ICYMI

Europe’s biggest oil company quietly shelves radical plan to shrink carbon footprint

LONDON - Six months after becoming the chief executive at Shell, Mr Wael Sawan quietly ended the world’s biggest corporate plan to develop carbon offsets, the environmental projects designed to counteract the warming effects of carbon dioxide missions.

In an all-day investor event in June, Mr Sawan laid out an updated strategy for the European oil major that included cutting costs and doubling down on profit drivers such as oil and gas.

As important was what he omitted: Any mention of the company’s prior commitment to spend up to US$100 million (S$135 million) a year to build a pipeline of carbon credits, part of a promise to zero out its emissions by 2050.

Those goals for the offsets programme have been retired, the company confirmed, along with the plan to harvest a whopping 120 million carbon credits annually by the end of the decade from projects that sequester carbon with trees, grasses or other natural resources, many of which Shell would develop itself.

That would have accounted for 10 per cent of the company’s emissions. It has not made public any new targets for developing offsets or specified how it now plans to deliver on its future climate commitments.

The pullback reflects both Mr Sawan’s renewed commitment to the oil and gas business that generates most of Shell’s profits, and an admission that the prior goals were simply unattainable.

Over the past two years, Shell barely made a dent.

It spent US$95 million, less than half of its initial budget, to build or invest in a portfolio of carbon projects from Western Africa to the Brazilian Amazon to Australian farmlands. They have generated few if any offsets, and Shell has struggled to find projects that meet its standards for quality.

It is a newly damning indictment of offsets, which have become an important if controversial “climate solution” for most big companies: Bloomberg New Energy Finance estimates the voluntary carbon market, which totals around US$2 billion today, could grow as high as US$950 billion by 2037.

Ms Flora Ji, a 17-year Shell veteran, has run the company’s nature-based solutions operations since 2021. In an interview before Mr Sawan scrapped the official 120 million-offsets-per-year target, she said everyone knew it was a big number, a reach.

Meanwhile, the carbon market had not expanded rapidly enough to meet rising demand, she said. “It didn’t have that kind of huge, exponential growth we expected.”

Offsets, even of the highest quality, were never intended to be the only solution for Shell or anyone else. The Science Based Targets initiative, a UN-backed agency that evaluates companies’ net-zero goals, recommends offsetting no more than 10 per cent of emissions, and then only after making every other possible cut.

Ms Ji said that has been Shell’s long-term approach, first to avoid emissions, then to reduce and finally to offset.

“Shell’s sustainability and climate targets remain,” a company spokesman said.

Still, Mr Sawan has softened some of his predecessor’s environmental priorities.

