Labourers and children of Indian heritage walking down a street in Guyana in the early 1920s. The Field Museum Library, CC BY-SA

My father never spoke to us about Guyana, the country of his birth, when we were growing up because he believed that his history had no value to his children. In doing this, he was unconsciously copying his grandparents, as well as others in his community, who had collectively chosen not to talk about their past.

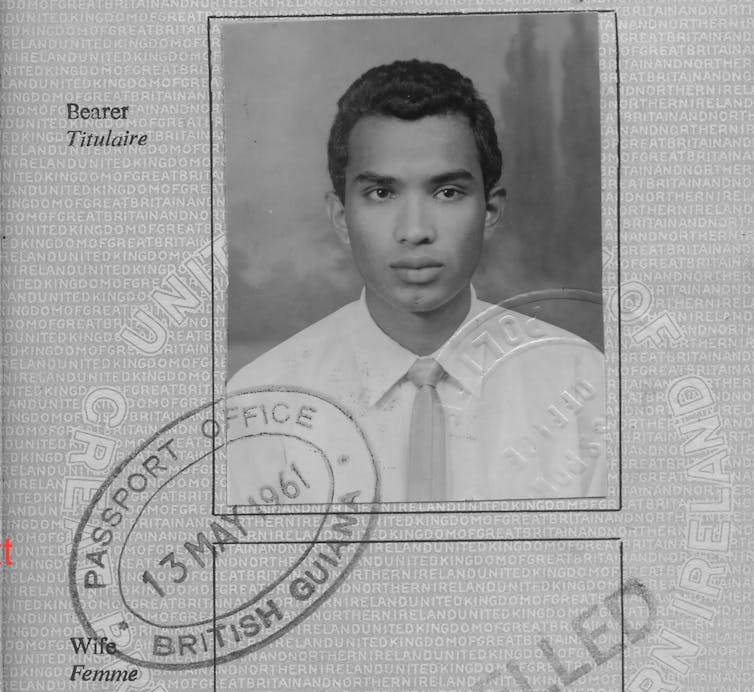

Sadly, in our case, this familial silence was like a bullet that ricocheted down the generations. It was fired in 1886 when my 22-year-old great-grandfather was recruited from India as an indentured labourer to travel to British Guiana (the spelling changed to Guyana in 1966 after independence) on a ship called the Foyle. It went on to the vessel that carried my father to Britain from Guyana in 1961, before taking aim at my brothers and I – a group of disaffected and confused children who had no real understanding of what our cultural heritage was.

When my father, Surujpaul Kaladeen, left Guyana, aged 23, he joined half a million other people from the Caribbean who made the journey to a new life in the UK between 1948 and 1971. This group of people became known as the Windrush generation.

When people think about the Windrush generation the images they tend to associate with this period are the black and white photos taken of African-Caribbean people at Tilbury Docks or Waterloo train station.

Sadly, in our case, this familial silence was like a bullet that ricocheted down the generations. It was fired in 1886 when my 22-year-old great-grandfather was recruited from India as an indentured labourer to travel to British Guiana (the spelling changed to Guyana in 1966 after independence) on a ship called the Foyle. It went on to the vessel that carried my father to Britain from Guyana in 1961, before taking aim at my brothers and I – a group of disaffected and confused children who had no real understanding of what our cultural heritage was.

When my father, Surujpaul Kaladeen, left Guyana, aged 23, he joined half a million other people from the Caribbean who made the journey to a new life in the UK between 1948 and 1971. This group of people became known as the Windrush generation.

When people think about the Windrush generation the images they tend to associate with this period are the black and white photos taken of African-Caribbean people at Tilbury Docks or Waterloo train station.

Jamaican immigrants meet RAF officials after Empire Windrush landed them at Tilbury Docks, Essex, on June 22 1948. PA Images / Alamy Stock Photo

They are unlikely to imagine someone like my father, who was not black but a person of Indian-Caribbean heritage. It took me many years to unpick my family history and to understand that we were not the only ones to experience this kind of cultural amnesia growing up.

When my son was born in 2013, I began to understand myself in the context of being an “invisible passenger in two imperial migrations”. Because, not only was the system of indenture generally unknown to the wider public, but as a consequence, the presence of Indian people in the Caribbean was also unknown. So, we were never recognised as part of the Windrush generation.

The fact that we did not look like we were part of a discernible community and that we were constantly faced with questions about our origins, was difficult for us growing up. I believe it was a contributory factor to the tragic outcomes that followed for my brothers.

