From interfaith vegans to inclusive heathens, religious Parliament offers it all

The exhibit hall at the Parliament of the World’s Religions brought the diversity of religious practices and spiritual beliefs to life.

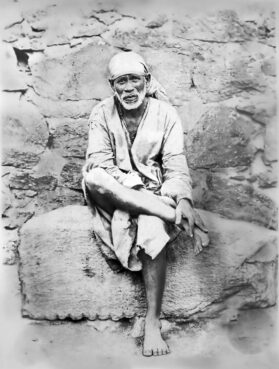

CHICAGO (RNS) — Not far from the entrance to an exhibitors space at Chicago’s McCormick Place stood a portrait of Swami Vivekananda, a Hindu monk and spiritual leader whose famed 1893 speech helped introduce Hinduism to the United States public and promoted the idea that people from different faiths can get along.

“I am proud to belong to a religion which has taught the world both tolerance and universal acceptance,” he said at the 1893 Parliament of the World’s Religions, credited with launching the modern interfaith movement. “We believe not only in universal toleration, but we accept all religions as true.”

The 2023 Parliament, which has drawn more than 6,000 faith leaders from around the world to Chicago, lives out Vivekananda’s vision in ways both big and small. In plenary sessions in a cavernous hall and in breakout sessions, religious leaders and activists challenged each other to address issues like climate change and the rise of authoritarianism.

In the exhibit hall, attendees chatted with each other, enjoyed massages and meditation, and learned about other religious faiths.

Swami Vivekananda’s portrait, for example, stood outside the booth for the Vivekananda Vedanta Society of Chicago, which was flanked by booths from the Theosophical Society and from the Chicago-based Brilliantly Mad collective, which promotes “art, music, spirituality, and well-being.”

Nearby was The Troth, which promotes inclusive heathenry, along with booths from Catholic and Buddhist religious orders.

A visitor to the Parliament of the World’s Religions exhibit hall picks up printed materials related to The Urantia Book on Aug. 15, 2023. Photo by Lauren Pond for RNS

Down the hall, near a booth from the Archdiocese of Chicago, a group of older folks who study The Urantia Book, a spiritual text first published in the 1950s, ran a booth with paperback and hardcover copies of the book, both in English and in Spanish. The book retells the history of the human race as well as the life of Jesus, as recounted by spiritual beings who are believed to have dictated the book to a pair of doctors, one who was also a minister, in Chicago.

Nathen Jansen, who runs an operational management company in Vancouver, and Rob Mastroianni, a family practice doctor from Maui, said they both began studying the book in the 1970s and have been hooked since.

“It couldn’t be anything but the truth because it’s so revealing,” said Jansen, who helps lead Zoom and in-person study groups.

Mastroianni said he was torn about coming to the Parliament in the wake of the wildfires in Maui. He had long planned to attend the Parliament and was also scheduled to teach at a training program for study group leaders in Chicago after the event.

He said that he’s been inspired by the way Hawaiians have rallied together after the fires.

“It’s a wonderful experience to see so many people so willing to help each other in any way possible,” he said.

Many of the booths offered materials explaining the basics of their beliefs and practice and selling resources or art related to their faith. A host of interfaith groups also had booths, such as Interfaith Alliance, Interfaith Light and Power, Interfaith Rainforest Initiative and the Interfaith March for Peace and Justice.

At the Interfaith Vegan Coalition booth, co-founder Lisa Levinson, who is Jewish, and volunteer Katie Nolan, who studies religion, handed out stickers with cartoon images of cows and elephants, with the message “Jesus Loves Me, Too” on them.

The group is a coalition of about 40 groups from different faiths, said Levinson, which advocates for the defense of animals and choosing a vegan life. They’ve protested Pope Francis’ visit to a circus where elephants were performing and sought to help faith groups find vegan alternatives for rituals that use animal products.

They said they hope to apply the golden rule — common to many faiths — to all beings, not just humans.

“We are certainly not protesting religion,” said Levinson. “What we want to do is support compassionate alternatives.”

Jonor Lama, right, demonstrates the vibrations of singing bowls for Diane Maltester, left, in the exhibit hall of the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago on Aug. 15, 2023. Maltester, a classical clarinetist, said she was interested in incorporating singing bowls into her music. Photo by Lauren Pond for RNS

Both Levinson and Nolan were also leading workshops during the Parliament, including one Nolan was leading on ethical fundraisers for religious nonprofits. Nolan said many faith communities often use events like barbecues or lobster boils — popular at Episcopal churches — to raise money for their work. She hopes to convince others to try alternative fundraisers that don’t involve animals or animal products.

“We’re trying to promote compassion and kindness, not just for humans but for all beings across all religions,” she said.

Next door was a booth from the Tzu Chi Foundation, a Taiwanese Buddhist group known for its disaster relief and ecological work. The foundation’s exhibit featured disaster relief supplies, such as a shelter and blankets made from recycled materials, as well as a chart promoting the climate benefits of eating a vegetarian diet, which has a lower carbon footprint.

Tzu Chi also had a booth explaining Buddhist beliefs, as well as a third booth for kids and families, with games and toys promoting recycling and taking care of the Earth.

Pick-Wei Lau, a volunteer at the Tzu Chi kids booth, said the foundation’s goal is to apply the teachings of the Buddha, especially about compassion, to everyday life.

Lau, who was manning the booth along with his kids, said he’d been struck that many of the people at the Parliament had similar hopes for their religious traditions — using their spiritual values for the common good.

“It’s eye-opening to see so many faiths under the same roof,” he said. “And yet — despite living different faiths, we are all speaking the same language, to be honest.”

Visitors to the exhibit hall could also take a break from the hectic pace of the Parliament. At a booth not far from a statue of Jesus set up by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, volunteers from Labourers for Christ Apostolic Ecumenical Network, a Chicagoland interfaith group, offered massages.

Nearby volunteers Archana and Atul Sakhare helped visitors try out a free meditation app in comfy chairs using headphones attached to a series of tablets at an exhibit from Heartfulness Institute, which teaches spiritual practices such as yoga and meditation.

Atul Sakhare, who works for Abbot in the Chicago suburbs, said he first began practicing meditation about 15 years ago.

“The first time I tried it, I thought I couldn’t stay for one minute,” he said. Instead, Sakhare said he stuck with it for 45 minutes. Now an enthusiastic advocate for meditation, he eventually became a volunteer trainer with the institute, which has centers around the world, including several in Chicago.

The group’s meditation app offers short, guided sessions — beginning as short as three minutes — with soothing music and a guide’s voice encouraging users to shut their eyes and relax their posture. Visitors to the booth could also download the app right at the booth.

Visitors to a booth run by the Federation of Zoroastrian Associations of North America could pick up brochures or buy books, including an illustrated board book of prayers for small children.

A Zoroastrian flag in the exhibit hall of the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago on Aug. 15, 2023. Photo by Lauren Pond for RNS

Ervad Kobad Zarolia, a Zoroastrian priest from Canada, said the federation represented several dozen centers. He said there are about 8,000 Zoroastrians in Toronto, where he lives, and said the community is thriving.

“We don’t give problems to anyone,” said Zarolia, a former engineer and retired insurance broker who immigrated to Canada from Bombay in his 20s. “Nobody gives us problems. That’s the way I look at it.”

He described the principles of Zoroastrianism — one of the world’s oldest religions — in three simple terms.

“We have three words we teach our children,” he said. “Good thoughts, good words, good deeds. You follow that, you are a saint.”