(RNS) — Gilad Kariv serves in Israel’s parliament, the Knesset, as a member of the opposition Labor Party.

He is also Israel’s first and only Reform rabbi serving as a legislator.

In this, he charts a pioneering path. A native of Israel who grew up in a secular Jewish home in Tel Aviv, Kariv embraced the Reform Jewish movement, which, when he was growing up — he is 49 — accounted for a sliver of Israeli Jews. (Israel’s polarized religious landscape is broadly made up of secular and Orthodox Jews.)

Kariv has advocated for greater religious pluralism in Israel and has worked to expand the Reform movement’s presence. It now has 54 congregations. (There are about 850 congregations in North America.)

He is also a lawyer and serves on the Knesset’s Constitution, Law and Justice Committee. That makes him privy to the negotiations over the right-wing coalition’s efforts to enact legislation that would sharply curtail the Supreme Court’s powers.

The proposed judicial overhaul has drawn massive opposition protests by Israelis who say it will destroy the country’s democratic foundations. The judicial overhaul has also tested relations with American Jews who, with some exceptions, have embraced Israel uncritically.

RNS spoke with Kariv, who returned to Israel on Sunday (March 19), about the portentous changes ahead in Israel and how he thinks American Jews ought to respond.

Knesset member Rabbi Gilad Kariv meets with the Finance Committee on May 3, 2021. Photo by Dani Shem-Tov, Knesset Spokesperson’s Office

The interview was edited for length and clarity.

You’re negotiating a compromise to the judicial overhaul bill. How’s that going?

I’m a member of the committee that deals with most of the legislation on the table. We are deeply frustrated with the way the government is pushing this legislation forward. We don’t identify a real desire to reach a compromise. The government and coalition are not responding positively — even to the suggestions of the president, Isaac Herzog. As long as the government insists on (passing) this legislation in a few weeks, we are mainly committed to battling this bad legislation.

How soon do you expect the Knesset will pass the legislation?

The government’s plan is quite clear. They want to complete the legislation around the nomination process of judges and around the constitutional authorities of the Supreme Court by the end of the winter session, which ends before Passover (April 5). We are deeply worried about future (legislation), too. We are placing a lot of pressure on the coalition and the government to at least wait until the next session that starts in May. The fact that they’re not willing to do this — to enable the Israeli society and political system to see if we can build a wider consensus — this, for us, is the main signal that they’re not serious when they talk about reaching a compromise. You can’t reach a compromise around such fundamental constitutional issues in two and a half weeks.

What do Knesset members think of the protests?

Israel has experienced significant waves of civil protests before. It’s a sign of democratic health. But the current protests are the largest we’ve ever experienced, and they’re totally decentralized. They are not led by the opposition parties. Politicians are not speaking from the main stage. The unions aren’t leading the demonstrations. There’s no specific group of NGOs. It’s a massive grassroots movement that brings Israelis to the streets.

We see young people, veterans, the former leaders and commanders of Israel’s security agencies: the Israel Defense Forces, the Mossad. They’re all there, saying this judiciary reform will harm Israel. You have leaders of the high tech industry talking about Israel’s economy. The CEOs of all the Israeli banks, the universities. You see a very deep understanding that this is a dramatic moment. Some of the more moderate right-wing politicians; some of the local mayors that come from the Likkud, they get it. They understand it’s not an ordinary civil protest.

