In this op-ed, writer Casey Haughin-Scasny explores the virality of the recent “How often do you think about the Roman Empire?” TikTok trend in the context of how history is constructed.

I am a woman who thinks about the Roman Empire every single day. Not just the innovations of its legal system, or its monumental architecture, or even the staggering scale of its bureaucracy, but about the way its historical legacy has been written and rewritten, and how we understand the realities of life in its past.

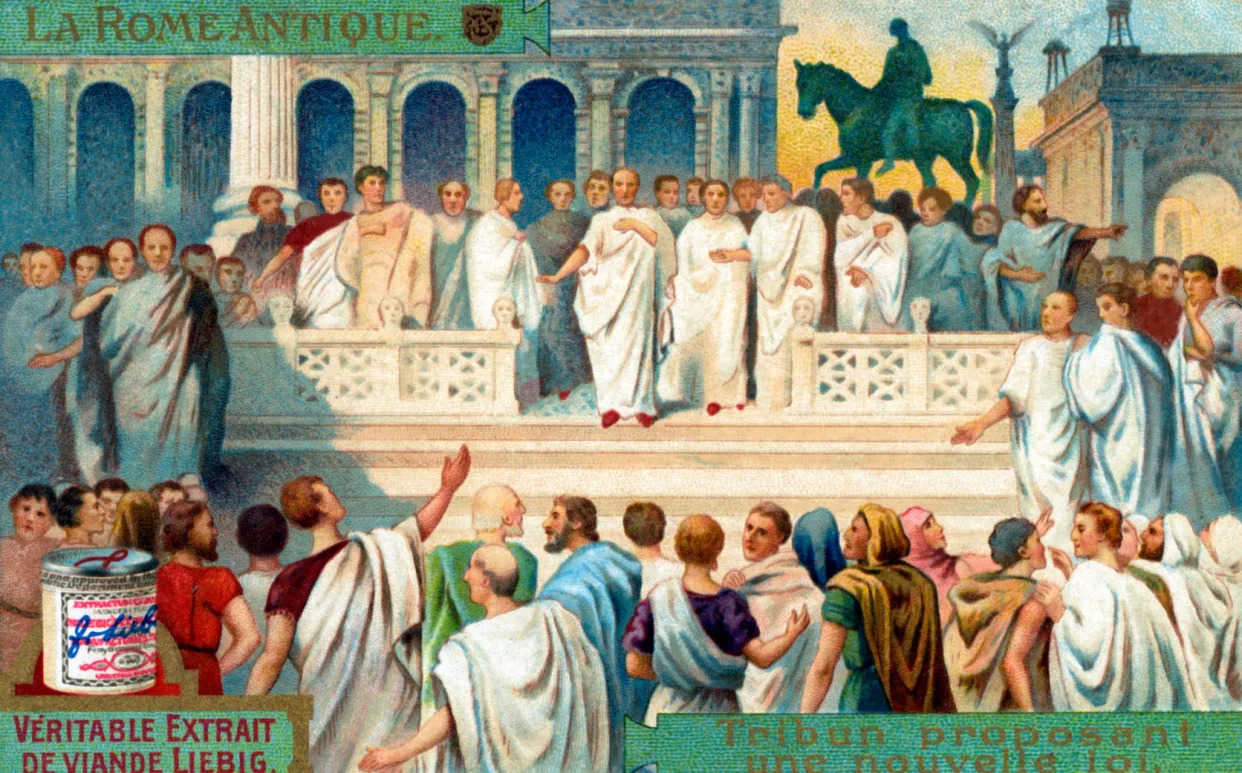

The recent TikTok trend hinges on a simple question, with women asking their male partners, family members, or friends about the frequency of their ruminations on Rome. The recorded responses range from confusion over the very term “Roman Empire” to opinions about the legitimacy of different emperors. While there is a fair share of men who don’t think about the Roman Empire at all, the absurdist comedy of the question hinges on the prevalence of men who do think about the Roman Empire, almost reverently or obsessively, unbeknownst to their female loved ones.

The revelations, shared on TikTok, have generated a deluge of content that involves (predominately white) men justifying their interest, often appealing to the “lessons” to be learned from the Empire’s rise and fall, or the importance of Rome in the modern world. Women, in response, have asked each other what the female “Roman Empire” is—that is, to say, what women regularly think about in history that men are not aware of. Responses have varied, but they primarily include the Titanic, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, the Romanovs, and Greek mythology.

It could be another harmless internet fad, except for what it implies about the way history is passed down and constructed. The trend demonstrates how popular perceptions of Rome rely on an interpretation of history that many scholars now recognize to be actively harmful, both to our ability to understand the ancient past and to our society at large.

