The ‘India problem’ under the surface at the Parliament of the World’s Religions

Hindu organizations say they were uniquely singled out for their views on the contentious Indian political atmosphere, leaving some Hindus wondering why they must be tied to the politics of India at an event centered on cultivating harmony between the world's religious communities.

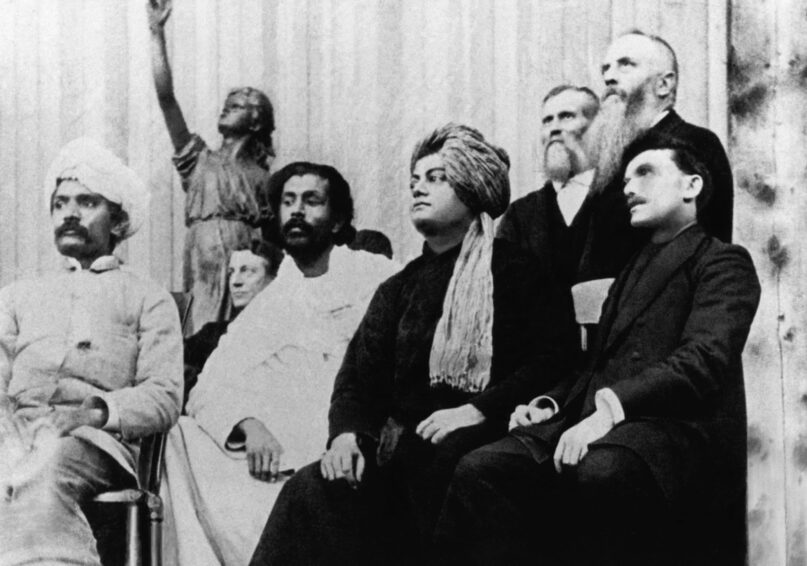

(RNS) — It has been over a century since Swami Vivekananda introduced the tenets of Hinduism to a Western audience for the very first time.

Vivekananda’s speech at the first Parliament of the World’s Religions — part of the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago — was a message of tolerance, mutual respect and universal acceptance.

The parliament, often referred to as the birth of the modern interfaith movement, held its ninth-ever conference this week at the McCormick Place convention center, with Hindus of all stripes present among diverse faith groups from across the world.

But some say Vivekananda’s legacy of inclusiveness is far from what they enjoyed at the parliament. Instead, Hindu organizations say they were uniquely singled out for their views on the contentious Indian political atmosphere, leaving some Hindus wondering why they must be tied to the politics of India at an event centered on cultivating harmony between the world’s religious communities.

From the monks of the Ramakrishna Mission and the educational efforts of Vivekananda Vedanta Society to the familiar “Hare Krishna” chanting of ISKCON, the Hindu presence at this year’s Parliament was philosophically and spiritually diverse.

Daily kirtans — musical devotional chants — and yoga nidra allowed those unfamiliar with the tradition to experience the many forms of worship and intellectual exercises that form the Sanatana Dharma tradition.

Devotees of Amma Sri Karunamayi, a Hindu spiritual leader, use their smartphones to record her speech during a Climate Repentence Ceremony at the parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago on August 15, 2023. Photo by Lauren Pond for RNS

Hindus were also involved in discussions on combatting climate change and the misuse of the swastika, an ancient Hindu symbol that was appropriated by Nazis into their Hakenkreuz, or “hooked cross,” symbol.

Nivedita Bhide, part of the Indian organization Vivekananda Kendra, was set to be a featured luminary in the parliament’s plenary. But days before the conference, Bhide’s speaking engagement was dropped due to activists sounding the alarm on her allegedly Islamophobic statements on social media and ties to Hindu nationalist ideology.

Parliament leaders did not address specific concerns from Hindu groups about Bhide’s cancelation.

“The parliament is presently concluding its convening in Chicago with more than 7,000 attendees with very broad and deep Hindu participation that we are grateful for,” the Parliament of the World’s Religions said in a statement to Religion News Service. “The parliament is open to people of all religions, spiritual paths and ethical convictions, consistent with the values of respectful dialogue. We seek to promote harmony and partnerships amongst world’s religions and spiritual communities on issues that humanity faces today.”

The far-right nationalist ideology that Bhide was accused of following has been embraced by supporters of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Hindu-majority India has been on the USCIRF’s watchlist for countries eroding religious freedom because of increasing concerns about the oppression and marginalization of Muslim and Christian minorities.

Given that the 2023 Parliament’s theme was “A Call to Conscience: Defending Freedom and Human Rights,” Bhide’s alleged embrace of Hindu Nationalism was out of place for a conference speaker. But some American Hindus feel they were the only diaspora group in attendance that was singled out to answer for their ancestral homeland’s woes.

Richa Gautam. Photo via Twitter

Richa Gautam, the founder of Castefiles.com, said that one of the highlights of the conference was engaging in dialogue with groups that are not often on Hindu Americans’ radar — people of the Bahai faith, indigenous traditions and pagans.

