The Guardian

Sun, 2 April 2023

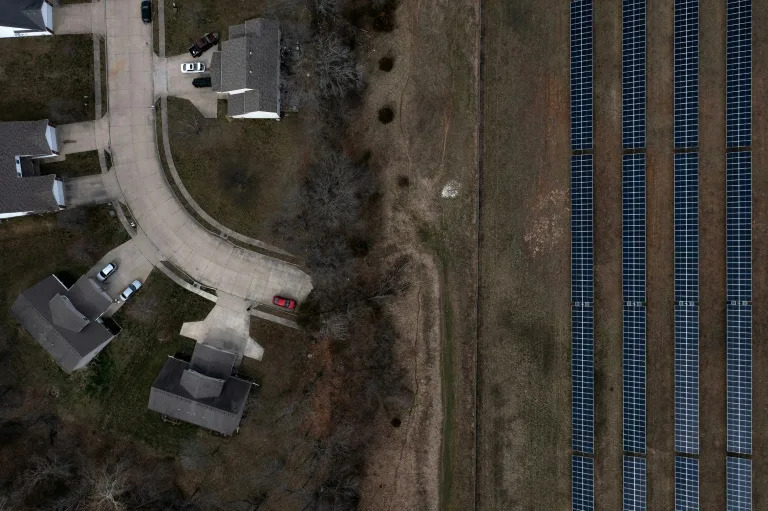

Photograph: Christopher Jones/Alamy

My career in textiles from the 1970s to the 1990s took me many times to the mills of West Yorkshire and Lancashire. Being fascinated with old buildings, I marvelled at the architectural glories of the likes of Salts Mill, the Black Dyke Mills, Lister Mill in Bradford and many smaller, though equally impressive edifices. Never once did it cross my mind that these dark satanic mills were not only products of Yorkshire and Lancashire entrepreneurs, but built on the back of a vast network of slaves and slave-owning people who amassed the wealth of Great Britain in the industrial revolution.

Is it too patronising to congratulate the Guardian for the recognition of its involvement in this, with the founders of the paper being patrons and owners of companies involved?

David Olusoga’s wonderful research and work on this (Slavery and the Guardian: the ties that bind us, 28 March) should make us all think about how we have enjoyed the fruits of these industries. MULTIMEDIA PRESENTATION

As a white, middle-class, elderly woman, I take my hat off to them and hope that we can all begin to see ourselves in a new light and set about realising where the privileges have come from that built the successful towns and cities in our country, and which shaped the lives of people of my background.

Sue Neave

Cleethorpes, North East Lincolnshire

• David Olusoga lifts the veil on the relations between slavery and the growth of Britain’s cotton industry. His article, revealing as it is of blind spots in official and folk histories, still misses a vital part of the narrative – how Britain came to command the global cotton industry through the deliberate destruction of the textile industry of India, the hitherto dominant producer of finished cottons.

Mechanisation of cotton production in British factories depended on securing a mass Indian market through the dispossession and starvation of the Bengali handloom weavers, a process that was then duplicated (as documented by Edward Thompson in The Making of the English Working Class) in the metropolis.

Empire was a system in which slavery was central, as was the transformation of the colonies into sources for the extraction of raw materials to feed the industries of the coloniser.

Chris Sinha

Cringleford, Norfolk

• A thousand thanks – what a tremendous emotional shakeup the articles in your Cotton Capital series gave me. Above all, the list of names of those slaves whom your journalists and investigators successfully identified. Behind each name is a tragic story that is impossible to understand from our position of comfort and security that we enjoy today. I would especially like to thank David Olusoga for his remarkable article.

We can never atone enough for the wrongs that our English ancestors did, and I am so grateful that you have decided to at least acknowledge the wrongs and make every effort to provide opportunities for others to find some sort of justice.

David Hesketh

Castanet Tolosan, France

• Here is my suggestion for a concrete, meaningful way that the Guardian can begin to pay reparations for its past ties to slavery: set up a fund to pay for schoolchildren in Ghana to visit Cape Coast Castle, one of the main slave-trading forts, for free. When I visited it a few years ago to give a lecture on the history of the slave trade, I was shocked to learn that Ghanaian children are charged to enter the castle, making this important historical site off-limits to many of them. This history is their history; they must learn about this past, and the Guardian can help them to do it.

Michelle Faubert

University of Manitoba, Canada

As a white, middle-class, elderly woman, I take my hat off to them and hope that we can all begin to see ourselves in a new light and set about realising where the privileges have come from that built the successful towns and cities in our country, and which shaped the lives of people of my background.

Sue Neave

Cleethorpes, North East Lincolnshire

• David Olusoga lifts the veil on the relations between slavery and the growth of Britain’s cotton industry. His article, revealing as it is of blind spots in official and folk histories, still misses a vital part of the narrative – how Britain came to command the global cotton industry through the deliberate destruction of the textile industry of India, the hitherto dominant producer of finished cottons.

Mechanisation of cotton production in British factories depended on securing a mass Indian market through the dispossession and starvation of the Bengali handloom weavers, a process that was then duplicated (as documented by Edward Thompson in The Making of the English Working Class) in the metropolis.

Empire was a system in which slavery was central, as was the transformation of the colonies into sources for the extraction of raw materials to feed the industries of the coloniser.

Chris Sinha

Cringleford, Norfolk

• A thousand thanks – what a tremendous emotional shakeup the articles in your Cotton Capital series gave me. Above all, the list of names of those slaves whom your journalists and investigators successfully identified. Behind each name is a tragic story that is impossible to understand from our position of comfort and security that we enjoy today. I would especially like to thank David Olusoga for his remarkable article.

We can never atone enough for the wrongs that our English ancestors did, and I am so grateful that you have decided to at least acknowledge the wrongs and make every effort to provide opportunities for others to find some sort of justice.

David Hesketh

Castanet Tolosan, France

• Here is my suggestion for a concrete, meaningful way that the Guardian can begin to pay reparations for its past ties to slavery: set up a fund to pay for schoolchildren in Ghana to visit Cape Coast Castle, one of the main slave-trading forts, for free. When I visited it a few years ago to give a lecture on the history of the slave trade, I was shocked to learn that Ghanaian children are charged to enter the castle, making this important historical site off-limits to many of them. This history is their history; they must learn about this past, and the Guardian can help them to do it.

Michelle Faubert

University of Manitoba, Canada