Antonio Labriola Knew That Marxism Was a Philosophy of Action

Antonio Labriola played a major role in the development of Italian Marxism and inspired the thinking of Antonio Gramsci. Labriola knew that capitalism wouldn’t collapse of its own accord: only a socialist culture of activism could bring about a new society.

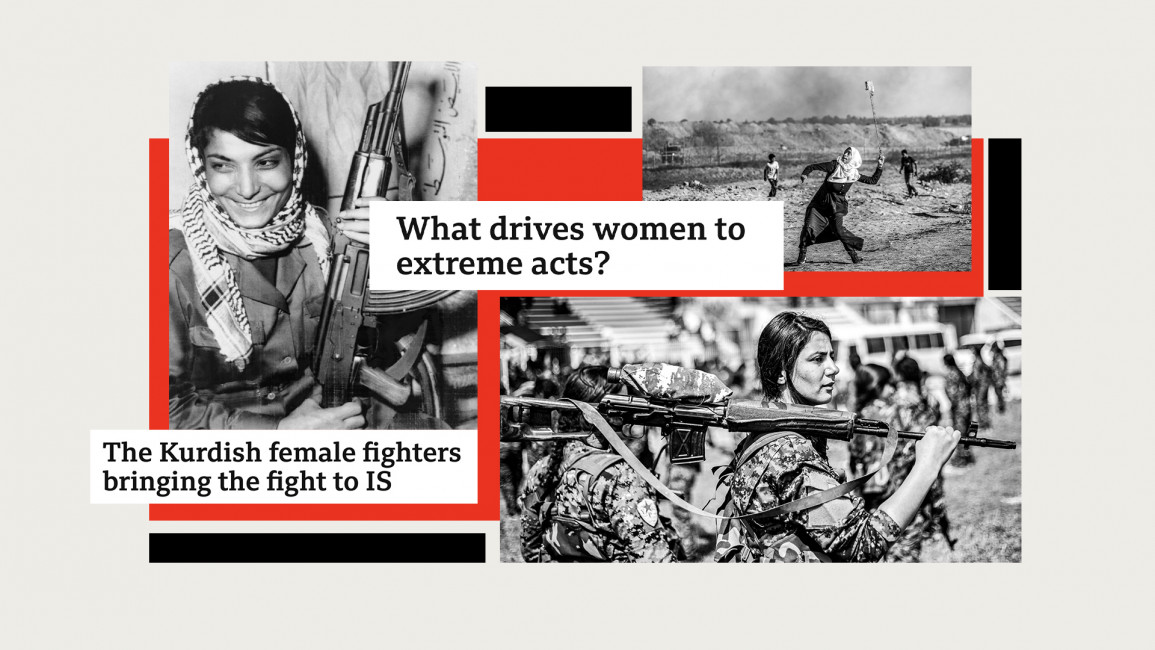

Portrait of Antonio Labriola. (DEA PICTURE LIBRARY / De Agostini Editorial / Getty Images)

BYROBERTO DAINOTTO

07.30.2023

Jacobin

The Italian philosopher Antonio Labriola was one of the key figures in the development of Marxism as a theory during the period after Karl Marx’s death. Breaking with the economic determinism of the Second International, Labriola argued against the reduction of Marxism to what he called “a new scholasticism.”

By reconsidering the relationship between base and superstructure in Marxist theory — rejecting the idea that the former determines the latter in mechanical fashion — he challenged a fatalistic understanding of Marxism that was becoming increasingly prevalent among its supporters and critics alike. For Labriola, an economic crisis like the one that devastated Italy’s banking system in the 1890s could not by itself lead to the collapse of capitalism.

On the other hand, Labriola insisted that we could not reduce Marxism to a form of voluntarism, whereby the ideal aspirations of a class could usher in a new world by sheer force of will. For Labriola, the task of achieving communism meant combining the painstaking work of analyzing the totality of “all present factual conditions” with that of “revolutionizing brains, organizing proletarians.”

Having won the admiration of important Marxist thinkers such as Karl Kautsky, Georgii Plekhanov, and Vladimir Lenin, Labriola fell into comparative obscurity after his death. His distinctive approach to Marxism deserves to be recovered in our own time, as we find once again that a crisis-ridden capitalist system will not collapse of its own accord. Only conscious effort and the development of what Labriola called a “socialist culture” will achieve that.

