An Osage delegation with President Calvin Coolidge at the White House on Jan. 20, 1924. Bettman via Getty Images

Director Martin Scorsese’s new movie, “Killers of the Flower Moon,” tells the true story of a string of murders on the Osage Nation’s land in Oklahoma in the 1920s. Based on David Grann’s meticulously researched 2017 book, the movie delves into racial and family dynamics that rocked Oklahoma to the core when oil was discovered on Osage lands.

White settlers targeted members of the Osage Nation to steal their land and the riches beneath it. But from a historical perspective, this crime is just the tip of the iceberg.

From the early 1800s through the 1930s, official U.S. policy displaced thousands of Native Americans from their ancestral homes through the policy known as Indian removal. And throughout the 20th century, the federal government collected billions of dollars from sales or leases of natural resources like timber, oil and gas on Indian lands, which it was supposed to disburse to the land’s owners. But it failed to account for these trust funds for decades, let alone pay Indians what they were due.

I am the manager of the University of Arizona’s Indigenous Governance Program and a law professor. My ancestry is Comanche, Kiowa and Cherokee on my father’s side and Taos Pueblo on my mother’s side. From my perspective, “Killers of the Flower Moon” is just one chapter in a much larger story: The U.S. was built on stolen lands and wealth.

Members of the Osage Nation attend the premiere of ‘Killers of the Flower Moon’ on Sept. 27, 2023, in New York City.

Dia Dipasupil/Getty Images

In the standard telling, the American West was populated by industrious settlers who eked out livings from the ground, formed cities and, in time, created states. In fact, hundreds of Native nations already lived on those lands, each with their own unique forms of government, culture and language.

In the early 1800s, eastern cities were growing and dense urban centers were becoming unwieldy. Indian lands in the west were an alluring target – but westward expansion ran up against what would become known was “the Indian problem.” This widely used phrase reflected a belief that the U.S. had a God-given mandate to settle North America, and Indians stood in the way.

In the early 1800s, treaty-making between the U.S. and Indian nations shifted from a cooperative process into a tool for forcibly removing tribes from their lands.

Starting in the 1830s, Congress pressured Indian tribes in the east to sign treaties that required the tribes to move to reservations in the west. This took place over the objections of public figures such as Tennessee frontiersman and congressman Davy Crockett, humanitarian organizations and, of course, the tribes themselves.

Forced removal touched every tribe east of the Mississippi River and several tribes to the west of it. In total, about 100,000 American Indians were removed from their eastern homelands to western reservations.

But the most pernicious land grab was yet to come.

Eastern Native American tribes that were forced to move west starting in the 1830s.

Smithsonian, CC BY-ND

The General Allotment Act

Even after Indians were corralled on reservations, settlers pushed for more access to western lands. In 1871, Congress formally ended the policy of treaty-making with Indians. Then, in 1887, it passed the General Allotment Act, also known as the Dawes Act. With this law, U.S. policy toward Indians shifted from separation to assimilation – forcibly integrating Indians into the national population.

This required transitioning tribal structures of communal land ownership under a reservation system to a private property model that broke up reservations altogether. The General Allotment Act was designed to divvy up reservation lands into allotments for individual Indians and open any unallotted lands, which were deemed surplus, to non-Indian settlement. Lands could be allotted only to male heads of households.

Under the original statute, the U.S. government held Indian allotments, which measured roughly 160 acres per person, in trust for 25 years before each Indian allottee could receive clear title. During this period, Indian allottees were expected to embrace agriculture, convert to Christianity and assume U.S. citizenship.

In 1906, Congress amended the law to allow the secretary of the interior to issue land titles whenever an Indian allottee was deemed capable of managing his affairs. Once this happened, the allotment was subject to taxation and could immediately be sold.

A 2021 study estimated that Native people in the U.S. have lost almost 99% of the lands they occupied before 1800.

Legal cultural genocide

Indian allottees often had little concept of farming and even less ability to manage their newly acquired lands.

Even after being confined to western reservations, many tribes had maintained their traditional governance structures and tried to preserve their cultural and religious practices, including communal ownership of property. When the U.S. government imposed a foreign system of ownership and management on them, many Indian landowners simply sold their lands to non-Indian buyers, or found themselves subject to taxes that they were unable to pay.

In total, allotment removed 90 million acres of land from Indian control before the policy ended in the mid-1930s. This led to the destruction of Indian culture; loss of language as the federal government implemented its boarding school policy; and imposition of a myriad of regulations, as shown in “Killers of the Flower Moon,” that affected inheritance, ownership and title disputes when an allottee passed away.