The system of indenture was started in Mauritius in 1834 so that the British could cheaply replace enslaved Africans following the abolition of slavery in the British empire.

Under the British empire over two million people of Indian heritage were transported, through the indenture system, to countries on five different continents. While you will encounter British people of Indian-Mauritian, Indian-South African and Indian-Fijian heritage in the UK, the system of indenture that brought their ancestors to those countries is entirely absent from school curriculums and until recently, university syllabuses too.

But what has also helped Britain “forget” the creation and maintenance of the system of indenture across the 19th and early 20th centuries is the community’s own attitude to its past. Many of my great-grandparent’s generation connected their poverty and their departure from India – with its associated rupture of family ties – to feelings of shame.

Caribbean heritage, but not black

In some ways, I now look at my life as an academic as one long love letter to my older brothers. I wanted to understand the role that the absence of knowing our father’s history had played in shaping us as children, before we ever really had a chance to form questions about who we were.

In 1886 the iron ship, Foyle, carried people from India to British Guiana where they would work as indentured labourers on plantations.

State Library of South Australia, CC BY-SA

I have dedicated my academic career to an exploration of the history and literature of indenture and my book, The Other Windrush, edited with the academic and author David Dabydeen, is about the lives of people who grew up like me: descendants of the system of indenture whose history was unknown to the wider world.

In the early 2000s I embarked on archival research for my MA and subsequent PhD on colonial writing on indentured Indians in Guyana, which sits between Venezuela and Suriname, and is the only English-speaking country in South America. Guyana is part of the mainland Caribbean region.

I was convinced that in understanding the series of events that had led my ancestors from India to the Caribbean in the 19th century, I would in turn be able to work out what had happened to my brothers: gifted, bright, and beautiful boys who had stumbled catastrophically into adulthood.

Whether expressed through prison sentences, addiction or homelessness, their existence seemed to be a rejection of anything that resembled a normal life.

We were of Caribbean heritage, but not black. We were further of mixed heritage as our mum was white, but nobody used these labels in those days and to the world outside we were simply “pakis” – the word British racists used as a pejorative slur for anyone of South Asian heritage.

What I did not understand then, and what I have come to understand only recently, is that any comprehension of the role that indenture played in our lives was incomplete without understanding my father’s journey from the Caribbean to the UK as part of the Windrush generation.

I have dedicated my academic career to an exploration of the history and literature of indenture and my book, The Other Windrush, edited with the academic and author David Dabydeen, is about the lives of people who grew up like me: descendants of the system of indenture whose history was unknown to the wider world.

In the early 2000s I embarked on archival research for my MA and subsequent PhD on colonial writing on indentured Indians in Guyana, which sits between Venezuela and Suriname, and is the only English-speaking country in South America. Guyana is part of the mainland Caribbean region.

I was convinced that in understanding the series of events that had led my ancestors from India to the Caribbean in the 19th century, I would in turn be able to work out what had happened to my brothers: gifted, bright, and beautiful boys who had stumbled catastrophically into adulthood.

Whether expressed through prison sentences, addiction or homelessness, their existence seemed to be a rejection of anything that resembled a normal life.

We were of Caribbean heritage, but not black. We were further of mixed heritage as our mum was white, but nobody used these labels in those days and to the world outside we were simply “pakis” – the word British racists used as a pejorative slur for anyone of South Asian heritage.

What I did not understand then, and what I have come to understand only recently, is that any comprehension of the role that indenture played in our lives was incomplete without understanding my father’s journey from the Caribbean to the UK as part of the Windrush generation.

What was indenture?

Indians were taken from India to work on colonial sugar, rubber, tea and cocoa plantations in the 19th and early 20th century. By the time indenture was abolished in 1917, the system had spread from Mauritius and the Caribbean to Fiji, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Malaysia and beyond.

Considering the enormity of the system of indenture, which transported over two million men, women and children from India to parts of the British empire across the globe, it is surprising that it is so rarely acknowledged in public institutions in the UK. Indeed, the silence that surrounds it perhaps indicates how troubling its presence is in British imperial history as it disrupts the idea of the British empire as an institution that did not profit from exploitative systems of unfree labour after the abolition of slavery.

When indenture was abolished it left an overseas Indian community scattered across the world.

This article is part of our Windrush 75 series, which marks the 75th anniversary of the HMT Empire Windrush arriving in Britain. The stories in this series explore the history and impact of the hundreds of passengers who disembarked to help rebuild after the second world war.

