RIGHT WING HAIR ON FIRE

Oxbridge dons hit out at claim British inventor stole his idea from slaves

HE PATENTED A PROCESS HE DID NOT INVENT IT....

Henry Cort (c 1741-1800) English iron founder who patented the pudding process for refining iron ore - Alamy© Provided by The Telegraph

Oxbridge dons have accused a rival scholar of “undermining the history of Britain” with “absolutely no evidence” in a row over claims that a key figure of the Industrial Revolution stole his idea from Jamaican slaves.

A leading academic journal has now launched a formal investigation after a history lecturer at University College London, Dr Jenny Bulstrode, claimed that Henry Cort, who is widely credited for inventing a groundbreaking new iron-making process in 1784, was not, in fact, responsible for the innovation.

Her paper, published in the prestigious journal History and Technology, said that his method for processing scrap iron into high-quality wrought iron was “theft...from Black metallurgists in Jamaica,” and his patent was “false mirrors for imperial eyes to picture themselves as they built their institutional lies”.

However, leading scholars have declared there is “absolutely no evidence” for the theory and accuse Dr Bulstrode of “ideologising history”. They have demanded that UCL investigates the “scandal”. Taylor and Francis, the publisher, has confirmed it has launched its own investigation.

Dr Bulstrode claims that a foundry in Jamaica was using grooved rollers to process scrap metal into wrought iron several years before Cort obtained his patent. She also argues that 76 black workers there were responsible for this innovation and that the foundry was demolished under a false pretext, with Cort conspiring for its machinery to be shipped for him to use in Portsmouth during the Industrial Revolution.

Dr Jenny Bulstrode© Provided by The Telegraph

Rival academics have trawled through the primary sources that Dr Bulstrode used and claim to have found misreadings, missing words, and evidence stating the contrary.

‘Almost a fairy tale’

Prof Lawrence Goldman, a leading historian at the University of Oxford, said the lecturer “constructed a story that is literally too good to be true…almost fairy tale’

“It’s serious, and evidence of how reason and facts are being suspended in the search for ever more ways to undermine the history of Britain and its empire,’ he told The Telegraph.

“We must give Jenny Bulstrode every chance to explain herself. We must also expect University College London, where she teaches, to investigate what has gone on, as, on the face of it, this is a serious infringement of academic conventions and the pursuit of historical truth,” he said.

English Historian Lawrence Goldman - David Rose© Provided by The Telegraph

In a rival academic article, Oliver Jelf, another history scholar, analysed Dr Bulstrode’s primary sources and said they showed ‘absolutely no evidence’ for the theory.

He said there was no evidence of grooved rollers ever existing at Reeder’s Pen, the foundry at Morant Bay in Jamaica established in 1772 by an Englishman, John Reeder, which forms the focal point of her thesis.

His paper also claimed that Cort’s relative John did not sail to Portsmouth and tell him about the foundry, as originally alleged, and the foundry was destroyed to fend off enemy troops - not under any pretext of “black retribution” as Dr. Bulstrode claimed - and no parts of the foundry were moved to Portsmouth afterward.

He also accused Dr Bulstrode of going “far beyond reasonable inference and veer[ing] into unsupported speculation” in interviews since the piece was published, on a podcast called The Context of White Supremacy.

A senior academic at Cambridge University, who wished to remain anonymous, said of the row: “The fundamental principle one has to abide by is ‘Plato is my friend but the truth even more,’ attributed to his young rival Aristotle.”

‘Multiple smoking guns’ required

Anton Howes, an expert in the history of innovation who has also considered the controversial paper, said: “Bulstrode’s narrative requires multiple smoking guns to work, none of which are in the evidence she presents… something that ought to have been picked up by the journal’s peer reviewers.”

Ageofinvention.xyz

Prof Goldman said that he thought the academic was “a victim of the system” which “encourages young researchers to choose certain types of subject, and, in order to stand out in the crowd, to reach surprising or even sensational conclusions, irrespective of the evidence,” with “any research that is in tune with academic fashion and the ‘zeitgeist’ is likely to be published and celebrated”.

A UCL spokesman said: “We are committed to maintaining and safeguarding the highest standards of integrity in all areas of research and take any allegations of researh impropriety very seriously. We understand the journal has launched a review process and we will await the outcome of this.”

A spokesman for Taylor and Francis said ‘there is currently an investigation into the criticisms being carried out by History and Technology and the Taylor & Francis Publication Ethics and Integrity Team, following our usual processes. Since that investigation is ongoing, we are not able to provide any further comment on the issue.’

Dr Bulstrode said: “My peer-reviewed research used a combination of shipping records, old newspapers and evidence in Jamaica, which are conventional methods of historical investigation.

“The comments raised are now being reviewed by the journal, and should I be asked, or where new evidence arises I will work with the journal to strengthen the evidence or add any addendums as is usual in academic discourse.”

Oxbridge scholars accused of 'white

domination' after defending Industrial

Revolution hero's legacy

Ewan Somerville

THE TELEGRAPH

18 November 2023

The editors of a prestigious academic journal have accused Oxbridge dons of “white domination” for defending a hero of the Industrial Revolution, The Telegraph can disclose.

A row ensued after History and Technology published an article by a University College London (UCL) lecturer claiming that Henry Cort, who is widely credited for inventing a groundbreaking iron-making process in 1784, had stolen his idea from Jamaican slaves.

The Taylor and Francis journal was forced to launch an investigation after The Telegraph revealed a series of critiques from leading Oxbridge historians showing there was “absolutely no evidence” for the claim by Dr Jenny Bulstrode of UCL, who called for reparations based on her paper.

Her research claimed that Cort’s method for processing scrap iron into high-quality wrought iron using grooved rollers was “theft...from Black metallurgists in Jamaica” who were using the method before his patent.

A rare correction has been issued for a source after Dr Bulstrode mistakenly claimed that Cort heard about an iron-making process at a Jamaican foundry via a ship led by Cort’s cousin John that sailed from there to Portsmouth when, in fact, it sailed to Lancaster, 280 miles away.

The incorrect claim was key to the argument that Cort stole his method from the foundry, Reeder’s Pen at Morant Bay in Jamaica. An unrelated ship, Princess Royal, sailed from Jamaica to Portsmouth without John Cort.

Another row has broken out after the journal’s editors suggested her critics are guilty of “profoundly selective historicism that support[s] white domination”.

The Oxbridge dons who initially raised concerns, along with other scholars, have now hit back at the journal for “pillaging” history for “present-day activism” and writing “gibberish”.

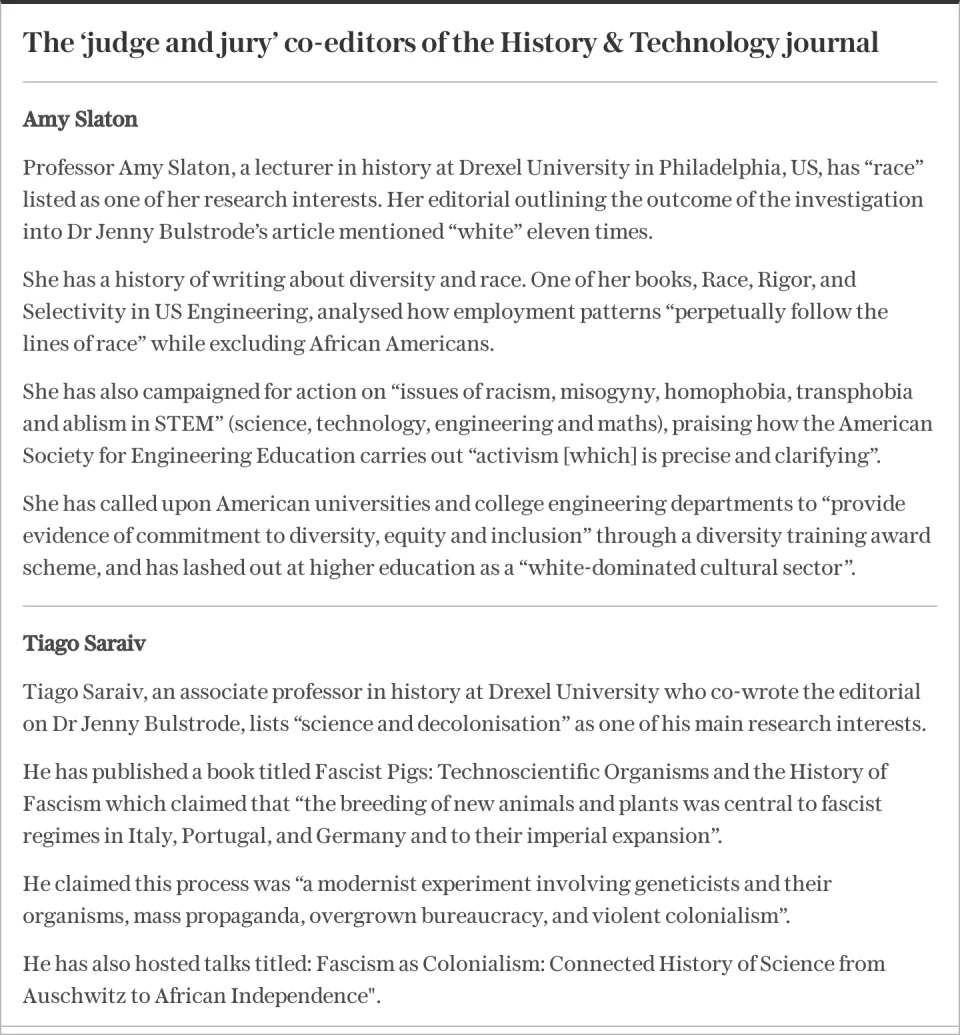

In a report outlining the findings of the investigation, Amy Slaton and Tiago Saraiv, the journal’s co-editors, made a series of incendiary swipes at Dr Bulstrode’s detractors, suggesting they take “narrow approaches to colonial-era sources” and of engaging in “particular race relations” by taking the view that “facts are facts”.

