The United Auto Workers are engaged in high-stakes labor negotiations that could lead to the union’s first simultaneous strike against all of Detroit’s Big Three automakers: General Motors, Ford and Stellantis, the company that owns Chrysler.

After decades of making concessions to their employers, the union’s demands for pay increases and better benefits exceed what some automotive industry executives say are reasonable. Unless the two sides reach an agreement by midnight on Sept. 14, 2023, 97% of the 150,000 UAW members employed by the three companies have authorized their leaders to call a strike.

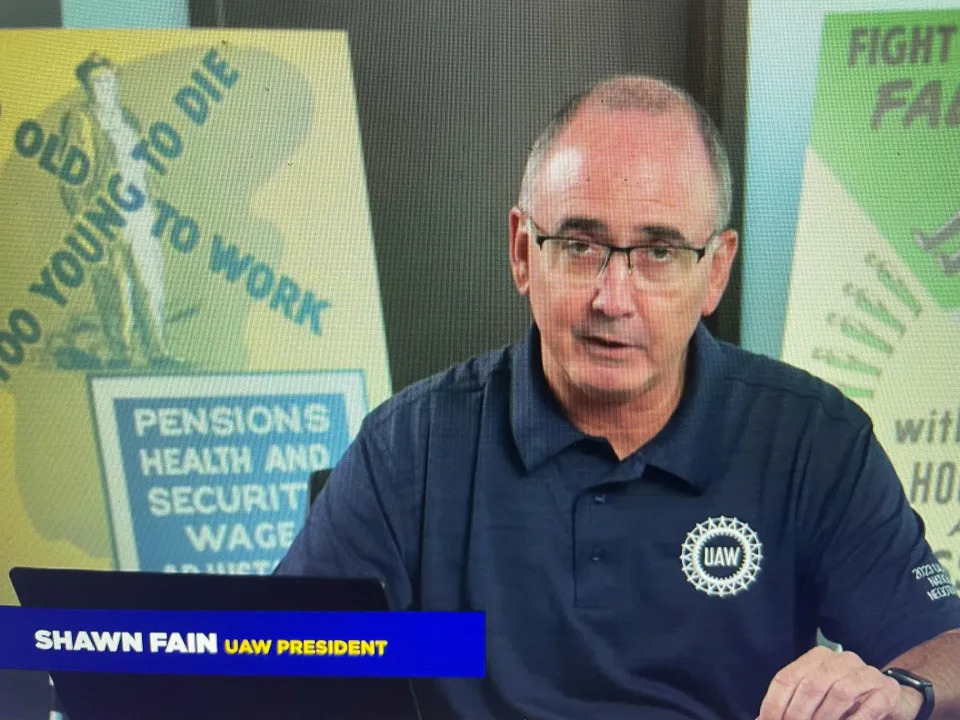

It would be the industry’s first walkout since a monthlong GM strike in 2019. UAW President Shawn Fain, elected in March 2023, and other new UAW leaders have a decidedly more militant approach than their recent predecessors – some of whom landed in prison after being convicted of embezzling union funds.

As a labor and business scholar who has studied the history of UAW collective bargaining with the Detroit Three, I believe that whether or not the union does hold a strike against one or more of the automakers in the near future, it would benefit from heeding some lessons from its own past. In particular, it should consider the legacy of Walter Reuther, the labor leader who served as the UAW’s president from 1946 until his death in 1970. By balancing his vision and aspirations with pragmatism, Reuther showed that bold labor leaders can score big wins.

Miscalculations can be costly for workers

Although strikes can lead to victories, workers can end up worse off than they would have been had they not walked off the job. People who go on strike can even end up unemployed. That means unions must carefully calculate whether the risk of going on strike is worth taking.

Strikes that fail to meet their objectives, often due to miscalculations by unions of their power to win concessions from employers, litter U.S. labor history.

These failures were particularly common in the 1980s and 1990s, as companies and other employers demanded concessions and replaced workers during and after strikes.

That trend began with the ill-fated strike by 11,500 air traffic controllers in August 1981. Soon after Robert E. Poli assumed its presidency, the Professional Air Traffic Controllers went on strike. The union, known as PATCO, underestimated President Ronald Reagan’s resolve and overestimated its members own irreplaceability.

