Surprisingly deadly summer for Lake Tahoe bears: 20 killed, 18 hurt in vehicle collisions

Twenty bears killed and almost 20 more injured—it's been a uniquely dangerous summer for Lake Tahoe's bear population, with more hit by vehicles from late July to mid-August "than we've ever had at that time," said Ann Bryant of the Bear League.

"There were days when we had four bears in one day that were hit," said Bryant, executive director of the organization dedicated to promoting the safety of bears in the Tahoe region.

As humans continue to encroach on wilderness lands like those near Lake Tahoe, incidents of wildlife being injured or killed by vehicles have increased. It's even "fairly common," Bryant said, for bears to be struck by vehicles in the fall when the animals are in hyperphagia—consuming as much food as possible before hibernation.

"They're out cruising and going back and forth across the roads and heading down to the lake and then back up into the forest," Bryant said. "That's a lot of hours to be out on the road. We kind of expect it then."

But this summer, Bryant and her organization have received reports of an inordinate number of bears being struck by vehicles.

Officials with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife have also noticed the trend.

"We've definitely seen an uptick in vehicle-bear collisions this summer," said Sarinah Simons, human-bear management specialist for the California State Parks' Sierra District.

Pinpointing the total number of collisions is difficult because many incidents go unreported, she said.

"Sometimes there's a collision and the animal walks off and is OK, or it might have a little bit of a limp," Simons said. "Bears heal relatively quickly and relatively well."

But Simons noted that "probably more than half" of collisions are fatal.

From mid-July through Monday, Bryant said, at least 20 bears had been fatally struck by vehicles. At least 18 other bears were walking around with injuries.

Their chances of surviving a collision "depend on the bear," Simons said, including how old the animal is.

In some incidents, drivers will see and stop for a mother bear who crosses a road but hit a cub that is trailing her.

"The little cubs of the year and sometimes the yearlings," cubs around 18 months old, "it's harder for them to recover from collisions like that," Simons said.

Bryant recalled a poignant incident earlier this summer when a mother bear was seen carrying the body of a cub that had been fatally hit not far from the west shore of Lake Tahoe.

Bear League staffers eventually managed to scare the mother away from the cub long enough for the cub's body to be retrieved.

What's behind the jump in collisions? Increased tourism to Tahoe could be playing a role, Simons said.

"Every year in Tahoe, we get more and more visitation," Simons said, "and more visitation means more traffic and more people on the road."

More people means more food sources near the beaches, where people gather, and in neighborhoods—areas bears need to cross roads to access.

"I think a lot of it is the tourists that just don't know that ... they need to be really aware," Bryant said, and keep their eyes on the road instead of the scenery.

In a release from earlier in the summer regarding vehicle collisions with bears, the Department of Fish and Wildlife urged drivers to maintain vigilance while on the roadways.

"Follow speed limits, watch for signs posted in known wildlife collision areas, and most importantly SLOW DOWN," the department said.

The department also advised drivers that bears are often trailed by their young.

"If you see a bear on the roadway, slow down and scan for other bears or hazards," the department said.

Bryant echoed many of those suggestions but still expressed bewilderment over the large number of recent collisions.

"You know, how can you miss seeing a bear?" she said. "I mean, they're big."

2023 Los Angeles Times.

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Bear–human coexistence reconsidered

The media uproar over wolf attacks on livestock in Switzerland and a bear attack in Italy show how charged the issue of large carnivores and humans coexisting in Europe is. ETH Zurich researcher Paula Mayer has now created a participatory model to help facilitate human-bear coexistence using the example of the Apennine brown bear.

Less than two hours' drive from the metropolis of Rome, bears still roam the woods. The Marsican or Apennine brown bears, a subspecies of the European brown bear, currently number about 70. For now. Thanks to improved protection, educational work and measures to prevent the damage these animals sometimes cause, this population has survived and has even increased slightly in recent times.

But the endangered bears still perish on highways or die from poison bait laid out by truffle hunters for their competitors' truffle-sniffing dogs. And not everywhere in their home range do people sympathize with the large carnivores.

Map identifies coexistence areas

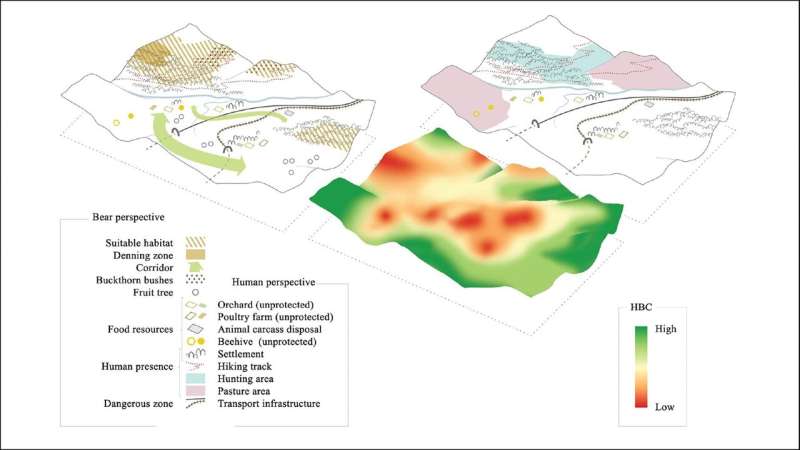

For this reason, Paula Mayer came up with the idea of creating a model for the coexistence of humans and bears in the Abruzzo, Lazio and Molise National Park region and plotting it on a map in her Master's thesis.

