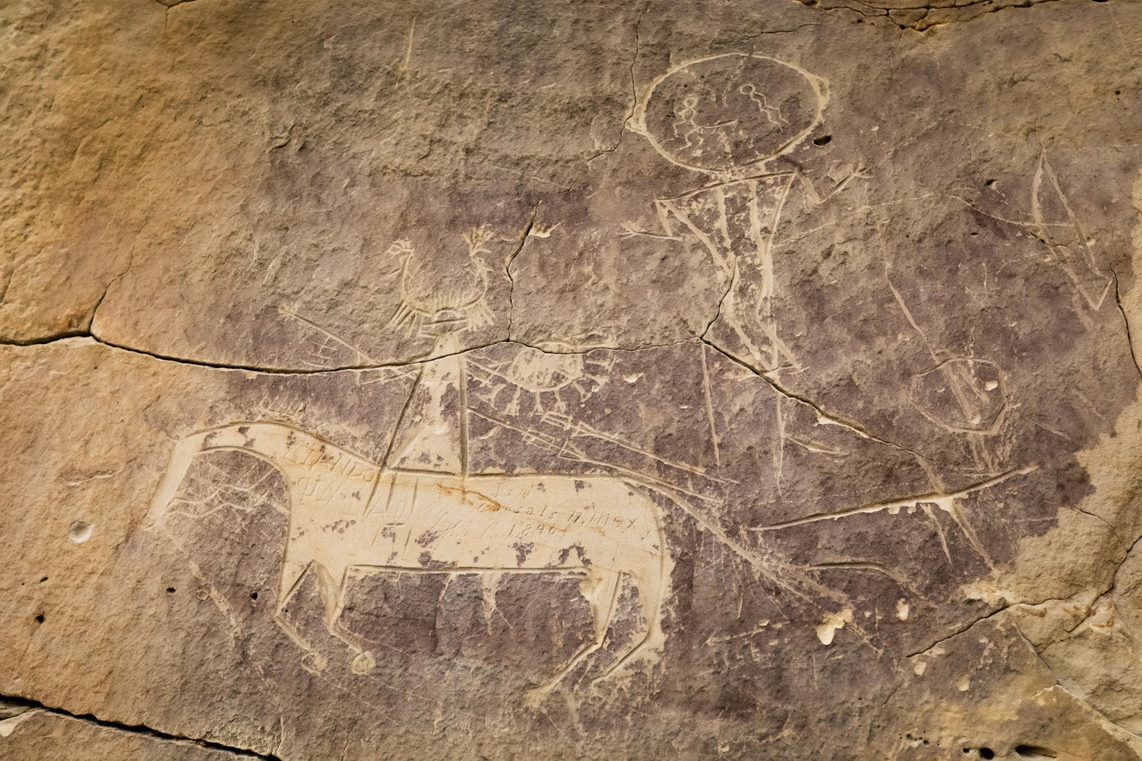

Man. "He Stalks one," and horse connect.

On March 30, 2023, the journal Science unveiled the collaborative work of an international team that united 87 scientists across 66 institutions around the world to begin to refine the history of the horse in the Americas – this time with Indigenous scientists and knowledge keepers leading the way. This work, which embeds cross-disciplinary and cross-cultural research between western and traditional Indigenous science, is a first step in a long-term collaboration.

“Horses have been part of us since long before other cultures came to our lands, and we are a part of them,” states Chief Joe American Horse, a leader of the Oglala Lakota Oyate, traditional knowledge keeper, and co-author of the study. The continent of North America is where horses first emerged. Despite the ancient and deep ancestral relationship many Indigenous Peoples of the Americas had – and have – with the Horse Nation, until this point there has been no place for the original Peoples of the Americas – or their horses - in this conversation. The global narrative was written around them, without them.

“This is very much a ‘first-step’ of a long-term collaboration. The narrative that all horses in North America come from Spaniards is a paradigm,” states Mario Gonzalez, Oglala Lakota tribal attorney and co-author of the study. He said the study intended to use Western genomics, Indigenous sciences and archeology to broaden that model. “We need to be innovative. Just because the Spanish brought horses, does not necessarily mean that we did not already have horses here, and it does not negate the Peoples who cared for those horses before they came to be known as ‘Spanish.’”

The purpose of this study was to test a narrative that features in almost every textbook on the history of the Americas that is based off of early European historic records. These accounts contend a recent adoption of horses by Indigenous Peoples across the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains following the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, an uprising of Indigenous Peoples against Spanish religious, cultural and economic control.

