EK Janaki Ammal: The 'nomad' flower scientist India forgot

GEETA DOCTOR

GEETA DOCTORIn March, the magnolias begin blooming at Wisley.

For the next few weeks, rows of pink flowers dot the small town in Surrey in the UK, beckoning passers-by to stop and smell them.

Few know, however, that many of these blooms have Indian roots.

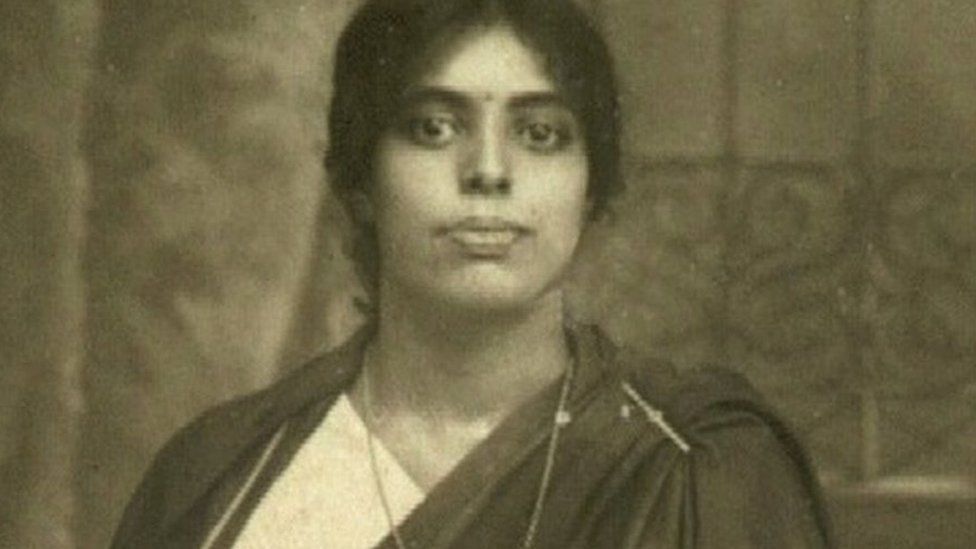

They were planted by EK Janaki Ammal, a scientist who was born in the southern Indian state of Kerala in the 19th Century.

In a career spanning almost 60 years, Janaki studied a wide range of flowering plants and reworked the scientific classification of several families of plants.

"Janaki was not just a cytogeneticist - she was a field biologist, a plant geographer, a palaeobotanist, an experimental breeder and an ethno-botanist and not in the least, an explorer," says Dr Savithri Preetha Nair, a historian who has researched the scientist's life for years.

It's difficult, Dr Nair says, to name even one Indian male geneticist from the time who adopted such cross-disciplinary methodology in their research.

"She talked about biodiversity as early as the 1930s."

Janaki lived an inspiring life, but for decades, her work went largely unappreciated and her contribution to science was barely acknowledged.

But this year - which also marks Janaki's 125th birth anniversary - Dr Nair hopes to change that with an in-depth biography. The book, titled Chromosome Woman, Nomad Scientist: E.K. Janaki Ammal, A Life 1897-1984, was released earlier in November and is the product of 16 years of research spread across three continents.

It also marks, Dr Nair says, the beginning of "a grand project" of recovering stories about Indian women in science.

"Until now, published sources on women scientists have focused on Europe and North America," she says, adding that women from Asia and other regions "hardly figure anywhere".

COURTESY OF THE JOHN INNES FOUNDATION

COURTESY OF THE JOHN INNES FOUNDATIONAn extraordinary life

While Janaki's professional achievements were numerous, her family members say the way she lived her life was also inspiring.

"She thrived on human possibility," says Geeta Doctor, a writer and Janaki's grand-niece. "She was passionate about everything, completely liberated and always fixated on her work."

Janaki was born in Tellichery (now Thalassery) in Kerala in 1897. Her father, EK Krishnan, was a high court sub-judge in the Madras Presidency, an administrative subdivision in British India.

She grew up in privilege, in a large family that lived in a house called Edam, which Ms Doctor says was "the centre of Janaki's life".

The two-storey house had a grand piano, a sprawling library and spacious halls, its large windows overlooking a carefully-tended garden.

Janaki belonged to Kerala's Thiyya community, which is regarded as socially backward under the Hindu caste system.

But at Edam house, Janaki's life was far removed from any prejudices, Ms Doctor says.

That didn't mean she did not face caste discrimination in her life, she adds - but she never allowed it to stop her.

"If somebody displeased her, she would just move on."

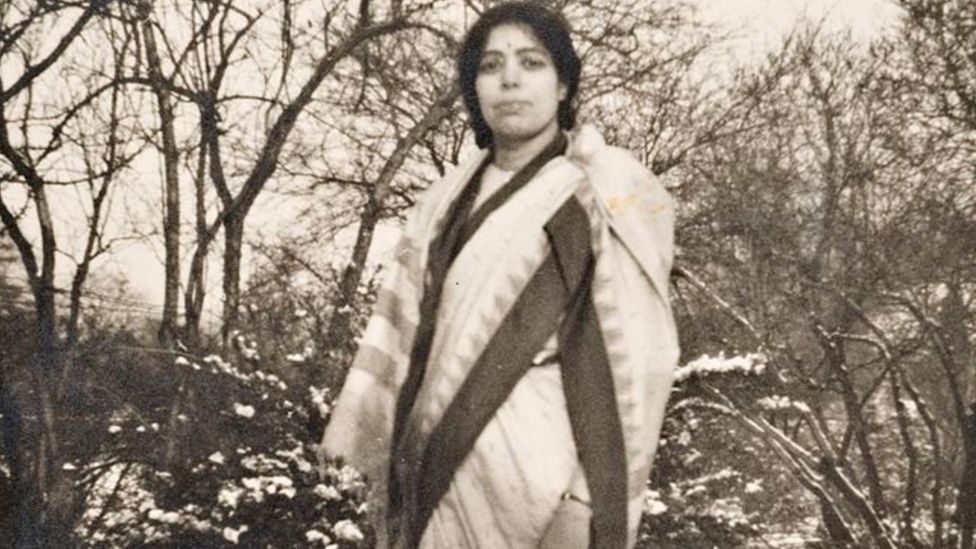

GEETA DOCTOR

GEETA DOCTORTouch of sweetness

After she finished school, Janaki moved to Madras (now Chennai) for higher education.