Henry Cort (c 1741-1800) English iron founder who patented the puddling process

They added: “As many scholars have shown, the primacy of white, EuroAmerican attainments in historical accounts of industrialisation -- corroborating the intellectual superiority of those dominant actors -- reflects the demographics of the history academy itself.”

The pair, both academics who write about colonialism at Drexel University in the US, backed Dr Bulstrode despite finding no new evidence to support her claims.

However, their investigation admitted that “there is no direct reference in any source quoted by Bulstrode or in the archaeological record to grooved rollers used to work iron at John Reeder’s foundry” and “the historical record does not provide again any immediate proof that Cort knew about what was going on at Reeder’s foundry”.

Professor Lawrence Goldman, a lecturer in modern history at the University of Oxford, told The Telegraph: “It provides no new evidence in support of Dr Bulstrode’s case. Indeed, in asking readers to assume and conclude things without evidence and on the basis of Bulstrode’s assertions, it only adds to the problems with her scholarship.”

He added: “They deny that facts exist... Indeed, their case seems to be that historical evidence is a tool of white oppression. It is contemptible that such arguments are deployed in a straightforward search for the empirical truth among historians.”

Professor Robert Tombs, a leading historian at the University of Cambridge, said: “The editors’ attempted justification shows that they do not see history as a means of understanding the past but of pillaging it for the use of present-day activism.”

‘Obfuscation, often buried in gibberish’

Professor David Abulafia, an expert in maritime history at the University of Cambridge, told The Telegraph: “Quite simply, we are entitled to know whether the facts are correct.

“What I therefore expected was a rigorous discussion of the contested points by an independent and neutral assessor. Instead, we have obfuscation, often buried in gibberish, from the editors of the very journal in which Dr Bulstrode’s article appeared. In the words of Lewis Carroll, ‘I’ll be judge, I’ll be jury’.”

A Taylor & Francis spokesman said it “took an impartial approach to the review, as we do in all such cases, with support from our Publishing Ethics and Integrity team”, adding: “Our record of corrections and retractions of published articles demonstrates that we are unafraid to take robust action when that is justified.”

Dr Bulstrode said: “My peer-reviewed research used a combination of shipping records, old newspapers, and evidence in Jamaica, which are conventional methods of historical investigation… The published editorial shows clear and unequivocal support for my research and methodology and commends the accuracy of the arguments and accounts I make.”

She added the correction on one of her sources “does not make any difference to the arguments in my paper”.

A UCL spokesman said: “As is evidenced by the review, Dr Jenny Bulstrode’s research provides a ‘considerable scholarly contribution’ to the field of history and technology, and she should be commended for the ‘deeply impactful’ nature of this work.”

AUTHORS Oliver Jelf

Introduction

Henry Cort is widely credited as the inventor of an improved method for processing

scrap iron into high-quality wrought iron, using a two-step process usually termed

rolling and puddling for which he obtained two patents: in 1783 (for rolling) and 1784

Cort is today widely considered one of the Industrial Revolution’s most important inventors, but details about his life are scant and almost nothing is known about the process by which he developed his rolling technique. The main primary source of information about Cort’s life is a collection of papers held in the Science Museum archive, which provides only the following short account

Illustrated London News,

25 October 1856, p. 430.

Abstract

This paper examines the available evidence relating to the disputed origin of Henry Cort’s

iron-rolling process. The principal primary sources, reproduced in the Appendix, do not

support the contention that Cort acquired the process from enslaved black metalworkers at

John Reeder’s foundry in Jamaica; nor that the foundry was dismantled and shipped to

Portsmouth for Cort’s benefit. The sources instead suggest that ordinary and widespread ironmaking processes were in use at Reeder’s foundry; that no innovation occurred there; that the chain of events by which Cort is supposed to have heard of the foundry’s activities certainly did not occur; that Reeder’s foundry was destroyed because of the threat of a Franco-Spanish invasion force; and that no part of the foundry was removed from the immediate vicinity of the island, let alone taken to Portsmouth

THE AMERICAN CONSERVATIVE

State of the Union: True and good historical research will

Sumantra Maitra

Oct 9, 2023

Can Academic History survive, at least in its current form? Or should it?

If you ask Joel Kotkin, the answer is a cautious maybe. Kotkin writes in an interesting essay, that:

History has moved to the front line of social conflict, but rarely has it been so poorly understood and sketchily taught. After decades of declining interest, only 13 percent of eighth graders achieve proficiency in the subject today. The New York Times reports that “about 40 percent of eighth graders scored ‘below basic’ in U.S. history last year, compared with 34 percent in 2018 and 29 percent in 2014.” This phenomenon can be seen across the West.

He adds that history is so neglected in the UK, that it has almost disappeared.

Study of the 19th century, meanwhile, seems to be vanishing from European classrooms. “We are in danger of mass amnesia, being cut off from knowledge of our own cultural history,” noted the late Jane Jacobs in her 2004 book, Dark Age Ahead. When I show my students a picture of Lenin, barely one-in-ten of them recognize it.

Kotkin isn’t the only one. My friend, David Randall of the National Association of Scholars, wrote something similar recently for the Martin Center.

“A continuing flow of conservatives into law and the judiciary has preserved a remnant body of tradition-minded law professors to make the case for originalism, natural law, and precedent. Tradition-minded political theorists also survive, as do tradition-minded economists. History departments, by contrast, have become almost entirely a left-wing preserve,” Randall observed, citing the 2016 study showing that the ratio of “Democrats to Republicans was 4.5:1 in economics, 8.6:1 in law, and 33.5:1 in history.”

Readers know that one of my pet peeves is the decline of academic history. I have written about that again and again in these pages, as well as in academic papers. I’d be a lot more sympathetic to the arguments that academic history departments 1) are actually producing good research, and 2) are providing everyone with decent jobs. Currently, they are doing neither. As a historian myself, I often tell starry-eyed young students that one shouldn’t go to study history as a profession unless one is independently wealthy and is interested in doing research out of a love for the subject, or is smart enough to have acquired a full doctoral scholarship, or already has a secured job offer in a related field—or preferably a combination of all three. There simply aren’t enough jobs for historians doing good history, and the academy doesn’t do good history anymore.

On the second point, consider the latest example: a “historian,” from a prestigious Russell Group university in Britain (the British version of the American Ivy+),

Last week, this newspaper disclosed how rival scholars had trawled through the primary sources Dr. Bulstrode based her theory upon and claimed there was no evidence of grooved rollers or a new iron-making method ever existing at Reeder’s Pen, the foundry at Morant Bay in Jamaica established in 1772 by an Englishman, John Reeder, which forms the focal point of her thesis.

Yet Jenny Bulstrode, the historian slash activist in question, is still arguing for “monetary reparations” for the “simultaneous theft and denial of black innovation.” She also blocked everyone on Twitter for pointing out that she is an utter imbecile who shouldn’t teach or be anywhere near a history department at a Russell Group university.

To argue that History departments at universities should or must survive after this is intellectually indefensible. In fact, one should start from the scratch. The academy is corrupted beyond reform. No good scholar will pass the ideological gatekeeping in academia. One cannot imagine a lowly uncredentialed historian simply observing and chronicling events or societies without any ideological color passing peer-review. It is therefore time to defund and destroy the ideological edifices and echo chambers before building new institutions. True and good historical research will survive meanwhile, outside the corrupt ivory towers—as has been the historic norm.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr Sumantra Maitra is a senior editor at The American Conservative and an elected, Associate Fellow at the Royal Historical Society.