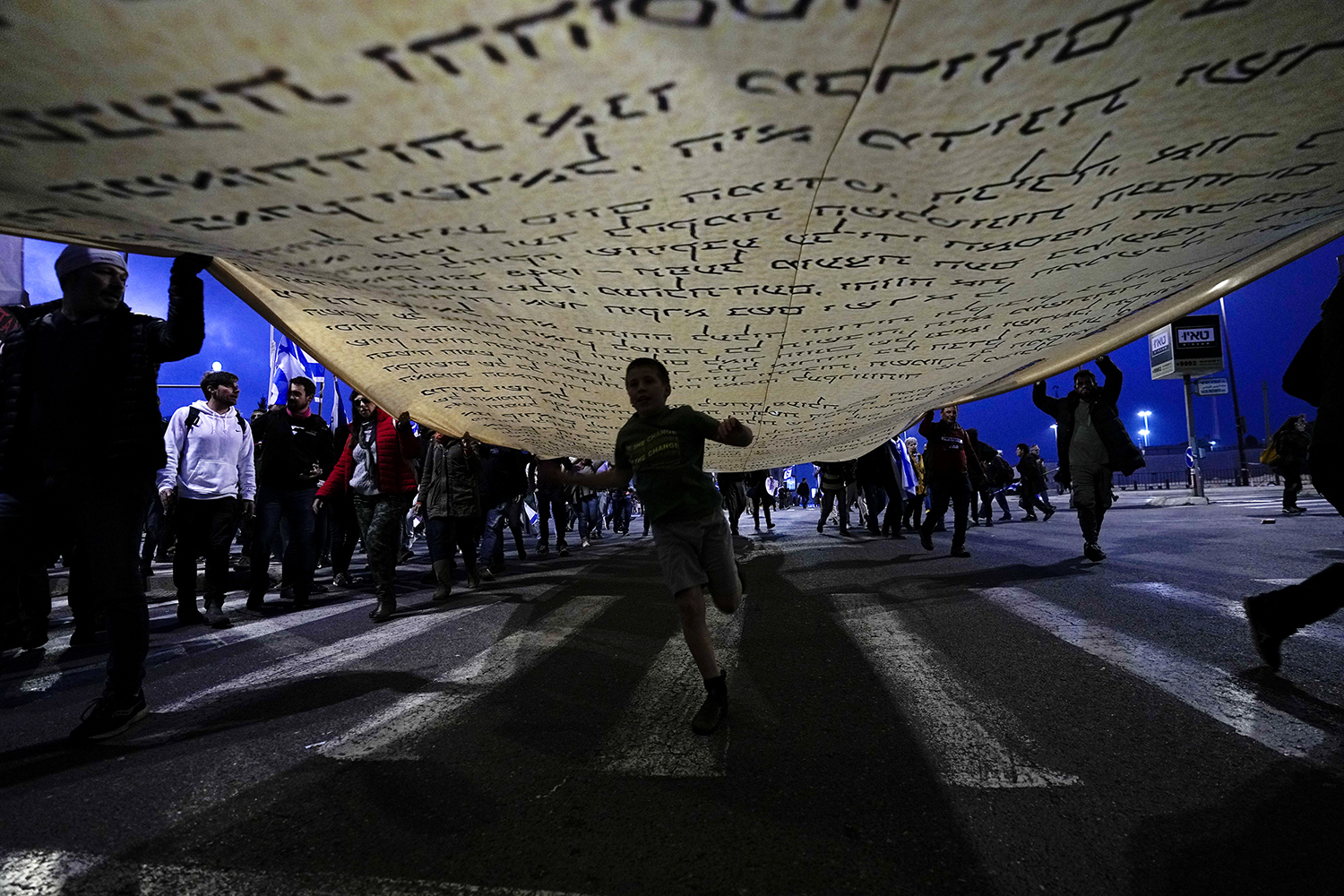

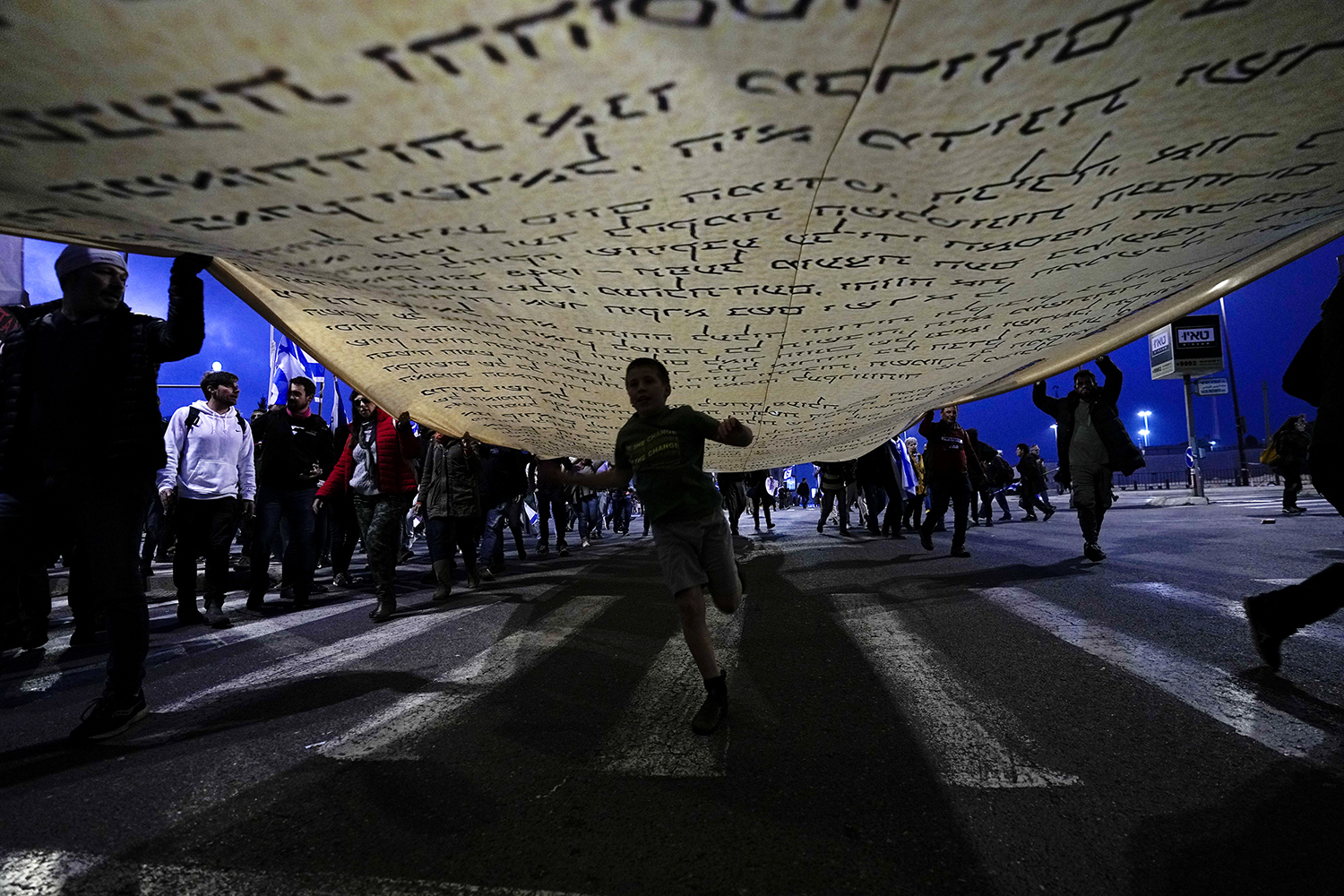

Protesters carry a large copy of the Israeli Declaration of Independence during a protest Feb. 20, 2023, near the Knesset, Israel’s parliament, in Jerusalem. Demonstrators oppose plans by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s new government to overhaul the judicial system. (AP Photo/Ohad Zwigenberg)

Unfortunately, most of them are not brave enough to say, ‘We need to slow down this process.’ The majority of the right-wing politicians are doing whatever they can to delegitimize the protests and to present those hundreds and thousands of citizens as people who don’t respect the outcome of the last elections, as people trying to undermine Israel’s national security, or as anarchists.

Is there any chance this government could fall?

I tend to believe it is very difficult for an Israeli government to face such a massive civil protest. It doesn’t mean this government will fall in a few weeks or months. They have the necessary political energy to keep going. But it is becoming clear the government will not be able to push all its policies forward because internal pressures are growing dramatically. Israel also has real risks to its national security. To face those security challenges, you can’t allow yourself such social and political frustrations.

If they continue with their extreme policies, it will be extremely difficult to overcome the protests. Foreign governments, including the American administration, are also disturbed. They understand there is a link between judicial reform and the desire among some elements in the coalition to create de-facto annexation in the West Bank or change the policies of the government toward the Palestinian Authority.