Philosopher of Praxis

Antonio Gramsci borrowed from Labriola the conception of Marxism as a “philosophy of praxis.” In his prison writings, he lamented that Labriola was now “very little known outside a restricted circle,” barely three decades after his death. Gramsci hoped to “put him back into circulation” as a figure who could challenge a “double revision” of Marxism:

On the one hand, some of its elements have been absorbed by idealistic currents (Croce, Sorel, Bergson, etc., the pragmatists, etc.); on the other, the “official Marxists,” seeking for a “philosophy” that contained Marxism, have found it in modern derivations of vulgar philosophical materialism. Labriola distinguishes himself from both with his claim that Marxism is in itself an independent and original philosophy. Work needs to be done in this direction, continuing and developing Labriola’s position.

Labriola’s understanding of Marxism as “independent” from both idealism and materialism was the result of his systematic knowledge of both philosophical traditions. He was born in 1843 in the provincial Southern town of Cassino, the son of a schoolteacher. His education began at the University of Naples in 1861. As he later wrote to Friedrich Engels, there was “a renaissance of Hegelianism” in Naples that year.Antonio Labriola was one of the key figures in the development of Marxism as a theory during the period after Karl Marx’s death.

Labriola’s mentor Bertrando Spaventa had been exiled from the city in 1849, when the police caught him “speaking ‘Hegelian,’ a language more difficult than Basque,” and seemingly quite threatening to the constituted order. Naples, in those days, was capital of the Kingdom of Two Sicilies under the control of the Spanish Bourbons. In his desire to free the whole of Italy from foreign domination, Spaventa had found in the work of Hegel a philosophy of history in which the ideal “manifests and realizes itself as freedom, and all the labors of history tend towards this result.” In the Hegelian system, he had discovered “the rationality of the revolution,” as he put it, for national independence.

With the successful conclusion of Italy’s Wars of Independence in 1861, Spaventa returned to Naples just in time for Labriola’s matriculation, where he could once more teach his classes on Hegel. This involved talking to his students about an unfolding revolution that was “about to destroy all social inequalities” in the wake of national unification so that “there will be no more noble and plebeian, no bourgeois and proletarian, but only Man.”

Toward Marxism

While Labriola was always proud of what he called “my rigorous Hegelian education,” his enthusiasm for Spaventa’s national revolution was short-lived. A clerical job at the Neapolitan police headquarters, which he needed to support his studies but disliked intensely, had confronted him with the situation of the country’s popular classes.

The experience of their lives trailed far behind the promises of the independent Italian nation and of Hegel’s “ethical State,” understood by Spaventa’s generation as the Aufhebung (transcendence) of social inequalities. The situation was especially dire in the South, which was already caught in the enduring anxiety of postunification Italy that took the name of “the Southern Question.”

Labriola began to move toward supporting increasingly radical positions: restrictions on private property; state intervention in the economy; extension of voting rights; state assistance to the poor and disabled; support for strikes and union demands; popular schooling. As professor of moral philosophy in Rome since 1874, he taught classes on the French Revolution that were open to the general public. This elicited protests from right-wing student organizations and the academic council alike.It was only in Marx that Labriola found a theory that would overcome the limitations of ‘philosophy for its own sake.’

In the meantime, while never giving up on Hegel’s concept of historical becoming as a process of antitheses, Labriola’s attention had shifted toward materialistic philosophical positions. He drew from Ludwig Feuerbach, Johann Fichte, and Baruch Spinoza a philosophy capable of interpreting the material conflicts and contradictions of social reality.

It was only in Marx, however, that Labriola found a theory that would overcome the limitations of “philosophy for its own sake” — philosophy that confines itself to “interpreting the world,” as Marx’s Theses on Feuerbach would have it, instead of changing that world through the unity of thought and praxis. Labriola’s “conversion” to socialism began, or so he wrote to Engels, “between 1879 and 1880.” By the mid-1880s, he was a regular contributor to national and international socialist periodicals, from the German Leipziger Volkszeitung to the British Labour Elector.

When the Czech philosopher Thomas Masaryk declared the existence of a “crisis within Marxism” in 1898, Labriola became a loud voice in the debates that followed, especially when responding to the arguments made by Eduard Bernstein. In a series of articles published in book form as Problems of Socialism, Bernstein felt the need to “revise” Marxist predictions about the imminent and inevitable demise of the capitalist system. As capitalism was not about to disappear, he argued, socialism had to propose reformist policies rather than revolutionary ones.

