Merck Prize boosts work on automated air sensor for pandemic pathogens

Emory University chemist Khalid Salaita leads a visionary project

IMAGE: KHALID SALAITA, PROFESSOR OF CHEMISTRY AT EMORY UNIVERSITY, RECEIVED THE 2023 FUTURE INSIGHT PRIZE FROM MERCK KGAA, DARMSTADT, GERMANY. view more

CREDIT: KAY HINTON, EMORY UNIVERSITY

Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany, awarded its 2023 Future Insight Prize to Khalid Salaita, professor of chemistry at Emory University. The award comes with $540,000 to fund the next phase of research into an air sensor that can continuously monitor indoor spaces for pathogens that can cause pandemics.

“I’m extremely thankful to receive the Future Insight Prize as this enables us to continue our path toward an early-warning system for emerging threats,” Sailta says. “Our research sets the stage for fully automated detection of airborne pathogens without human intervention or sample processing.”

The Merck Future Insight Prize recognizes groundbreaking ideas to solve some of the world’s most pressing challenges in health, nutrition and energy. The Salaita lab’s sensor, a rolling micro-motor called “Rolosense,” holds the potential to help mitigate, or even prevent, a pandemic.

“The importance of being prepared is a key lesson from the COVID-19 pandemic,” says Belén Garijo, chair of the executive board and CEO of Merck, a leading science and technology company. “There are many promising collaborations to build an inclusive framework for pandemic preparedness, but we still lack an effective warning system to detect potential threats before it is too late. The pioneering work of Khalid Salaita could help fill this urgent gap in our global defenses.”

Salaita’s lab has already shown that a prototype of the sensor can detect the five variants of COVID-19 that it has tested, along with influenza type A. Theoretically, Rolosense can be programmed to simultaneously screen for a wide group of viral pathogens within a breath sample from an individual or within ambient indoor air.

Within the next five years, the researchers hope to have viable products available to provide convenient, non-invasive, rapid ways to detect airborne viral pathogens. These products may include testing kits for the home and healthcare clinics that screen for an array of viruses within a single test, delivering a result within minutes.

“Our ultimate goal is to develop automated viral air sensors that function similar to smoke detectors,” Salaita says. “These sensors could be located in busy locations like airports, hospitals and schools to continuously monitor aerosolized particles for viruses.”

Salaita is also on the faculty of the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering, a joint program of Georgia Tech and Emory.

Curiosity got the ball rolling on the project around a decade ago.

“We wondered if we could convert chemical energy into mechanical work and make something move,” Salaita recalls. “Ultimately, our goal was to mimic life at the nanoscale. We wanted to make artificial, miniscule motors that match the sophistication and functionality of proteins that move cargo around in cells and perform other functions.”

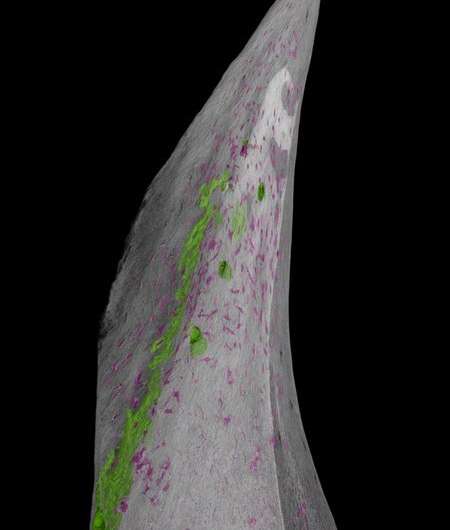

As a graduate student in the Salaita lab, Kevin Yehl had the idea of constructing a DNA-based motor using a micron-sized glass sphere as its “chassis.” Hundreds of DNA strands, or “legs,” were allowed to bind to the sphere. They were then placed on a glass slide coated with the fuel: RNA.

The result was the invention of the first rolling DNA-based motor in 2015. Dubbed the “Rolosense,” the motor was 1,000 times faster than any other synthetic DNA motor. It was so fast that a simple smart phone microscope could capture its motion through video.