You’re the first and only Reform rabbi in the Knesset. What do people think of you?

There is a huge political debate in Israel between the non-Orthodox denominations and the Orthodox establishment that enjoys public funding and governmental authority in marriage and divorce. They identify me as someone who is trying to change the nature of synagogue and state relations in Israel. They see me, correctly, as someone who is struggling with deep, real, profound change in Israel’s attitudes toward non-Orthodox denominations.

The reason millions of Israeli Jews want nothing to do with Judaism is because they identify Judaism with the corrupt and aggressive Orthodox monopoly. At the same time, growing circles of Israelis understand the deep connection between Israeli Judaism and Israeli democracy. People understand there is a reason why the Orthodox parties in Israel fully back this judicial reform and why they’re deeply interested in weakening the constitutional authority of the Supreme Court. They want to make sure Israeli democracy is limited when it comes to freedom of religion. They don’t want Israeli Judaism to be diverse and pluralistic.

Knesset member Rabbi Gilad Kariv on July 1, 2021. Photo by Noam Moshkowitz, Knesset Spokesperson’s Office

Reform Judaism, which is dominant in the U.S., is still very small in Israel. How did you become a Reform Jew?

Reform and Conservative Judaism didn’t play major roles in building the state of Israel or of maintaining and cultivating it. Yet there are important exceptions. The Hebrew University was established by a Reform Rabbi (Judah Leon Magnes). The women of Hadassah, who established the foundations of Israel’s welfare system, were Conservative Jews. Yet, I agree: Reform Judaism was a marginal player in the religious landscape in Israel.

