CHRISTIAN CRIMINAL CAPITALI$M

Bitter infighting threatens Kenya’s Methodist Church

At the center of a controversy that has been unfolding since 2015 is Presiding Bishop Joseph Ntombura.

NAIROBI, Kenya (RNS) — Disagreements within the Methodist Church in Kenya are threatening to tear apart the denomination, with some senior clergy seeking to form independent regional conferences.

At the center of a controversy that has been unfolding since 2015 is Presiding Bishop Joseph Ntombura. The church’s senior clergy accuse the leader of mishandling the church’s funds and investments, including church-owned operations, such as hospitals, a resort, a national university and various office buildings.

“He (Ntombura) has displayed total incompetence as a leader. The church has gone down to zero after he took over in 2013. We have institutions of high status,” former Bishop Paul Matumbi Muthuri told RNS in a telephone interview on March 14. “He has run down all these institutions.”

The Methodist Church in Kenya, established in 1862 by the British Methodist Church and made autonomous in 1967, has had a fairly stable history in the country until 2015 when, two years into his term, Ntombura changed the church’s constitution and established new rules.

“He established new rules that are strange to our tradition. So from 2015, the people have had bad leadership all along and they have been in court,” said Muthuri, who was fired as bishop by Ntombura.

Misheck Kobia Michubu, the steward of the Kawangware Circuit in Nairobi, told RNS the church and its institutions are in a precarious place.

“It is like we have lost direction. It is like the church is breaking into pieces,” said Michubu. “Every time the church members want to discuss these matters, (Ntombura) gets a court order.”

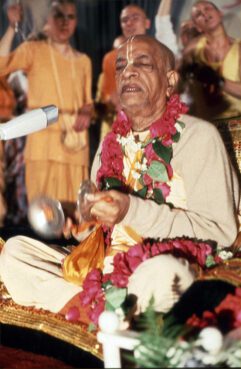

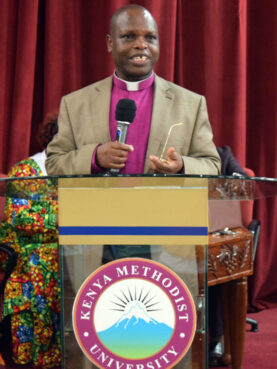

Presiding Bishop Joseph Ntombura speaks at a Kenya Methodist University event. Photo via social media

He pointed to the Kenya Methodist University as an example. During Ntombura’s tenure as presiding bishop, which also includes the role of university chancellor, the student population of the school has declined from 13,000 to less than 3,000, and five campuses have closed, according to Michubu.

“We have seen some items being auctioned. We hear there is a huge debt. We also hear the same regarding the church hospital in Maua (a town in Meru County). The problem has been a massive interference in the running of the institutions by the presiding bishop,” said Michubu.

He also registered concern about missions established by the Kenyan church in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and South Sudan, which had been running well, according to Michubu, but the current status of them is uncertain.

“They may be running, but very dismally,” he said.

Muthuri accuses Ntombura of defrocking more than 100 clerics, selling church properties and using the remaining ones as security to acquire loans.

Michubu agrees the clergy have borne the brunt of Ntombura’s administration, since those who dissent are not “stationed” or are moved from one station to another, some to as many as five in one month.

“He has been using stationing as a tool to punish those who don’t agree with him,” said the official.

Ntombura has not responded to telephone calls and RNS’ requests for comment, but in January he told Kenya’s Nation Newspaper that he is fighting corruption and that rogue clergy are attempting to block his efforts.

The Methodist Church in Kenya logo. Courtesy image

“The process of cleaning up the church affiliated institutions and restoring the dignity of the church, I have encountered a battalion of enemies. Corruption is fighting back,” he told the Nation on Jan. 19.

The bishop said he took over a church that had no money for mission work and was relying on loans to pay office rent. He also complained the official residence of the presiding bishop had no furniture when he moved in.

He said the church university was in a financial crisis and was borrowing money, while its official books showed a surplus. A forensic audit showed the institution was running on fake financial books, had unpaid statutory dues, loans and credits, according to Ntombura.

“We had to move with speed to restructure the loans and fix the management and save the university from the auctioneer’s hammer,” he told the daily.

Clerics and lay leaders say as a consequence of the infighting, the church’s membership has declined across the country, with people migrating to other churches. Some churches have been cutting links with Ntombura’s leadership, beginning with those in the coastal region, which formed a conference in 2019. In 2020, the Mt. Kenya region conference was established, and another in Nairobi is taking shape. These are partly autonomous and led by their own presidents.

“We are not splitting, but it is the same church which is decentralizing through regional conferences. We have had one conference in Nairobi, under one man or woman, but we feel the church has outgrown its establishment, and we cannot afford to have one center of power,” said Muthuri.