The innovation, widely known as the "Cort process" after the English financier-turned-ironmaster who took credit for it, enabled scrap and poor-quality iron to be converted into wrought iron on an industrial scale.

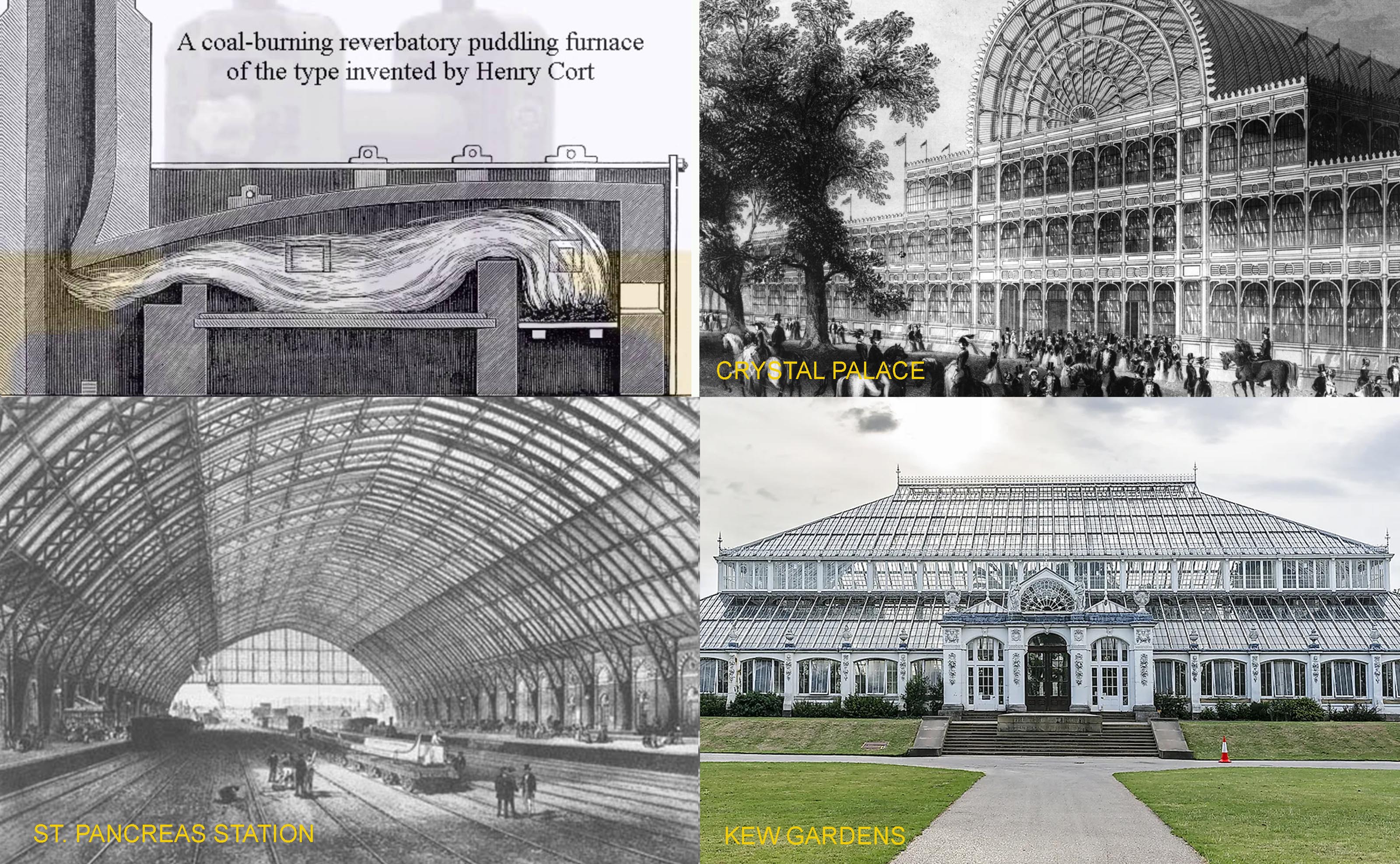

Profits from the innovation helped transform Britain into a global economic power, enabling British industries to manufacture and export everything from iron railways, iron ships, and iron engines to iron suspension bridges and iron factories. The method and its derivatives were even used to build "iron palaces" - famous structures such as Crystal Palace, Kew Gardens, and the archways at St Pancras International station.

The innovation was patented by Cort between 1783 and 1784, but in a new paper in the journal History and Technology, Dr Bulstrode shows how it was in use in a major iron works in Jamaica run by Black metallurgists several years before Cort’s patent. Many of these metal workers were enslaved people trafficked from West Africa and West Central Africa, home to some of the most important iron-working civilizations in world history.

The owner of the Jamaican iron works, a white enslaver called John Reeder, described himself as "quite ignorant of such a business" but how the Black metallurgists in his foundry were "perfect in every branch of the Iron Manufactory", and, through their skill, could turn scrap and poor-quality metal into valuable wrought iron.

Dr Jenny Bulstrode (UCL Science & Technology Studies), the author of the research, said: "The myth of Henry Cort needs to be revised. The so-called Cort process - one of the most important innovations in the making of the modern world - was developed by highly skilled Black metallurgists, most of whom were enslaved, for their own purposes. Recognition of the debt the British industrial revolution owes to Black innovation is long overdue."

The innovation combined two techniques: bundling scrap iron and heating it in a furnace that kept the metal separate from the heat source; and using grooved rollers, usually only found in sugar mills, instead of the smooth rollers conventionally used in European iron production. Bundled, heated and squeezed through the rollers in this way, the iron underwent a kind of mechanical alchemy that transformed it from worthless scrap into valuable metal. By 1781 the Jamaican iron works was making profit of £4,000 a year (equivalent to a relative annual income of £7.4 million in 2020 sterling).

While the Jamaican iron works turned spectacular annual profits, Henry Cort was facing bankruptcy. A financier from the age of 16, Cort took over the Portsmouth iron works of one of his clients in 1775 and laid out substantial sums to secure a contract to supply the Royal Navy’s iron work. He had hoped to make an easy profit, but soon found that he had contracted to trade the Navy’s old scrap iron for new, with no way of working up the old, rusted metal without making a loss.

Using shipping records and old newspapers, Dr Bulstrode’s research traces how Henry Cort learned of the Jamaican iron works from a visiting cousin, a West Indies ship’s master who regularly transported "prizes" - vessels, cargo and equipment seized through military action - from Jamaica to England.

In 1782, just a few months after Cort learned of the lucrative Jamaica foundry, the British government placed Jamaica under military law and ordered the iron works to be destroyed. The reason given in public was to prevent it falling into the hands of a rival power like France, Spain or Holland. In private, the military governor expressed the concern that if Black Jamaicans could convert scrap metal into cannon, then they could overthrow British colonial rule.

The foundry was razed to the ground, and the machinery and equipment from the works packed onto ships and transported to Portsmouth, where Henry Cort patented the innovation. The response in Britain was immediate. Politician John Baker Holroyd declared "our knowledge of the Iron trade seems hitherto to have been in its infancy" and, in direct reference to the loss of the American war and newly founded United States of America, described the so-called "Cort process" as being "more advantageous to Britain than Thirteen Colonies".

Five years later, Cort was discovered to have embezzled £39,676 of Navy’ wages. In response, the British government confiscated the patents and made them public, enabling the widespread uptake of the innovation among British iron works.

Jamaican expert in development and reparations, Dr Sheray Warmington (Honorary, UCL Science & Technology Studies), said the findings were important for the present reparations movement. "This isn’t just about sugar, tobacco and cotton. It’s about Black intellect and innovation which was robbed from the colonies and used to build the wealth of the global north of today. Again and again we see histories of the industrial revolution present Black people as machines. This story shows Black intellect was the driver of innovation and prosperity. Black intellect, that was stolen. It’s time that theft and the countless other innovations that were stolen from colonised countries are recognised by their former colonisers as a key tenant of the reparations movement."

Mark GreavesE: m.greaves [at] ucl.ac.ukUniversity College London, Gower Street, London, WC1E 6BT (0) 20 7679 2000

New historical research shows how the knowledge and skill of Black workers was stolen by a British entrepreneur.

DR. RUSSELL MOUL

Science Writer

The metallurgical process was crucial to the Industrial Revolution in Britain.

Image credit: Internet Archive Book Images via Flickr/Public domain

Henry Cort, a British entrepreneur born in Lancaster around 1740, has long been regarded as discovering a metallurgical technique that was crucial to the Industrial Revolution. However, a new study has shown that Cort actually stole the practice from Black metal smiths in Jamaica.