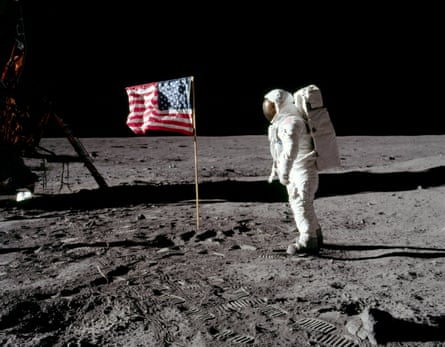

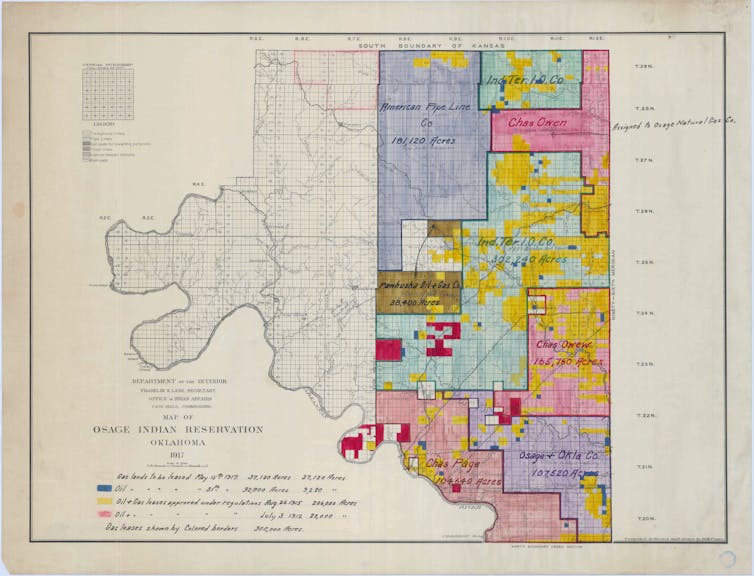

A 1917 map of oil leases on the Osage Reservation.

HUM Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Today, about 56 million acres remain under Indian control. The federal government owns title to the lands, but holds them in trust for Indian tribes and individuals.

These lands contain many valuable resources, including oil, gas, timber and minerals. But rather than acting as a steward of Indian interests in these resources, the U.S. government has repeatedly failed in its trust obligations.

As required under the General Allotment Act, money earned from oil and gas exploration, mining and other activities on allotted Indian lands was placed in individual accounts for the benefit of Indian allottees. But for over a century, rather than making payments to Indian landowners, the government routinely mismanaged those funds, failed to provide a court-ordered accounting of them and systematically destroyed disbursement records.

In 1996, Elouise Cobell, a member of the Blackfeet Nation in Montana, filed a class action lawsuit seeking to force the government to provide a historic accounting of these funds and fix its failed system for managing them. After 16 years of litigation, the suit was settled in 2009 for roughly US$3.4 billion.

The settlement provided $1.4 billion for direct payments of $1,000 to each member of the class, and $1.9 billion to consolidate complex ownership interests that had accrued as land was handed down through multiple generations, making it hard to track allottees and develop the land.

“We all know that the settlement is inadequate, but we must also find a way to heal the wounds and bring some measure of restitution,” said Jefferson Keel, president of the National Congress of American Indians, as the organization passed a resolution in 2010 endorsing the settlement.

Elouise Cobell shakes hands with Interior Secretary Ken Salazar at a Senate hearing on the $3.4 billion Cobell v. Salazar settlement. Cobell, a member of the Blackfeet Nation, led the suit against the federal government for mismanaging revenues derived from land held in trust for Indian tribes and individuals.

Mark Wilson/Getty Images

Who are the wolves?

“Killers of the Flower Moon” offers a snapshot of American Indian land theft, but the full history is much broader. In one scene from the movie, Ernest Burkhart – an uneducated white man, played by Leonardo DiCaprio, who married an Osage woman and participated in the Osage murders – reads haltingly from a child’s picture book.

“There are many, so many, hungry wolves,” he reads. “Can you find the wolves in this picture?” It’s clear from the movie that the town’s citizens are the wolves. But the biggest wolf of all is the federal government itself – and Uncle Sam is nowhere to be seen.

Torivio Fodder, Indigenous Governance Program Manager and Professor of Practice, University of Arizona

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.