In 1924, she was teaching at a women's college when she received a prestigious scholarship from the University of Michigan in the US.

Eight years later, she became the first Indian woman to be awarded a doctorate in botanical science.

She returned to India shortly after, and taught botany in her home state before joining the Sugarcane Breeding Station at Coimbatore.

It was here that Janaki worked on cross-breeding sugarcane and with other plants to create a high-yielding variety of the crop that could flourish in India.

She was the first person to successfully cross sugarcane and maize, which helped in understanding the origin and evolution of sugarcane, Dr Nair says.

A particular hybrid she created, the historian adds, went on to produce many commercial crosses for the institute but she didn't receive credit for it.

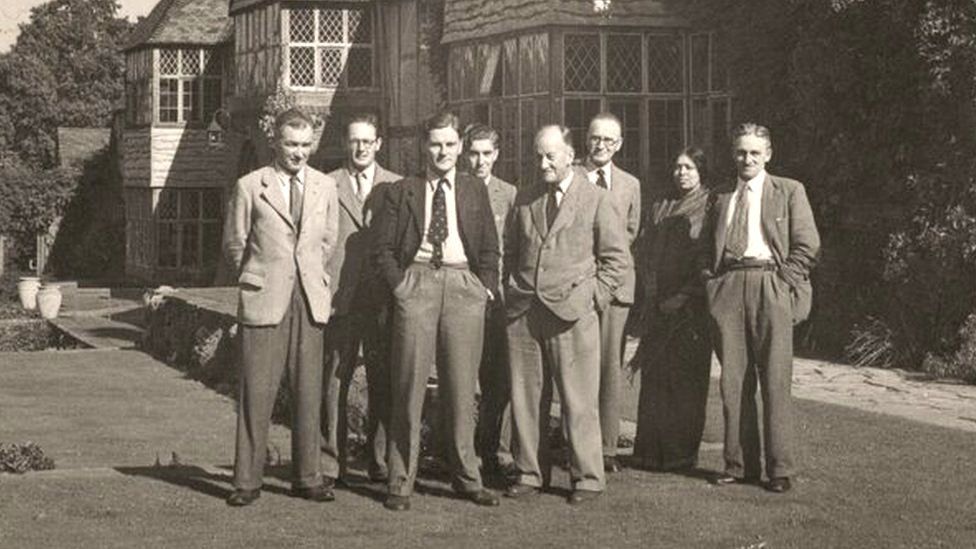

In 1940 - just after World War Two had started - Janaki moved to London and joined the John Innes Horticultural Institution to continue her research.

The next few years were the most formative ones of her career. Five years later, she became the first woman scientist to be employed at the Royal Horticultural Society Garden at Wisley.

It was also a time of hardships and hard work - Britain was facing the brunt of the war and food supplies were heavily rationed.

"But Janaki was unfazed," Ms Doctor says. "When the bombs fell, she would just dive under the table or sleep under the bed - all in a day's work."

COURTESY OF THE RHS LINDLEY COLLECTIONS

COURTESY OF THE RHS LINDLEY COLLECTIONSThis attitude extended to her personal life, she says.

"[The children of her family] were her equals and she expected us to keep up with her strict ways."

But there was a sweeter side to her as well.

Ms Doctor recalls that her grand-aunt gave them amazing books and took them on delightful picnics.

And she was always brimming with stories - about Kapok, the small black-striped palm squirrel that she had smuggled in her sari to keep her company in London; and her doll Timothy, who fascinated everyone at Edam.

Ms Doctor does not put dates to these memories - the past is simply the past - but she vividly remembers Janaki's strident personality and commanding presence; her vibrant yellow saris; and her "energetic yet subtle" ways.

"She enjoyed life in its minutiae and also the grand scheme of things, but with a rigorous scientific mind."

Dr Nair says that this was also evident in her work, which was not about one seminal revelation, but a series of small-scale discoveries which contributed "to the grand history of human evolution".

"The questions she asked were fundamental ones about plants and man."

COURTESY OF THE RHS HERBARIUM

COURTESY OF THE RHS HERBARIUMHomecoming

In 1951, India's prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru asked Janaki to return to the country and help restructure the Botanical Survey of India (BSI).

Janaki, who was greatly inspired by the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi, went immediately.

"But her male colleagues refused to take commands from a woman and her attempts to re-organise BSI were turned down," Dr Nair says, adding that Janaki was never entirely accepted at the institute.

This caused her great pain and she could never entirely recover from it. So she took refuge in exploring the country in search of new plants.

In 1948, Janaki became the first woman to go on a plant-hunting expedition to Nepal which, according to her, was the most unique part of Asia botanically, says Dr Nair.

When she was 80, the Indian government awarded her a Padma Shri, one of the country's highest civilian honours. She died seven years later, in 1984.

Ms Doctor says that even though Janaki did not receive the recognition she deserved, she never lost her passion for studying life.

"She would always say 'my work will survive' - and it did."

Dr Nair agrees.

"Janaki's life continues to be a blazing testament to intellectual integrity."