As states and institutions come to terms with their historic roles in perpetrating slavery, new investigative reporting indicates that, today, the Chinese fishing sector is engaged in widespread enslavement of human beings. The question is: are we ready and willing to do something about it?

The New Yorker’s striking new investigation chronicles a pattern of human rights violations by the Chinese fishing sector – the largest in the world. These violations are happening not just within one company or on a single ship, but evidently, across the entire, largely state-run Chinese fleet.

By establishing the consistency and severity of these crimes, the reporting indicates this dynamic is not one of a few isolated matters of unfair labor practices or even human trafficking, but rather, the systematic exertion of ownership over the lives of human beings. That revelation brings the matter into the realm of slavery, and in doing so, raises a critical operational consideration for navies and coast guards around the world.

Trafficking versus Slavery

While many organizations have begun to refer to human trafficking as “modern slavery,” the two offenses, despite being almost impossible to distinguish on sight, are treated very differently by international maritime law.

Under Article 110 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, participating in slave trade is a crime of universal jurisdiction, meaning that it can be stopped by anyone outside of the territorial sea (the first 12 nautical miles from a state’s shore).

Labor violations and human trafficking, by contrast, are domestic offenses which can only be stopped within the territorial sea or by the law enforcement of the state whose flag a vessel is flying. This distinction, therefore, has major operational implications for enforcing these two different laws.

If a Chinese flagged vessel is suspected of having enslaved persons onboard, a ship from any country can board it anywhere outside of the territorial sea and check whether the people onboard are actually enslaved. That means, whether the vessel is 300 miles off Brazil or 12.1 miles off China, any state can stop slavery on that ship.

That is not true of human trafficking. If that same Chinese-flagged vessel is suspected of being involved in human trafficking, the only country that can board the ship and free the trafficked persons is China. And given that the examples found in the reporting all indicate either direct or indirect involvement by the Chinese state, that is likely never going to happen.

Abuses in Chinese Fishing Practices

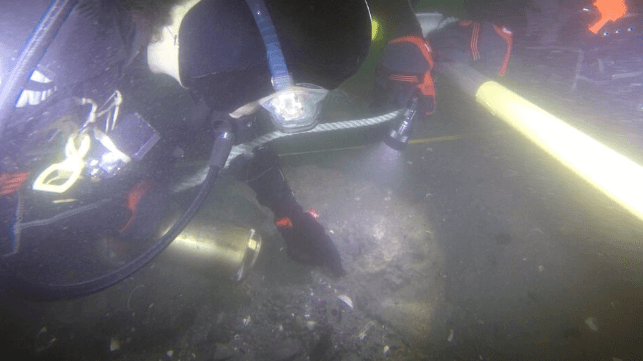

The Outlaw Ocean Project’s four-year investigation involved boarding Chinese fishing vessels all over the world. It revealed systematic treatment of workers on hundreds of these vessels that suggests the workers had no freedom. They had effectively become the property of the fishing companies such that even their access to life-saving medical treatment was at the discretion of their masters. The fish caught on many of those vessels then make their way to grocery stores and restaurants across Europe and North America, potentially rendering the global West complicit in this slavery.

Aside from the moral and geopolitical concerns surrounding these revelations, navies, coast guards, legislators, and criminal prosecutors should all be considering the maritime law enforcement implications of this new insight.

In isolation, most of The Outlaw Ocean Project’s revelations are discrete cases of human trafficking. Under international law, human trafficking has defined criteria including specific acts and means which lead to different forms of exploitation. When viewing the totality of the circumstances, however, it appears that the Chinese companies – often backed by the state – are actually exerting ownership over the lives of these fishers. That is how they can allow them to die, without consequences. They own their lives. Ownership is the key distinguishing factor between trafficking and slavery.

Limits of Existing Enforcement Regimes

But even if, based on the investigation’s revelations, Chinese vessels become suspected of participating in slavery, there is another problem. International treaties and conventions are not enough to take law enforcement action against the owners or operators of a vessel on which human beings are enslaved. The boarding state still needs domestic legislation that provides law enforcement jurisdiction outside of its territorial sea to not only disrupt the activity but detain that vessel and the people on it.

Furthermore, domestic law needs to provide a legal framework for prosecuting those individuals responsible for the crime of slavery. At present, even the states most vocal about slavery are not prepared to take jurisdiction over and prosecute actual cases of it. Many states will recognize this challenge when thinking back to counter-piracy efforts. Stopping pirates was the lesser challenge when compared with finding the legal basis to arrest and prosecute them in domestic courts.

While many around the world are concerned about the historical horrors of slavery, this new reporting reveals how pervasive it is in today’s maritime world. Sadly, however, the world’s navies, coast guards, and marine police forces are not ready to deal with this reality, legally or operationally. That needs to change quickly.

Hopefully, The Outlaw Ocean Project’s work will serve as a catalyst for doing so, by helping states recognize the need for both swift legislative action to ensure longarm statutes that criminalize slavery at sea and operational guidance to help their navies and coast guards identify and interdict this most reprehensible of crimes. If we are serious about universally condemning slavery, we must all be willing and able to actually do something about it.

Dr. Ian Ralby is CEO of I.R. Consilium, a family firm with leading expertise in maritime and resource security. A maritime lawyer by background, Dr. Ralby has worked in more than 90 countries around the world and is an advisor to various U.S. government agencies and international organizations. Dr. Ralby is also a Non-Resident Fellow at the Center for Maritime Strategy.

This article appears courtesy of the Center for Maritime Strategy and may be found in its original form here. The views expressed in this piece are the sole opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Center for Maritime Strategy or other institutions listed.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.