The traditional story

Cort is a somewhat unknown figure despite the impact his “discovery” had on the industrial world he was part of. We do know that he and his family were deeply embedded in the enslavement system which was a “staple” of Lancaster at the time. At a young age, Cort inherited a fortune and went on to have a successful career in finance. In 1775, he took over the ironworks of a naval officer client who was in debt. Although it was located within the Portsmouth dockyards, a prosperous site of industry, Cort struggled to break even and lost a substantial amount of money.

Then, five years later, he was approached by the Royal Navy for a contract to supply iron hoops for barrels. The contract was a poor one, however, as it required Cort to take on the Navy’s scrap iron and somehow turn it into a high-quality product that could be used for the hoops. At the time, there was no known way to do this; yet again, it looked like Cort would be at a loss. But suddenly, in 1783, Cort patented a new process where scrap iron could be heated in a modified furnace and fed through special grooved rollers.

Aspects of this technique were already in circulation among metallurgists, but no one had combined them in the way that Cort’s patent did. The metal was still impure, but it was nevertheless significantly stronger and could be used for much larger constructions than just barrel hoops.

Unfortunately for Cort, things did not go well. To fund his operations, Cort borrowed a considerable sum of money from Adam Jellicoe, a Navy employee who had actually embezzled Navy funds. Upon Jellicoe's death in 1789, Cort became liable for his debts, which forced him into bankruptcy. He quickly lost control of the patents, which was unfortunate for him but, so the story goes, a huge boon for British industry.

Now, his innovative technique was free to use by any budding industrialist and became the basis for suspension bridges, ship building, and textile mills.

The plot thickens

One of the enduring mysteries surrounding this story is how Cort apparently came up with his innovation. In 1783, he claimed that this novel approach was the result of “great study, labour, and expence [sic], in trying a variety of experiments and making many discoveries”. And yet there is no evidence of him undertaking any such experiments. It was like he had pulled the technique out of the air, but in reality, he had actually pulled it from across the Atlantic.

According to Jenny Bulstrode, a historian of science at University College London, Cort had stolen the idea from enslaved metal smiths in Jamaica.

During her research, Bulstrode found an archaeological report of a foundry in Jamaica that was using Cort’s technique before he apparently invented it. Through careful detective work, Bulstrode has now reconstructed a sequence of events that show how Cort had become aware of this foundry.

In 1772, John Reeder, an Englishman, established “Reeder’s Pen”, a lucrative foundry near Morant Bay in southeast Jamaica. This site produced boilers and rollers for the manufacturing of sugar and was manned by 76 Black metallurgists. In most instances, these workers had been taken from Africa by British slavers, but a few were Jamaican Maroons – individuals who had escaped slavery and preserved their freedom.

These Black metallurgists had perfected a method that allowed them to turn 3,000 tonnes of scrap iron into bars through furnaces and rollers. Crucially, the grooved rollers had been used for processing sugar cane but had never been used for iron.

According to Bulstrode, in the spring of 1781, Cort’s cousin John Cort visited Jamaica and was there at the time when one of the foundry workers was big news – a man named Kwasi, a Maroon, had killed a notorious freedom fighter called Three-Finger Jack. John would have certainly heard of this incident while he was there. Then, later that year, John’s ship experienced difficulties and headed to Portsmouth, where he met Henry.

Remember, Henry’s business was struggling at the time, and, coincidentally, so was Reeder’s Pen. It turns out that the foundry was actually illegal under British colonial law as anti-slavery rebels had used similar facilities to make weapons in the past. As such, in 1782, Reeder’s Pen was forced to shut down. But rather than disappearing from the world, the foundry was dismantled and shipped to Portsmouth.

“And the next thing you get is sugar rollers in Henry Cort’s foundry in Portsmouth," Bulstrode told New Scientist.

The story represents a significant example of why the history of science, and history more generally, should listen to the voices of under-represented actors. In this instance, the expertise of enslaved people played a crucial and hitherto under-appreciated role in the history of the Industrial Revolution. From this perspective, it also shows the extent to which the ideas and intellectual inputs of enslaved people could be claimed by their owners.

Increasingly, scholars are coming to appreciate the knowledge and expertise of these traditionally marginalized people. According to Bulstrode, the regions of west and west-central Africa where the British slave trade operated were also “some of the most significant iron-working regions in world history”.

The paper is published in History and Technology.

[H/T: New Scientist]

When the Brattle Group, engaged by the University of the West Indies, CARICOM Reparations Commission made its assessment of reparations to be paid in relation to Transatlantic Chattel Slavery, the United Kingdom was required to pay US$9.559 trillion in reparations to Jamaica.

But wait, there’s a twist! It seems that in their number-crunching extravaganza, the Brattle Group might have skipped a few pages in the history books. You see, Britain’s proud boast of being the world's top dog in fabricated iron export – thanks to something fancy called the “Cort Process” – actually owes a tip of the hat to enslaved African metallurgists in Morant Bay, Jamaica.

Who would have thought that the process that let them mass-produce wrought iron from scrap has its roots in a Jamaican foundry, not in some British chap's backyard.

Many Jamaicans were of the opinion that the ornate metal works which adorn the fencing and gates of many of our churches and Great houses came from Britain. Rather, according to the history, these elaborately decorasted wroughtn iron railings were fabricated by enslaved metallurgists from West Africa, right here in Jamaica.

Between 1783 and 1784 financier turned ironmaster Henry Cort patented the process of rendering scrap metal into a valuable iron bar . For this ‘discovery’, economic and industrial histories have lauded him as one of the revolutionary makers of the modern world.

“The process helped to launch Britain as an economic superpower and transformed the face of the country with “iron palaces”, including Crystal Palace, Kew Gardens’ Temperate House and the arches at St Pancras train station.”

Dr Jenny Bulstrode, a lecturer in history of science and technology at University College London (UCL), in a research paper entitled “Black metallurgists and the making of the industrial revolution” and published in History and Technology in June 2023, came across an intriguing revelation.

Many of these metalworkers were enslaved Africans trafficked from west and central Africa, which had thriving iron-working industries at the time.

These Black metallurgists in Jamaica, developed one of the most important innovations of the industrial revolution for their own cultural reasons.

According to Dr. Bulstrode, these metallurgists were taken from West Africa as a part of the Trans Atlantic Chattel Slave Trade.

“When the Feldkirch physician and trader, Hieronymus Münzer, visited Lisbon in late November 1494, he saw for himself that some of the most advanced ironworking technology in Europe depended on the skill of Black metallurgists.The king of Portugal had the best of everything, and that meant Black artisans in the royal ironworks,” Bulstrode said.

It is in light of this that she has focused on a “group of 76 Black metallurgists who ran an enslaver’s foundry, just west of Morant Bay, Jamaica.

There is rapidly growing literature on the contributions of artisans and healers of African descent to innovations historically credited to white practitioners and institutions in Northern Europe and North America.”

Dr. Bulstrode identifies the Black metallurgists in Jamaica as the authors of one of the most significant innovations of the British industrial revolution. “This innovation kicks off Britain as a major iron producer and … was one of the most important innovations in the making of the modern world.”

The latest research suggests that Cort shipped his machinery – and the fully fledged innovation – to Portsmouth from the Jamaican Morant Bay foundry that was forcibly shut down.

The Jamaican ironworks was owned by a white enslaver, John Reeder, who in correspondence described himself as “quite ignorant” of iron manufacturing, noting that the 76 black metallurgists who ran the foundry were “perfect in every branch of the iron manufactory”, and, through their skill, could turn scrap and poor-quality metal into valuable wrought iron.

Some of these workers are named in records, and include Devonshire, Mingo, Mingo’s son, Friday, Captain Jack, Matt, George, Jemmy, Jackson, Will, Bob, Guy, Kofi and Kwasi.

Their innovation came after the workers introduced the use of grooved rollers into the foundry to mechanize the formerly laborious process of hammering out impurities from low-quality iron. The same kind of grooved rollers were used in Jamaican sugar mills.

“It’s like a mechanical alchemy,” said Bulstrode. “You’re taking essentially rubbish and turning it into something of very high value through this process.”

When the newly appointed commander-in-chief of the fleet, Sir Chaloner Ogle, wrote from Port Royal, Jamaica, in May 1733, railing against ‘all Iron Works done by the People of this Island running the Government to vast Expense’, he referred to the contract system that underpinned much of the infrastructure of plantation production in the West Indies.

In this system a master workman would undertake a commission and then sub-contract the work to ‘his own people’: Black artificers both free and enslaved; and to Black artificers whose skilled working time he bought from another enslaver.

