ISIS mines kill six truffle hunters in Syria

It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way (K.Marx, Letter to F.Engels on the Indian Mutiny)

ISIS mines kill six truffle hunters in Syria

Africa: Why Instituting Longer Paternity Leave in Africa Is Not Simple

The push for longer paternity leave speaks to how kin networks locally and around Africa have broken down in the demographic, sociological and economic changes that characterise modern society

But given the level of development in much of Africa, instituting paternity leave may not be quite so simple. Before we see why, however, let us start from the beginning.

The kin networks are extended family institutions in many African communities that provide a social security system, including for child care. You might still find such networks in rural areas.

When a child is born, for example, members of the extended family such as mothers-in-law or sisters-in-law and even neighbours assist in caring for the newborn baby and the nursing mother.

They share the emotional and physical burden that a nursing mother goes through during the early period of childrearing.

This however doesn't tend to work very well nowadays, especially in urban settings. This is not only because many in the towns are disconnected from their extended families but the demands of employment mean that people are tied to their work in the formal and informal sectors of the economy.

But the real issue is unpaid work, where mothers, including working mothers, for example, are left to run the home and take care of the children including the newborns, often with little support from the fathers.

Our governments are, of course, seized of this fact. Except that while maternity leave for women is up to 12 weeks or more, paternity leave for new fathers is between one and five days in the vast majority of countries in the continent.

Those with longer include Zambia with seven days paternity leave, and ten days in Cameroon, South Africa and Seychelles. In Burkina Faso, the leave is 20 days.

In the East African Community, the leave is three days in Tanzania, two days in DR Congo and four days each in Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi. In Kenya and South Sudan, the leave is two weeks.

Aside from the benefits the advocates of longer paternity leave cite such as fathers supporting both mother and infant at their most vulnerable, studies show the provision of paternity leave can improve women's chances in paid employment.

One example of this is where it may change employer attitudes. For instance, if a particular position requires investment in job training, employers have been known to discriminate against women, anticipating frequent absence due to childbirth and child-rearing activities.

However, if paternity leave allows men to spend more time outside employment, assuming considerable uptake of paternity leave, this may limit discrimination against women.

If there are clear benefits, what are the barriers?

To take the case of Rwanda, men advocates cite, among others, maternal "gate-keeping" as an important barrier to the involvement of men in caregiving activities.

Another is the limited policy and legislative environment and the primacy of a patriarchal culture that dictates the division of labour between mothers and fathers.

In concrete terms, to quote one often-cited study by Action Aid Rwanda, women in rural areas spend up to 7 hours a day on unpaid care work while men do around 1 to 3 hours a day.

The lopsidedness of this division of labour clearly needs to be addressed.

However, it may seem that paternity leave as a possible solution is not quite so simple.

Take the example of Uganda, as described in an analysis under the global policy forum OECD. The four days of paternity leave, as per Ugandan law, apply to the formal sector which employs less than 8 per cent of the working-age population. This in effect means it covers only a small population of employed fathers.

Furthermore, and this is not just in Uganda but in countries in the region and across Africa, there are no institutions to enforce the leave.

The other concern similar to that expressed by the Rwandan advocates, the four days are too short to lead to care equality.

In Uganda, however, most men in the formal sector rarely use them.

Also, as in Rwanda, there is limited awareness of the need for and entitlement to paternity leave.

The Uganda situation is reflective of much of Africa. Thus the analysis concludes that paternity leave for economies with high informality and institutional gaps in enforcement is unrealistic.

Therefore, African governments, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa, should invest in the supply side of gender-sensitive infrastructure to ease the care work burden.

Such infrastructure includes early childhood development centres, play parks, public transport with priority areas for mothers and fathers with children and breastfeeding centres.

These should be affordable, accessible and non-discriminatory. In the long term, they might do more for gender parity than paternity leave.

Read the original article on New Times.

My family survived the Deir Yassin massacre. 75 years later, we still demand justice.

The terraced stone homes of Deir Yassin stand seemingly undisturbed behind the locked gates of the Kfar Shaul psychiatric hospital compound. Virtually suspended in time and inaccessible to the public, it’s a fitting metaphor for the sustained concealment of the atrocities committed there.

Seventy-five years ago today, April 9, the quiet stonecutter village of Deir Yassin became the site of the massacre that continues to reverberate with chilling significance for the Palestinian people.

