Volcanoes: The Fiery Future Of Green Energy

- Scientists believe that magma from volcanoes, rich in metals like copper, nickel, and zinc, could be harnessed as an alternative to environmentally damaging mining operations.

- Volcanoes, both active and dormant, could also be a significant source of geothermal energy, transforming energy-intensive mining operations into carbon-neutral processes.

- The concept requires substantial investment in research and technology to understand geology and develop methods to extract these resources from volcanoes.

Governments and private companies worldwide are looking at innovative new ways to generate renewable energy and support a green transition. Thanks to stronger climate policies in several countries, and a significant boost in public and private funding in recent years, several breakthroughs have been seen in the world of renewables. This includes both the variety of clean energy sources we have access to, new green technologies, and greater knowledge about the potential to tap into previously unthought-of energy sources. One such option is volcanoes, which scientists are suggesting could be a major source of both geothermal energy and the provision of metals needed for a global green transition.

As we make a collective shift away from fossil fuels to green alternatives in a bid to reduce the world’s greenhouse gas emissions and slow the effects of climate change, one big concern is the growing need for metals to support this move. The demand for metals, such as copper, nickel, and zinc, is increasing as greater amounts are required for new renewable energy operations, with cobalt production expected to grow sixfold and silver by half as much again by 2050. But to meet this demand, mining activities worldwide will need to increase exponentially, potentially posing a new threat to the environment, just as we move away from fossil fuels. In response to this threat, energy experts and scientists have been hurriedly researching other ways to access these metals.

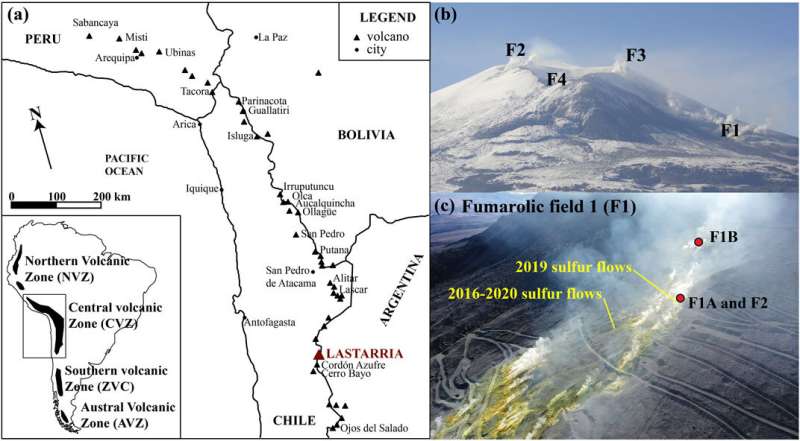

One way in which researchers now believe they may be able to get these metals without new mining operations is in the magma from volcanoes. In May, Olivia Hogg and Jon Blundy wrote in Geoscientist about the potential of harnessing the power of volcanoes, rather than looking at potentially damaging alternatives such as deep-sea mining. The magma found in volcanoes is extremely rich in metals. In fact, active volcanoes such as Mount Etna in Italy release around 20 tonnes of copper and 10 kg of gold a day in the form of volcanic gases. While metals cannot be extracted from volcanic gas, it may be possible to mine them from hot magmatic brines in the volcano.

The metals found in these brines are highly concentrated. And with around 2,000 volcanoes worldwide, this could provide a huge source of important metals. Both active and dormant volcanoes may be suitable for metal extraction. The mining of metals is already linked to magma, but typically that which is found in the Earth’s crust and mantle. It may be possible to directly mine brings from hot magmatic rocks, such as those under dormant volcanoes, which would allow metals to be extracted from a concentrated solution rather than solid rock. In addition, Hogg and Blundy believe the hot fluids found in volcanoes could be used to produce geothermal power to make the metal extraction process carbon neutral, meaning there would potentially no longer be a need for the energy-intensive processes associated with typical mining operations.

While there is abundant geothermal energy hidden inside the earth, accessing it has not always been so easy. The tools needed to access and extract this energy effectively did not exist in the past, meaning that there has been significant underinvestment in geothermal technologies in previous decades as it was thought of as a lost cause. However, as governments push a green transition and support research and innovation into a diverse range of green energy sources, we are gradually gaining a better understanding of geothermal energy and how we might harness its power.

Geothermal energy typically comes from underground, produced by converting heat energy from underneath the Earth’s crust. Energy is accessed by digging one-mile-deep wells to reach underground reservoirs to access steam and hot water, which can turn turbines connected to electricity generators. New technologies have enabled several countries to tap into their geothermal resources in recent years, including Iceland, El Salvador, New Zealand, Kenya, and the Philippines. In fact, geothermal energy meets more than 90 percent of Iceland’s heating demand.

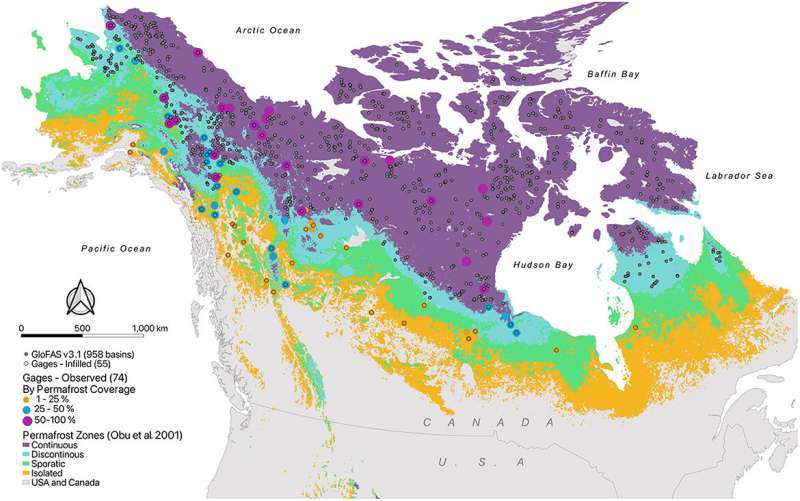

But now, scientists are suggesting that volcanoes may be an abundant source of geothermal energy. Researchers from the Geological Survey of Canada have been investigating whether it is possible to access geothermal energy from Mount Meager and Mount Cayley. So far, their research suggests that there is a “high potential” for extracting geothermal energy from volcanoes in Canada, especially Mount Meager. As it continues to release volcanic gasses, it shows that the volcano remains fairly active. Both volcanoes at on top of extremely hot underground reservoirs that could be used to generate electricity. But to access this geothermal energy, hot liquid would need to be pumped into facilities nearby, requiring drilling to release steam from the reservoir. This steam could power a turbine, in the same way as conventional geothermal energy production. However, just as with accessing geothermal energy from underground, significant investment in research and exploration may be required to harness this power.

As more funding is pumped into research and innovation in a broad green energy mix and related technologies, scientists and energy experts are increasingly seeing the potential of previously overlooked energy sources. It is probable that countries could access both the metals needed to support renewable energy projects and geothermal energy from their dormant volcanoes. But putting this into practice will require much more research and understanding of the geology, as well as investment in the equipment needed to launch these operations.

By Felicity Bradstock for Oilprice.com