The construction of a mining access road near Cat Lake First Nation is now on hold.

A court judge has granted, at the request of the community, an interim order pausing the work by First Mining Gold.

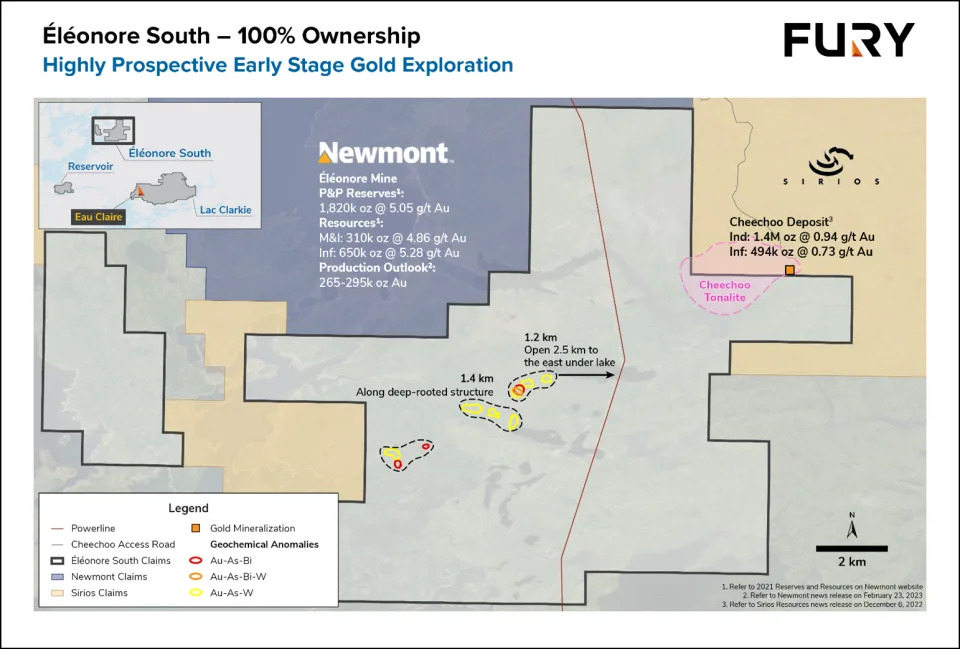

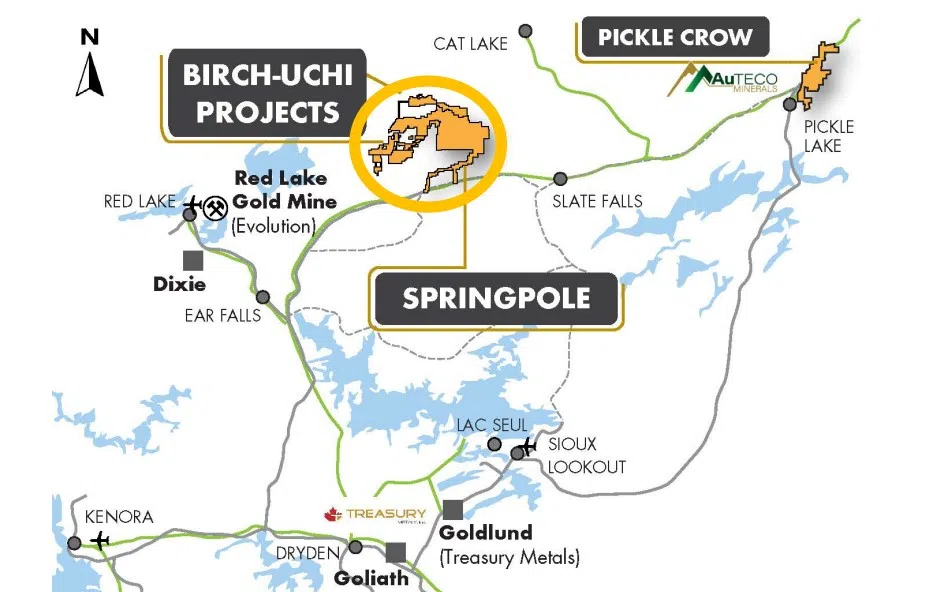

The company received permission from the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry to build an 18-kilometre road to its Springpole mining project.