It was Jamaica’s Leeward Maroons, under the leadership of Kojo (Cudjoe), who first forced the British to the treaty in 1739. Just a few years later, a white observer reported on Kojo’s Leeward Maroons that “they forge their Own Iron Work, making Knives, Cutlasses, Heads of Lances, Bracelets ~ Rings & variety of other kind of necessaries; they have Bellows, made of Wood about six feet high & 16 inches thro’ which they make hollow and an hole at the Bottom thro’ which the Air Passes to the Fire, having for that purpose two [Maroons] who (with two more) are always working them up & down the hollow Wood by which means they have manufactured fire.

Taking the shackles, chains and agricultural implements of the enslavement system, Maroon metallurgists remanufactured them into ritual objects with the most powerful practical purpose. The knives and cutlasses that the observer reported were afana.

The Maroon word for a machete that is both the most mundane tool and mediator of the most dangerous sacred rites, afana directly recalls the Akan word for sword, ‘afena’.

The paper, published in the journal History and Technology, traces how Cort learned of the Jamaican ironworks from a visiting cousin, a West Indies ship’s master who regularly transported “prizes” – vessels, cargo and equipment seized through military action – from Jamaica to England.

Just months later, the British government placed Jamaica under military law and ordered the ironworks to be destroyed, and the foundry shut down, claiming it could be used by rebels to convert scrap metal into weapons to overthrow colonial rule.

“The story here is Britain closing down, through military force, competition,” said Bulstrode.

The machinery was acquired by Cort and shipped to Portsmouth, where he patented the innovation. Five years later, Cort was discovered to have embezzled vast sums from navy wages and the patents were confiscated and made public, allowing widespread adoption in British ironworks.

Bulstrode in challenging existing narratives of innovation said “If you ask people about the model of an innovator, they think of Elon Musk or some old white guy in a lab coat. “They don’t think of black people, enslaved, in Jamaica in the 18th century.”

Contributed

Dr. Jenny Bulstrode

JAMICIA GLEANER

Sunday | July 16, 2023

New research has shown that Jamaicans developed one of the most important innovations of the British industrial revolution. Now as global societies enter the fourth industrial revolution, the question is will they get the benefit of their achievements this time?

For centuries, historians have celebrated “the Cort process” as one of the 10- most-important innovations in the making of the modern world. Patented by British banker turned ironmaster, Henry Cort, between 1783 and 1784, the process made it possible to convert scrap metal into wrought iron on an industrial scale that could be used for everything from machinery and engines, to bridges and railways.

By the mid-19th century, the profits made from the innovation had helped transform Britain into a global power. The Times newspaper told its readers to thank the “Cort process” for raising British manufacturers “to the position of millionaires”, while the Royal Society’s leading metals expert declared: “It is scarcely possible to over-estimate the effect of Cort’s invention upon the material interests of this country and I may add of the world. Modern civilisation, I need not remind you, is due in no inconsiderable degree to cheap wrought iron and we owe cheap wrought iron to Henry Cort.”

It’s been called one of the 10-most-important innovations in the making of the modern world, but now new research has shown that the so-called “Cort process” was first developed in the 1770s by 76 black Jamaicans in a foundry just west of Morant Bay, Jamaica.

ABDUCTED

Many of these Jamaicans were born in Africa and abducted from some of the most significant iron-working cultures in world history. For them and for other Jamaicans of African heritage, the skill to turn European scrap into useful tools, weapons, and objects of art and beauty was very important. These Jamaicans took inspiration from the way many West and West-Central African societies bundled iron blades as currency, and from the work of bundling sugar cane. They tied plantation scrap iron into bundles and heated the bundles in a furnace where the fuel is kept separate from the metal.

In the European tradition, smooth rollers were used to roll metal, and grooved rollers were used to crush sugar cane. But these Jamaicans were unbothered by European conventions. They fed the bundles through grooved rollers like those only found in sugar mills and through this process ingeniously transformed scrap iron into cannon, sugar rollers and ships’ metal. Their innovation and skill made John Reeder, the British enslaver who owned the foundry, an annual profit equivalent to 1,423 million Jamaican dollars in 2020.

Among the Jamaicans who developed the process were enslaved men, Devonshire; Mingo; Mingo’s son; Friday; Captain Jack; Matt; George; Jemmy; Jackson; Will; Bob; Guy; Kofi (Cuffee); and a Windward Maroon called Kwasi (Quashie) from the original Nanny Town, the same Kwasi who killed the legendary freedom-fighter, Three Finger Jack, in 1781. In fact, it was through the death of Three Finger Jack that Henry Cort first heard about the Jamaican foundry.

Cort was a banker who had recently taken over an ironworks in Portsmouth, England, laying out a lot of money to win a contract to supply the Navy dockyard there. Cort had thought he would make an easy profit, but these hopes were dashed when he realised he had agreed to accept the Admiralty’s rusted scrap and exchange it for new metal. Instead of making a profit he found himself surrounded by scrap and no way of working it up without making a loss.

The banker-turned ironmaster was facing bankruptcy when his cousin, a West Indies ship’s master, arrived in Portsmouth with the latest news from Jamaica. Cort’s cousin told him how a Maroon named Kwasi had killed Three Finger Jack after taking the name of the owner of a major foundry, where black metallurgists had discovered a way to convert scrap into valuable new metal and huge profits.

Within a few months of their conversation, the British government had put Jamaica under martial law and ordered the destruction of the foundry. The public reason was that the foundry might fall into enemy hands. However, in private, the military governor warned the foundry was too dangerous, because if black Jamaicans could convert scrap metal into cannon, then they could undermine British manufacturers and overthrow British colonial rule.

WELL-CONNECTED

Cort was well-connected. He had been banker to the king of England’s brother and several other admirals, including the former commander-in-chief of the West India squadron. Pay agents like him regularly handled ‘prizes’ - the equipment, vehicles, vessels and cargo captured during armed conflict. His ship’s master cousin even transported prizes to England. With the foundry dismantled, its equipment was packed up and shipped to Portsmouth, where Cort operated.

Over the next two years, Cort patented the Jamaican innovation as his own. But he did not enjoy the profits for very long. In 1789 he was caught having embezzled Navy wages equivalent to 14,437 million Jamaican dollars in 2020. In response, the British government confiscated the patents.

This theft was nothing compared to the value of the innovation Cort stole from Jamaicans; and it is only one among many examples which are now being uncovered. The first British industrial revolution was founded on the stolen skill and knowledge of back people, the British government even enacted laws to prevent its colonies from competing with British manufacturers and to keep those countries as captive markets for British goods. Now as global societies enter the fourth industrial revolution and a new digital age, we must ask: will things be different this time?

Jamaican soils have been identified as a potential source of rare-earth minerals, crucial elements in the smartphones, laptops and other digital device that define the fourth industrial revolution. But will it be Jamaican people who benefit from this valuable resource? Or will this be another story of extraction and theft?

Jamaican skill and precision engineering developed what has been called one of the most important innovations in the first industrial revolution and the making of the modern world. Now we enter the fourth industrial revolution, that skill is long overdue recognition. Perhaps now is the time for the old colonial stories to be rewritten?

- Dr Jenny Bulstrode, is lecturer in history of science and technology at University College London, United Kingdom. Send feedback to j.bulstrode@ucl.ac.uk or columns@gleanerjm.com.

By Toby Paine

Published 8th Jul 2023,

Research from University College London (UCL) has brought Fareham’s industrial heritage and historic association with Henry Cort into question. Henry Cort patented ‘The Cort process’ in 1784 which allowed wrought iron to be mass-produced from scrap iron – he is celebrated as a maker of the modern world and was named the ‘Father of the Iron Trade’ after his death in 1800.

The legacy that surrounds Cort was branded a ‘myth’ in a recent paper authored by UCL lecturer Dr Jenny Bulstrode. The findings suggest that the technology was stolen from 76 Jamaican metallurgists ‘who developed one of the most important innovations of the industrial revolution’.

The paper traces how Cort shipped machinery from an ironworks in Morant Bay Jamaica to Portsmouth after the British government shut down foundries in the colony. Many of the 76 metalworkers were enslaved people trafficked from West and Central Africa where the technology originates.

Although he was born in Lancaster, Henry Cort took over an iron foundry in Funtley, a small village north of Fareham, in 1775.

Councillor Sean Woodward, leader of Fareham Borough Council, described the findings as ‘the industrial espionage of its day’.

‘It looks like he stole the technology from 76 Jamaican slaves,’ he said.

‘I suppose one could say he got his just deserts because when it turned out that the money he used for his business had been embezzled out of the Royal Navy he lost his patents and died destitute.

‘That was one person involved in the exploitation of the colonies who actually paid the price.

‘If there’s some great uproar that transpires I suppose we might contextualise Henry Cort because we’ve got a big ironwork exhibition and of course, we have Henry Cort Community College.

