Leading art museums are reassessing their works after a Belgian journalist traced how a fascist sympathiser acquired a Jewish dealer’s collection

Jennifer Rankin in Brussels

THE OBSERVER

Sat 20 May 2023

In August 1940, Samuel Hartveld and his wife, Clara Meiboom, boarded the SS Exeter ocean liner in Lisbon, bound for New York. Aged 62, Hartveld, a successful Jewish art dealer, left a world behind. The couple had fled their home city of Antwerp not long before the Nazi invasion of Belgium in May 1940, parting with their 23-year-old son, Adelin, who had decided to join the resistance.

Hartveld also said goodbye to a flourishing gallery in a fine art deco building in the Flemish capital, a rich library and more than 60 paintings. The couple survived the war, but Adelin was killed in January 1942. Hartveld was never reunited with his paintings, which were snapped up at a bargain-basement price by a Nazi sympathiser and today are scattered throughout galleries in north-western Europe, including Tate Britain.

The story of Hartveld’s lost paintings is just one episode in the vast catalogue of art that was looted, stolen or forcibly sold after Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933. Nearly 80 years after the end of the second world war, a new book, Kunst voor das Reich, argues that Belgium has yet to reckon with that legacy.

In August 1940, Samuel Hartveld and his wife, Clara Meiboom, boarded the SS Exeter ocean liner in Lisbon, bound for New York. Aged 62, Hartveld, a successful Jewish art dealer, left a world behind. The couple had fled their home city of Antwerp not long before the Nazi invasion of Belgium in May 1940, parting with their 23-year-old son, Adelin, who had decided to join the resistance.

Hartveld also said goodbye to a flourishing gallery in a fine art deco building in the Flemish capital, a rich library and more than 60 paintings. The couple survived the war, but Adelin was killed in January 1942. Hartveld was never reunited with his paintings, which were snapped up at a bargain-basement price by a Nazi sympathiser and today are scattered throughout galleries in north-western Europe, including Tate Britain.

The story of Hartveld’s lost paintings is just one episode in the vast catalogue of art that was looted, stolen or forcibly sold after Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933. Nearly 80 years after the end of the second world war, a new book, Kunst voor das Reich, argues that Belgium has yet to reckon with that legacy.

Portrait of Bishop Antonius Triest by Gaspar de Crayer.

Photograph: Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent / Michel Burez & Hugo Maertens

For the book’s author, Geert Sels, the quest began in 2014 after the sensational discovery of 1,500 modernist masterpieces in the flat of an 80-year old man in Munich, the son of the Nazi art dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt. Sels, the cultural editor of Belgium’s De Standaard newspaper, was intrigued. He wanted to know if any of the works had come from Belgium. But when he went to consult official records, he was disappointed: Belgium had no public database of lost or orphan art works.

According to the Belgian government, that was because everything was in order. A government commission into plundered Jewish assets had completed its work in 2001. “The answer was, everything in Belgium has been researched,” Sels told the Observer. “I thought, well, it’s a lie.”

Sels was convinced Belgium fell far short of the 1998 Washington principles, when 44 countries agreed to establish a central registry of art stolen by the Nazis and publicise confiscated works to help trace the original owners or heirs. “A lot of countries, including Belgium, agreed to do research, to make the information public, to establish databases but Belgium hasn’t done it.”

So he began his own search, which led him to Hartveld’s scattered collection. His library – 29 boxes of art books and auction catalogues – was carted away by the Nazis.

His gallery and paintings were sold to René Van de Broek, a 31-year-old painting restorer and member of DeVlag, a Flemish group that favoured cooperation with Nazi Germany. Van de Broek paid 200,000 francs for the exhibition hall and 66 paintings, later telling postwar investigators he believed it was a fair price. In fact it was a steal – Hartveld had taken out an 800,000 franc mortgage to build the property alone.

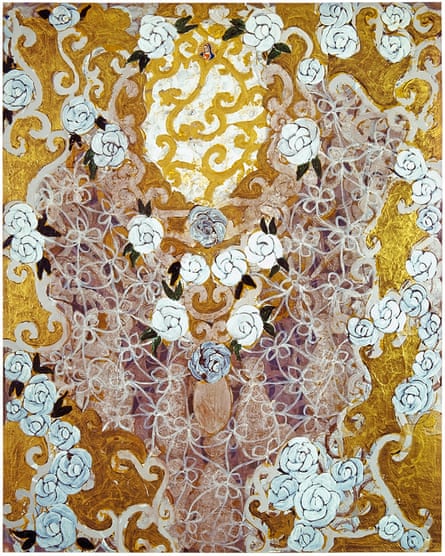

In 1948, Van de Broek sold a single painting – the 17th-century baroque work, Portrait of Bishop Antonius Triest – to the city of Ghent for 50,000 francs. Another of Hartveld’s 17th-century works, Aeneas and His Family Fleeing Burning Troy, now hangs in Tate Britain, acquired from a Belgian art dealer in 1994. Once thought to be an Italian painting, the 1654 work bears the signature of Canterbury “gentleman painter” Henry Gibbs and its theme of exile echoes the trauma of the recent English civil war.