The company wants the road to avoid travel over winter roads.

Since establishing a camp in 2015, First Mining has used an ice road to move supplies and access the site.

It travels 40 kilometres, of which 34 is over ice and half over nearby Birch Lake.

First Mining says there have been several incidents of vehicles breaking through.

Cat Lake objects to the work, saying the Ministry ignored the community’s moratorium on mining exploration and related road work within its traditional territory.

First Mining indicates it proactively engaged with the area’s Indigenous communities over the past year regarding the safety concerns of using the ice road in light of the warm conditions experienced.

Chief Executive Officer Dan Wilton says he is disappointed by the band’s decision but is open to further talks.

“First Mining continues to listen to the concerns of Indigenous communities and is always willing to meet with community leaders to discuss these and any other matters regarding our activities in their traditional territories,” says Wilton in a release.

First Mining adds it has committed significant resources toward consultation efforts with the area’s Indigenous communities and is committed to working with them to understand the potential impacts on their rights and the traditional land users around the exploration Camp.

Gold in the Cold: First Mining's Winter Road Project Faces Legal Challenge in Northwestern Ontario

Discover the ongoing battle between economic development and indigenous rights in northwestern Ontario, as the construction of a winter road to the Springpole Gold Project exploration camp sparks legal resistance from the Cat Lake First Nation.

BNN Correspondents

26 Feb 2024

/bnn/media/media_files/9874d1e57151f4ebd57adc1a829d2335bb8513be0e15efa34b873ce17dc50f18.jpg)

In the heart of northwestern Ontario, a battle unfolds that pits the promise of economic development against the preservation of indigenous rights and environmental integrity. On February 9, 2024, First Mining Gold Corp. received construction permits for a temporary winter road leading to the Springpole Gold Project exploration camp. This development, heralded by some as a step forward in the gold exploration sector, has been met with legal resistance from the Cat Lake First Nation, sparking a conversation that transcends the mere construction of an 18 km pathway through the wilderness.

The Road Not Taken Lightly

The proposed winter road is not just a matter of logistics but a narrative of safety, environmental stewardship, and community engagement. Designed to provide a safer alternative for transporting supplies and personnel, the road aims to mitigate the risks posed by increasingly unreliable ice roads—a consequence of warmer winter conditions. Since 2015, First Mining has operated the remote exploration camp with a commitment to minimizing environmental impact and respecting traditional land use practices. Yet, the road's construction has been paused by an interim stay, following the Cat Lake First Nation's notification of their intent to challenge the permits issued by the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry.

A Legal and Ethical Quagmire

The challenge put forth by the Cat Lake First Nation underscores a complex intersection of legal rights, environmental ethics, and indigenous sovereignty. While First Mining emphasizes its dedication to safety and environmental responsibility, the First Nation's concerns highlight the potential for disruption and the need for thorough consultation and consent processes. This scenario is emblematic of a broader dialogue in Canada and worldwide, where the rights and wishes of indigenous communities are increasingly recognized in the face of industrial expansion.

Looking Forward: Engagement and Resolution

Despite the current legal standoff, First Mining maintains its commitment to ongoing dialogue and engagement with the Cat Lake First Nation and other indigenous communities. The outcome of this situation could set a precedent for how resource exploration companies and indigenous territories can coexist and collaborate. As the legal process unfolds, both parties may find an opportunity to redefine the parameters of mutual respect, environmental stewardship, and economic development in a way that honors the land and its original caretakers.

In this unfolding story of gold, ice, and indigenous rights, the path forward is as much about building bridges of understanding and cooperation as it is about constructing a road through the wilderness. As the case progresses, it will undoubtedly continue to attract attention from those invested in the future of resource exploration, indigenous sovereignty, and environmental preservation in Canada and beyond.