‘There’s Cort Drive where the school is and Henry Cort Way which is the Eclipse bus route – then there’s the millennial sculpture park.

‘The black in Fareham’s crest which is the background represents Fareham’s history in iron making and smelting.

‘The process revolutionised warfare and the industrial revolution – now somebody’s looked a little bit closer at where it actually came from.’

Dr David Andress, professor of modern history at the University of Portsmouth said the paper comments on a ‘wider sense’ that West and Central Africans had ‘enormous expertise’ in iron working ‘which Britain prides itself on’.

‘Europeans understood this from the middle ages,’ he added.

‘By the 1700s it’s clear that a lot of Africans were working as experts in metallurgical iron factories in these slave colonies.

‘That’s a real context in which to understand that certain kinds of innovation get patented in the British context and then become what is thought of conventionally as the narrative of the industrial revolution.

‘This extraordinary coincidence that is at the heart of the story, this plant in Jamaica which was working in this innovative way is demolished and shipped in parts to Portsmouth and then suddenly a year later Henry Cort patents that exact way of doing things.

‘There’s no smoking gun, he didn’t write a letter saying he stole it from Africans, but it would be an extraordinary coincidence if there wasn’t a connection.’

AUGUST 7, 2023

Download

Transcript

REGINA BARBER, HOST:

You're listening to SHORT WAVE...

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

BARBER: ...From NPR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

BARBER: The ability to create wrought iron cheaply has been called one of the most significant innovations in the British Industrial Revolution.

JENNY BULSTRODE: For most of the 18th century, British ironware is largely poor quality. It's brittle. It breaks easily. It even crumbles.

BARBER: But Dr. Jenny Bulstrode says that by removing impurities from iron, British industrialists were able to increase the strength of the metal. And she says that this process became known as the Cort process because of the English businessmen who popularized it - Henry Cort. And it gave way to all sorts of innovations in building frames, ships, engine boilers, you name it.

BULSTRODE: So Britain in the 18th century, in the 1700s, is more of an iron trader than an iron producer. There's this idea of Britain as the land of iron, but that's really what comes out of this process, actually.

BARBER: The process was considered by leaders in the British government to be, quote, "more advantageous to Britain than 13 colonies."

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

BARBER: But Jenny's latest research shines a light on how the iron process that once made Britain a superpower did not originate there. Cort stole it from a foundry of enslaved metallurgists in St. Thomas, Jamaica, a place that Dr. Sheray Warmington says isn't known for this work.

SHERAY WARMINGTON: It is a home to one of the more remarkable slave rebellions that took place in the country and, really, the Caribbean. And unfortunately, one of the parishes that many would see has fallen into not disrepair, but has not been given the proper acknowledgement that it deserves.

BARBER: She's a Jamaican expert in development and reparations in post-colonial states.

WARMINGTON: What has happened with St. Thomas - and Jenny mentions it in the paper - is that because of its locality and the resources in which it inhabits, a lot of resources were extracted from this parish.

BARBER: And Jenny says that it's precisely because these metallurgists were not European that they were able to make this huge innovation.

BULSTRODE: These are people who are very sophisticated in their science of metalworking, and they do something different with it than what the Europeans have been doing, because the Europeans are kind of constrained by their own conventions.

BARBER: Now Jenny and Sheray are partnering to make this history known.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

WARMINGTON: Our society, our people has helped to build the global norm for centuries. It is time for us to be recognized. It is time for repair, for our intellect to be recognized and acknowledged.

BARBER: Today on the show, we meet the Black metallurgists whose stolen discoveries revolutionize the world and hear about how these researchers are bringing attention to their legacy today. I'm Regina Barber. You're listening to SHORT WAVE from NPR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

BARBER: So, Jenny, before this process was introduced, iron in Britain was very brittle. How does this process that was created by Black metallurgists in Jamaica change that?

BULSTRODE: This process takes scrap iron and poor-quality iron that's brittle - it breaks easily - it even crumbles - and you bundle it together. You heat those bundles of iron in a specially designed kind of furnace, and then you feed the heated metal batch through grooved rollers. And what you produce is a metal with a tensile, elastic strength. And this process not only does this cheaply, but on an industrial scale. And that's really important.

BARBER: So then this guy, Henry Cort, comes to Jamaica and hears about it. Who is he? Like, why is he there?

BULSTRODE: Cort was a banker who went into the iron industry thinking he'd make a quick profit. By 1781, he was facing bankruptcy with a yard piled high with scrap iron and, in his words, no way of working it out without making a loss. And that's when his cousin, a merchant who shipped between Jamaica and Lancaster, told him about a foundry in Jamaica operated by 76 Black metallurgists who were turning scrap iron into wrought iron and making a profit equivalent to 7.4 million pounds sterling a year.

Now, Cort was a well-connected man. He had been banker to the King of England's brother. Within a few months, he had laid out massive sums of money. Jamaica was put under martial law, the foundry destroyed and its machinery and equipment packed up and shipped to Portsmouth, England, where Cort operated. It's very possible that some of the Black metallurgists were also taken to Portsmouth. They were described as perfect in every branch of the art and science of working metals. So they may well have been essential to this process and it's theft, in fact.

BARBER: Wow. So who exactly did Henry Cort steal this process from?

BULSTRODE: So he stole this innovation from 76 Black metallurgists in Jamaica. And we know some of their names - Devonshire, Mingo, Mingo's son, Friday, Captain Jack, Matt, George, Jemmy, Jackson, Will, Bob, Guy, Kofi and Kwasi. And we know these men were enslaved and likely born in Africa, abducted from some of the most important iron-working civilizations in world history, except Kwasi, who was likely of Akan heritage but born in Jamaica and a windward maroon. And in the Jamaican foundry, they worked together to apply new African and Jamaican ideas to old European technology.

BARBER: This is amazing. Sheray, can you tell us anything more about these ironworkers?

WARMINGTON: No, I don't have any more. And, you know, unfortunately, the records here for the enslaved Africans is very limited. And so we don't have that much more to say aside from, you know, where we suspect they come from - the areas in - on the African continent where they come from. And that's one of, you know, one of the saddest parts of, you know, at least Caribbean history, that we have such difficulty in tracing, you know, the legacies and the history of these individuals.

BARBER: Right. And what has been the response to learning this information in Jamaica today?

WARMINGTON: Well, we had, you know, two different kind of responses. You have historians who are very vocal who have said, you know, this isn't new. We, as historians, are fully aware that, you know, enslaved Africans have been innovating, have been developing and have produced an amazing - well, produced an amazing industrial complex. And it's because of their intellect and their knowledge why, you know, sugar production and colonialism and slavery was so successful for the Europeans. But then when you also look at the general public, there is also shock and disbelief because there is a lack of this information permeating through the education system and public knowledge. And so that is where the disconnect happens.

BARBER: OK. So I have to say, I was really surprised to hear this history. I didn't know anything about this iron process or the Black metallurgists. Why do you think more people need to know this story?

WARMINGTON: We need to start thinking about Black intellect and Black innovation in a new way. One of the issues that we discover and we realize when we talk about slavery and colonialism is this idea that - you know, that's constantly told to you that, you know, colonialism happened and slavery happened because, you know, the Europeans needed to help civilize the African continent; they needed to make them less barbaric and give them skills that would allow them to develop their own ways of life, when actually, when you look at it, they were the leaders in innovation and industry prior to slavery and colonialism. It gives our ancestors recognition and acknowledgement and it gives us identity, gives us a sense of purpose. So we need to be able to tell a story - a new story - of the Black enslaved Africans that is of hope, that represents them as human beings, that represents them as pathfinders, as heroes, as innovators, rather than just bodies on a plantation.

BARBER: For you two, what kind of change do you hope to see come out of this research?

BULSTRODE: I hope that people will be talking to experts like Sheray about what this means for education, for development, for reparations. I hope that it will be experts like Sheray taking this conversation forward, and I hope that this conversation will be going into schools, will be speaking to school children who are thinking about careers in science and technology and engineering and medicine. We know that Black academics and Black students are consistently underacknowledged for their achievements. They are consistently not given credit for the work that they do at the level that their white peers are given. I hope that this story will be part of changing the narrative around innovation to change that.

WARMINGTON: I think for us, when it comes at the grassroot level, we need to look at how history is taught in our schools. We need to involve more of these stories, more of these histories in how we, as a Caribbean community, teach history to the Black and brown students and to give them an opportunity to see where the true identity of their ancestors came from.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

BARBER: Thank you, Sheray; thank you, Jenny, both of you, for coming and sharing this story with us today.

BULSTRODE: Thank you so much for having us. It was a real privilege.

