Michael McDonald

Mon, August 28, 2023

(Bloomberg) -- The party of Guatemala’s President-elect Bernardo Arévalo was suspended by a government agency on Monday, adding uncertainty to a process marred by legal disputes and accusations of foul play.

The Citizens’ Registry, an office within the country’s electoral authority, provisionally suspended Arévalo’s Semilla party, according to a copy of the ruling seen by Bloomberg News. Party lawmaker Samuel Perez said in reply to written questions that he and his colleagues had been notified of the decision.

The Registry recommended the suspension pending an ongoing investigation by prosecutors into whether rules were breached during the formation of the party in 2018.

The electoral authority on Monday formally confirmed Arévalo as the winner of the Aug. 20 vote, meaning he’s due to take office in January. If the ruling that dissolves his party stands, it would potentially undermine his ability to govern since Semilla legislators might have to sit as independents, making them ineligible for some legislative committees.

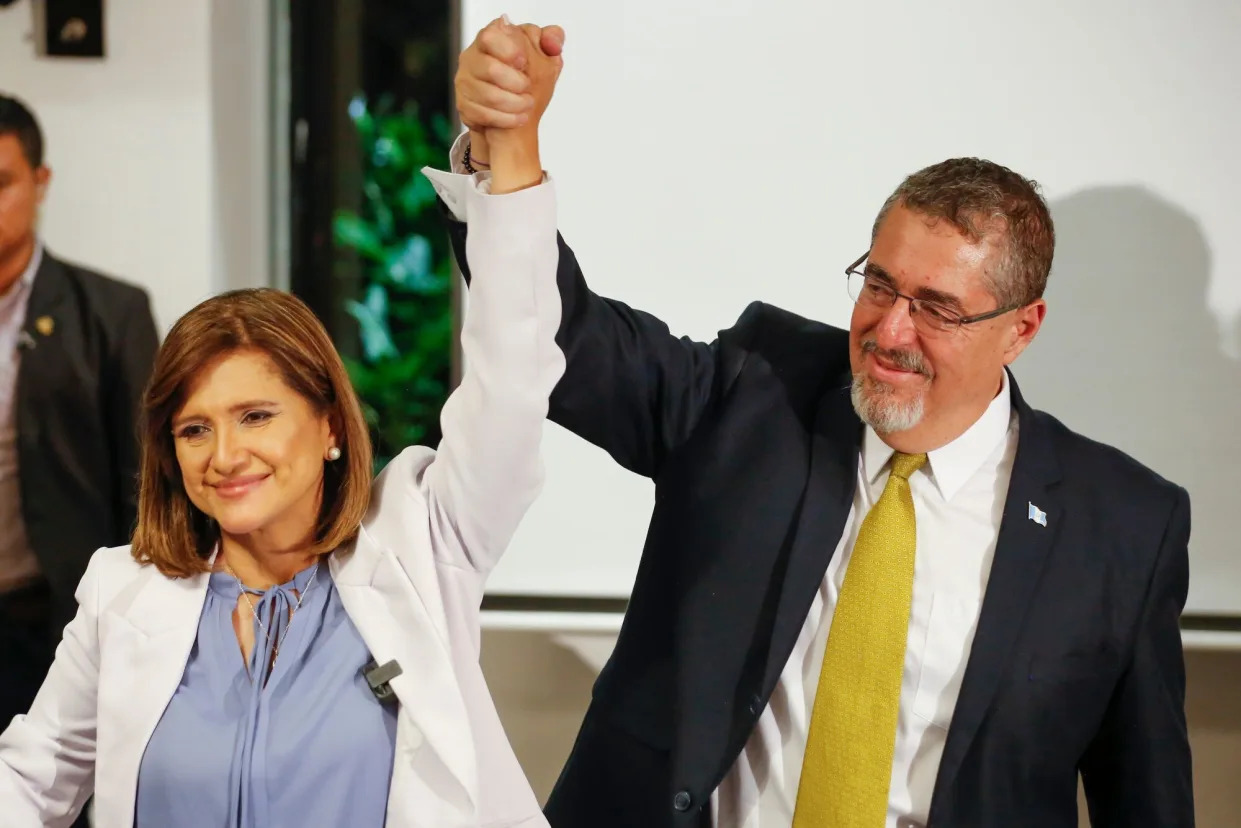

Arévalo, 64, remained in contention during the election campaign amid repeated attempts to overturn the result, which led US officials to warn that democracy was under threat in the country. He has pledged to weed out corruption and increase oversight of government spending in the graft-ridden nation.

Perez said that the ruling should not affect Arévalo’s inauguration.

Irma Pelencia, the head magistrate of the electoral authority, told reporters on Monday that she and her colleagues cannot comment on the registry’s ruling. However, the citizens’ registry is subordinate to electoral authority magistrates, she said.

