The Dangerously Appealing Style of the Far Right

The Forty-Eighth Newsletter (2023)

Emilio Pettoruti (Argentina), Arlequín (‘Harlequin’), 1928.

Emilio Pettoruti (Argentina), Arlequín (‘Harlequin’), 1928.

Before he won Argentina’s presidential election on 19 November, Javier Milei circulated a video of himself in front of a series of white boards. Pasted on one board were the names of various state institutions, such as the ministries of health, education, women and gender diversities, public works, and culture, all recognised as typical elements of any modern state project. Walking along the board, Milei ripped off the names of these and other ministries while crying afuera! (‘out!’) and declaring that if elected president, he would abolish them. Milei vowed not only to shrink the state but to ‘blow up’ the system, often appearing at campaign events with a chainsaw in hand.

The reaction to Milei’s viral video and other such stunts was as polarised as the Argentinian electorate. Half of the population thought that Milei’s agenda was madness, the sign of a far right out of touch with reality and rationality. The other half thought that Milei displayed precisely the kind of boldness required to transform a country mired in poverty and skyrocketing inflation. Milei did not just win the election; he won it handily, defeating the outgoing government’s finance minister, Sergio Massa, whose stale, centrist promises of stability did not sit well with a population that has lived with instability for decades.

Milei’s proposals to solve the downward spiral of the Argentinian economy are not unique, nor are they practical. Dollarisating the economy, privatisating state functions, and suppressing workers’ organisations are pillars of the neoliberal austerity agenda that has plagued the world for the past several decades. To debate Milei on this or that policy misses the point behind the ascendancy of the far right across the world. It is not what they say they will do to solve the world’s actual problems that matters so much as how they say it. In other words, for politicians like Milei (or Brazil’s former President Jair Bolsonaro, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and former US President Donald Trump), it is not their policy proposals that are attractive, but their style – the style of the far right. People like Milei promise to take the country’s institutions by the throat and make them cough up solutions. Their boldness sends a frisson through society, a jolt that masquerades as a plan for the future.

Fátima Pecci Carou (Argentina), Evita Ninja, 2020.

Fátima Pecci Carou (Argentina), Evita Ninja, 2020.

There was a time when the general mood of the international middle class centred on guaranteeing convenience: they hated the inconvenience of being stuck in traffic jams and queues, of being unable to get their children into the school of their choice, and of being unable to buy – even if by credit – the consumption goods that made them feel culturally superior to each other and to the working class. If the middle class was not inconvenienced, then that class – which shapes the electorate of most liberal democracies – would be content with promises of stability. But when the entire system convulses with inconveniences of one kind or another – such as inflation, the rate of which was 142.7% in Argentina at the start of the elections in October – then the assurance of stability holds little weight. The political forces of the centre, such as of Milei’s opponent, are trapped in a habit of speaking about stability while their country burns. They promise little more than incremental destruction. In this context, timidity is not always attractive to the middle class, let alone to workers and peasants, who require a bold vision rather than a fixation on mild cost-of-living increases alongside taxation holidays for big businesses.

This timidity is not merely about the character of the political force that seizes the moment. If that were the case, then merely shouting louder should win the centre-left and left votes. Rather, it reflects the increasing timidity of the centre-left and its political platform, deflated by the immense stresses and strains that have damaged society at the neurological level. The precariousness of employment, the state’s retreat from providing care for its people, the privatisation of leisure, the individualisation of education, and other strains have, together, produced overwhelming social problems (not to mention the impact of the climate catastrophe and brutal wars). The political horizon of large sections of the centre-left has been reduced to merely managing this decaying civilisation (as our latest dossier, What Can We Expect from the New Progressive Wave in Latin America?, points out). The persistent failure of governments to solve the problems of society has made politics itself foreign to large sections of the public.

Two generations of people have been raised in the world of austerity, sold falsehoods by technocratic experts who promise to improve their social condition through neoliberal economic growth. Why should they believe any expert who now cautions against the economic cannibalism promoted by the far right? Besides, the erosion of education systems and the reduction of the mass media into a gladiatorial contest have meant that there are few avenues for serious public discussion about the troubles facing our societies and the solutions needed to address them. Anything can be promised, anything can be implemented, and even when neoliberal agendas create catastrophic outcomes – as with Modi’s demonetisation scheme in India – they are touted as successes and their leaders are celebrated.

Neoliberalism has increased not only the precariousness of the global majority, but also sentiments of anti-intellectualism (the death of the expert and expertise) and anti-democratisation (the death of serious, democratic public education and discussion). In this context, Milei’s triumph is less about him than it is a product of a broader social process, one that is not exclusive to Argentina but holds true around the world.