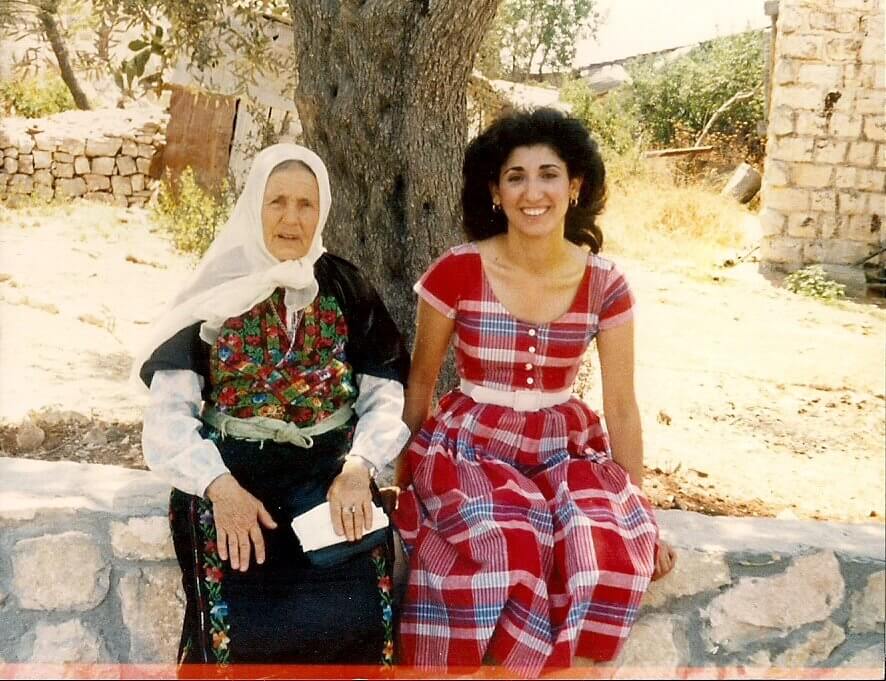

On my first visit to Deir Yassin in 1998 — on the massacre’s 50th anniversary — I walked down its quarry-studded pathways and admired the flowering prickly cactus plants leading to my grandmother’s family home. Her words still echo in my head, each syllable striking my mind like the knives that spilled the blood of the villagers.

“Never forget what happened here. Inscribe it in stone. Engrave it in your heart forever,” she had pleaded to me, tapping her fingers against her chest.

For many Nakba survivors, the most minute details of the atrocities they witnessed remain fresh in their memories as though they happened yesterday. My grandmother recalled the stench of bloodied corpses, and the gruesome sight of her grandfather’s contorted, bullet-riddled body strewn on their home’s front steps.

PHOTO OF THE AUTHOR’S GRANDMOTHER, FATIMA ASAD, SEEING HER FAMILY HOME IN DEIR YASSIN BEHIND THE FENCE. EVEN THOUGH IT WASN’T THE FIRST TIME SHE WAS SEEING HER HOME AFTER THE MASSACRE, THIS PHOTO CAPTURED THE SHOCK AND HEARTACHE WRITTEN ON HER FACE UPON SEEING OCCUPANTS ON THE BALCONY OF HER HOME. (PHOTO COURTESY OF DINA ELMUTI)

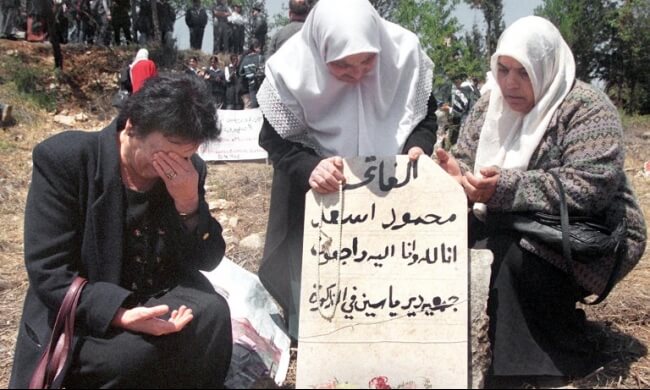

PHOTO OF THE AUTHOR’S GRANDMOTHER, FATIMA ASAD, SEEING HER FAMILY HOME IN DEIR YASSIN BEHIND THE FENCE. EVEN THOUGH IT WASN’T THE FIRST TIME SHE WAS SEEING HER HOME AFTER THE MASSACRE, THIS PHOTO CAPTURED THE SHOCK AND HEARTACHE WRITTEN ON HER FACE UPON SEEING OCCUPANTS ON THE BALCONY OF HER HOME. (PHOTO COURTESY OF DINA ELMUTI) PHOTO OF THE AUTHOR’S LAST VISIT TO DEIR YASSIN WITH HER LATE GRANDMOTHER, FATIMA ASAD, WHO IS POINTING TO HER FAMILY HOME FROM BEHIND A FENCE. THEY WERE NOT ALLOWED ACCESS INTO THE VILLAGE TO SEE IT UP CLOSE. PHOTO TAKEN IN 2015. (PHOTO COURTESY OF DINA ELMUTI)

PHOTO OF THE AUTHOR’S LAST VISIT TO DEIR YASSIN WITH HER LATE GRANDMOTHER, FATIMA ASAD, WHO IS POINTING TO HER FAMILY HOME FROM BEHIND A FENCE. THEY WERE NOT ALLOWED ACCESS INTO THE VILLAGE TO SEE IT UP CLOSE. PHOTO TAKEN IN 2015. (PHOTO COURTESY OF DINA ELMUTI)The trauma that our elders experienced during the Nakba inhabits our beings and becomes a part of us. Generations later, it lances through our bodies and leaves a soul wound. The intergenerational transmission of trauma in the grandchildren of Nakba survivors is a wordless story.