WARMINGTON: Thank you so much for allowing us to share this story.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

BARBER: This episode was produced by Carly Rubin and Berly McCoy, edited by managing producer Rebecca Ramirez and fact-checked by Brit Hanson. Robert Rodriguez was the audio engineer. Beth Donovan is our senior director, and Anya Grundmann is our senior vice president of programming. I'm Regina Barber. Thank you for listening to SHORT WAVE from NPR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

Copyright © 2023 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Hannah Devlin

@hannahdev

An innovation that propelled Britain to become the world’s leading iron exporter during the Industrial Revolution was appropriated from an 18th-century Jamaican foundry, historical records suggest.

The Cort process, which allowed wrought iron to be mass-produced from scrap iron for the first time, has long been attributed to the British financier turned ironmaster Henry Cort. It helped launch Britain as an economic superpower and transformed the face of the country with “iron palaces”, including Crystal Palace, Kew Gardens’ Temperate House and the arches at St Pancras train station.

Now, an analysis of correspondence, shipping records and contemporary newspaper reports reveals the innovation was first developed by 76 black Jamaican metallurgists at an ironworks near Morant Bay, Jamaica. Many of these metalworkers were enslaved people trafficked from west and central Africa, which had thriving iron-working industries at the time.

Dr Jenny Bulstrode, a lecturer in history of science and technology at University College London (UCL) and author of the paper, said: “This innovation kicks off Britain as a major iron producer and … was one of the most important innovations in the making of the modern world.”

The technique was patented by Cort in the 1780s and he is widely credited as the inventor, with the Times lauding him as “father of the iron trade” after his death. The latest research presents a different narrative, suggesting Cort shipped his machinery – and the fully fledged innovation – to Portsmouth from a Jamaican foundry that was forcibly shut down.

The Jamaican ironworks was owned by a white enslaver, John Reeder, who in correspondence described himself as “quite ignorant” of iron manufacturing, noting that the 76 black metallurgists who ran the foundry were “perfect in every branch of the iron manufactory”, and, through their skill, could turn scrap and poor-quality metal into valuable wrought iron.

Some of these workers are named in records, and include Devonshire, Mingo, Mingo’s son, Friday, Captain Jack, Matt, George, Jemmy, Jackson, Will, Bob, Guy, Kofi and Kwasi.

Their innovation came after the workers introduced the use of grooved rollers into the foundry to mechanise the formerly laborious process of hammering out impurities from low-quality iron. The same kind of grooved rollers were used in Jamaican sugar mills.

“It’s like a mechanical alchemy,” said Bulstrode. “You’re taking essentially rubbish and turning it into something of very high value through this process.”

By 1781, the Jamaican ironworks was turning an impressive profit of £4,000 a year, equivalent to about £7.4m today. Meanwhile, Cort was facing bankruptcy, after taking over a client’s ironworks in 1775 and laying out substantial sums to win a Royal Navy contract to process its scrap iron, before realising he stood to make a huge loss.

The paper, published in the journal History and Technology, traces how Cort learned of the Jamaican ironworks from a visiting cousin, a West Indies ship’s master who regularly transported “prizes” – vessels, cargo and equipment seized through military action – from Jamaica to England. Just months later, the British government placed Jamaica under military law and ordered the ironworks to be destroyed, claiming it could be used by rebels to convert scrap metal into weapons to overthrow colonial rule.

“The story here is Britain closing down, through military force, competition,” said Bulstrode.

The machinery was acquired by Cort and shipped to Portsmouth, where he patented the innovation. Five years later, Cort was discovered to have embezzled vast sums from navy wages and the patents were confiscated and made public, allowing widespread adoption in British ironworks.

Bulstrode hopes to challenge existing narratives of innovation. “If you ask people about the model of an innovator, they think of Elon Musk or some old white guy in a lab coat,” she said. “They don’t think of black people, enslaved, in Jamaica in the 18th century.”

Dr Sheray Warmington, an honorary research associate at UCL, said the work was important for the reparations movement: “It allows for the proper documentation of the true genesis of science and technological advancement and provides a starting point for how to quantify and repair the impact that this loss has had on the developmental opportunities of postcolonial states, and push forward the discourse of technological transfer as a key tenet of the reparations movement.”

University College London

Britain's industrial revolution was built on slavery, both Black labour and intellectual property, write Dr Jenny Bulstrode (UCL Science & Technology Studies) and Dr Sheray Warmington (Honorary, UCL Science & Technology Studies) in a piece for the Conversation.

In a speech to mark Unesco's campaign for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition, UN secretary-general António Guterres told the United Nations general assembly earlier this year that the inequalities created by 400 years of the transatlantic chattel trade persist to this day. "We can draw a straight line from the centuries of colonial exploitation to the social and economic inequalities of today," he said.

Guterres' words were echoed by Judge Patrick Robinson of the international court of justice, who has called for the UK to recognise the need to pay reparations for its part in the slave trade, telling The Guardian on August 22 that: "Reparations have been paid for other wrongs and obviously far more quickly, far more speedily than reparations for what I consider the greatest atrocity and crime in the history of mankind: transatlantic chattel slavery."

Investment into the trafficking of African people in the Caribbean created a lucrative economic system that helped Britain develop into a global economic superpower. The consequences continue to be felt today - not only in vast inequities in the distribution of wealth and resources, but also in the denial and effacement of the people of African descent whose skills and knowledge helped power that industrial and societal transformation.

This year marks the 240th anniversary of arguably one of the biggest thefts in the history of intellectual property. The so-called "Cort process", patented by the financier Henry Cort between 1783 and 1784, has been called one of the most important innovations of the British industrial revolution. Yet recently published findings show the process was first developed by 76 black metallurgists, many of them enslaved, in an 18th-century foundry in Jamaica.

The foundry was forcibly shut down for presenting too much of a threat to Britain's economic and political domination. We know some of these black metallurgists' names: Devonshire, Mingo, Mingo's son, Friday, Captain Jack, Matt, George, Jemmy, Jackson, Will, Bob, Guy, Kofi and Kwasi.

Stolen heritage

African enslavement may be considered one of the quintessential depictions of global theft and destruction in human history. In 2018, Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy's report on the restitution of cultural heritage pointed out that 90% of sub-Saharan Africa's material cultural heritage is held outside the continent. From the kidnapping of Africans from their homelands, the eradication of native populations, to the forced loss of African culture, history and identity, the damage that chattel enslavement has done continues to permeate development and economic discourse the world over.

But as the global reparations movement gains traction it opens a new discourse about the debt owed for that which was stolen. It also highlights the need to create a robust educational system aimed at highlighting the realities of slavery and colonialism. The history of the black metallurgists is just one example of the contributions of people of African descent to the wealth of European and US societies today.

For much of recent history, institutions in the global north have dominated the narrative of where and who drives innovation. But history - and history taught in schools - must also recognise and name enslaved Africans as true innovators of their times. In Florida, the governor and Republican presidential hopeful, Ron DeSantis, has introduced new educational standards which teach that some enslaved people benefited from slavery. History must challenge this constant narrative of black bodies merely being machines.

Truth and reparation

In the search for truth and reparation, truth of brutalities inflicted alone is not enough. There must also be truth about the pioneers and innovators of colonised and enslaved societies - such as the 76 black metallurgists - whose ideas changed the trajectory of civilisation and who laid the building blocks for growth, change and development.

The simultaneous theft and denial of black innovation has served a purpose for the global north. The Caricom Reparations Commission, notes that one of the main policies of the European colonisers was that there should be "not a nail to be made in the colonies". A fundamental part of the global north's accumulation has been to create captive markets and maintain those markets post-independence. Colonies and post-independence states alike have been actively deprived of the developmental apparatus to create a thriving society.

Resource extraction during this period was not merely centred on sugar, tobacco and cotton. It also drew on intellect and innovation which was stolen from the colonies and used to help build the prosperous nations of the global north.

Reparation is not only about money. It is also about recognition. Alongside the names of freedom fighters such as Sam Sharpe and Queen Nanny, children must learn the names of black innovators. Part of truth and reconciliation must be this re-centring of black identity as part of a decolonised education system across former colonial and colonising states.

It must be a curriculum which includes the names and identities of enslaved African people whose skill and knowledge both challenged and transformed the global industrial and economic system. Through this, descendants will gain an understanding of the importance of their own history and ancestral cultures and all it contributed.

Recognition of the theft of black intellectual property provides a starting point for quantifying the harms that were done and continue to resonate to this day. This is necessary for any process of truth and reconciliation.

Quantification and monetary reparation, while necessary, are not in themselves enough. They must be combined with institutional recognition through an education system that acknowledges the role of enslaved African people in both challenging and driving forward the economies, scientific innovations and cultures of European enslavers.

