April 23, 2023

This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis. It was originally published at The Conversation.

The ghost of the Confederacy hangs heavily over the Tennessee Legislature.

Justin Jones, one of two Black members expelled from the state’s House of Representatives in April 2023, had run afoul of House leadership before. In 2019, as a private citizen, he was arrested following his actions in protesting a bust in the state capitol honoring Nathan Bedford Forrest, a Confederate general and later Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan.

While the expulsion of Jones and his colleague, Justin J. Pearson, riveted the nation’s attention, a curious and related event in the Legislature’s other branch, the Tennessee Senate, passed nearly unnoticed.

On Feb. 3, 2023, two state senators issued a formal proclamation commemorating April 2023 as and encouraging “all Tennesseans to increase their knowledge of this momentous era in the history of this State.”

One of the signers is Senate Speaker Randy McNally, who is also the state’s lieutenant governor; the other is Sen. Mark Pody from Lebanon. Though not considered in legislative session and not listed on the Legislature’s website, the proclamation holds an official stature: It was issued on Senate stationery and stamped with the Tennessee state seal.

The proclamation’s wording closely follows that of a proclamation issued by Virginia’s Gov. Robert McDonnell in April 2010, with one striking exception. McDonnell’s proclamation in final form included a paragraph, inserted after protests to an earlier version, stating “that it is important for all Virginians to understand that the institution of slavery led to this war.”

The Tennessee proclamation, which includes eight introductory clauses celebrating “the cause of Southern liberty,” says nothing of slavery at all. Rather, it declares that Confederates conducted “a four-year heroic struggle for states’ rights, individual freedom, local government control, and a determined struggle for deeply held beliefs.”

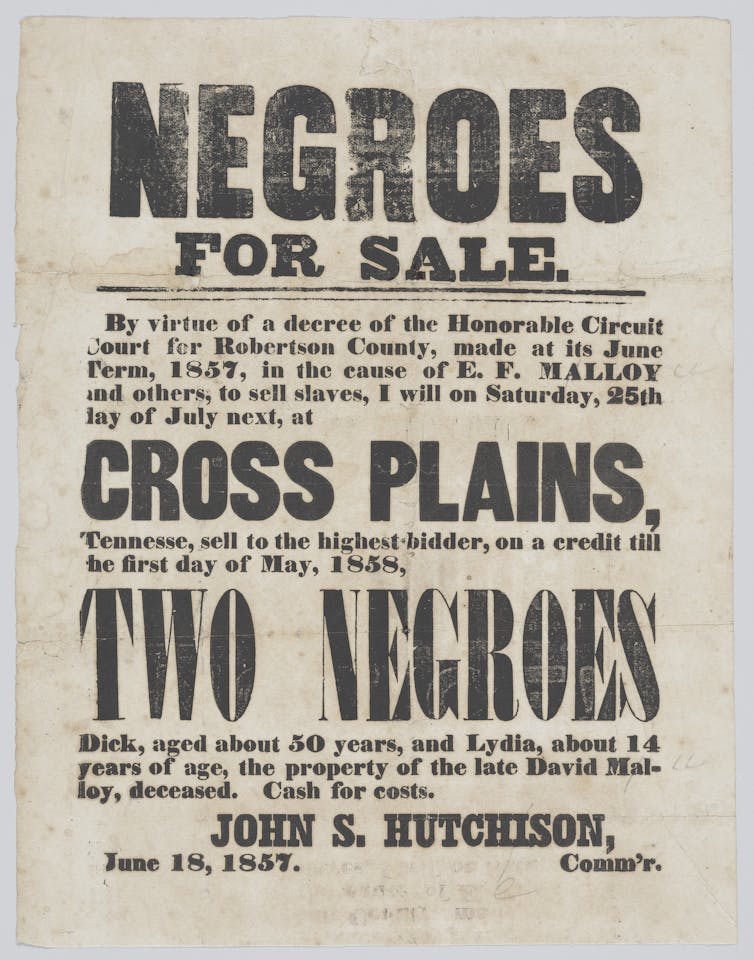

As we historians of the Civil War have tirelessly pointed out, the documentary record speaks clearly of the motive behind that “heroic struggle.”

