New radar technique lets scientists probe invisible ice sheet region on Earth and icy worlds

IMAGE: A HELICOPTER EQUIPPED WITH AN ICE-PENETRATING RADAR REFUELS ON THE ICE AT THE ARCTIC’S DEVON ISLAND. RESEARCHERS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS INSTITUTE FOR GEOPHYSICS HAVE DEVELOPED A RESOLUTION-BOOSTING TECHNIQUE FOR THE INSTRUMENT. view more

CREDIT: UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS INSTITUTE FOR GEOPHYSICS/COREY SKENDER

Scientists at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG) have developed a radar technique that lets them image hidden features within the upper few feet of ice sheets. The researchers behind the technique said that it can be used to investigate melting glaciers on Earth as well as detect potentially habitable environments on Jupiter’s moon Europa.

The near-surface layers of ice sheets are difficult to study with airborne or satellite ice-penetrating radar because much of what’s scientifically important happens too close to the surface to be accurately imaged. That has left scientists relying on ground instruments that give only limited coverage, or extracting ice cores — a difficult and time-consuming operation currently impossible to do on other planets.

The new radar technique combines two different radar bandwidths and looks for discrepancies as a way of boosting the resolution. Because the instruments are carried on airplanes or satellites, scientists can quickly survey vast regions of ice.

To test the new technique, the team flew radar surveys over the Devon Ice Cap in the Canadian Arctic where they mapped a slab-like layer of impermeable ice near the surface. Further analysis suggested that the ice layer is redirecting surface melt from the ice cap’s snow-packed surface into water channels downhill. The research was published May, 2023, in the journal The Cryosphere.

According to Kristian Chan, a graduate student at the UT Jackson School of Geosciences who devised the technique, the study’s findings about the ice slab layer could help scientists predict the future of the ice cap and its contribution to sea level rise.

“If you have only relatively thin ice layers then the firn [snow-packed surface layers] has the ability to absorb and retain surface meltwater,” Chan said. “But if these impermeable slabs are widespread then the contribution of surface melt to sea level rise is enhanced.”

Surface melt is normal on ice sheets during summer months. As the top of the previous winter’s snow warms up, meltwater sinks in and refreezes deeper in the snow, forming thin ice layers.

Most of the ice layers on Devon Ice Cap, however, are much thicker than expected, some forming slabs as much as 16 feet thick over several miles. That makes them very effective at redirecting meltwater, which the researchers confirmed when they matched the location of the thickest ice slabs with that of meltwater rivers.

Chan said the findings demonstrate what scientists can accomplish with the new technique.

“We used an airborne radar to find ice slabs on Devon Ice Cap, but the same thing applies for detecting layers with an orbiting radar at ice-covered ‘ocean’ worlds like Jupiter’s moon Europa,” he said.

Chan is part of a UTIG group, led by Senior Research Scientist Don Blankenship, that is developing a radar instrument called REASON, which will launch aboard NASA’s Europa Clipper in 2024. Along with a European Space Agency spacecraft that launched this year, scientists will soon have two ice-penetrating radar instruments investigating Jupiter’s moons Europa and Ganymede. Both radar systems are compatible with Chan’s technique.

With the new technique, scientists will be able to peer into the upper few feet of the icy shells where they might find frozen brine, cryovolcanic remnants or even plume fallout deposits. All are either potential habitats or clues about habitable environments in the subsurface, said coauthor Cyril Grima, a UTIG research associate who is also part of the REASON team.

“Kristian has given us the ability to see things in this hidden part just beneath the surface that is potentially accessible to future landers,” Grima said. “It’s really improved the reconnaissance ability of those radars.”

The research was supported by the NASA Texas Space Grant Consortium at UTIG, and the G. Unger Vetlesen Foundation. UTIG is a research unit of the UT Jackson School of Geosciences.

Devon Island is located in the Canadian Arctic. Its ice cap lies within the marked study area.

CREDIT

University of Texas Institute for Geophysics

The Devon Ice Cap in the Canadian Arctic. The map shows the extent of an ice layer buried among the ice cap’s snow packed surface. Analysis by researchers at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics revealed that the thickest portions of the ice layer can channel meltwater into surface rivers (blue streaks), reducing the ice cap’s ability to hold water.

CREDIT

University of Texas Institute for Geophysics/Kristian Chan

Kristian Chan, a graduate student at The University of Texas at Austin Jackson School of Geosciences, operating an ice-penetrating radar during an aerial survey of an Antarctic ice sheet. Chan developed a technique that boosts the radar’s normally low resolution, allowing it to image hidden features in the ice sheet’s upper layers.

CREDIT

University of Texas Institute for Geophysics/Jamin Greenbaum

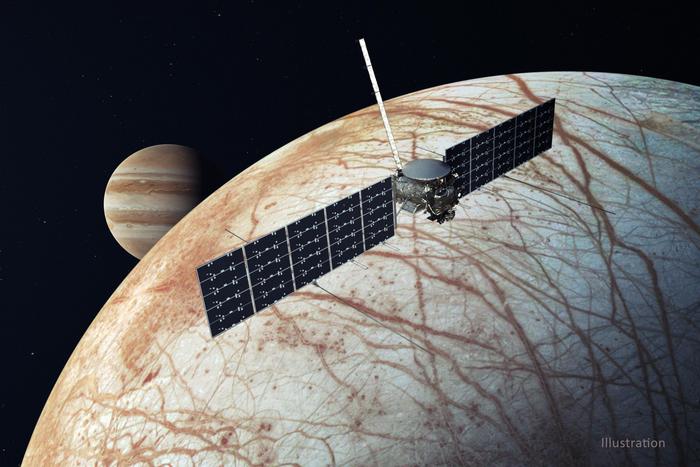

NASA Europa Clipper with REASON

An illustration of NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft approaching Jupiter’s moon Europa. The spacecraft, which is planned to launch in 2024, will carry an ice-penetrating radar instrument developed by scientists at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics.

CREDIT

NASA/JPL-Caltech

JOURNAL

The Cryosphere

METHOD OF RESEARCH

Imaging analysis

SUBJECT OF RESEARCH

Not applicable

ARTICLE TITLE

Spatial characterization of near-surface structure and meltwater runoff conditions across the Devon Ice Cap from dual-frequency radar reflectivity