Firm in his conviction that “critical communism never moralized, predicted, [or] announced,” Labriola used his authority to reaffirm the revolutionary valence of Marxism against “that moron Bernstein,” as he called him. In 1892, he was among the promoters of the first Italian Socialist Party.

Socialist Culture

Labriola’s relationship to the new party was always critical: he once remarked that “a party of critics, which is what the socialist party ought to be, thrives on criticism and self-criticism.” Such criticism reached a climax in 1894 during the insurrections of the Fasci Siciliani, the peasant workers’ leagues of socialist inspiration.

Instead of supporting these movements, the party had concluded that conditions were not mature for a revolt, and that peasants were not industrial proletarians after all. But where could industrial workers be found in the largely agrarian economy of Italy at the time?

Like the Neapolitan Hegelians of the 1860s, Labriola argued, socialist leaders projected their idealist expectations onto real movements “as if they were not in Naples, but in Berlin.” During the harsh police repression decreed by the government of Francesco Crispi, Labriola found it hard to contain his ire: “The party doesn’t want to know about it; it waits for that future transcendental moment when the reactionary mass will face the proletarian mass, and then bang!”

For Labriola, this episode had many theoretical implications. First, it showed that socialism in Italy had to take the reality of the Southern Question into account and learn from the Fasci the importance of achieving strategic coordination between the city and the countryside. Second, one could not reduce socialism to a fatalistic conception of history that meant waiting for a sudden cataclysm.For Labriola, one could not reduce socialism to a fatalistic conception of history that meant waiting for a sudden cataclysm.

Last but not least, it was necessary to thoroughly reconsider the relationship between workers and the party — and by extension, between the masses and the intellectuals, or between theory and praxis. According to Labriola, the party did not possess a “catechism of communism” that workers had to follow. Rather, it was the working masses themselves who were to inform the party’s programs “by changing the modes and schedules of action.”

Although he never embraced a “spontaneist” view of proletarian consciousness, Labriola insisted that party intellectuals could not introduce socialist ideology to the working class from the outside. Instead, they should play the role of mediating between spontaneity and the realization of communism: “Between spontaneous phenomena and the developed consciousness of the proletarian revolution there is a missing link, which is precisely socialist culture.” Labriola devoted his three most important essays to developing such a culture.

The Letter and the Spirit

Written as a preface for the 1895 Italian translation of the Communist Manifesto, his essay “In Memory of the Communist Manifesto” argued for the centrality of socialist culture. If the Manifesto was, as Labriola remarked, “the personal work of Marx and Engels,” the communist movement itself was the real “author of a social form” that the Manifesto represented. The book “has the proletariat as its subject.”

The Manifesto, “small in size, and in style so alien to the rhetorical insinuation of a faith or belief,” had given theoretical substance to “the political action that German communists unraveled in the revolutionary period of 1848–50.” For that very reason, Labriola stressed, its key arguments “no longer constitute for us a set of practical views” — “it merely records as a matter of history something no longer necessary to think of, since we have to deal with the political action of the proletariat which today is before us.”

This was not Labriola’s way of discarding the Manifesto as somewhat passé. On the contrary, he saw it as the best way to remain faithful to its “marrow.” After all, neither Marx nor Engels “pretended to give the code of socialism, the catechism of critical communism, or the handbook of proletarian revolution.” Their intention was, after the fantasies of utopian socialism, to give birth to “critical communism — this is its true name.” The Manifesto was “critical” in the sense that we should recognize its formulations as being provisional and open to the real action of the workers’ movement, interpreting it in the light of changing circumstances.The underlying economic fact of human, material labor is always inseparable from certain forms of consciousness.

Lenin contemplated a Russian translation of this “seriously interesting work” on the Manifesto, and his sister Anne would oblige in 1908. Meanwhile, Labriola was working on his second essay, “Of Historical Materialism: A Preliminary Explication” (1896). Once again, we find here the idea that critical communism is not “the intellectual vision of a grand plan or design” but rather “the objective theory of social revolutions.” According to Labriola, its theory is “a plagiarism of the things it explains.”

However, such “plagiarism” did not entail mere descriptive empiricism or a contemplative view of reality. To clarify this point, Labriola tackled the problem of base and superstructure:

For our doctrine the problem is not to retranslate into economic categories all the complicated manifestations of history. It is a matter of explaining in the last instance (Engels) every historical fact by way of the underlying economic structure (Marx): to do that, analysis, reduction, and then mediation and composition are needed.

