By Remi BANET

That's enough to make the 18-year-old back the Turkish president's main rival when he votes for the first time on May 14.

"I am tired of getting up every day and thinking about politics," said Ferli, referring to the tumult of Erdogan's 20-year rule.

"When President Erdogan is gone, young people will be able to focus on their exams and to speak freely."

Like Ferli, around 5.2 million Turks who reached voting age since Erdogan came to power in 2003 -- eight percent of the electorate -- will have their first say on election day.

The 69-year-old president's chief opponent, 74-year-old former civil servant Kemal Kilicdaroglu, is banking on students such as Ferli.

"It is through you that spring will come," the grandfatherly leader of Turkey's main secular party told a youth rally in Ankara.

Opinion polls suggest that Kilicdaroglu has reason to be optimistic.

One survey showed only 20 percent of Turks in the 18-25 age bracket ready to vote for Erdogan and his Islamic-rooted party in the presidential and parliamentary polls.

Both past Turkey's retirement age, Erdogan and Kilicdaroglu have been trying to seduce Gen Z voters with pledges to abolish a tax on mobile phone purchases and free internet packages.

Adding to Erdogan's problems, a third candidate, 58-year-old secular nationalist Muharrem Ince, is posing as a more fresh-faced alternative.

"The Erdogan vote is lower among young people," said Erman Bakirci, a researcher at the Konda polling institute.

"First-time voters are more modern and less religious than the average voter, and more than half are dissatisfied with the life they lead."

In Kasimpasa, a working-class Istanbul district where Erdogan played street football growing up, some have no fear of speaking out against their native son.

"Erdogan must go! All my neighbours will vote for him, but not me," Gokhan Celik, a 19-year-old in a green tracksuit, declared under two flags emblazoned with the president's face.

Firat Yurdayigit, 21, a textile worker, criticised Erdogan for building a third airport for Istanbul "instead of taking care of people".

"I will vote for Muharrem Ince," Yurdayigit said. "But no matter who is elected, anyone is better than Erdogan."

His friend Bilal Buyukler, 24, tried to defend the Turkish leader.

"I can't find work because of the Syrian refugees," said Buyukler, blaming his unemployment on the 3.7 million people who fled war on Turkey's southern border to big cities such as Istanbul.

"I can't get married -- it's too expensive," he said. "But I don't see any alternative.

"I can't vote for Kilicdaroglu because of religion. He walked on a prayer rug with his shoes!" he exclaimed, pointing to a campaign faux pas by the opposition leader highlighted by pro-government media and Erdogan.

Kilicdaroglu has taken pains to dispel the staunchly secular image of his CHP party, a constant worry for socially conservative voters who found a home in Erdogan's AK Party.

Last year, Kilicdaroglu proposed a law guaranteeing women's right to wear headscarves, trying to peel away voters won over by Erdogan's unshackling of religious restrictions.

"Mr Kemal will never let you lose your gains," Kilicdaroglu said in a video message aimed at conservative women.

His six-party alliance also includes three conservative Islamic groups, which Seda Demiralp, an associate professor at Istanbul's Isik University, called "a message of reconciliation intended for the religious electorate".

Sevgi, 20, lives in Eyup, one of Istanbul's most conservative districts.

She will vote on May 14 but does not want to "mix politics and religion".

"Erdogan is the main obstacle to my dreams," said the young woman, who is working to raise money to pay for design school.

Her boyfriend interrupted, listing some of Erdogan's achievements.

But Sevgi shook her head. "Even if he was a good president, he shouldn't be able to rule for so long," she said.

© Agence France-Presse

By Dmitry ZAKS

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan dives Sunday into the final two-week stretch before a momentous election that has turned into a referendum on his two decades of divisive but transformative rule.

The 69-year-old leader looked fighting fit as he strutted back on stage after a three-day illness and tossed flowers to rapturous crowds at an Istanbul aviation fest on Saturday.

It was the perfect venue for reminding Turks of all they had gained since his Islamic-rooted party ended years of secular rule and launched an era of economic revival and military might.

He was flanked by the president of Azerbaijan and the Ankara-backed premier of Libya -- two countries where drones built by his son-in-law's company helped swing the outcome of wars.