Reagan’s swift termination of the striking workers and his success in replacing them with new employees destroyed PATCO and normalized the replacement of strikers by employers.

More strikes would lead to similar failures, including one by Hormel meatpackers in Austin, Minnesota, which lasted 13 months starting in August 1985. A 15-month walkout by International Paper workers at several plants in 1987 and 1988 was also disastrous for the strikers.

In both cases, the local union leaders launched prolonged strikes over corporate demands for wage cuts and other givebacks to compete with their lower-cost nonunion rivals. The unions underestimated management’s resolve and proved incapable of conducting effective publicity campaigns or applying other kinds of pressure to combat the companies.

The companies fired strikers, replacing them permanently with other workers.

Lessons from Walter Reuther

A UAW strike today could also miss the mark, given that Detroit’s Big Three face relentless competition from foreign automakers, along with Tesla and newer U.S.-based companies that only manufacture electric vehicles. What’s more, GM, Ford and Stellantis are spending billions to phase in large-scale EV production.

Here are three lessons that I believe Fain and other UAW leaders should draw from Reuther’s legacy:

1: Articulate a clear vision

In 1945, a year before he became the UAW’s longest-serving president, Reuther led 320,000 GM workers on a 113-day strike that ended with pay raises, overtime compensation and paid vacation days. The way he spelled out the philosophy behind the strike helped inspire the workers’ confidence.

After autoworkers had done their part to win World War II, Reuther later said, they struck for “the right of a worker to share – not as a matter of collective bargaining muscle, but as a matter of right – to share in the fruits of advancing technology.”

Like many of Reuther’s poignant comments, those words still resonate today as technology upends the automotive industry.

2: Recognize the limits of what’s within reach

In 1950, following a 102-day strike by 95,000 Chrysler workers, Reuther negotiated breakthrough agreements with GM, Ford and Chrysler known collectively as the “Treaty of Detroit.” The pacts included big increases in wages, health care benefits and retirement pensions.

But pragmatism tempered Reuther’s determination to achieve all the union’s objectives. He knew when to strike and when to settle. Reuther understood the union’s capacity to hold a strike and how much harm it could inflict upon a company before the costs became prohibitive for both sides.

He used strikes strategically, knew which company to target – and when. Reuther knew to settle when the union’s ability to push a company for further concessions had reached a ceiling beyond which the losses on both sides exceed any possible future gains.

And he realized that worker priorities that could not be won in a current round of bargaining could be pushed to the next. Reuther understood that autoworkers and their employers depended on each other to make progress.

3: Balance competing interests

Reuther also understood the limits of the UAW’s power, and he knew how to bargain for a contract that both autoworkers and automotive executives could accept.

In a speech he made on Labor Day in 1958, Reuther defined labor’s task as “to cooperate in creating and sharing abundance … [which] requires working out a proper balance between competing equities of workers, stockholders and consumers.”

New reality

Reuther’s reign coincided with Detroit’s dominance. At least 85% of the vehicles U.S. drivers bought through the mid-1960s were made by the Big Three automakers.

Those companies’ total U.S. market share is less than half of that now – a total of about 41%, with 16% for GM, 14% for Ford and 11% for Stellantis.

Autoworkers also wield less power today than they did back then.

UAW membership has dwindled to fewer than 400,000 members, including the 150,0000 people directly employed by GM, Ford and Stellantis who may soon go on strike. Some 1.5 million workers belonged to the union at its 1979 peak. Unions represent only 16% of the workers employed in the U.S. motor vehicle and parts industry in 2022, down from nearly 60% in 1983.

GM, Ford and Stellantis have vowed to resist any demands they deem unreasonable. Both labor and management could incur potentially substantial losses in a strike, which would compound over time. Even a 10-day strike could cause an estimated US$5 billion in economic damage or more, according to the Anderson Economic Group consulting firm.

I believe that the path to a settlement requires understanding how an avoidable strike would put both sides behind, while their competitors move forward.

And I keep on wondering what Walter Reuther would do – and whether Shawn Fain is doing that too.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. If you found it interesting, you could subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

It was written by: Marick Masters, Wayne State University.

Read more:

Marick Masters is the director of Labor@Wayne at Wayne State University. The university has received contributions from the joint training funds from the UAW and the Big Three to support education in labor-management relations. These contributions were used strictly for this purpose.