But Gautam argued that Bhide’s cancelation was part of a series of attempts to “target and cancel Hindu voices, even those that speak for spiritualism.”

“If you’re coming for a ‘kumbaya’ conference, you might as well allow everyone,” said Gautam. “That is the magnanimity and generosity you would expect by people who are driven by spiritual or religious conversation and dialogue. But obviously, that wasn’t the case.”

Multiple discussions of Hindu nationalism were held by groups like Hindus for Human Rights and the Indian American Muslim Council. The Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh and World Hindu Council (also referred to as VHPA) were also in attendance, along with the Hindu American Foundation and the Coalition of Hindus of North America.

Vocal critics of the Hindu right, including South Asian history scholar Audrey Truschke, spoke at the parliament on Friday about the threats and harassment she has received from right-wing groups due to her scholarship on Hindu nationalism.

“I’m happy to see the Parliament of World Religions (@InterfaithWorld) take far-right religious nationalism seriously and remove some Hindu nationalists,” she wrote on X, the site formerly known as Twitter, after Bhide was dropped as a speaker. “It’s not perfect; they missed some. But it’s a step towards condemning bigotry and enabling a greater diversity of voices.”

The Indian American Muslim Council has long been fighting to expand awareness of the unequal treatment of Muslims in India under the BJP’s rule. A banner from the Indian American Muslim Council named the Hindu American Foundation and a series of other American Hindu groups as “Hindutva Organizations in America.”

Mat McDermott. Photo by Tejus Shah/HAF

The term “Hindutva” translates to “Hindu-ness,” but refers to Hindu nationalism.

Mat McDermott, the communications director for Hindu American Foundation, says the claims made on IAMC’s banner, including that the group “lobbies for Indian politicians and supports a beef and Hijab ban,” were categorically untrue. McDermott was personally called out on X and in person at a Hindu nationalism panel for working with a “right-wing hate group.” To some, he says, HAF is no different than Hindu extremists calling to expel Muslims.

“I was livid,” said McDermott. “We were not talking about anything to do with India, nor anything HAF and IAMC had clashed on in the past.”

McDermott said the nonprofit organization, which has been around since 2003, has long been the target of academics and activists. McDermott said the HAF’s views are “pretty much in the center” and argued that it is increasingly difficult to have nuanced views on the Indian government in left-wing spaces.

“In the current public discourse, it’s “you’re with us or you’re against us,” said McDermott. “You’re irredeemable if you don’t condemn the government of India outright.”

This is not the first time politics has gotten in the way of Hindus and the parliament. In 2013, the parliament canceled its co-sponsorship of Swami Vivekananda’s 150th birthday celebration in Chicago, where Indian yogi and ayurveda businessman Baba Ramdev gave a speech, without revealing why.

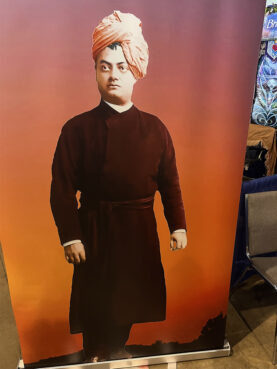

A poster of Swami Vivekananda during the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago on Aug. 15, 2023. RNS photo by Bob Smietana

As a result, the only Hindu members of the parliament’s board of directors resigned.

“To completely ignore issues of fairness, transparency, and mutual respect raised by the Hindu community at large and the condescending tone of the announcement should call into question the parliament’s ability to be a global leader in the interfaith movement,” said Pawan Deshpande, a member of HAF’s executive council, back in 2013.

Nikunj Trivedi, the president of the Coalition of Hindus of North America, said Hindus are accepted when they are peaceful and apolitical, but not when they raise their voices about issues like Hinduphobia.

“A good Hindu should never talk about the problems Hindus face,” said Trivedi. “The minute they do, they are called a Hindu nationalist. They are canceled.”

He says many Americans are already misinformed about the Hindu religion and that critics of the Modi regime are contributing to a negative image of the Hindu diaspora. Instead of building spiritual, religious and philosophical bridges of understanding, he says, some are contributing to the perspective that Hindus should not be involved in these types of conferences.

“It creates this idea that Hindus are not good people, who endorse violence, ethnic cleansing and genocide,” said Trivedi. “The treasures of our culture are completely sidelined by creating this monstrous idea that this entire community is out to get someone.”

For some Hindus, Vivekananda’s legacy becomes tarnished when the parliament becomes politicized.

“I fervently hope that the bell that tolled this morning in honor of this convention may be the death-knell of all fanaticism, of all persecutions with the sword or with the pen, and of all uncharitable feelings between persons wending their way to the same goal,” Vivekananda said in his famed 1893 speech.

Rakhi Israni is the legal director for HinduPACT, a policy initiative of the VHPA. She is also on the board of advisers for the Vivekananda Yoga University. Israni says it is okay if discussions of politics help someone understand religion or faith a little better, but not if they are used to shut down others’ viewpoints.