Istanbul itself has become a modern and chaotic megalopolis that has nearly doubled in size since Erdogan came to power in 2003.

But hiding beneath the surface are a more recent economic crisis and fierce social divisions that have given the May 14 parliamentary and presidential polls a powder keg feel.

The nation of 85 million appears as splintered as ever about whether Erdogan has done more harm than good in the only Muslim-majority country of the NATO defence bloc.

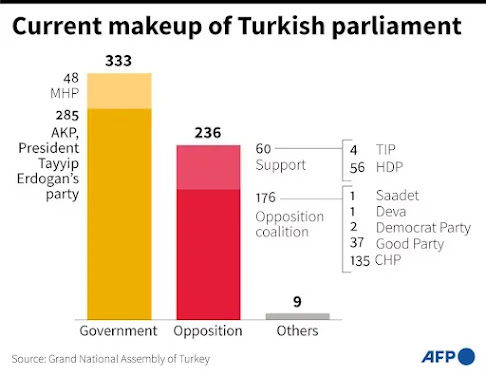

Polls show him running neck-and-neck against secular opposition leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu and his alliance of six disparate parties.

The entry of two minor candidates means that Erdogan and Kilicdaroglu will likely face each other again in a runoff on May 28.

But some of Erdogan's more hawkish ministers are sounding warnings about Washington leading Western efforts to undermine Turkey's might through the polls.

Interior Minister Suleyman Soylu referred Friday to US President Joe Biden's 2019 suggestion that Washington should embolden the opposition "to take on and defeat Erdogan".

"July 15 was their actual coup attempt," Soylu said of a failed 2016 military putsch that Erdogan blamed on a US-based Muslim preacher.

"And May 14 is their political coup attempt."

Turkey is now filled with hospitals and interconnected with airports and highways that stimulate trade and give the vast country a more inclusive feel.

He empowered conservative women by enabling them to stay veiled in school and in civil service -- a right that did not exist in the secular state created from the Ottoman Empire's ashes in 1923.

And he won early support from Turkey's long-repressed Kurdish minority by seeking a political solution to their armed struggle for an independent state that has claimed tens of thousands of lives.

But his equally passionate detractors point to a more authoritarian streak that emerged with the violent clampdown on protests in 2013 -- and became even more apparent with sweeping purges he unleashed after the failed 2016 coup attempt.

Erdogan turned against the Kurds and jailed or stripped tens of thousands of people of their state jobs on oblique "terror" charges that sent chills through Turkish society.

His penchant for campaigning and gift for public speaking enabled him to keep winning at the polls.

But the current vote is turning into his toughest because of a huge economic crisis that erupted in late 2021.

Erdogan's biggest problems started when he decided to defy the rules of economics by slashing interest rates to fight inflation.

The lira lost more than half its value and inflation hit an eye-popping 85 percent since his experiment began.

Millions lost their savings and fell into deep debt.

Polls show the economy worrying Turks more than any other issue -- a point not lost on Kilicdaroglu.

The 74-year-old former civil servant pledges to restore economic order and bring in vast sums from Western investors who fled the chaos of Erdogan's more recent rule.

Kilicdaroglu's party will send out 300,000 monitors to Turkey's 50,000 polling stations to guarantee a fair outcome on election day.

Opposition security pointman Oguz Kaan Salici sounded certain about a smooth transition should Erdogan lose.

"Power will change hands the way it did in 2002," he said of the year Erdogan's party first won.

A Western diplomatic source pointed to Turkey's strong tradition of respecting election results.

Erdogan's own supporters turned against him when the Turkish leader tried to annul the opposition's victory in 2019 mayoral elections in Istanbul.

But the source observed a note of worry among Erdogan's rank and file.

"For the first time, (ruling party) deputies are openly evoking the possibility of defeat," the source said.

© Agence France-Presse

Fulya OZERKAN

Sat, April 29, 2023 a

Conservative Turkish women won the right to stay veiled in public under Recep Tayyip Erdogan's rule

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's two-decade domination of Turkey has seen some groups prosper and others suffer in the highly polarised country.

