National Bank of Canada has cut a number of jobs in its capital markets business, according to people with knowledge of the matter.

The move included reductions in the equity research and sales and trading divisions, the people said, speaking on condition they not be named because they aren’t authorized to discuss the matter publicly.

Marie-Pierre Jodoin, a spokesperson for the Montreal-based bank, said it has made “a few adjustments to our Financial Markets structure based on the ongoing assessment of business needs and priorities.” She didn’t provide a number.

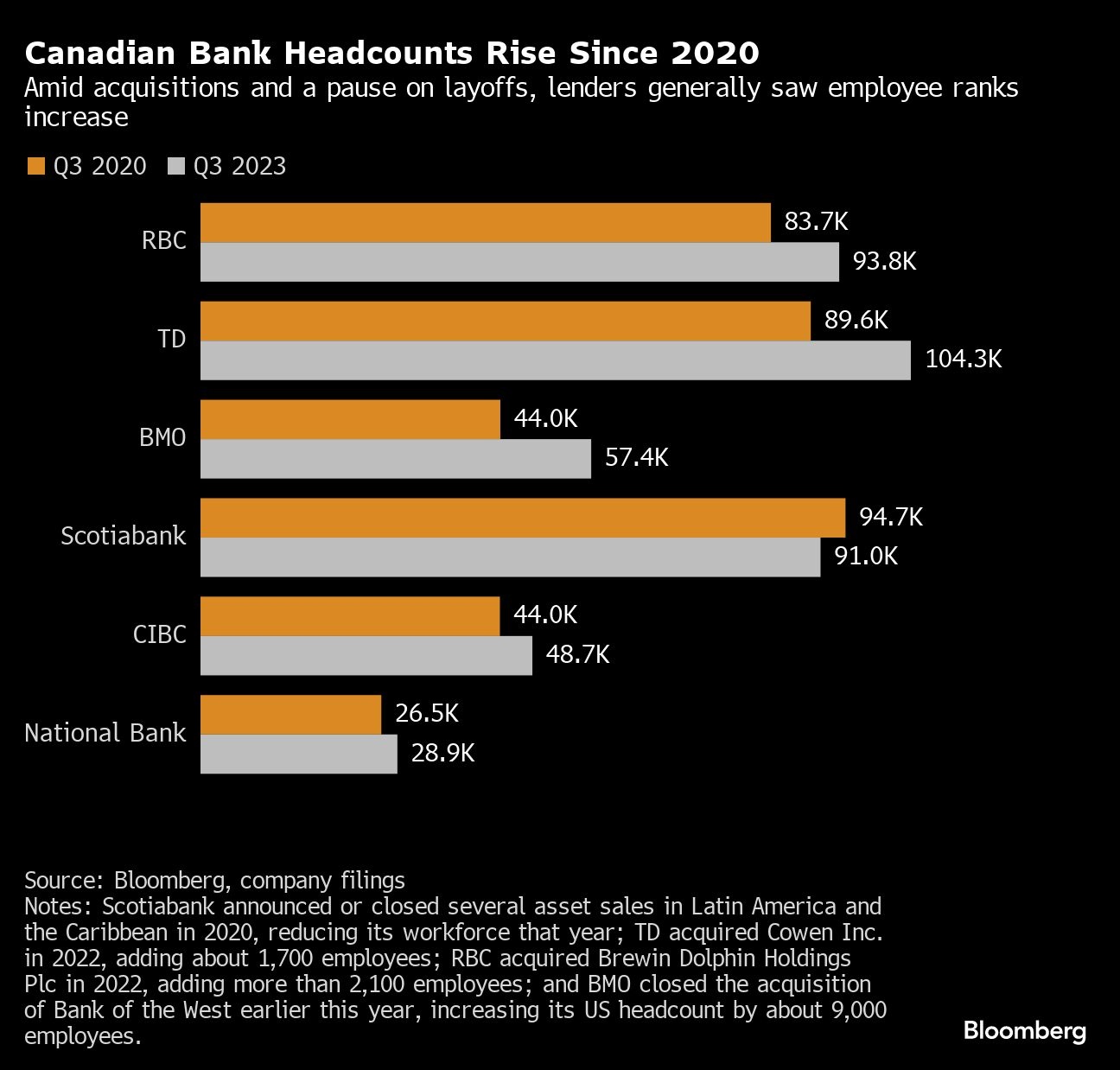

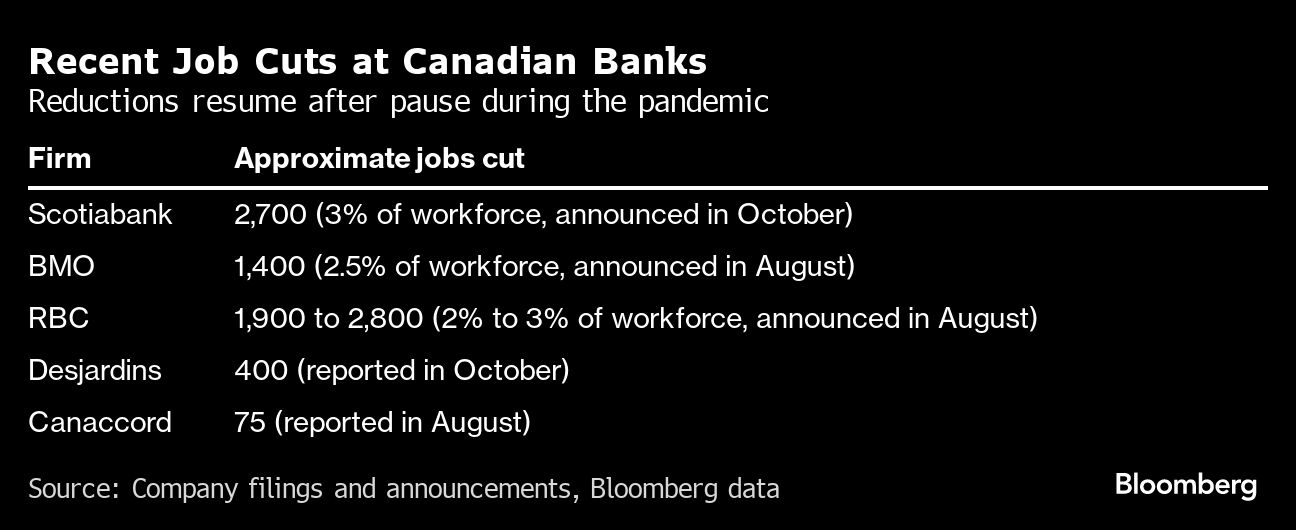

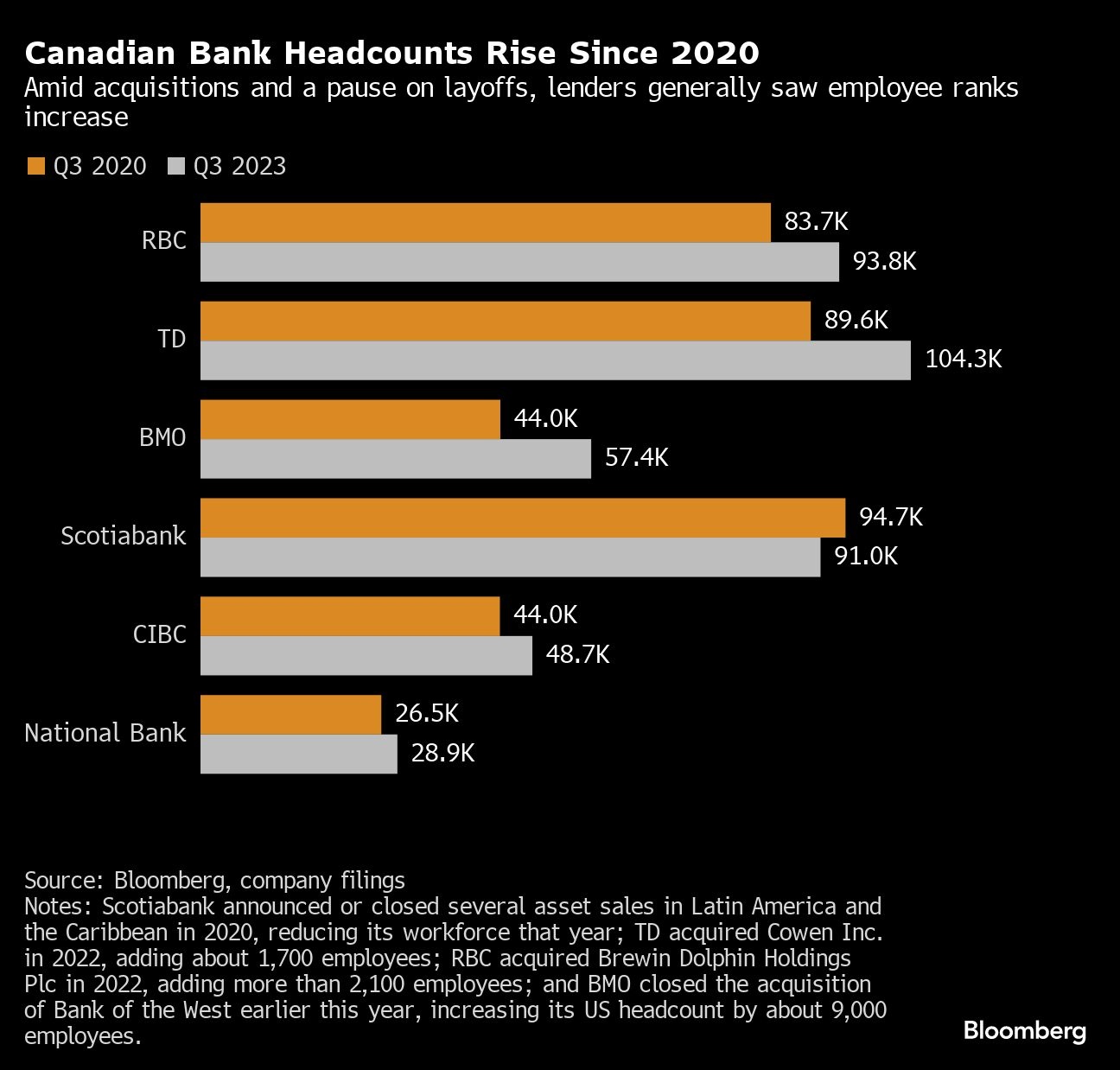

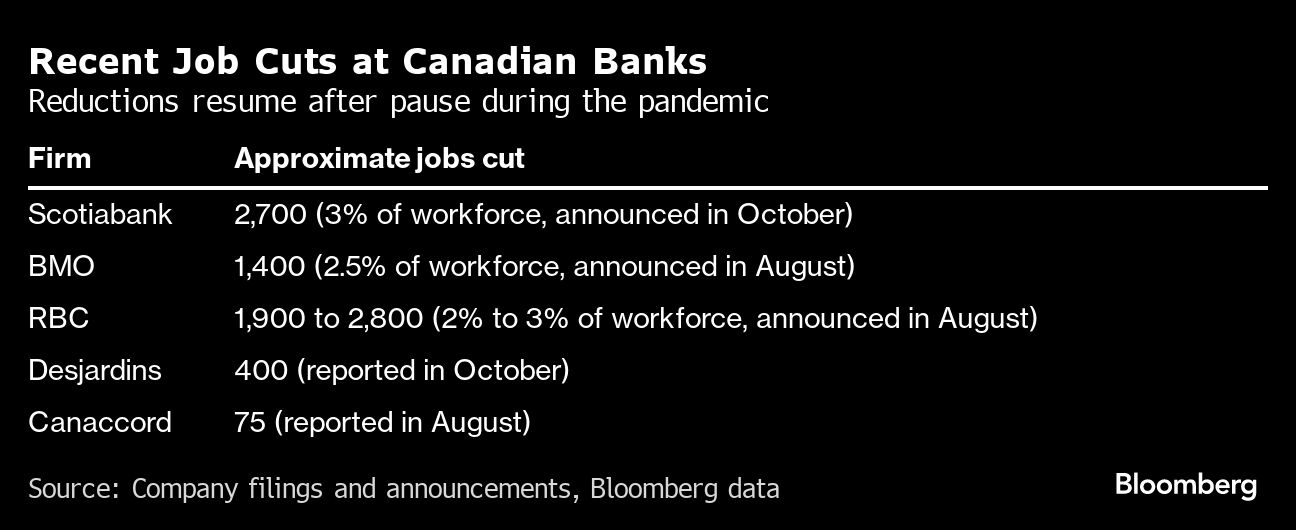

The layoffs at National Bank, Canada’s sixth-largest bank, come amid a wave of job cuts at other Canadian lenders over the past few months that have totaled at least 6,000. Bank of Montreal, Royal Bank of Canada and Bank of Nova Scotia have announced layoffs representing 2 per cent to 3 per cent of their workforces.

Canada’s large banks had largely avoided job cuts for the past three years, but in the face of numerous revenue and capital pressures, they’re now looking to trim expenses ahead of the Oct. 31 end of their fiscal years.