Raquel Forner (Argentina), Mujeres del Mundo (‘Women of the World’), 1938.

Raquel Forner (Argentina), Mujeres del Mundo (‘Women of the World’), 1938.

Pillars of neoliberalism such as the privatisation and commodification of state functions created the social conditions for the rise of twin problems: corruption and crime. The deregulation of private enterprise and the privatisation of state functions have deepened the nexus between the political class and the capitalist class. Granting state contracts to private enterprises and cutting back on regulations, for instance, has provided immense avenues for bribes, kickbacks, and transfer payments to proliferate. Simultaneously, the increased precarity of life and the evisceration of social welfare increased the volume of petty crime, including through the drug trade (as demonstrated by a Tricontinental research project on the war on drugs and imperialism’s addictions, which will bear fruit soon).

The far right has fixated on these problems not in an effort to address the roots of the problem, but to achieve two results:

- By attacking the corruption of state officials but not of capitalist enterprises, the far right has been able to further delegitimise the state’s role as a guarantor of social rights.

- Using the general social malaise around petty crime, the far right has used every instrument of the state – which they otherwise decry – to attack the communities of the poor, garrison them under the guise of crime prevention, and rob them of any self-representation. This attack is extended against anyone who gives voice to the working class and the poor, from journalists to human rights defenders, from left politicians to local leaders.

The far right’s misleading representation and weaponisation of corruption and crime has placed the left at a deep disadvantage. On these issues, the far right has an intimate relationship with old social democracy and traditional liberalism, who generally accept the content of the far-right agenda, objecting only to their brash approach. This leaves the left with few political allies when it comes to these core battles, forcing it to defend the state form despite the corruption that has become endemic to it through neoliberal policy. Meanwhile, the left must continue to defend working-class communities from state repression, despite the real problems of crime and insecurity that confront the working class due to the collapse of employment and social welfare. The dominant debate is framed around the surface-level realities of corruption and crime and is not permitted to probe deeper into the neoliberal roots of these problems.

Diana Dowek (Argentina), Las madres (‘The Mothers’), 1983.

Diana Dowek (Argentina), Las madres (‘The Mothers’), 1983.

When the election results came in from Argentina, I asked our colleagues in Buenos Aires and La Plata to send me some songs that capture the current mood. Meanwhile, I buried myself in Argentinian poetry of loss and defeat, mostly the work of Juana Bignozzi (1937–2015). However, this was not the mood they wanted to put forward in this newsletter. They wanted something robust, something that reflects the boldness with which the left must respond to our current moment. This mood is captured by the rapper Trueno (b. 2002) and the singer Víctor Heredia (b. 1947), crossing generations and genres to produce the moving song Tierra Zanta (‘Sacred Earth’) and an equally moving video. And so, from Argentina:

I came into the world to defend my land.

I am the peaceful saviour in this war.

I will die fighting, firm as a Venezuelan.

I am Atacama, Guaraní, Coya, Barí, and Tucáno.

If they want to throw the country at me, we’ll lift it up.

We Indians built empires with our hands.

Do you hate the future? I come with my brothers and sisters

from different parents, but we don’t stay apart.

I am the fire of the Caribbean and a Peruvian warrior.

I thank Brazil for the air that we breathe.

Sometimes I lose, sometimes I win.

But it is not in vain to die for the land that I love.

And if outsiders ask what my name is,

my name is ‘Latin’ and my surname is ‘America’.

A New Mood in the World Will Put an End to the Global Monroe Doctrine

The Forty-Seventh Newsletter (2023)

Tagreed Darghouth (Lebanon), from the series The Tree Within, a Palestinian Olive Tree, 2018.

Tagreed Darghouth (Lebanon), from the series The Tree Within, a Palestinian Olive Tree, 2018.

Every day since 7 October has felt like an International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People, with hundreds of thousands gathering in Istanbul, a million in Jakarta, and then yet another million across Africa and Latin America to demand an end to the brutal attack being carried out by Israel (with the collusion of the United States). It is impossible to keep up with the scale and frequency of the protests, which are in turn pushing political parties and governments to clarify their stances on Israel’s attack on Palestine. These mass demonstrations have generated three kinds of outcomes:

- They have drawn a new generation not only into pro-Palestine activity, but into anti-war – if not anti-imperialist – consciousness.

- They have drawn in a new section of activists, particularly trade unionists, who have been inspired to stop the shipment of goods to and from Israel (including in places such as Europe and India, where the governments have supported Israel’s attacks).

- They have generated a political process to challenge the hypocrisy of the Western-led ‘rules-based international order’ to demand that the International Criminal Court indict Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and other senior Israeli government officials.