AFP looks at some of the winners and losers ahead of the May 14 parliamentary and presidential vote.

- Winners -

RELIGIOUS GROUPS:

The religious affairs directorate, or Diyanet, became a powerful force under Erdogan, a pious Muslim whose Islamic-rooted party has tested the secular foundations of post-Ottoman Turkey.

Diyanet has its own TV channel that it uses to weigh in on political debates, and enjoys a budget comparable to that of an average ministry.

Its expanded reach has turned it into a target of Erdogan's secular opponents, who complain about the growing number of mosques, Koran courses and the influence of religious sects.

Diyanet's former head, Mehmet Gormez, secured Erdogan's strong backing after becoming embroiled in controversy over his lavish lifestyle, which included the use of a flashy German car.

|

| ERDOGAN TAKES ADVANTAGE OF EARTHQUKE TO ADVERTISE |

CONSTRUCTION SECTOR:

Erdogan has spearheaded a building spree that has spurred growth but created controversial ties between government insiders and the winners of plump state contracts.

The development boom reshaped Turkey, offering modern homes to millions while filling ancient cities with high-rises.

The construction craze was accompanied by Erdogan's penchant for what he dubbed his "crazy projects".

These ambitious, mega-investments spanned Turkey with bridges, airports and high-speed rail. He even laid plans for a new canal to rival the Bosphorus Strait.

His detractors called them an environmental disaster that enriched government allies.

More than 200 contractors were arrested as part of a probe into safety violations that contributed to the death of more than 50,000 people in February's earthquake in Turkey's southeast.

CONSERVATIVE WOMEN:

Erdogan's government has championed the rights of conservative Muslims after decades of staunchly secular rule.

Some of the biggest gains were made by pious women, who were gradually allowed to start wearing headscarves at universities, in the civil service, parliament and the police.

The issue is personal for Erdogan, who has lamented how secular governments "did not allow my headscarf-wearing daughters" to go to university.

Erdogan's two daughters, Sumeyye and Esra, eventually studied abroad.

- Losers -

MEDIA:

Turkey's once-vibrant independent media scene -- admired by diplomats as a sign of pluralism -- has gradually withered under Erdogan.

Analysts estimate that 90 percent of Turkey's media are allied with the government.

Erdogan's government heavily taxed critical media and used cheap loans to encourage select businessmen to run newspapers and television channels.

This has been accompanied by a crackdown on opposition reporters, especially those in Kurdish media outlets, which gathered force after a failed 2016 coup.

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, Turkey is one of the world's most prolific jailers of journalists.

Turkey's P24 independent journalism platform says 64 reporters are currently in jail.

INFLUENCE OF THE MILITARY:

Turkey's army, a secular force with a history of staging coups, gradually lost its influence in politics.

The process accelerated after a renegade military faction staged a failed coup attempt in 2016, which Erdogan blamed on a Muslim preacher exiled in the United States.

Erdogan retaliated with purges that saw thousands of soldiers jailed -- hundreds of them for life.

The army's top brass was slashed back, hurting one of the most strategically located defence forces of the NATO alliance. The air force in particular lost some of its mostly highly trained pilots and officers.

- Mixed fortunes -

KURDS:

Repressed by past secular governments, Kurds helped Erdogan get elected and supported him early in his rule.

Erdogan tried to improve their cultural and linguistic rights, launching talks aimed at ending a Kurdish armed struggled for broader autonomy in Turkey's southeast.

But the community, estimated to be 15 to 20 million strong, came under pressure when those talks collapsed and violence resumed in 2015.

Dozens of Kurdish mayors were stripped of their elected office in 2019 and replaced by state trustees. The main pro-Kurdish party is in danger of being shut down over alleged terror ties.

MIDDLE CLASS:

Turkey enjoyed an economic boom during Erdogan's first decade in power that created a thriving new middle class.

But the economy has been lurching from one crisis to another since 2013.

Turkey's current gross domestic product -- a measure of a country's wealth -- has shrunk back down to levels at which it stood in the first five years of Erdogan's rule, according to the World Bank.

Unchecked inflation has erased the savings of millions, leaving many in deep debt.