National Bank had 28,901 employees as of July 31. Executives said during its third-quarter earnings call in August that expenses had grown during the period, largely because of an increase in full-time positions in 2022.

Chief Financial Officer Marie Chantal Gingras told analysts at the time that the bank was focused on “prudently managing headcount through attrition.”

Employees recently laid off from the Canadian banking sector will have options when it comes to severance, and the best choice depends on each individual’s personal circumstances, according to an employment lawyer.

Last week, Desjardins announced it intends to lay off about 400 employees, while Scotiabank announced it would cut about 3 per cent of its staff.

LUMP SUM OR SALARY CONTINUATION

Ryan Kornblum, an employment and labour lawyer with Kornblum Law, said recently laid-off employees are often given two distinct options when it comes to severance: a lump sum or salary continuation. The best option for each worker depends on their future job prospects, Kornblum explained.

“The stronger you think your prospects are, the more you’re going to lean toward a lump-sum option, generally speaking,” he told BNN Bloomberg Monday in a television interview.

“The discount they’re going to want you to take is about 25 per cent, so generally if you have a salary continuous option, you’ll take 25 per cent less if it’s lumped out.”

Those who think they might be hired quickly are then able to enjoy the lump sum knowing they have a new job on the horizon, he said. Those who are a little more worried about employment prospects can take the continued salary, which gives them more time to look for a job and receive that extra 25 per cent, Kornblum added.

Despite layoffs in the bank sector, Kornblum said he believes many workers will be able to find a new job fairly quickly, noting that severance in the banking sector tends to be more generous than in other careers.

“Even though we are seeing bank layoffs this week and last week, it is a pretty hot jobs market and people are more inclined to take that lump and hope to get that job quicker,” he said.

Canadian banks have resumed cutting jobs after a three-year hiatus, with lenders and investment banks so far dismissing at least 6,000 workers, and analysts predicting more to come as revenue remains under pressure.

Bank of Nova Scotia, Royal Bank of Canada and Bank of Montreal all disclosed plans in the past few months to reduce headcount by 2 per cent to 3 per cent, while smaller players Desjardins Group and Canaccord Genuity Group Inc. have also trimmed staff.

“This is probably just the beginning stages,” said Mike Rizvanovic, an analyst at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods. “The rest will depend on how things recover and if you go into a recession. There’s always potential for more.”

The moves come as Canadian lenders grapple with numerous stresses. As with banks in other countries, they’ve seen a significant jump in the cost of deposits and a slowdown in new mortgages. And deals have stalled in their capital-markets businesses: There hasn’t been a completed initial public offering of more than $500 million (US$360 million) in Canada this year, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Meanwhile, as credit conditions deteriorate, with housing and commercial real estate under pressure, the banks are expected to take significant loan-loss provisions in the fiscal fourth quarter. And they may be facing another increase in the minimum amount of capital regulators require them to hold.