No war in recent years – not even the ‘shock and awe’ campaign used by the United States against Iraq in 2003 – has been as ruthless in its use of force. Most horrifying is the reality that civilians, penned in by the Israeli occupation, have no escape from the heavy bombardment. Nearly half (at least 5,800) of the more than 14,000 civilians that have been murdered are children. No amount of Israeli propaganda has been able to convince billions of people around the world that this violence is a righteous rejoinder for the 7 October attack. Visuals from Gaza show the disproportionate and asymmetrical nature of Israel’s violence over the past seventy-five years.

Vincent De Pio (Philippines), Back to the Future, 2012

Vincent De Pio (Philippines), Back to the Future, 2012

A new mood has taken root amongst billions of people in the Global South and been mirrored by millions in the Global North who no longer take the attitudes of US leaders and their Western allies at face value. A new study by the European Council of Foreign Relations shows that ‘much of the rest of the world wants the war in Ukraine to stop as soon as possible, even if it means Kyiv losing territory. And very few people – even in Europe – would take Washington’s side if a war erupted between the US and China over Taiwan’. The council suggests that this is due to the ‘loss of faith in the West to order the world’. More precisely, most of the world is no longer willing to be bullied by the West (as South Africa’s Foreign Minister Naledi Pandor put it). Over the last 200 years, the US government’s Monroe Doctrine has been instrumental in justifying this type of bullying. To better understand the significance of this key policy in upholding US dominance over the world order, the rest of this newsletter features briefing no. 11 from No Cold War, It Is Time to Bury the Monroe Doctrine.

n 1823, James Monroe, then president of the United States, told the US Congress that his government would stand against European interference in the Americas. What Monroe meant was that Washington would, from then on, treat Latin America and the Caribbean as its ‘backyard’, grounded by a policy known as the Monroe Doctrine.

Over the past 200 years, the US has operated in the Americas along this grain, exemplified by the more than 100 military interventions against countries in the region. Since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, the US and its Global North allies have attempted to expand this policy into a Global Monroe Doctrine, most destructively in Western Asia.

Stivenson Magloire (Haiti), Divided Spirit, 1989.

Stivenson Magloire (Haiti), Divided Spirit, 1989.

The Violence of the Monroe Doctrine

Two decades before Monroe’s proclamation, the world’s first anti-colonial revolution took place in Haiti. The 1804 Haitian Revolution posed a serious threat to the plantation economies of the Americas, which relied upon enslaved labour from Africa, and so the US led a process to suffocate it and prevent it from spreading. Through US military interventions across Latin America and the Caribbean, the Monroe Doctrine prevented the rise of national self-determination and defended plantation slavery and the power of the oligarchies.

Nonetheless, the spirit and promise of the Haitian Revolution could not be extinguished, and in 1959 it was reignited by the Cuban Revolution, which in turn inspired revolutionary struggles across the world and, most importantly, in the so-called backyard of the United States. Once again, the US initiated a cycle of violence to destroy Cuba’s revolutionary example, prevent it from inspiring others, and overthrow any government in the region that tried to exercise its sovereignty.

Together, US and Latin American oligarchies launched several campaigns, such as Operation Condor, to violently suppress the left through assassinations, incarcerations, torture, and regime change. These efforts culminated in a series of coups against left-wing forces in the Dominican Republic (1965), Chile (1973), Uruguay (1973), Argentina (1976), and El Salvador (1980). The military governments that were subsequently installed quashed the sovereignty agenda and imposed a neoliberal project in its place. Latin America and the Caribbean became fertile ground for economic policies that benefitted US-led transnational monopolies. Washington co-opted large sections of the region’s bourgeoisie, selling them the illusion that national development would come alongside the growth of US power.

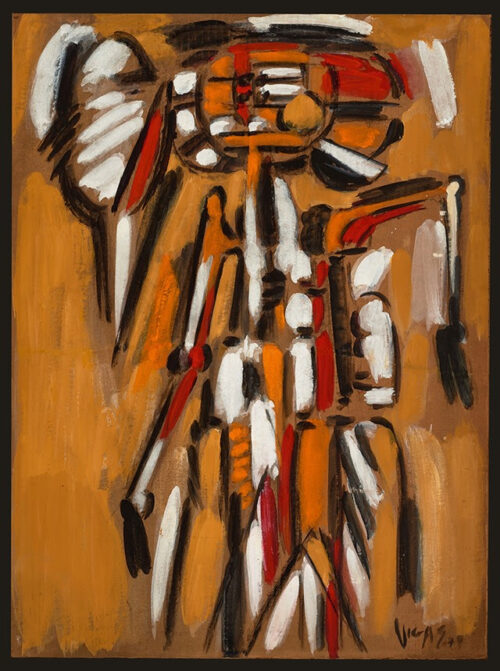

Oswaldo Vigas (Venezuela), Duende Rojo (‘Red Elf’), 1979.