“Using both new and established practices from the archaeological sciences, our team identified evidence that horses were raised, fed, cared for, and ridden by Indigenous Peoples decades before the Pueblo Revolt,” states William Taylor, Assistant Professor at the University of Colorado, who performed this archeological analysis on the specimen samples together with a large team of partners, including his Lakota, Comanche, Pawnee and Pueblo collaborators. “Direct radiocarbon dating of discoveries ranging from Paa’ko Pueblo in New Mexico, southern Idaho to southwestern Wyoming and northern Kansas showed that horses were present across much of the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains conclusively before 1680.”

Importantly, this earlier dispersal and societal integration validates many traditional perspectives on the origin of the horse from project partners like the Comanche and Pawnee, who recognize the link between archaeological findings and oral traditions. Comanche Tribal Historian and study coauthor Jimmy Arterberry states: “These findings support and concur with Comanche oral tradition. Archaeological traces of our horse culture are invaluable assets that reveal a chronology in North American history, and are important to the survival of Indigenous cultures. They are our heritage, and merit honor through protection. They are sacred to the Comanche.”

This genomic collaboration between the Lakota team and the French team at the Centre for Anthropobiology and Genomics of Toulouse and Paul Sabatier University, led by Prof. Ludovic Orlando, proved invaluable, in that it acknowledged Indigenous scientific systems. For example, Lakota science focuses on the more than 99 percent of genomic relationality that was shown across global horse samples, while Western science tends to focus on the less than 1 percent genetic variance. These divergent viewpoints were published side by side in an unprecedented manner. Perhaps most importantly, the team is committed to future research together.

Western genomic analysis demonstrated that the horses surveyed in this study for many Plains Nations were primarily of Iberian ancestry, but not directly related with those horses that inhabited the Americas in the Late Pleistocene more than 12,000 years ago. Likewise, they were not the descendants of Viking horses, despite Viking establishing settlements on the American continent by 1021. This collaborative team is excited about what future steps will mean for Indigenous sciences and the world.

“For the Lakota, scientifically investigating the history of Šungwakaŋ, the Horse Nation, in the Americas is a perfect starting point to begin a global discussion in science, as it will necessarily highlight the places of connection and disconnection between Western and Indigenous approaches,” states Dr. Yvette Running Horse Collin, a traditional Lakota scientist who is also trained in ancient genomics and serves as a co-author of the study. “Our elders have been clear from the start: working with our relative the horse will provide a roadmap for learning how to combine the power of all scientific systems, traditional and western alike.”

The genome analyses did not just address the development of horsemanship within First Nations during the first stages of the American colonization. These analyses demonstrated that the once dominant ancestry found in the horse genome became increasingly diluted through time, gaining ancestry native from British bloodlines. Therefore, the changing landscape of colonial America was recorded in the horse genome: first mainly from Spanish sources, then primarily from British settlers.

In the future, this team is committed to continue working on the history of the Horse Nation in the Americas to include the scientific methodologies inherent in Indigenous scientific systems, as well as a greater contribution regarding migratory patterns and the effects on the genome due to climate change. This study was critical in helping to bring Western and Indigenous scientists together so that authentic dialogue and exchange may begin. “It made me a better scientist who does not necessarily take for granted what western science takes for granted based on one line of evidence,” Prof. Orlando said. “It opened my mind to new perspectives, new ways to frame problems, and I hope new ways to answer questions. It showed me the complexity of reality. How much all things are related. It was a two-way street and I hope I did the same for them.”

The challenges that our modern world faces are immense. In these times of massive biodiversity crisis and global climate warming, the future of the planet is threatened. Indigenous Peoples have survived the chaos and destruction brought about by colonization, assimilation policies and genocide, and carry important knowledge and scientific approaches centered around sustainability. It is now, more than ever, time to repair history and create more inclusive conditions for co-designing strategies for a more sustainable future. This study created a collaboration between western scientists and many Native Nations across the United States, from the Pueblo to the Pawnee, Wichita, Comanche, and Lakota.

We expect to be joined by many more soon. “Our Horse Nation relatives have always brought us together and will continue to do so. As this collaboration develops, we invite all Indigenous Peoples to join us. We call to you,” states Dr. Antonia Loretta Afraid of Bear-Cook, a traditional knowledge keeper for the Oglala Lakota and a study co-author.