SONIA PÉREZ D. and MEGAN JANETSKY

Updated Mon, August 28, 2023

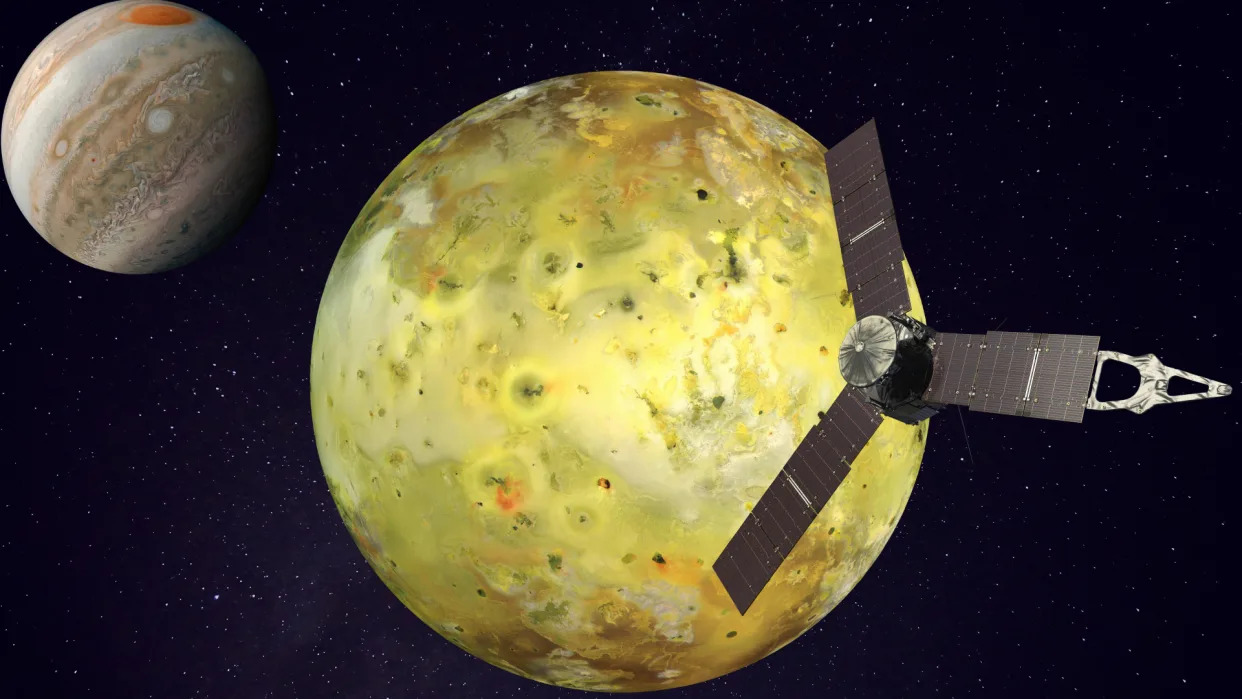

Presidential candidate Bernardo Arevalo listens to a question during a press conference after preliminary results showed him the victor in a presidential run-off election in Guatemala City, Sunday, Aug. 20, 2023.

GUATEMALA CITY (AP) — Guatemala’s Supreme Electoral Tribunal on Monday declared progressive Bernardo Arévalo the winner of the country’s presidential election, shortly after another government body suspended his Seed Movement party.

No Guatemalan officials have explained exactly what the suspension by the electoral registry will mean for the president elect, who is to take office on Jan. 14, or for the Seed Movement lawmakers elected in the first round of voting in June.

But late Monday Arévalo called the registry's ruling legally void and said his party would appeal it.

“As of this moment, no one can stop me from taking office on Jan. 14,” he told a news conference.

The electoral registry's ruling arose from an investigation into the Seed Movement by Guatemala’s attorney general’s office for alleged irregularities in the gathering of signatures for its formation as a party.

If the Seed Party appeals the ruling, as promised, the case will be taken to the Supreme Electoral Tribunal.

The announcements come after one of the most tumultuous elections in the Central American nation’s recent history, which has put to test Guatemala's democracy.

At a time when Guatemalans, hungry for change, have grown disillusioned with endemic corruption, Arévalo and other opponents of the country’s elite faced waves of judicial attacks in an attempt to knock them out of the race.

Arévalo, the little-known son of a former president, shocked much of the country by emerging as a frontrunner after the first round of presidential voting. He failed to get enough support to win outright and headed to a runoff vote against former first lady Sandra Torres. His rise came after a handful of other candidates were disqualified.

Arévalo rapidly gained support as he posed a threat to the country’s elite, campaigning on social progress and railing against corruption.

"This message generated, aroused hope, mobilized people who were fed up with corruption,” told the AP in a June interview.

He easily beat Torres in the Aug. 20 presidential runoff. According to the official count, the progressive candidate obtained 60.9% of the valid votes cast against 37.2% for the right-wing Torres. The party also won 23 seats in the 160-seat Congress.

His win has been the source of a legal back-and-forth between various governmental entities and courts, some staffed with officials that have been sanctioned by the United States on charges of corruption. He has faced allegations of voter fraud by Torres, legal challenges and more.

Eight days after the runoff, Torres still hasn’t conceded defeat and outgoing President Alejandro Giammattei hasn’t said anything about the latest developments.

Guatemala's Supreme Electoral Tribunal outranks the electoral registry so the victory by Arévalo and the seats won in parliament by Seed Movement lawmakers in the first round elections appear confirmed. But the impact of the suspension of their party would have is unclear and whether it could be used somehow against Arévalo's taking office.

“It's obviously another attempt to subvert Semilla's (the Seed Movement's) path to power," said Alex Papadovassilakis, a Guatemala-based investigator for InSight Crime focused on crime and corruption. “I think we're entering uncharted waters.”

Arrest warrants for electoral officials and raids to the party’s headquarters, have also caused concern in the international community and among Guatemalans.

Earlier this week, Organization of American States’ human rights commission asked that Guatemala provide protection for Arévalo after reports emerged of a possible plot to kill him.

Arévalo’s victory has left much of the country’s political establishment reeling while supporters of Arévalo have held protests against attempts to thwart his taking office.

United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres expressed concern about the attempts to undermine the results of Guatemala’s presidential election, a U.N. spokeswoman said earlier.

The 64-year-old son of former President Juan José Arévalo was born in Uruguay, where his father was in exile following the ouster in a 1954 CIA-backed coup of his successor President Jacobo Árbenz, whom the U.S. saw as a threat during the Cold War.