A few facts unite the stories of those Indian communities: most never returned to India, despite their right to a free passage on completion of their indenture and a period of residence in the colony; and they spoke rarely or selectively about the past and what had led them to agree to travel so far.

Undoubtedly, many Indian indentured immigrants were duped into making the journey. It was common, for example, for recruiters to lie about the type of work and the amount of pay involved. But we also know that others made decisions to indenture based on an understanding that it could offer an escape from familial or societal pressures, famine and poverty.

In Guyana and Trinidad, the system itself sought to encourage Indian workers to remain in the country by offering a bounty or a plot of land to those that re-indentured. When considering the power of the plantation economy in individual countries and its ability to encircle workers, it is perhaps unsurprising that people made the decision to stay in their new homes, particularly in cases where they had left challenging family circumstances.

The population of the Caribbean was transformed by the system of indenture and not only from Indian labourers. Chinese indentured labourers arrived in Guyana and Trinidad in 1853 and to Jamaica in 1854. By the time the indenture system had been abolished in 1917, close to 18,000 Chinese and almost 450,000 Indians had been brought to the British Caribbean.

‘Collective amnesia’

I remember a scene in a BBC documentary about indenture, from 2002, called Coolies: How Britain Reinvented Slavery. In that scene my colleague, David Dabydeen, is standing among paper fragments and neglected records in an old post office in Guyana.

Whispering, so that no one will hear him and be offended, he speaks to the camera in his beautiful Berbice-to-Tooting-to-Cambridge drawl: “I believe that people don’t want to remember the past,” he says.

It’s a past of shame it’s not something they want to preserve in the way that in England you would preserve castles or Arthurian legend.

In this he is supported by the Guyanese historian, Clem Seecharan, who frequently refers to a type of “collective amnesia” affecting the first generation of Indian indentured immigrants to the Caribbean, who internalised both the shame of being part of a system that subjugated them and, in many cases, also carried the burden of a complicated past in India.

When I was growing up the term Windrush generation had not yet been coined and work in universities on the idea of “Indian-Caribbean” as an identity and a diaspora, had not yet begun. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why there was no vocabulary to express who we were.

David, the ‘true child of Windrush’

My oldest brother David was born in 1965 and was a true child of Windrush and when I say that I mean it in the sense that he experienced the worst of the prejudice of this period. Born when my parents were living in a rented room that they had struggled to find, he accompanied them on their journey to flat rental and eventual home ownership.

There is a photo of David standing outside our family home around 1974, he is just about smiling I think, and squinting because the sun is in his eyes. To me, he appears to be looking out at an unknown future that perhaps, because of this new house, seems a little brighter than before.

The author’s older brother David in 1974.

Author provided (no reuse)

When David died in his early forties in 2008, having lived much of his adult life as a rough sleeper, my father was haunted by the decisions that he had made when we were children, believing that if he had just acted at a particular moment, David’s life could have been completely different.

He focused particularly on an occasion when David was racially attacked at school and another boy had hit him with a cricket bat. The incident had been serious enough to cause his head to bleed badly and my dad lamented that he had not immediately removed him from this school, which was famous in our area for being somewhere you survived rather than attended. Each of us have stories about David like this.

For my mum it was the night that David was stopped by the police and subjected to a humiliating strip search in a police van, despite explaining to the police that his house was 100 metres away and that if they knocked on the door, my mother would happily explain that the bike he was wheeling was not stolen: it was his.

I was a little girl at this time, perhaps only nine or ten years old, but I remember that even my mum, who famously “didn’t get” why we had a problem with racism, was angry. Like a million white women before her she had crossed the colour bar with certain misconceptions intact – the justice and the fairness of the British police was one of them.

Nobody asked us initially to identify his body because in typical David fashion he had always slept with his birth certificate on his person, in a plastic wallet, safe from the elements. My youngest brother, Eddie, who was born in 1973, refused to believe that the body in the hospital mortuary was David’s. As my father and I stood at the edges of the room, Eddie broke free and ran to his brother, touching his face as he repeated his name in disbelief.

When David died in his early forties in 2008, having lived much of his adult life as a rough sleeper, my father was haunted by the decisions that he had made when we were children, believing that if he had just acted at a particular moment, David’s life could have been completely different.