This map is intended to support those involved at the local level—authorities, conservationists, farmers and tourism specialists—in identifying areas and measures that should be prioritized to promote human-bear coexistence.

"This project is an attempt to take a rational look at the landscape and figure out where and under what circumstances humans and large carnivores successfully coexist and where they don't," Mayer explains. Her supervisor, ETH Zurich Professor Adrienne Grêt-Régamey, encouraged Mayer to turn the methodology of her work into a scientific publication, which has just been published in the Journal for Nature Conservation.

Twenty-one municipalities evaluated

Mayer used her model to create maps for a total of 21 municipalities located in and around the Abruzzo National Park. As examples, she selected three municipalities and analyzed them in more detail.

While one municipality has a positive attitude towards the large carnivores, making bear-human coexistence very likely possible there, peaceful coexistence is rather unlikely in another of the municipalities surveyed. "It depends on things like whether the people in the municipality have been in contact with bears for a long time, or whether they know these animals only from hearsay." Mayer says she was surprised that in some cases municipalities just a few kilometers apart often had different opinions about the bears. This is mostly because of individual opinion makers who spread (false) information, she explains.

The question of coexistence also depends on whether the people in a given municipality rely on their own agricultural products or earn their living in tourism or away from home. "Tourism-reliant municipalities even stand to benefit from the bears, since wildlife tourism is booming in the Abruzzo National Park." Money is also being invested to make the local waste disposal, fruit crops and livestock bear-proof. The situation is different in rural municipalities, where preventive protection measures often lag behind. "If you own only ten sheep and a bear kills one of them, you feel your livelihood is threatened," Mayer says.

A global problem

Mayer believes that the "large carnivore problem" is the same everywhere. She says it's mostly an urban-rural conflict charged with emotion, and with a lot of symbolism projected onto the animals. "But it's more about interpersonal issues and control; the wild animals only serve a symbolic function."

The question, Mayer adds, is what measures are needed on the ground so that bear-human coexistence can succeed. One important factor that emerged from interviews with locals is that they want government compensation payments to be disbursed more quickly and with less red tape—or indeed for the government to actually make such payments in the first place. "Some people are angry because they've never been compensated for any damage caused by individual bears, despite promises to the contrary."

A practical tool

The model and generated coexistence maps constitute a practical tool, for example for examining how bear-human coexistence in the landscape changes over time. It can also be used to test whether measures are effective at the local level.

"If the model produces a map that shows areas of low coexistence despite measures like fences to protect beehives from bears, you can infer how effective a measure is—and whether other measures might be better for promoting coexistence in that location," Mayer says. "That's something we can assess very well—or even predict—with the model."

And it doesn't take a powerful mainframe computer to generate these maps either: the current maps were made on Mayer's laptop.

Network with many nodes

Mayer used a Bayesian network to approach this multi-layered problem. Such networks operate with conditional probabilities and can take into account and connect a variety of different factors. The model approach considers factors that both represent the human perspective and reflect the needs of the bears. These variables can be updated with explicit local information. To obtain this information, she worked with experts from nature conservation, tourism and research and conducted interviews with local people.

The bears' perspective is represented by factors such as suitable habitats, migration corridors and whether attractive human-made food resources are present. The latter include waste disposal facilities, orchards and livestock that aren't bear-proof. This affects the probability of bears appearing in and around settlements.

The model also considers threats to bears, such as unfenced sections of roads and railways or areas with a lot of tourist disturbance. The human perspective is influenced by network nodes such as different types of agriculture, hunting and truffle collecting as well as by local policies, damage compensation, knowledge and emotions regarding the bears.

To generate a map, the model links all these nodes and factors them in. This map shows the areas where human-bear coexistence works best. These are zones where people's tolerance is high and living conditions for bears are good. But it also shows areas where conditions are worse. "This model lends itself very well to mapping the complex web of interdependencies that underlie the coexistence of large carnivores and humans," Mayer says.

Moreover, the network nodes can be expanded as needed: in other contexts, nodes can be removed and replaced or new ones added. This makes it relatively easy to adapt and tailor the model to other cases—for example, to other regions or animal species such as wolves. "It is crucial to work with the people on the ground to incorporate the specific information from the local context into the model," explains the researcher.

Mayer came across this topic during an internship that was part of her Environmental Sciences study program at ETH Zurich. She worked for the conservation organization Rewilding Apennines in a project that aims to promote the coexistence of humans and the Marsican brown bear and other wildlife in the Central Apennines.

More information: Paula Mayer et al, Mapping human- and bear-centered perspectives on coexistence using a participatory Bayesian framework, Journal for Nature Conservation (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.jnc.2023.126387\

Provided by ETH Zurich Competition for food? Jaw analyses show what cave bears and brown bears ate