“A forum like this should really be about faith, spirituality and the uplifting of people in general,” said Israni. “Vivekananda’s speech opened a lot of people’s minds to the idea that we are all one family, or in the Hindu philosophy, ‘Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam.'”

Opinion

Explaining the Hindu divide at the Parliament of the World’s Religions

It shouldn’t be hard to see why fusing of religious and national identity causes anxiety and fear.

(RNS) — At the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago last week with the theme of defending human rights, several Hindu groups complained that, at an event that celebrates common ground among religious communities, they were tied unfairly to India’s contentious religious politics.

What those who complained didn’t address was that they, along with a growing number of Hindu organizations in India and in the United States, have tied themselves to those contentious and aggressive politics. These groups ought not to be surprised when their views on the relationship between religion and the nation-state is called out in public spaces, especially because these ideologies contribute to tension and violence in India and elsewhere.

In fact, the Parliament of the World’s Religions, where religions come together to discuss global challenges and solutions, is precisely the place to raise such concerns. The purpose of the gathering is not to promote a superficial harmony or to overlook issues that divide religions. It is naïve to suggest, as one attendee did, that the parliament is a “kumbaya” event and should uncritically give a platform to even dangerous ideologies.

But the complaints aired after the parliament go beyond politics. They reflect a deepening divide between (at least) two ways of thinking about Hindu identity and the meaning of Hinduism as a religious tradition. These different ways of thinking about Hinduism are also present in relationships with other traditions.

On one side of the divide are those Hindu organizations influenced, in varying ways, by the ideology systematized and expounded by the mid-20th-century figure V.D. Savarkar known as Hindutva (Hinduness), in a well-known book by the same name. Savarkar tied religious identity to national identity by defining a Hindu as a citizen of India, as a descendant of Hindu ancestors, as a participant in a shared Sanskrit culture and as one who regards India as a holy land.

On the basis of these criteria — and especially the last two — Savarkar included Jains, Sikhs and Indian Buddhists in his category of “Hindu,” but excluded Indian Muslims and Indian Christians. In Savarkar’s view, Muslims and Christians “ceased to own Hindu civilization (Sanskriti) as a whole. They belong or feel that they belong to a cultural unit altogether different from the Hindu one.”

In essence he accused nondharmic Indians of having a divided love and loyalty, of regarding lands outside of India as sacred, of venerating leaders and professing beliefs that did not originate in India and of venerating their holy lands above India. In his view, they do not belong to India in the same way as Hindus.

It shouldn’t be difficult to understand why a clear fusing of religious and national identity that privileges Hindus causes anxiety and fear in those who are excluded. Hindutva is associated with hostility, mistrust and increasing violence toward communities that do not satisfy his criteria.

Savarkar’s equation of Hinduism and India, which overlooked the universal claims of Hinduism, reduced it to the religion of a particular ethnic and national group. A religious nationalism that divinizes the nation and its defense and service only diminishes both faith and nation. It is not surprising that some adherents to this ideology see criticism of India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi with the negativization of Hinduism.

Savarkar’s version of Hinduism is not irrelevant. It is alive in various contemporary organizations, such as the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and its affiliates, many of which have partner associations in the United States, some of which participated in the Parliament of the World’s Religions. It is significant that on Feb. 26, 2003, amid controversy, a portrait of Savarkar was unveiled in the Central Hall of the Indian Parliament, facing a portrait of Mahatma Gandhi.

On the other side of the Hindu divide are those groups, also present in Chicago last week, that do not conflate religious and national identities, for whom “Hindu” connotes a universally accessible religious identity transcending nationality, ethnicity and South Asian culture.

For these groups, being Hindu is not the same as being Indian. Nourished by spiritual traditions originating in India, these groups honor the sacred geography of India, but veneration for India is not a requirement of Hindu identity and a criterion of exclusion. Love for India is not anti-Muslim or anti-Christian.

These groups lift up the ancient and powerful tradition of hospitality to religious diversity in the Hindu tradition. The tradition has made it possible for Indian Hindus to accommodate the country’s wide diversity of religious beliefs and practices and to offer shelter to persecuted religious groups for centuries. They see the Hindu tradition as offering a theological understanding of religious diversity that complements diversity in the civic sphere and counters the use of state power on behalf of a particular religion. They advocate for diversity, justice, dignity, and the equal worth of all human beings.

Hinduism has never been a homogeneous tradition, but today what is most likely to distinguish one Hindu from another is their understanding of the relationship between Hinduism and the state. Organizations that describe themselves as Hindu in the U.S. are obliged to be explicit about their view of the topic, and failure to do so leaves room for misunderstanding.

Historically, the interests of the state and the deeper purposes of religious teachings rarely coincide. In the long run, the refusal to critically distinguish the universal and humanistic teachings of the Hindu tradition from the specific, historical expression of the Indian state will do a grave disservice to the religion. It will limit the potential of the tradition to be a blessing for the world.

(Anantanand Rambachan is emeritus professor of religion at St. Olaf College. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)