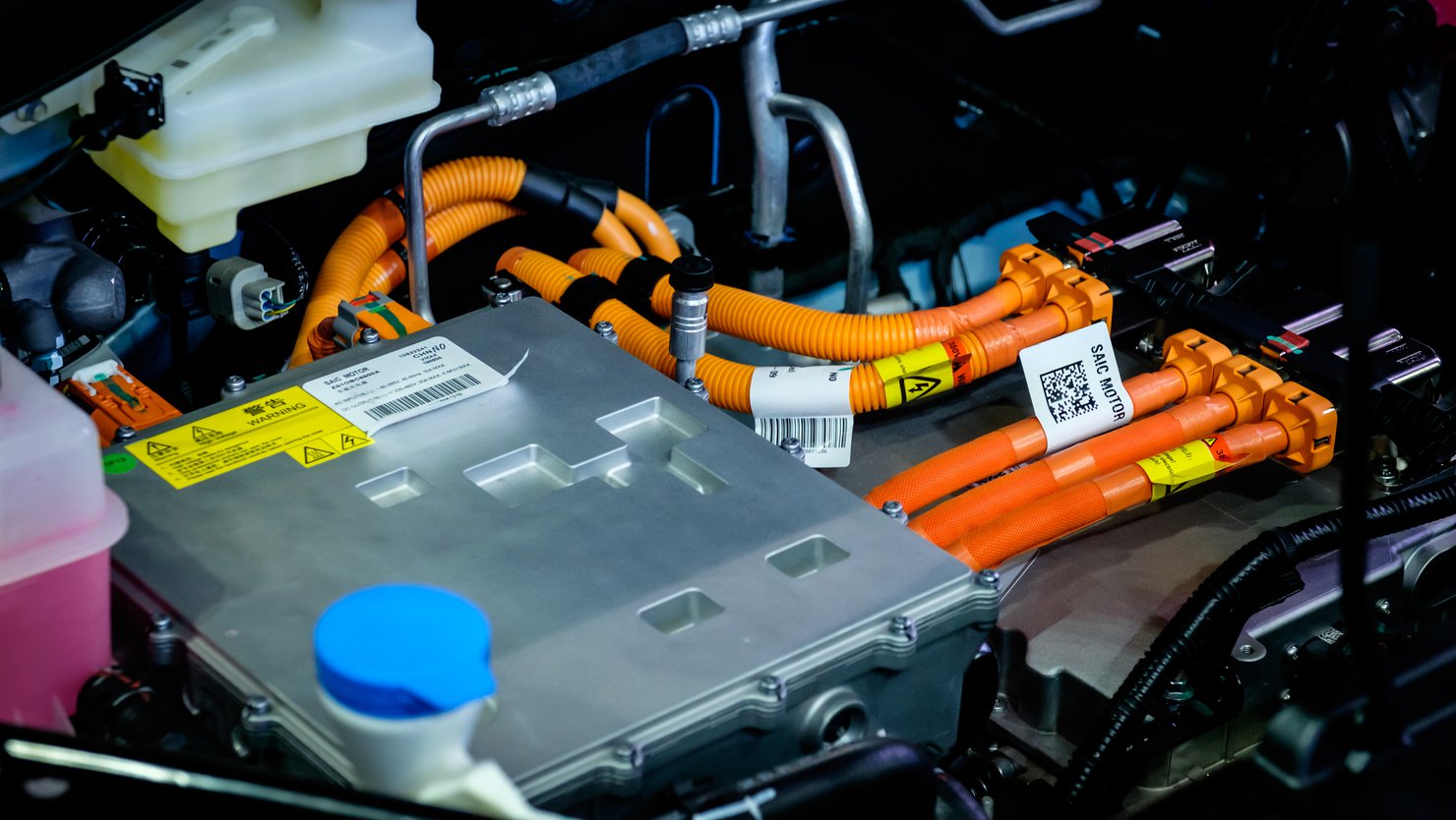

Along with ending the carbon offsets target, he eliminated a goal to increase power sales and vowed to be more selective with investments in renewable power, the backbone of the transition away from oil and gas. Shell also silently ditched a target to reach 500,000 electric vehicle charge points by 2025 and to have at least 10 per cent share of global clean hydrogen sales.

“The company has flipped to the short-term focus, to profit maximisation,” said Mr Adam Matthews, chief responsible investment officer at the Church of England Pensions Board. “They are no longer aligned with trying to navigate the transition in the same way that we had previously perceived.”

In spite of what Mr Matthews and others see as a significant shift, Shell has yet to adjust its long-term climate target of net-zero emissions by 2050.

And Shell has not abandoned its offsets efforts, yet its backup plan is revealing. Ms Ji said the company can also use offsets it acquires on the market to bolster its supplies. And, of course, that exposes Shell to the lower quality credits it was trying to avoid in the first place.

BLOOMBERG

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/MIGLHM2HZH6YB2RI6RLGUDUOFI.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/XCM74ZPYIFEU3LYTOKSCNZJKVA.jpeg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/L3GGIGJFWRG43LAOSIJWSWCQEQ.jpeg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/BFRV5PKXONEUNHZILPMSRJSTH4.jpeg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/7A3VKZCTYBHS3MJR3MMCQGMVEY.jpeg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/HF4A6W36SFDXNMHCD76GTT2D3I.jpeg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/WHWO5J4WNBFG3P5RKKBK6UHDDQ.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/WDO335YILRE3LJXYB4KGY5BRKI.jpeg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/S4HWCKZFBFCCXE4KIQB5VRQESA.jpeg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/BMYBSNYWCBDEPG7NGJ4MCDFBDI.jpeg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/MJTUOCT3N5CQDKOXSBXNSORNSA.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/P3MP657YUJBOTOM3UZGBUJZMEY.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/WSOQVUFEVZFKFAJXOBZZTDDR5M.JPG)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/3NHTMDKJQNGY7MIZDVDTLGPYE4.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/UYSYONRIJJFF3FV32D2A34XGYQ.JPG)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/F5XBPK3E3FD5PMWRQCF2HY4NNU.JPG)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/AUK4MXC24ZARXJHOZCGWTDP2E4.png)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/C5UFRYXTEJCOXBTVIY4CL4JQPY.png)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/OCHL2XAC4VDYHO7GWT362YOMDE.png)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/6UNJV7KWPVBJDP74S6YYC6HJSA.png)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/SXEYP6M3DBG4VPF3TYB4Y272P4.png)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/J4URPLWWFJHKTL3ASZOS4LRV64.png)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/GAIURNBKS5GZHPIZZ35QJKHNJI.png)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/FEBW34OCRRHTTG3CWEADV7B5LY.JPG)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/MBYFGZNV2RFDRKI4RP2CQWS7ZA.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/X6SGZCSBERHEVEHTWN5ZM66KIY.JPG)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/75FBT5I3GZGAHBWEJ4FFYAPCDA.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/S4ILHAJMIJFZZMNMW6LVWGUHDI.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/NNR2WPH2M5GTDNEJU263QCLMAE.png)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/VH4NZSRV4FGN3EDVW3LW4B7SIE.png)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/PHKRZEKUPRAHZOK2H6GAJCD3OQ.jpg)