Wars, Religion And Football: Five Faces Of Erdogan

By Anne CHAON

Recep Tayyip Erdogan has become one of the most divisive and important leaders of post-Ottoman Turkey

Abhorred and adored, Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been compared to sultans and pharaohs while stamping his outsized personality and domineering style on Turkey over 20 years.

Elected as prime minister and then as an uber-powerful president under a tailor-made constitution, Erdogan has become Turkey's most important and polarising leader in generations.

A builder, a political brawler and a campaign beast, here are five of Erdogan's most emblematic traits.

Filling Turkey with bridges, highways and airports, Erdogan has propelled the developing country into the 21st century with mega-investments, stimulating growth.

He calls them his "crazy projects": a towering third bridge over the Bosphorus, another one across the Sea of Marmara, a third spanning the Dardanelles Strait.

They all set records, as did Istanbul's Camlica Mosque -- the largest in Turkey, replete with six minarets and space for 30,000 worshippers.

But perhaps the grandest of the megaprojects is the Istanbul Canal, being built just west of the Bosphorus on land the city once envisioned as an evacuation zone in case of a long-feared earthquake.

There is much more, including high-speed rail, a third Istanbul airport -- designed to be the world's largest -- and power plants, including the country's first nuclear one, controversially built by Russia.

Raised in Istanbul's working-class district of Kasimpasa, the young Erdogan dreamt of little but football, kicking around a ball made of paper and rags, according to popular lore.

His tall frame -- 1.85 metres, or just over six feet -- made him a sought-after centre-forward.

Recep Tayyip Erdogan has had a lifelong love for football, almost becoming a player himself

He received offers from several professional clubs, including Istanbul's Fenerbahce.

But his father, an austere sailor from the Black Sea, told him to pursue religious studies.

Erdogan gave up reluctantly but remained a big fan, mingling with players throughout his career.

In 2014, businessmen with ties to Erdogan's ruling party acquired Basaksehir, the least storied of Istanbul's six clubs.

Based in a conservative district of the same name, Basaksehir quickly became a powerhouse, winning the league in 2020.

Erdogan's father would have approved if the future president had instead become an imam.

In the secular Turkey created by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, Erdogan attended one of the first religious public schools, combining studies of the Koran with other subjects.

Islam became the rallying cry of his electorate and its new movement, called the Justice and Development Party (AKP).

Erdogan advocates piety, frowns on smoking and drinking, and defends traditional family values at the expense of the LGBTQ community and emancipated women.

The AKP celebrates motherhood as well as the wearing of headscarves at school and in the civil service -- a right that Ataturk had abolished with Turkey's formation in 1923.

A master campaigner who comes alive on stage, Erdogan is a gifted public speaker who relishes a challenge, priding himself on never losing a national election.

Recep Tayyip Erdogan loves campaigning, taking pride in having never lost a national election

Derailed by stomach issues in recent days, past campaigns have seen Erdogan hop between eight cities in a day, giving impassioned speeches to crowds of supporters.

A populist and a performer, he announces pay hikes, kisses babies, hugs elderly women and even hands out small change to kids -- a custom on religious holidays.

Pro-government media, which now dominates, lap it all up, broadcasting his performances live across the nation and replaying them deep into the night.

Erdogan has leveraged Turkey's strategic position between Europe and the Middle East -- guarding the southern shores of the Black Sea and the northern ones of the Mediterranean -- to diplomatic advantage.

He assumed the role of mediator when Russia invaded Ukraine, becoming one of the few world leaders with open access to Vladimir Putin and Russia's vast energy resources.

But he also supplied Kyiv with weapons and won international plaudits for helping broker a deal to resume Ukraine's grain exports.

On the other hand, he drew Western wrath for launching incursions into Syria. At one stage, he appeared to be simultaneously brawling with all of Turkey's neighbours, stretching from Iraq to Greece.

He broke off relations with Israel and Egypt, intervened in the war in Libya, and helped Azerbaijan defeat Armenia in their 2020 war over Nagorno-Karabakh.

Facing a new economic crisis, Erdogan has been mending fences, seeking investments and engaging in "earthquake diplomacy" with Greece after a massive February shock killed more than 50,000 people.

© Agence France-Presse