No words of any human language can ever fully describe the atrocities committed in Deir Yassin, or any of Israel’s successive massacres. It’s a unique torment that flashes through our veins with severity, a waking nightmare that settles on our chests, grips our throats, and opens our mouths to soundless cries.

When my grandmother died, I felt the immense grief of losing my first storyteller. It became an urgent duty to keep the Nakba narratives alive after the remaining survivors die, and the detailed horrors fade from living memory.

My first visit to Deir Yassin drove me to explore the historical memory surrounding the Nakba, and has continued to underscore my entire life as a trauma social worker and storyteller.

On the morning of April 9, 1948, the village of Deir Yassin felt the breath of death. By mid-afternoon, the streets were a bloody slaughterhouse and graveyard of unspeakable horrors. Zionist forces beat, stabbed, lined up and executed villagers — firing squad-style. Their violence and rage expanded beyond the execution of captive villagers. Surviving villagers, like my great uncle Dawud, who was 17 years-old at the time of the massacre, affirmed that Zionist forces terrorized, robbed, raped, brutalized, and blasted villagers with hand grenades. They crushed, bayoneted, and eviscerated the abdomens of pregnant women while they were still alive, and maimed and beheaded children in front of their own parents.

Everyone, from the unborn and nursing infants to the elderly, was a target for elimination.

Nearly two-thirds of the massacred consisted of children, women, and elderly men above the age of 60. Zionist thugs hauled several bodies to the village stone quarry where they buried and burned them. Unnerved by the barbarities, they ate with gusto next to charred corpses.

BULLET-PIERCED CACTUS PLANTS OUTSIDE DEIR YASSIN (PHOTO COURTESY OF DINA ELMUTI)

BULLET-PIERCED CACTUS PLANTS OUTSIDE DEIR YASSIN (PHOTO COURTESY OF DINA ELMUTI)

The death toll of the massacre fell between 110 and 140 villagers, though Irgun commanders exaggerated the toll to 254 to escalate the terror and trigger the mass expulsion of Palestinians from neighboring towns and villages.

Today, Deir Yassin serves as the DNA of our current Nakba, remaining a haunting emblem of erasure and the ongoing systematic dispossession and forced displacement of Palestinians. Since then, the denialism and propagated myths at the core of the Zionist ideology have allowed for the state-sanctioned violence committed against Palestinians.

The deliberate destruction of memory is intrinsic to the genocidal process, but it’s impossible to forget the unforgettable. Or something that has never actually ended. The Nakba did not begin or end in 1948. It remains an ongoing catastrophe, trauma upon trauma compounded.

When it comes to forgetting such catastrophes, one borders on immorality, cruelty, or the reprehensible. To deny the suffering of victims is to deny the facts, history, and memory itself. For anyone in the world, this response would approach the incomprehensible and the unthinkable.

For everyone except the Palestinian people.

Forgetting, or rather denying, that massacres ever occurred has been reprehensibly common in the discourse surrounding the Nakba. References to the memory of survivors are often met with defiance and denial, their testimonies fraught with contention and controversy. These testimonies, however, continue to disrupt a discourse of veiled cruelty, enabling the enduring struggle against the imposition of silence and forgetting.

Memories that threaten and shatter the integrity of a state are difficult to reconcile with its present trajectory and image, which is why Zionists continue to defame and label everything as antisemitic. Zionists portray themselves as the victims, claiming their suffering and existential threat through deliberate acts of memory manipulation and willful distortion, thereby reducing their own culpability.

This is a psychic defense or psychological pathology. The psychiatric hospital expanded all over the blood and bones of family homes in Deir Yassin in itself symbolizes a nation’s suppressed subconscious past of denial. A nation reborn from the ashes of the Palestinian people.

The fire was extinguished from Deir Yassin 75 years ago, leaving in its wake a charred impression, the stains of which no amount of cleansing or denial could ever eliminate. The scale of the import of the systematic assaults committed by Zionists remains largely unrecognized, and generations of the architects that planned the Nakba and the butchers carried it out continue to go to their graves without repentance.

But the Palestinian people are not desperate for a semblance of recognition or fake remorse. Our memories, narratives, and lives exist. They have always existed. The onus to protect and preserve our memories and collective narrative, in the face of every attempt to erase them, will remain ours to carry.

We will continue to shatter the façade of deliberate distortions and disrupt the arrogant silence surrounding the Nakba. We will continue to resist, narrate, and prevent its memory from calcifying into the erased and forgotten.

Like the bullet-riddled cactus plants that bear the scars of Deir Yassin – blooming out of carnage and destruction – we will remain a thorn in the side of the occupation. We will continue to name the victims and tell the stories of those who struggle for their lives and dignity with determination, transmuting trauma into steadfastness.

We inherited the duty to never forget what happened, to inscribe it in our memories forever.

By: Dina Elmuti

Source: Mondoweiss