Van de Broek, who was questioned after the war for his Nazi sympathies, convinced investigators he had Hartveld’s blessing to dispose of the paintings. A letter dated 5 July 1945, purporting to be from the art dealer, said Van de Broek had done “brilliantly” in saving his stock. As an expression of “sincere gratitude” he proposed that Van de Broek run the gallery and sell the stock if he wanted.

For a man who had lost his son and life’s work in a war that had just ended, the casual tone was jarring. Sels took the letter to a handwriting expert, who found significant discrepancies with Hartveld’s usual style and concluded there was “a strong possibility… the signature was not the hand of Monsieur S Hartveld”.

After researching the book, Sels wants to expand the concept of lost art. Hartveld never knew his works were being sold. Other “sales” or “donations” were acts of desperation.

For the book’s author, Geert Sels, the quest began in 2014 after the sensational discovery of 1,500 modernist masterpieces in the flat of an 80-year old man in Munich, the son of the Nazi art dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt. Sels, the cultural editor of Belgium’s De Standaard newspaper, was intrigued. He wanted to know if any of the works had come from Belgium. But when he went to consult official records, he was disappointed: Belgium had no public database of lost or orphan art works.

According to the Belgian government, that was because everything was in order. A government commission into plundered Jewish assets had completed its work in 2001. “The answer was, everything in Belgium has been researched,” Sels told the Observer. “I thought, well, it’s a lie.”

Sels was convinced Belgium fell far short of the 1998 Washington principles, when 44 countries agreed to establish a central registry of art stolen by the Nazis and publicise confiscated works to help trace the original owners or heirs. “A lot of countries, including Belgium, agreed to do research, to make the information public, to establish databases but Belgium hasn’t done it.”

So he began his own search, which led him to Hartveld’s scattered collection. His library – 29 boxes of art books and auction catalogues – was carted away by the Nazis.

His gallery and paintings were sold to René Van de Broek, a 31-year-old painting restorer and member of DeVlag, a Flemish group that favoured cooperation with Nazi Germany. Van de Broek paid 200,000 francs for the exhibition hall and 66 paintings, later telling postwar investigators he believed it was a fair price. In fact it was a steal – Hartveld had taken out an 800,000 franc mortgage to build the property alone.

In 1948, Van de Broek sold a single painting – the 17th-century baroque work, Portrait of Bishop Antonius Triest – to the city of Ghent for 50,000 francs. Another of Hartveld’s 17th-century works, Aeneas and His Family Fleeing Burning Troy, now hangs in Tate Britain, acquired from a Belgian art dealer in 1994. Once thought to be an Italian painting, the 1654 work bears the signature of Canterbury “gentleman painter” Henry Gibbs and its theme of exile echoes the trauma of the recent English civil war.

Van de Broek, who was questioned after the war for his Nazi sympathies, convinced investigators he had Hartveld’s blessing to dispose of the paintings. A letter dated 5 July 1945, purporting to be from the art dealer, said Van de Broek had done “brilliantly” in saving his stock. As an expression of “sincere gratitude” he proposed that Van de Broek run the gallery and sell the stock if he wanted.

For a man who had lost his son and life’s work in a war that had just ended, the casual tone was jarring. Sels took the letter to a handwriting expert, who found significant discrepancies with Hartveld’s usual style and concluded there was “a strong possibility… the signature was not the hand of Monsieur S Hartveld”.

After researching the book, Sels wants to expand the concept of lost art. Hartveld never knew his works were being sold. Other “sales” or “donations” were acts of desperation.

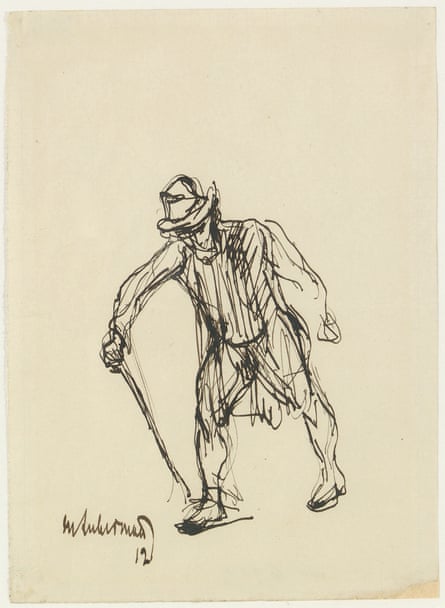

Homme marchant by Max Liebermann.