He focused particularly on an occasion when David was racially attacked at school and another boy had hit him with a cricket bat. The incident had been serious enough to cause his head to bleed badly and my dad lamented that he had not immediately removed him from this school, which was famous in our area for being somewhere you survived rather than attended. Each of us have stories about David like this.

For my mum it was the night that David was stopped by the police and subjected to a humiliating strip search in a police van, despite explaining to the police that his house was 100 metres away and that if they knocked on the door, my mother would happily explain that the bike he was wheeling was not stolen: it was his.

I was a little girl at this time, perhaps only nine or ten years old, but I remember that even my mum, who famously “didn’t get” why we had a problem with racism, was angry. Like a million white women before her she had crossed the colour bar with certain misconceptions intact – the justice and the fairness of the British police was one of them.

Nobody asked us initially to identify his body because in typical David fashion he had always slept with his birth certificate on his person, in a plastic wallet, safe from the elements. My youngest brother, Eddie, who was born in 1973, refused to believe that the body in the hospital mortuary was David’s. As my father and I stood at the edges of the room, Eddie broke free and ran to his brother, touching his face as he repeated his name in disbelief.

Eddie, ‘the centre of my life growing up’

Two years ago, I cradled the scatter tube that held Eddie’s ashes in my arms as my husband drove me to the crematorium where we had left David 13 years before. Found dead in his flat in the middle of the pandemic, he had survived longer than anyone who loved him thought that he might.

In my eyes, his life since adolescence had been a long flirtation with death and each of us had made dashes across London to various hospitals where he had been taken after overdoses or as a result of being sectioned. In my mind, when I enter our childhood house and wander around the rooms looking for pieces of our story, I inevitably find Eddie, who was the centre of my life growing up.

The author in a school photo with older brother, Eddie, in the early 1980s.

Author provided (no reuse)

Two years older than me, Eddie was the person in my childhood who I admired most. He was a strong, athletic boy who could draw, programme computers, skateboard like a demon and write incredible stories. I looked up to him enormously and refused to consider any of the accumulating evidence that he was lying to me regularly, right up until the point that a local drug dealer arrived on our doorstep demanding to see him.

Perhaps there is no intimacy like that of a sibling relationship. There are parts of ourselves that are known exclusively to the people who watched us when we were in formation. I am aware that in losing David and Eddie, I have also lost parts of myself; memories that are irretrievable without them.

It is of course impossible to know if my brothers’ lives would have been different if they had a better sense of our father’s history and heritage. But the void we felt as children and the way in which this absence of familial history affected them, motivated my studies.

Two years older than me, Eddie was the person in my childhood who I admired most. He was a strong, athletic boy who could draw, programme computers, skateboard like a demon and write incredible stories. I looked up to him enormously and refused to consider any of the accumulating evidence that he was lying to me regularly, right up until the point that a local drug dealer arrived on our doorstep demanding to see him.

Perhaps there is no intimacy like that of a sibling relationship. There are parts of ourselves that are known exclusively to the people who watched us when we were in formation. I am aware that in losing David and Eddie, I have also lost parts of myself; memories that are irretrievable without them.

It is of course impossible to know if my brothers’ lives would have been different if they had a better sense of our father’s history and heritage. But the void we felt as children and the way in which this absence of familial history affected them, motivated my studies.

Who was my father?

As I progressed through my PhD my father, and his siblings who had moved to Canada after his migration to the UK, shared what they knew about their parents and grandparents with me. My father, who was born in 1938, in particular remembered his maternal grandfather, who unlike his paternal grandfather had come from the south of India and with whom he spent every summer growing up. Among the stories about this grandfather that he and his older brother shared with me were those of the Kali Mai Puja, an important religious celebration for South Indians in Guyana.

A minority within a minority: the passport of Surujpaul Kaladeen from 1961.

Author provided (no reuse)

I understood that much of my father’s reluctance to speak about the past was connected not only to his parents’ and grandparents’ omissions, but also the ideas he had garnered throughout his childhood that his history did not have the same value as that of his colonisers.

The superiority of everything British was an idea that had been absorbed throughout his boyhood in Guyana which remained a colony until 1966. Every aspect of his education was connected to Britain, and he spoke to me often, after he had retired, about a textbook that he remembered with great affection called the Royal Reader. It was in this book that he had encountered one of his favourite poems by Tennyson called The Brook.