This meant that, within the totality of social relations, the interdependence of base and superstructure unfolds through historical processes of mediations:

There is no historical fact which does not repeat its origin from the conditions of the underlying economic structure; but there is no historical fact which is not preceded, accompanied and followed by certain forms of consciousness.

We might recall here a famous remark that Marx made about the distinctive nature of human labor: “What distinguishes the worst architect from the best of bees is this, that the architect raises his structure in imagination before he erects it in reality.” The underlying economic fact of human, material labor is always inseparable from certain forms of consciousness.

For Labriola, this meant in practical terms that theory without political action is no more than idle speculation, while political action without theory is but the myth of “spontaneous anarchy,” which always runs the risk of transforming rebel groups into “automatic instruments of reaction.”

Labriola’s third essay came in the form of letters to Georges Sorel that were collected under the title “Discussing Socialism and Philosophy” (1898). He conceptualized the interrelation of theory and action in a formula as “the philosophy of praxis,” which he describes as “the marrow of historical materialism . . . the philosophy immanent to the things about which it philosophizes.”

The formula had certain antecedents on the Hegelian left (August von Cieszkowski, Moses Hess), but Labriola meant it in an original way. Neither idealism nor materialism, neither positivism nor economism, the philosophy of praxis is a total “Lebens-und-Weltanschauung,” or “general conception of life and the world.” It is the “self-critical” analysis of historical mediations that at the same time explains and strives to transform the totality of social relations.

As such, it is articulated in three domains:

(a) the sphere of philosophy, as the general theory of the history and praxis of man in society; (b) the sphere of the critique of economics, as the science of that particular historical stage constituted by the society organized on capital; (c) the sphere of politics, as the theory of the organization of the workers’ movement aimed at the construction of socialism.

Labriola’s Legacy

Having been such an important, looming presence in the life of Italian and international Marxism at the turn of the nineteenth century, Labriola’s name is barely recognized today. He is often confused with the socialist politician Arturo Labriola, of whom he had a contemptuous view: “nothing to do with me and cannot even understand the books on which he writes nonsense.”Having been such an important, looming presence in the life of Marxism at the turn of the nineteenth century, Labriola’s name is barely recognized today.

One cause of Labriola’s oblivion was none other than his most famous student, the philosopher Benedetto Croce — or “la mia croce,” my punishment, as Labriola called him. When Labriola died on February 12, 1904, the Socialist Party, holding steady on its revisionist course, did its best to forget his name. “We will return to his writings in the moments of idleness that militant life allows,” concluded the eulogy of party leader Filippo Turati.

The liberal Croce, on the other hand, was eager to return to Labriola’s writings now that the author could no longer reply. In his work Historical Materialism and Marxist Economy, Croce presented Labriola as offering “the most thorough and deep treatment” of Marxism, before going on to argue that he ultimately failed to provide communism with a coherent philosophy. With Labriola, Marxism was “dead,” according to Croce — a judgement he pronounced in the role of Italian philosophy’s “secular Pope,” as Gramsci dubbed him.

When the Italian Communist Party began reconstructing a Marxist culture from the ruins of fascism in the late 1940s, it claimed to be returning not to Labriola but to Gramsci’s “anti-Croce.” True, Gramsci had indeed “put back into circulation” quite a few of Labriola’s concepts, from the need for a united front between city and countryside in his writings on the Southern Question, to the idea of Marxism as a “philosophy of praxis” and the dialectics of “critical communism” as a process of continuous verification and falsification between theory and action.

Behind those pointers, however, the name of Labriola long remained unheard, unfelt, unseen. It is only in the twenty-first century that Labriola’s thought has begun resurfacing, culminating in the prestigious National Edition of his works that is now underway in Italy.

As capitalism keeps escaping the self-inflicted disasters of financial crises and unprecedented exploitation of resources, both human and natural, the work of an eminent nineteenth-century Marxist seems timely. That work can still make a valuable contribution in clarifying the direction that theory, as the “plagiarism of things,” ought to follow in the organization of a movement aimed at the construction of socialism.

CONTRIBUTORS

Roberto Dainotto is a professor of literature at Duke University. He is currently working on an intellectual biography of Antonio Labriola.