Photograph: Royal Museums of Fine Arts, Belgium

In 1939, a Jewish immigrant to Belgium from Berlin, Benno Seegall, offered the Brussels Museum of Fine Arts 10 drawings from the family collection, after an earlier donation of two works, to secure visas for his sister. Emmy Seegall and her husband, Fritz Gütermann, were frantically trying to flee Germany after the Kristallnacht pogroms of November 1938, but had been turned down for a Belgian visa multiple times.

Benno, who had lived in Brussels since 1936, secured visas with avant garde works by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Max Liebermann. The drawings remain in the museum’s collection today. For Sels, this is a very clear case: “They wouldn’t have given away things if it was not to save their lives and get away from Germany.”

In a statement, Belgium’s state secretary in charge of museums, Thomas Dermine, said the previous government commission had restored a large number of looted works, but subsequent restitutions had been “too sporadic”. He was, the statement said, creating a department that would charge federal museums with considering “a process that allows a more proactive approach to this issue” because “humanity must always end up defeating barbarism”.

The Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium (RMFAB) said further research into the unknown provenance of some of its paintings “must be carried out” and could lead to new restitutions. The museums, which last year returned an expressionist work to the descendants of a German Jewish couple, said it was studying the works from the Seegalls as part of a larger, four-year project into the provenance of its collections acquired since 1933. “The RMFAB strongly hopes that this project will allow it to complete the provenance of art works in its collection… and will ensure greater transparency.”

Professor Dr Manfred Sellink, director of the Museum of Fine Arts Ghent, said there had been no claim to recover the portrait of Bishop Antonius Triest. Any decision on restitutions would be taken by the city of Ghent, the owner of the museum’s collection. His museum, he said, had researched works of doubtful provenance and always collaborated in the return of stolen objects, but he acknowledged there could be problematic works in the collection. “I can say without hesitation, the Belgian state has been very late in taking action,” Sellink added.

Tabitha Barber, curator of British art at Tate Britain, said the museum was doing careful work to verify its Aeneas painting has been correctly identified: “We are in the process of doing this and will update our provenance record accordingly.”

Meanwhile, Sels has traced several relatives of the Jewish families who lost art works during the war. He thinks their claims will heighten pressure on the Belgium government to act: “It won’t be enough to say everything has been studied and no irregularities were found.”

In 1939, a Jewish immigrant to Belgium from Berlin, Benno Seegall, offered the Brussels Museum of Fine Arts 10 drawings from the family collection, after an earlier donation of two works, to secure visas for his sister. Emmy Seegall and her husband, Fritz Gütermann, were frantically trying to flee Germany after the Kristallnacht pogroms of November 1938, but had been turned down for a Belgian visa multiple times.

Benno, who had lived in Brussels since 1936, secured visas with avant garde works by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Max Liebermann. The drawings remain in the museum’s collection today. For Sels, this is a very clear case: “They wouldn’t have given away things if it was not to save their lives and get away from Germany.”

In a statement, Belgium’s state secretary in charge of museums, Thomas Dermine, said the previous government commission had restored a large number of looted works, but subsequent restitutions had been “too sporadic”. He was, the statement said, creating a department that would charge federal museums with considering “a process that allows a more proactive approach to this issue” because “humanity must always end up defeating barbarism”.

The Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium (RMFAB) said further research into the unknown provenance of some of its paintings “must be carried out” and could lead to new restitutions. The museums, which last year returned an expressionist work to the descendants of a German Jewish couple, said it was studying the works from the Seegalls as part of a larger, four-year project into the provenance of its collections acquired since 1933. “The RMFAB strongly hopes that this project will allow it to complete the provenance of art works in its collection… and will ensure greater transparency.”

Professor Dr Manfred Sellink, director of the Museum of Fine Arts Ghent, said there had been no claim to recover the portrait of Bishop Antonius Triest. Any decision on restitutions would be taken by the city of Ghent, the owner of the museum’s collection. His museum, he said, had researched works of doubtful provenance and always collaborated in the return of stolen objects, but he acknowledged there could be problematic works in the collection. “I can say without hesitation, the Belgian state has been very late in taking action,” Sellink added.

Tabitha Barber, curator of British art at Tate Britain, said the museum was doing careful work to verify its Aeneas painting has been correctly identified: “We are in the process of doing this and will update our provenance record accordingly.”

Meanwhile, Sels has traced several relatives of the Jewish families who lost art works during the war. He thinks their claims will heighten pressure on the Belgium government to act: “It won’t be enough to say everything has been studied and no irregularities were found.”