In an echo of the silence of our childhood, I discovered, after my mother’s death in 2019, that he had managed to hide an early diagnosis of dementia from both her and us for over four years. In the remaining time we had left, as his illness worsened, he would share a story with me about his daily journey to Peter’s Hall primary school, the school that served the children of the sugar estate of the same name. In this tale he would recall his first teacher and the walk home from school where he would pass his uncles who were working as canecutters on the sugar estate.

He spoke often of his South Indian grandfather, Swantimala, and I remembered a story that his older brother had told me many years before, about how my father had nearly died as a toddler, but that Swantimala had come to the house and asked his daughter, my grandmother, for permission to take care of him during his illness. He returned with him only once he had recovered.

To me this story represented everything that we had lacked growing up in London: the wonder of an extended family and the security of being born into a community of others like you.

I imagined this handsome, dark-skinned, grey-haired man striding off down the road with my dad in his arms and his daughter, looking on, safe in the knowledge that he could make everything right.

I understood that much of my father’s reluctance to speak about the past was connected not only to his parents’ and grandparents’ omissions, but also the ideas he had garnered throughout his childhood that his history did not have the same value as that of his colonisers.

The superiority of everything British was an idea that had been absorbed throughout his boyhood in Guyana which remained a colony until 1966. Every aspect of his education was connected to Britain, and he spoke to me often, after he had retired, about a textbook that he remembered with great affection called the Royal Reader. It was in this book that he had encountered one of his favourite poems by Tennyson called The Brook.

In an echo of the silence of our childhood, I discovered, after my mother’s death in 2019, that he had managed to hide an early diagnosis of dementia from both her and us for over four years. In the remaining time we had left, as his illness worsened, he would share a story with me about his daily journey to Peter’s Hall primary school, the school that served the children of the sugar estate of the same name. In this tale he would recall his first teacher and the walk home from school where he would pass his uncles who were working as canecutters on the sugar estate.

He spoke often of his South Indian grandfather, Swantimala, and I remembered a story that his older brother had told me many years before, about how my father had nearly died as a toddler, but that Swantimala had come to the house and asked his daughter, my grandmother, for permission to take care of him during his illness. He returned with him only once he had recovered.

To me this story represented everything that we had lacked growing up in London: the wonder of an extended family and the security of being born into a community of others like you.

I imagined this handsome, dark-skinned, grey-haired man striding off down the road with my dad in his arms and his daughter, looking on, safe in the knowledge that he could make everything right.

The author’s South Indian great-grandfather, Swantimala.

Author provided (no reuse)

I hoped that if my father, who died earlier this year, lost other memories, some trace of this sensation he would have had as a toddler could remain. That he was the beloved grandson of a man who loved his daughter, and a daughter who in turn trusted her father. A child who was in that moment safe in the land of his birth – peaceful and unaware of all that he would one day leave behind.

I hoped that if my father, who died earlier this year, lost other memories, some trace of this sensation he would have had as a toddler could remain. That he was the beloved grandson of a man who loved his daughter, and a daughter who in turn trusted her father. A child who was in that moment safe in the land of his birth – peaceful and unaware of all that he would one day leave behind.

Any sound is better than silence

I was in the middle of my doctorate when David died in 2008. For over a year I was unable to write or do any research. In the face of his death the recovery of our history seemed a pointless practice that would change nothing for him. I revisited these emotions in 2021 when Eddie died in the build-up to the launch of The Other Windrush.

In the same documentary that features David Dabydeen’s search for his great-grandfather’s indenture records in Guyana, the late Indian-Fijian historian Brij Lal speaks of the dedication of his entire adult life, to the study of indenture. He says he is “haunted” by the “ghosts of the past”. He adds: “It’s very emotional because I am not talking about a group of people in the abstract, I’m talking about people from whom I’m descended.”

I am unable to give these memories of Swantimala and the comforting roots they provide to my brothers. It is of course too late for that.

But in those moments where it has felt nothing can counter the pain of their loss, that this work does not matter, I am reminded that the research itself is an act of resistance and that in advocating for the history of the “ghosts of the past”, any sound I can make is better than silence.

Published: June 6, 2023 12.33pm EDT

Author

Author

María del Pilar Kaladeen

Associate Fellow, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London

Associate Fellow, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London

For you: more from our Insights series:

James McCune Smith: new discovery reveals how first African American doctor fought for women’s rights in Glasgow

Beatrix Potter’s famous tales are rooted in stories told by enslaved Africans – but she was very quiet about their origins

‘I’m always delivering food while hungry’: how undocumented migrants find work as substitute couriers in the UK