My work as a PhD candidate in public history examines how Americans have used, abused, and misconstrued the ancient past in order to make meaning in their present from the 18th century to today. I am also an archaeologist who has participated in the excavation of a Roman villa since I was 19. I teach classes on Roman art and archeology. Since my first introduction to Latin at the age of eleven I have been fascinated with Rome. I would say between now and then there is likely not a day that has gone by that I have not thought about the Roman Empire. My gender does not prevent me from joining in on the fun. Women are interested in the ancient past! Who knew?

Many folks don’t. And there’s a reason for that.

The commentaries on TikTok reveal the prevalence of the “great man” narratives that progressive scholars have worked so hard in recent years to supplement, challenge, and contextualize. The Roman Empire that exists within the minds of TikTok users is one that is inherently of interest to men — and, given the way it’s being talked about, why wouldn’t it be? It’s something of a Kendom, really. Maybe the Domus Aurea is the original Mojo Dojo Casa House.

Much of the image that we have constructed around Rome in popular culture — its place as the basis of “Western” civilization, the brilliance of its expansion under various male emperors and generals, the superiority of its rulership, the inevitability of its demise — relies on outdated imaginations of the ancient world. A significant part of this narrative involves androcentric interpretations of the past that emphasize “great man” history over the lives of the vast majority of the Empire’s citizens.

In the fascination over emperors and their proclivities for conquest, we lose sight of the complex tapestry that influenced daily life in the Roman empire. Not only that, we often risk reaffirming the very active schools of thought within white supremacist circles that these Roman “white” men were naturally positioned to conquer the known world due to their innate superiority. This might sound dramatic, but it’s not — there’s an entire country as proof. All we have to do is look to the very foundation of America, from its governance to its laws to its architecture and so many things in between, to see how ideas about ancient Rome’s success and values have been purposefully taken on, manipulated, and baked into power structures that continue to marginalize communities to this day (Dr. Lyra D. Monteiro’s phenomenal article “Power Structures: White Columns, White Marble, White Supremacy” is a great introduction to the issues at hand). Uncritical praise of Rome for all the seemingly positive things it’s given us does little to unpack how this heritage has been leveraged historically.

I’m not out here trying to say that Rome was some kind of egalitarian paradise where women were seen as equals in the eyes of the law or in social situations. In fact, I’m saying the opposite — Rome was an inherently unequal society, and the Pax Romana that so many admire was built on the oppression of various demographics, women among them. When we simply focus on great men in these histories and romanticize imperialism, we lose the opportunity to understand how marginalized groups navigated these circumstances in ways ranging from the mundane to the extraordinary. We also lose the opportunity to consider why people from historically marginalized backgrounds would want to learn about Rome now.

The trend’s relegation of women’s interests in antiquity to mythology, and specifically Greek mythology, further reveals the divides that are so prevalent in the popular and academic studies of ancient history. Rome stands as the powerful, militaristic foil to Greece’s more refined, softer lifestyle, and mythology as a more appropriate option for women’s interests than the intricacies of rule and bloodshed. This divide is, of course, artificial. That hasn’t stopped generations of people from relegating women to limited, “appropriate” areas of study, if they’re permitted to engage with antiquity at all, or assuming that women are incapable of or uninterested in engaging with traditionally “masculine” aspects of the ancient past like epics or tactical histories. This isn’t to say that women can’t be interested in mythology — it’s awesome! But there’s nearly a millennium of baggage to consider before we accept these divisions wholesale.

The men who are featured on TikTok are almost certainly not considering the legacies above when they’re thinking about the Roman Empire. And that’s exactly the issue — as long as these assumptions about the past are commonplace, the harm that is done by their invocation will persist. The trend reveals just how pervasive longstanding assumptions about Rome are, and when these assumptions remain unchecked, we’re able to see the consequences.

The presumption that women aren’t interested in these histories comes from these biases, but it’s not an innocent one. Even if we put aside all of the other issues I’ve outlined here, the impact these biases have on the study of antiquity is alive and well. I regularly watch male colleagues as their eyes glaze over while female colleagues talk about their work on social histories of the Roman Empire or the pitfalls of ancient reception, while men I meet in my life outside academia assume their cursory knowledge based on this imagined past is equivalent or superior to my knowledge after a decade of training. I’ve sat through too many disrespectful Q&As to not understand the consequences of the possessiveness men hold over Rome in how it affects women’s abilities to engage with ancient history. This article doesn’t even scratch the surface of how these issues are amplified for scholars who occupy intersecting identities as people of color, or members of the LGBTQIA+ community, or are disabled (like myself), topics that responses on TikTok have also grappled with as the trend gains popularity. The imagination of ancient Rome affects people in far more ways than gender.

And I’m sick of it.

I’m not accusing the men featured in TikTok videos of harboring these feelings about gender, race, or imperialism. However, to ignore the subtext of this trend would be to pass up an opportunity to discuss the presence of the ancient world in our modern lives, and all the baggage that comes with it. So, I have to ask: how often do you think about why we think about the Roman Empire?

Originally Appeared on Teen Vogue