers are likely to be far higher. Since then, the availability, variety and deployment of kinetic impact projectiles has escalated globally.

Amnesty’s report underlines how national guidance on the use of kinetic impact projectiles rarely meets international standards on the use of force which stipulates that their deployment be limited to situations of last resort - when violent individuals pose an imminent threat of harm. Police forces routinely flout these regulations with impunity.

Eye injuries: An increasingly global approach to policing

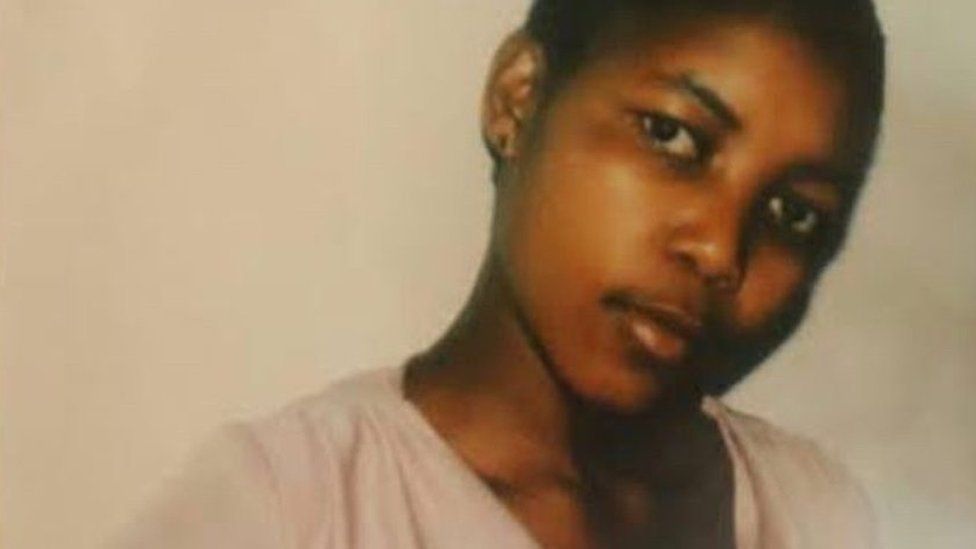

In April 2021, Leidy Cadena Torres, 22, was walking to a protest over tax changes in the Colombian capital Bogota, when she was hit in the face by a rubber bullet fired from close range by a riot police officer. She lost an eye. She said:

“I didn’t understand what was happening so I took out my phone and took a picture of myself, but I couldn’t see it. They try to injure you in a visible way, such as losing an eye, in order to scare people, so they don’t go out [and protest].”

Torres’s experience of being blinded has been repeated with alarming regularity in similar circumstances in south and central American states, Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and the USA during recent protests.

Gustavo Gatica, a 22-year-old psychology student, was blinded in both eyes after being hit in the face by rubber-coated metal pellets fired by police during inequality protests in Chile’s capital Santiago on 8 November 2019. To date there has been no accountability. He told Amnesty:

“I felt the water running from my eyes … but it was blood.”

He hopes his injuries will inspire change, to stop this happening to others, saying, “I gave my eyes so people would wake up.”

In the USA, use of rubber bullets to suppress peaceful protest has become increasingly commonplace. One demonstrator hit in the face in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in May 2020 told Amnesty:

“My eye exploded from the impact of the rubber bullet and my nose moved from where it should be to below the other eye. The first night I was in the hospital they gathered up the pieces of my eye and sewed it back together. Then they moved my nose back to where it should be and reshaped it. They put in a prosthetic eye - so I can only see out of my right eye now.”

In Spain, the use of large, inherently-inaccurate tennis ball-sized rubber kinetic impact projectiles has led to at least one death from head trauma and 24 serious injuries, including 11 cases of severe eye injury, according to Stop Balas de Goma, a campaign group.

In France, a medical review of 21 patients with face and eye injuries caused by rubber bullets documented severe injuries including bone fragmentation, fractures and ruptures resulting in blindness.

Amnesty has also documented cases of tear gas grenades being aimed and fired directly at individuals or crowds in Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, France, Gaza, Guinea, Hong Kong, Iran, Iraq, Peru, Sudan, Tunisia and Venezuela.

In Iraq, security forces have deliberately targeted protesters with specialist grenades which are ten times heavier than typical tear gas munitions, causing horrific injuries and at least two dozen deaths in 2019.

In Tunisia, Haykal Rachdi, 21, died after he was hit in the head by a tear gas canister in January 2021.

In Colombia security forces have deployed VENOM, a 30-tube grenade launcher, originally developed for the US Marine Corps, to launch volleys of tear gas grenades at protesters.

UK manufacturing of less-lethal weapons

At least two UK companies currently manufacture multiple-projectile kinetic impact munitions. The Lincolnshire-based company Centanex Ltd manufactures the CTX-BG CTX ball grenade, which the company says has been designed specifically for the requirements of various “UK police tactical firearms units and military users”.

The product data sheet lists applications for the grenade as including “public order/riot situations”. One model of the CTX ball grenade - the Ball Grenade 1.5s Stinger Balls - fires multiple small balls as kinetic impact projectiles.

Amnesty is calling for all multiple-projectile munitions - which are indiscriminate and overly-injurious - to be banned for use by law-enforcement agencies and for export.

Another Lincolnshire-based company - Primetake Ltd - manufactures a wide range of ammunition for use in public order situations which Amnesty also believes should be prohibited for such use and for export. The ammunition in question - all kinetic impact multiple-projectiles - are the firm’s following product lines: 2x18mm rubber ball round 12 gauge PT1587, 3x18mm rubber ball round 12 gauge PT3507, 9x8mm rubber ball round 12 gauge PT1588, and 12x8mm rubber ball round 12 gauge PT3523.

Oliver Feeley-Sprague, Amnesty International UK’s Military, Security and Police Programme Director, said:

“It’s shocking that UK companies are selling inherently indiscriminate and highly injurious military-grade weaponry to overseas law-enforcement agencies.

“International law-enforcement standards are clear that force should only be used as a last resort and in a strictly proportionate fashion, yet police forces around the world are still spraying crowds of people with multiple-projectile weapons.

“The Government needs to urgently strengthen the UK’s export control system to prevent the trade in abusive policing and security equipment, and ministers should support international moves to establish new legally-binding rules to ban this equipment globally.”