E-scooters are linked with injuries and hospital visits, but we can't say they are riskier than bikes yet

FEBRUARY 4, 2024

E-scooters are a popular new feature of urban mobility, offering an eco-friendly solution with zero exhaust emissions and agility in city spaces. They make an attractive option for "last-mile" commuting—bridging the gap between public transport and final destinations.

Tourists like them, too, as a convenient way to explore new cities.

Launched in Singapore in 2016, the global electric scooter market is valued at more than US$33.18 billion (A$49 billion) and is growing each year by around 10%.

More than 600 cities globally have embraced e-scooter sharing programs, yet reactions to these micro-mobility vehicles vary, making them a contentious urban planning issue.

Cities such as San Francisco and Madrid initially banned e-scooters, citing safety and public space concerns, but later introduced regulations for their use. Paris conducted a referendum, resulting in an e-scooter ban.

In Australia, the response has been more welcoming, though regulations differ across states and territories. What do we know about how safe e-scooters are? And what can we learn from other cities?

More e-scooters means more injuries

The growing popularity of e-scooters worldwide, including in Australian cities, has been mirrored by a significant rise in related injuries and hospital admissions.

Most of these incidents involve males in their late 20s or early 30s, commonly sustaining head, face and limb injuries. There is consistently low helmet use in those injured. Also, about 30% of people who go to hospital with e-scooter injuries have elevated blood alcohol levels. Crashes involving riders under the influence of alcohol are associated with more severe head and face injuries.

A study examining data from the Royal Melbourne Hospital reported 256 e-scooter-related injuries in the year to January 2023—including nine pedestrians—with a total hospitalization cost of A$1.9 million.

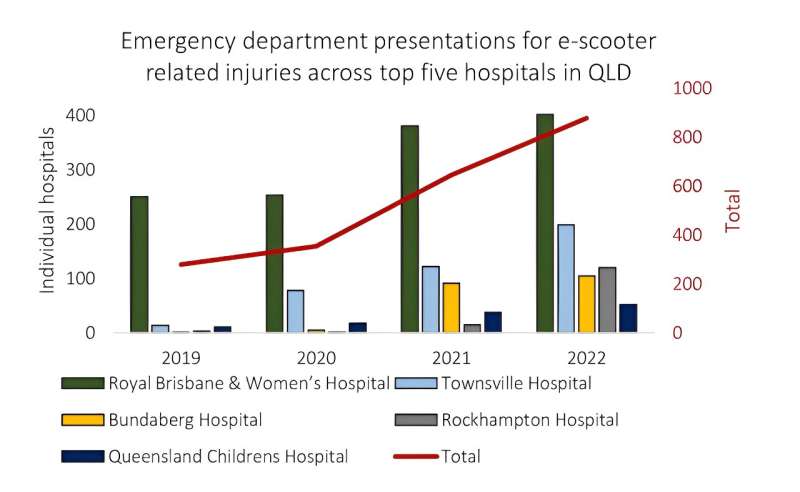

In Queensland, e-scooter-related presentations to hospitals rose from 279 in 2019 to 877 in 2022. By September of 2023, this figure had already reached 801 (full-year figures weren't available yet). Similar trends are seen in almost every city that has introduced e-scooters.

But are e-scooters riskier than other transport?

All modes of transport come with inherent safety risks. While trauma patient records in Western Australia show an almost 200% annual increase between 2017 and 2022 in e-scooter related admissions, these figures still remain well below those for cyclist injuries.

We need to understand the relative risk of e-scooters—a newcomer to the mobility market—and compare it to other established forms of transport. A proper assessment also considers exposure—the total number of trips and the distance covered.

A study in the United Kingdom, incorporating exposure factors using data from an e-scooter rideshare operator and hospital admissions combined, indicates that although hospital presentations increased during the e-scooter trial period, the injury rate was comparable to that of bicycles.

But it might be a different story when it comes to the severity of injuries. Some studies suggest a higher incidence of severe trauma among e-scooter users compared to cyclists. One study of more than 5,000 patients treated at a major trauma center in Paris found that, while the mortality rate from e-scooter crashes wasn't higher than that of bicycles or motorbikes, the risk of severe traumatic brain injuries was slightly higher than bicycles (26% compared to 22%).

There is evidence e-scooter riders tend to engage in significantly more risky behavior than cyclists. Compared to injured bicyclists, those injured while riding e-scooters:

- tend to be younger

- are more frequently found to be intoxicated

- exhibit a lower rate of helmet use

- and are more commonly involved in accidents at night or on weekends.

- Provided by The Conversation This article is republished from

- The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.