Its speed and stability gave the Rolosense potential for real-world applications, such as a tool for medical diagnostics.

Emory graduate students continued to work on refinements of the technologies through the years. Alisina Bazrafshan, who has since graduated and is now a scientist at Illumina, a DNA sequencing company, enhanced the speed and persistence of the DNA-based motors.

When Selma Piranej joined the Salaita lab as a PhD candidate in 2018, she began working on a project to build computer programming logic into the Rolosense. She tapped a well-known reaction in bioengineering to perform the computation and then paired it with the motion of the Rolosense. The computer readout becomes simply “motion” or “no motion.”

These two logic gates of “motion” or “no motion” can be strung together to build more complicated operations, mimicking how regular computer programs build on the logic gates of “zero” or “one.”

Piranej took the project even further by finding a way to pack many different computer operations together and still easily read the output. She simply varied the size and materials of the microscopic spheres that form the chassis for the DNA-based rolling motors. For instance, the spheres can range from three to five microns in diameter and be made of either silica or polystyrene. Each alteration provides slightly different optical properties that can be distinguished through a cell phone microscope.

When the pandemic hit in 2020, the chemists began focusing on using the Rolosense technology to develop an indoor air sensor to detect the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the infectious agent of COVID-19.

The Salaita lab received a $883,000 grant for the project from the National Institutes of Health RADx Radical initiative, which aims to support new, non-traditional approaches for rapid-detection devices that address current gaps in testing for the presence of SARS-CoV-2, as well as potential future pandemic viruses.

Co-investigators on that grant included Gregory Melikian, a professor at Emory School of Medicine, in the Department of Pediatrics’ Division of Infectious Disease; and Yonggang Ke, assistant professor at Emory’s School of Medicine and the Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering.

An additional key collaborator is Primordia Biosystems, a company that specializes in building microfluidic chips that can sample virus-containing aerosols in the air.

Piranej continued to work on the project along with fellow Emory PhD students. She searched through the scientific literature to find an aptamer, a piece of DNA that would bind to a universal spike protein on SARS-CoV-2, sticking to it like Velcro.

Experiments showed that this bind stalls the Rolosense motor, giving the “no motion” readout that signals the presence of SARS-CoV-2. Variants of SARS-CoV-2 share the same spike protein, so the Rolosense is able to detect a range of them.

By adding different aptamers, or binding agents, the researchers have shown they can detect other viruses as well, including influenza type A. Millions of nano-motors are deployed at once via the technology. The motors can be individually programmed so that they each respond only to one specific virus. That means multiple viruses could be simultaneously screened for within one test sample.

“Unlike conventional tests, we don’t have to treat a viral sample in any way to get a result,” Salaita says. “We can do the detection directly from a nasal swab, saliva sample or breath condensate. We don’t have to do any kind of amplification process to enhance the signal. That’s a huge advantage in terms of making the assay more assessable while also preserving ultrasensitive detection.”

The Merck award will support the researchers as they further refine and test the technology.

“Some of the world’s leading experts at testing and validating new COVID diagnostics happen to be on the Emory campus,” Salaita notes. His team will be drawing from this expertise, along with thousands of samples from human COVID-19 infections available in an NIH RADx Radical Diagnostic Core Resources center located at Emory School of Medicine. The samples are used to benchmark and validate the efficacy of a viral assay.

A key challenge in terms of a Rolosense product for home testing or use in a physician’s office is integration of the breath-collection tube with the readout device.

The development of a viral sensor to continuously monitor indoor air also must overcome many chemistry and engineering challenges.

“We’ve shown that our nano-motors can run for at least 24 hours, but we need them to run for days or weeks at a time in an automated system,” Salaita says. “We also have to engineer methods to collect air samples while filtering out enzymes in the atmosphere that chop up DNA. We need to circumvent these enzymes so that they don’t destroy the DNA nano-motors.”

While more development and clinical evaluation is needed, Salaita remains confident that the Rolosense will one day become a useful tool for public health.

“One thing is for certain,” he says. “There is a need for viral-detecting devices for public indoor air spaces as we enter an era when pandemics will likely become more common.”