Both official proceedings and private utterances prove abundantly that there was only one reason to secede from the United States and create a new Confederacy. That was to safeguard racial slavery from the threat posed by the election of an antislavery Northerner, Abraham Lincoln, as president of the United States.

Tennessee seceded later than other states, after the Confederate firing on Fort Sumter. Lincoln’s responding call for troops made plain that there would be a war and that Tennessee, like other fence-sitting Upper South states, would have to choose sides.

The record of the state’s reasons is easy to find, and would have been available to the authors of the recent proclamation. In 2021, the University of Tennessee Press published “Tennessee Secedes: A Documentary History.” It shows that in Tennessee, as elsewhere, the protection of slavery was the sole motive for secession.

In 1861, Gov. Isham Harris convened the state’s Legislature with a message denouncing the North’s “systematic, wanton, and long continued agitation of the slavery question,” crowned by the insulting election of a president who “asserted the equality of the black with the white race.”

Harris went on:

“To evade the issue thus forced upon us at this time, without the fullest security for our rights, is, in my opinion, fatal to the institution of slavery forever. The time has arrived when the people of the South must prepare either to abandon or to fortify and maintain it. Abandon it, we cannot, interwoven as it is with our wealth, prosperity and domestic happiness.”

In all the deliberations that followed, no cause or grievance but slavery was mentioned.

Yet these basic facts go unacknowledged in a proclamation that boldly declares that knowledge of Confederate history is “vital to understanding who we are and what we are.”

Other omissions in the proclamation are equally curious.

Tennessee’s role in the Confederacy was uniquely conflicted. Thousands of citizens, especially in mountainous East Tennessee, opposed secession. Ignoring “local government control,” the state suppressed their dissent by force.

Some 50,000 Tennesseans, white and Black, spurned the Confederacy and fought for the United States – more than from any other Confederate state. The proclamation silently erases not only their struggle and sacrifice but their very existence.

‘Be not deceived by names’

Whether the Confederacy should be celebrated or condemned depends inescapably on point of view.

The proclamation casts the Confederacy in the mode of the American Revolution. The picture it paints is of a noble, if unsuccessful, attempt to erect a new self-governing independent nation – ignoring the fact that the institution of human slavery was at its center, as the Confederate constitution made clear.

Yet from another perspective, the Confederacy was nothing more than an armed mass rebellion against a legitimately elected government.

It was, ironically, a famous Tennessean, President Andrew Jackson, who had warned would-be seceders in an official proclamation in 1832: “Be not deceived by names. Disunion by armed force is treason. Are you really ready to incur its guilt?”

Lincoln labeled the Confederacy an “insurrection” within the United States itself, which the government and loyal citizens had not only a right but a duty to put down.

In words that echo today, Lincoln also observed that if the United States won its battle against forcible dismemberment, “it will then have been proved that, among free men, there can be no successful appeal from the ballot to the bullet; and that they who take such appeal are sure to lose their case, and pay the cost.”

Celebrating insurrection

The old adage that the victors write history is true at least to this extent. Generally the American Revolutionaries are deemed patriot heroes rather than rebels and traitors because they won their war, and because the course of subsequent history appears to have vindicated their cause.

Yet many Confederate acolytes, the proclamation’s sponsors among them, seem to have difficulty confronting what the Confederacy actually stood for. Hence, citizens serving in government – who upon entering their offices take a solemn oath to uphold and defend the United States Constitution and begin their daily sessions by pledging allegiance to “one Nation indivisible” – chose to officially exalt a failed attempt to overthrow that Constitution and dismember the nation that it bound together.

Under a statute enacted in 2021, Tennessee public school teachers are barred from using instructional materials “promoting or advocating the violent overthrow of the United States government.”

No such prohibition applies to state legislators.

Daniel Feller is an Emeritus Professor of History at University of Tennessee

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.