Zionism is not a religious movement. But it is a cultural movement in addition to being a national and political movement. It revived the Hebrew language and the Jewish calendar and restored the Jewish holidays’ agricultural and land-based character.

My grandparents grew up in Orthodox families. They all left the Orthodox lifestyle and adopted a secular lifestyle. But they were deeply involved in the national enterprise of building a nation. They didn’t need a synagogue experience. They had a very rich Jewish life without worship, without spiritual Jewish experiences. For my generation, it’s becoming clear that unless we invest in our Jewish identity — unless we revive different elements of Judaism that were less relevant to the founding generations — it will be very difficult to maintain a rich and fulfilling Jewish identity.

As a teenager I wanted something more. My Judaism was deep, but with no spiritual expression. This is a development of the last two or three decades. There is a growing native Israeli audience that is interested in an egalitarian, inclusive, open-minded, pluralistic, spiritual and communal Jewish experience. They’re not willing to give up their liberal values when they celebrate their Judaism.

A new Gallup poll shows that U.S. Democrats sympathize more with Palestinians than with Israel. How do you respond to that?

I strongly believe the future of the state of Israel as Jewish and democratic depends on our ability to find a solution to this terrible national and religious conflict.

I want American Jews to help us reach a political solution to this conflict. Having said that, we have a big challenge. The most important insurance policy we have to cultivate the sympathy of Americans toward Israel is the concept of shared values. Israel must insist on keeping itself as part of the democratic liberal world.

There aren’t any easy calls in regard to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. We need to cultivate our commitment to promote a political solution. The future of Israel relies not only on its ability to guard itself from its enemies but on the democratic wellbeing of our state. If you love Israel you must help us guard its democratic nature.

I’m calling on American rabbis to use the pulpit. American legislators, too, can tell their friends, ‘It doesn’t look good.’ That’s what you do when you love someone and you feel they’re taking the wrong direction. It’s an expression of love, not detachment. It’s a critical moment. We expect our brothers and sisters in North America to help protect Israel’s democracy.

.jpg?ext=.jpg) Energoatom President Petro Kotin and Rolls-Royce SMR's Sophie Macfarlane-Smith signing the MoU (Image: Energoatom)

Energoatom President Petro Kotin and Rolls-Royce SMR's Sophie Macfarlane-Smith signing the MoU (Image: Energoatom).jpg) From left to right: Fortum Technical Director Olli Kymäläinen, Rolls -Royce SMR Head of Business Development, Nordics Tuomo Huttunen, Fortum Head of New Build Feasibility Study Laurent Leveugle, and Rolls-Royce SMR Head of Customer Engagement Sophie Macfarlane-Smith (Image: Rolls-Royce SMR)

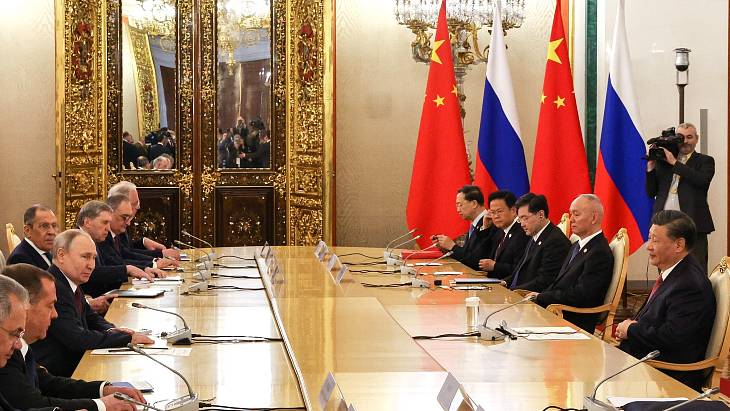

From left to right: Fortum Technical Director Olli Kymäläinen, Rolls -Royce SMR Head of Business Development, Nordics Tuomo Huttunen, Fortum Head of New Build Feasibility Study Laurent Leveugle, and Rolls-Royce SMR Head of Customer Engagement Sophie Macfarlane-Smith (Image: Rolls-Royce SMR) The two countries agreed to deepen cooperation in a wide range of areas (Image: www.kremlin.ru)

The two countries agreed to deepen cooperation in a wide range of areas (Image: www.kremlin.ru).jpg?ext=.jpg) A cutaway of a plant based on the BWRX-300 (Image: GEH)

A cutaway of a plant based on the BWRX-300 (Image: GEH)