/Public Release. This material from the originating organization/author(s) might be of the point-in-time nature, and edited for clarity, style and length. Mirage.News does not take institutional positions or sides, and all views, positions, and conclusions expressed herein are solely those of the author(s).

In a speech to mark Unesco’s campaign for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition, UN secretary-general António Guterres told the United Nations general assembly earlier this year that the inequalities created by 400 years of the transatlantic chattel trade persist to this day. “We can draw a straight line from the centuries of colonial exploitation to the social and economic inequalities of today,” he said.

Guterres’ words were echoed by Judge Patrick Robinson of the international court of justice, who has called for the UK to recognise the need to pay reparations for its part in the slave trade, telling The Guardian on August 22 that: “Reparations have been paid for other wrongs and obviously far more quickly, far more speedily than reparations for what I consider the greatest atrocity and crime in the history of mankind: transatlantic chattel slavery.”

Investment into the trafficking of African people in the Caribbean created a lucrative economic system that helped Britain develop into a global economic superpower. The consequences continue to be felt today – not only in vast inequities in the distribution of wealth and resources, but also in the denial and effacement of the people of African descent whose skills and knowledge helped power that industrial and societal transformation.

This year marks the 240th anniversary of arguably one of the biggest thefts in the history of intellectual property. The so-called “Cort process”, patented by the financier Henry Cort between 1783 and 1784, has been called one of the most important innovations of the British industrial revolution. Yet recently published findings show the process was first developed by 76 black metallurgists, many of them enslaved, in an 18th-century foundry in Jamaica.

Join thousands of Canadians who subscribe to free evidence-based news.Get newsletter

The foundry was forcibly shut down for presenting too much of a threat to Britain’s economic and political domination. We know some of these black metallurgists’ names: Devonshire, Mingo, Mingo’s son, Friday, Captain Jack, Matt, George, Jemmy, Jackson, Will, Bob, Guy, Kofi and Kwasi.

Stolen heritage

African enslavement may be considered one of the quintessential depictions of global theft and destruction in human history. In 2018, Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy’s report on the restitution of cultural heritage pointed out that 90% of sub-Saharan Africa’s material cultural heritage is held outside the continent. From the kidnapping of Africans from their homelands, the eradication of native populations, to the forced loss of African culture, history and identity, the damage that chattel enslavement has done continues to permeate development and economic discourse the world over.

But as the global reparations movement gains traction it opens a new discourse about the debt owed for that which was stolen. It also highlights the need to create a robust educational system aimed at highlighting the realities of slavery and colonialism. The history of the black metallurgists is just one example of the contributions of people of African descent to the wealth of European and US societies today.

For much of recent history, institutions in the global north have dominated the narrative of where and who drives innovation. But history – and history taught in schools – must also recognise and name enslaved Africans as true innovators of their times. In Florida, the governor and Republican presidential hopeful, Ron DeSantis, has introduced new educational standards which teach that some enslaved people benefited from slavery. History must challenge this constant narrative of black bodies merely being machines.

Truth and reparation

In the search for truth and reparation, truth of brutalities inflicted alone is not enough. There must also be truth about the pioneers and innovators of colonised and enslaved societies – such as the 76 black metallurgists – whose ideas changed the trajectory of civilisation and who laid the building blocks for growth, change and development.

The simultaneous theft and denial of black innovation has served a purpose for the global north. The Caricom Reparations Commission, notes that one of the main policies of the European colonisers was that there should be “not a nail to be made in the colonies”. A fundamental part of the global north’s accumulation has been to create captive markets and maintain those markets post-independence. Colonies and post-independence states alike have been actively deprived of the developmental apparatus to create a thriving society.

Resource extraction during this period was not merely centred on sugar, tobacco and cotton. It also drew on intellect and innovation which was stolen from the colonies and used to help build the prosperous nations of the global north.

Reparation is not only about money. It is also about recognition. Alongside the names of freedom fighters such as Sam Sharpe and Queen Nanny, children must learn the names of black innovators. Part of truth and reconciliation must be this re-centring of black identity as part of a decolonised education system across former colonial and colonising states.

It must be a curriculum which includes the names and identities of enslaved African people whose skill and knowledge both challenged and transformed the global industrial and economic system. Through this, descendants will gain an understanding of the importance of their own history and ancestral cultures and all it contributed.

Recognition of the theft of black intellectual property provides a starting point for quantifying the harms that were done and continue to resonate to this day. This is necessary for any process of truth and reconciliation.

Quantification and monetary reparation, while necessary, are not in themselves enough. They must be combined with institutional recognition through an education system that acknowledges the role of enslaved African people in both challenging and driving forward the economies, scientific innovations and cultures of European enslavers.

Lecturer in History of Science and Technology, UCL

Honorary Research Associate, UCL

We believe in the free flow of information

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under Creative Commons licence.

In July 2023 Dr Jenny Bulstrode published an article entitled ‘Black metallurgists and the making of the Industrial Revolution’ in the refereed journal History and Technology. Since then the author has been subject to sustained abuse in newspapers and on social media, sparking a campaign of personal vilification. The detailed and wide-ranging evidence the article accumulates concerning Black metallurgists’ material cultures in relation to key innovations has been curtly dismissed by critics. These attacks by a small group of people have neglected both common courtesy and established academic standards, including principles of peer review.

History and Technology, whose editors are acknowledged historians of colonialism and race, has just issued a rigorous review

In our view, the treatment of the paper and its author is clearly connected to its topic, which involves the enterprises of enslaved peoples, people of colour, and other individuals and groups who have long been ignored, marginalised and misrepresented by past historical studies.

We strongly condemn unwarranted attacks on authoritative and innovative research of any kind.

By Alexander Stoeger|November 22nd, 2023|BSHS Announcements,

Date:27/10/2021

unimelb.edu.au

Event Details

Performances on the World Stage: Interpreting innovation in iron ‘in the light of what is old’

For his ‘discovery’ of a process that could turn maritime scrap into valuable metal, the financier turned ironmaster Henry Cort was martyred in the final years of the eighteenth century; canonized in the nineteenth; and, in the ultimate apotheosis of capitalist cosmology, dubbed one of ten ‘macro-inventors’ in the early twenty-first: a demi-urge of progress. This deification is not a metaphor. It is a literal account of how Cort and the ‘heroes of invention’ came to be treated in a particular tradition of industrial and economic triumphalism. The construction of the myth has been well documented, but somehow the idea persists. To paraphrase Marshall Sahlins on despondency theory, here, efforts to move beyond the representation of the same convention-dominating groups seem to collapse under the shattering impact of global capitalism. This lecture proposes Greg Dening’s seminal Performances as the apposite analytical framework for the apotheosis of Cort. Following Dening’s injunction to interpret ‘what is new in the light of what is old’, it argues Cort’s ‘discovery’ was the theft of crucial techniques derived from West African traditions and developed by Black metallurgists in Jamaica. The decisive moment of technological transfer: a death that became performances in an encounter between cultures.

About Dr Jenny Bulstrode

Before joining UCL’s Department of Science and Technology Studies in 2020, Jenny began a Junior Research Fellowship at the University of Cambridge, researching histories of globalisation and the displacement of Indigenous industries and sustainable practices. During her doctoral research, awarded 2020, she held both Caird and Sackler research fellowships, respectively considering cultural and technical histories of metal. Awards for her published work on living copper, whaling iron, springing glass and knapping flints include: a 2020 Maurice Daumas Prize; the 2018 American Academy of Arts and Sciences Sarton Prize and the 2014 British Society for the History of Science Singer Prize.

About the Greg Dening Lecture

Emeritus Professor Greg Dening (1931-2008) occupies an important place in the history of the History program at the University of Melbourne. As Tom Griffiths put it, 'Greg was not only a wonderful historian but also a gifted teacher, and he believed that immersion scholarship could be transformative -- of oneself, and also of the world... In his hands, history was no mere subject at university; it became a form of consciousness, a definition of humanity, a way of seeing -- and changing -- the world.' (History Workshop Journal 67:1 (Spring 2009)). We remember Greg Dening through this annual memorial lecture, the text of which is published in Melbourne Historical Journal, and through an annual Greg Dening Memorial Prize, generously supported by the SHAPS Fellows and Associates Group.

JAN 30, 2019

History of Science Prize to Jenny Bulstrode:

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences has named Jenny Bulstrode the recipient of the 2018 Sarton Prize for History of Science in recognition of her achievement and promise as an emerging scholar in the field.

Jenny Bulstrode is a doctoral student and researcher at the Department of History and Philosophy of Science, Cambridge (HPS) and National Maritime Museum, Greenwich (NMM). She was awarded the Singer Prize for her work on the relationship between archaeology, manufacture, and the industrial society of mid-Victorian Britain, which was published by The British Journal for the History of Science.