Oswaldo Vigas (Venezuela), Duende Rojo (‘Red Elf’), 1979.

Progressive Waves

Despite this repression, waves of popular movements continued to shape the region’s political culture. During the 1980s and 1990s, these movements toppled the military dictatorships put in place by Operation Condor and then inaugurated a cycle of progressive governments inspired by the Cuban and Nicaraguan revolutions and propelled forward by the electoral victory of Hugo Chávez in Venezuela in 1998. The US response to this progressive upsurge was yet again driven by the Monroe Doctrine as it sought to secure the interests of private property above the needs of the masses. This counterrevolution has employed three main instruments:

1. Coups. Since 2000, the US has attempted to conduct ‘traditional’ military coups d’état on at least twenty-seven occasions, with some of these attempts succeeding, such as in Honduras (2009), while many others were defeated, as in Venezuela (2002).

2. Hybrid Wars. In addition to the military coup, the US has also developed a series of tactics to overwhelm countries that are attempting to build sovereignty, such as information warfare, lawfare, diplomatic warfare, and electoral interference. This hybrid war strategy includes manufacturing impeachment scandals (for example, against Paraguay’s Fernando Lugo in 2012) and ‘anti-corruption’ measures (such as against Argentina’s Cristina Kirchner in 2021). In Brazil, the US worked with the Brazilian right wing to manipulate an anti-corruption platform to impeach then President Dilma Rousseff in 2016 and imprison former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in 2018, leading to the election of far-right Jair Bolsonaro in 2018.

3. Economic Sanctions. The use of illegal, unilateral coercive measures – including economic sanctions and blockades – are a key instrument of the Monroe Doctrine. The US has employed such instruments for decades (since 1960 in the case of Cuba) and expanded their use in the twenty-first century against countries such as Venezuela. The Latin American Strategic Geopolitics Centre (CELAG) showed that US sanctions against Venezuela led to the loss of more than three million jobs from 2013 to 2017 while the Centre for Economic and Policy Research found that sanctions have reduced the public’s caloric intake and increased disease and mortality, killing 40,000 people in a single year while endangering the lives of 300,000 others.

Maya Weishof (Brazil), Between Talks and Myths, 2022.

Maya Weishof (Brazil), Between Talks and Myths, 2022.

End the Monroe Doctrine

US attempts to undermine progressive politics in Latin America, underpinned by the Monroe Doctrine, have not been entirely successful. The return of left-wing governments to power in Bolivia, Brazil, and Honduras after US-backed right-wing regimes illustrates this failure. Another sign is the resilience of the Cuban and Venezuelan revolutions. To date, while efforts to expand the Monroe Doctrine around the world have caused immense destruction, they have failed to install stable client regimes, as we saw with the defeat of US projects in Afghanistan and Iraq. Nonetheless, Washington remains undeterred and has shifted its focus to the Asia-Pacific to confront China.

Two hundred years ago, the forces of Simón Bolívar trounced the Spanish Empire in the 1821 Battle of Carabobo and opened a period of independence for Latin America. Two years later, in 1823, the US government announced its Monroe Doctrine. The dialectic between Carabobo and Monroe continues to shape our world, the memory of Bolívar instilled in the hope of and struggle for a more just society.

Sheena Rose (Barbados), Agony, 2022.

Sheena Rose (Barbados), Agony, 2022.

Today, the ugliness of the war on Gaza suffocates our consciousness. Em Berry, a poet from Aotearoa, New Zealand, wrote a beautiful poem on the name Gaza and the atrocities being inflicted upon its people by apartheid Israel:

This morning I learned

The English word gauze

(finely woven medical cloth)

comes from the Arabic word غزة or Ghazza

because Gazans have been skilled weavers for centuries

I wondered then

how many of our wounds

have been dressed

because of them

and how many of theirs

have been left open

because of us

Vijay Prashad is an Indian historian and journalist. Prashad is the author of twenty-five books, including The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World and The Poorer Nations: A Possible History of the Global South. Read other articles by Vijay, or visit Vijay's website.

Palestinians flock to Deir el-Balah beach in the central Gaza Strip, taking advantage of a pause in fighting between Israel and Hamas to bathe or fish © Mahmud Hams / AFP

Palestinians flock to Deir el-Balah beach in the central Gaza Strip, taking advantage of a pause in fighting between Israel and Hamas to bathe or fish © Mahmud Hams / AFP