Wall Street banks resumed cutting staff months earlier, and, in some cases, the cuts have been deeper than those in Canada.

Goldman Sachs Group Inc. embarked on one of its biggest rounds of job cuts ever in January, when it moved to eliminate about 3,200 positions, amounting to 6.6 per cent of its workforce as of the end of last year. Morgan Stanley was also preparing a fresh round of about 3,000 cuts, Bloomberg reported in May, which came to about 5 per cent of staff excluding financial advisers and others in its wealth-management division. That came after it already trimmed its work force by about 2 per cent late last year.

Citigroup Inc. has also cut about 7,000 positions so far this year, its Chief Financial Officer Mark Mason said this month, though with a workforce that had swelled to 240,000, that represents just under 3 per cent, more in line with the cuts seen so far in Canada. Still, Citigroup is also preparing for more amid a strategic overhaul of the lender though it hasn’t put a number on the level of eliminations.

Canadian banks, like their U.S. peers, joined the scramble for technology and banking talent during the pandemic.

“Honestly, we overshot — we overshot by thousands of people,” RBC Chief Executive Officer Dave McKay told analysts in May.

After the wave of hiring, banks are now seeing lower attrition than usual thanks to the high level of economic uncertainty, Rizvanovic said.

Except for Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, all of the country’s big six banks reported negative operating leverage in the third quarter, meaning non-interest expenses grew at a faster clip than revenue. As they pledge to reverse that in 2024, they need to rein in costs.

HISTORIC PATTERN

There’s an incentive for them to get some of the cutting done now, as Scotiabank did last week, so that restructuring charges fall into the fiscal year that ends Oct. 31, which has already been a bad one. When the final numbers are in, five of the country’s six largest banks are expected to show annual declines in earnings per share, according to estimates compiled by Bloomberg.

The recent workforce reductions mark a return to a longstanding pre-pandemic pattern of trimming jobs before the end of October to start the following year with a lower cost base, according to Bill Vlaad, president of Toronto-based recruitment firm Vlaad & Co.

“Every year we sit on pins and needles between the 15th and 31st of October,” he said. “So the anxiety that’s there is not empty. There’s a history to back it up.”

CIBC, Toronto-Dominion Bank and National Bank of Canada haven’t publicly announced job cuts, but analysts have said they too could be looking at reductions. Rizvanovic also said much bank downsizing goes on behind the scenes through smaller trims that don’t demand public reporting.

“The banks are currently facing a challenging operating environment with slower loan growth, depressed capital markets and macroeconomic uncertainty,” said Carl De Souza, senior vice president and head of Canadian banking at DBRS Morningstar. “I think there are likely more cuts to come.”

Front-line tellers are at risk, De Souza said, noting that consumers now do much of their everyday banking online, and that branches are now tailored toward advice on mortgages and financial planning.

Vlaad doesn’t expect the banks to make “large changes in operational strategy,” but instead predicts strategic cuts in underperforming businesses. That’s what Canaccord Genuity did, making sizable cuts in its investment bank while leaving the more-stable wealth-management unit relatively unscathed.

Rizvanovic said targeted reductions may be ahead in capital-markets divisions and in areas where banks tend to hire consultants, such as technology.

Bank of Montreal and Scotiabank made big cuts and announced corresponding severance charges of C$162 million and C$247 million, respectively. But other banks may seek to avoid large announcements, Rizvanovic said, as they can raise concerns for both shareholders and the government at a time when Canada’s financial sector has increasingly become a political target amid a cost-of-living crisis.

“Optically, it might look bad,” he said, “if there’s this oligopoly of banks in Canada — that earns substantial returns on capital invested in the Canadian business, and billions of dollars in annual income — and they come out and say, ‘Well, we’re cutting staff.’”