In emergency rooms, marginalized patients more likely to be skipped in line

In most U.S. emergency departments (ED), patients are admitted in an order based on both the urgency of their condition and when they arrived. But in a new study, Yale researchers found that nearly 29% of ED patients are jumped in line, with those from marginalized groups—including lower-income patients, non-white patients, and non-English speakers—more likely to be cut by others.

This phenomenon, the researchers say, can affect patient outcomes and highlights the need for standardized procedures.

The study was published in JAMA Network Open.

Typically, when a patient enters an emergency department—whether they walked in or were transported by ambulance—they're given an initial assessment by a triage team and assigned a score based on their medical need. That score comes from the emergency severity index, which ranges from one to five. A score of "one" is assigned to the most urgent events, like cardiac arrest; a "five" is the least urgent, encompassing needs like prescription refills.

According to this system, if two patients come in at the same time, the one with the more severe score will be treated first. If two patients have the same score, the person who arrived earlier will be treated first.

But it doesn't always work that way. In an analysis of electronic health record data from two high-volume emergency departments between July 2017 and February 2020, the researchers found that 28.8% of patients were passed over at least once by patients with a lower severity score or later arriving patients with the same severity score.

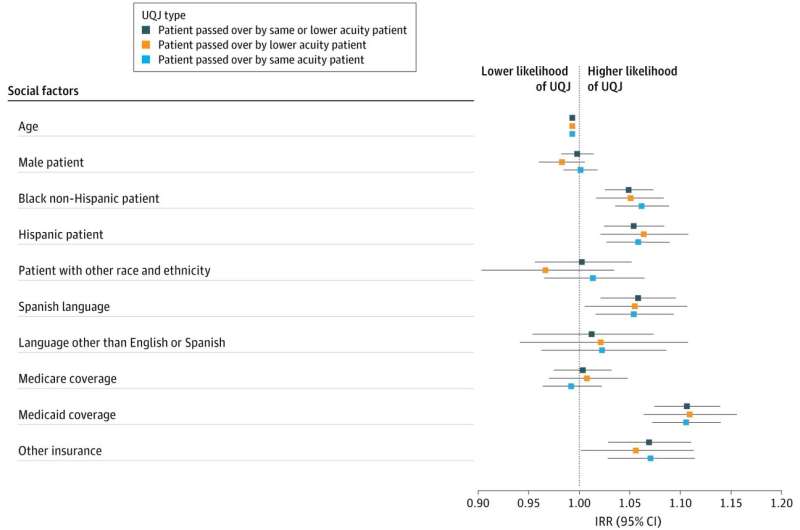

Patients with Medicaid as their primary insurance were more likely to be queue-jumped than those with private insurance. Similarly, patients who were Black or Hispanic were more likely to be passed over than white patients, and Spanish-speaking patients were more likely to be queue-jumped by English-speaking patients.

"Some of these queue jumps may, in fact, be appropriate, as patients do get sicker and their severity levels do change," said Dr. Rohit Sangal, assistant professor of emergency medicine at Yale School of Medicine and lead author of the study. "But not all of these jumps are justified."

The researchers also found that patients who were jumped over were more likely to leave before their care was completed, and more likely to be placed in a hallway rather than a room.

"That limits how well we can perform an exam," said Sangal. "We have to ask sensitive questions, which is harder to do with people walking by. And doing bedside procedures in a way that maintains a patient's privacy is very difficult if not impossible."

Classism and racism may contribute to the disparities uncovered in the study, said the researchers. And while some discrimination may emerge during interpersonal interactions in emergency departments, they said, looking at how it emerges across different levels of the health care system will be essential for finding effective solutions.

"There may be an assumption that patients are being discriminated against by whoever's doing the triage," said Dr. Hazar Khidir, an instructor of emergency medicine at Yale School of Medicine and co-author of the study. "But the key here is, this is a structural issue."

For instance, Khidir said, marginalized patients may have less access to outpatient care generally and, therefore, less information in their medical records. That could lead emergency department triage teams to underestimate the severity of their illness. Additionally, patients who do have regular outpatient care may benefit from their provider's advocacy and get moved up the queue.

Addressing these different levels of injustice will require a comprehensive set of interventions, said the researchers, which could include new guidelines for queueing, different approaches to triage, and diversifying the medical workforce so it better mirrors the patient population.

In the study, the researchers found no disparity in queue jumping when they assessed patients with the most severe scores, those experiencing stroke or trauma, for example.

"In those cases, there are clear protocols for what we do regarding treatment," Sangal said. "And that this disparity goes away with this group of patients speaks to how well-defined protocols may help close these gaps."

Going forward, it will be important to reassess queuing and patient outcomes after steps have been taken to address the problem, the researchers say. They suggest that an approach like the one used in this study—evaluating large sets of nuanced data with input from clinicians who experience the challenges firsthand—will help researchers evaluate progress.

"After emergency departments make changes, we can then measure if anything has improved," said Lesley Meng, assistant professor of operations management at Yale School of Management and co-author of the study. "If not, we can tweak the approach. But if it is, then we can disseminate the intervention to other medical centers and share best practices more broadly."

More information: Rohit B. Sangal et al, Sociodemographic Disparities in Queue Jumping for Emergency Department Care, JAMA Network Open (2023). DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.26338