The Rebirth of Bangladesh

The physical organisation of the Bengalee is feeble even to effeminacy. He lives in a constant vapour bath. His pursuits are sedentary, his limbs delicate, his movements languid. During many ages he has been trampled upon by men of bolder and more hardy breeds. Courage, independence, veracity, are qualities to which his constitution and his situation are equally unfavourable. His mind bears a singular analogy to his body. It is weak even to helplessness for purposes of manly resistance…

— Macaulay (1841)

Chhayanaut, the premier cultural institution of the country, employs what one scholar of fascism, Roger Griffin, has termed palingenesis, “a framing device to emphasise cultural and national renewal” (Zac Gershbergh and Sean Illing. The Paradox of Democracy: Free Speech, Open Media and Perilous Persuasion, (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2022), p 126). Gershberg and Illing cite D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, the modern medium of the cinema for a mass audience: the Lost Cause of a heroic South, reinvigorated by the Ku Klux Klan.

“Pakistan’s rulers, since its inception in 1947, tried to use religion to rupture the plural cultural identity of Muslim Bengalis; this was reflected in their onslaught on Bangla language and culture,” announces the Chhayanaut website. We will see below that this does not fact-check. “Chhayanaut created a landmark national tradition by launching the celebration of Bengali seasons. The musical welcome on the first dawn of Baisakh [the opening month of the Bengali year] under the banyan tree in Ramna, begun in 1967, brought back the Bengali new year into the consciousness of city dwellers. Thus, Chhayanaut has become a partner in the glory of the Bengali passage that began with a cultural renaissance and led to the war for independence. During the liberation war, Chhayanaut singers organised performances to inspire freedom fighters and refugees. After independence, Chhayanaut has been involved in seeking creative ways to broaden and intensify the practice of music and, more broadly, the celebration of Bangla culture…Chhayanaut believes the nation will find its path to development through this cultural renaissance (italics added).” In fact, the “Bengali calendar” issued from the court of the Mughal Emperor Akbar. “Celebrations of Pahela Baishakh started from Akbar’s reign (1556 – 1605).”

Needless to add, Bengali consciousness played no role in these celebrations. An imperial edict, for purposes of tax collection, constituted the new calendar: such top-down, supine payment of taxes prompted the expression for Asians as a whole: “born taxpayers”: “The nascent absolutist states of Europe had to struggle long and hard before they established fiscal absolutism; of the Asian populations it can fairly be said, in the light of their 2,000-year-old histories, that they were “born taxpayers” (S. E. Finer, The History of Government from the Earliest Times, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), p 1303)”.

According to a former student, Chhayanaut begins its Victory Day musical at precisely 3:45 pm – when the Pakistan army surrendered to the Indian army on December 16 1971. Apart from the singing and dancing, “Chhayanaut has a dress code for people who want to sit in the audience. The audience must wear something in green or red”, the colours of the flag — reminding one of the indoctrination scene in Stalag 17 (1953).

Whatever their goals, their one achievement stands out: subordinating the individual to the group. And this group, far from including all Bengalis actually excludes most: the illiterate, and their taste in music and dance. When the author questioned three exponents of Bengali culture, they were unanimous in condemning the movie item dances of Naila Nayem, a sex symbol in Bangladesh (pictured). “Indecency” must be ruled out, commented one of the trio. The puritanism of the Bengali middle class appears unclothed.

We are not surprised: the imperative of cohesion trumps all others. As history has shown, the boot-in-the-face is a Freudian need of the herd:

Since a group is in no doubt as to what constitutes truth or error, and is conscious, moreover, of its own great strength, it is as intolerant as it is obedient to authority. It respects force and can only be slightly influenced by kindness, which it regards merely as a form of weakness. What it demands of its heroes is strength, or even violence. It wants to be ruled and oppressed and to fear its masters. Fundamentally it is entirely conservative, and it has a deep aversion from all innovations and advances and an unbounded respect for tradition…

And so Chhayanaut believes “that if people come together in singing songs of loving the motherland and its people, those divisions will dissolve. Chhayanaut believes that Bangalees can be united once again through culture…Chhayanaut hopes that their new initiative to bring people together in the spirit of patriotism will be successful (italics supplied).”

Patriotism: the last refuge?

The Soft Power

Chhayanaut promotes the arts on behalf of the ruling party. Its founders earned their nationalist spurs by singing songs – discouraged by the Pakistan government before and during the second Indo-Pak war over Kashmir – by Rabindranath Tagore, the Indian Nobel laureate, on his hundredth birth anniversary, a lot like the Boston Symphony Orchestra not playing Beethoven on the eve of the Great War. By cocking a snook at the authorities of a country founded on Islamic unity, Chhayanaut’s defiance earned merit for heroic anti-Islamism.

Which brings us to Rabindranath Tagore and his songs.

The songs of Nobel-Prize-winning Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) — one of which constitutes the national anthem of Bangladesh — betrays the elitism of our nationalism. Demotic Bengali is sharply different from hieratic Bengali — the latter only spoken by the uber-elite, the self-consciously nationalist. Education is the national cosmetic, concealing all wrinkles of the particular. Rabindranath belongs among the educated.

Rabindranath Tagore symbolised anti-Islamism, Bengalism and pan-Bengalism, all of which makes him a prophet-like personality in the salons of Dhaka, Bangladesh. None of this would have been possible but for the Nobel Prize in literature. Sanjida Khatun observes that his protean output “has made Tagore songs an essential part of life of the Bengalis who sing them in happiness, in distress, and at work”. The mythology around Rabindranath’s songs suggests a less innocent explanation.

Ian Jack, writing on the god-man’s hundred-and-fiftieth birth anniversary, observes: “Then again, love of literature can slide into fetishism, and from there, obscenity. When Tagore died in 1941, the huge crowd around his funeral cortege plucked hairs from his head. At the cremation pyre, mourners burst through the cordon before the body had been completely consumed by fire, searching for bones and keepsakes.” That’s not love of literature; that’s love of divinity. And godmen tend to proliferate in the “mystical” Orient: recall the Beatles’ guru, Maharishi Maheshi Yogi, father of Transcendental Meditation (TM), in whose dishonour a disillusioned John Lennon composed Sexy Sadie. His genuflecting devotees must be reciting mantras to avert a similar fate for god-man Tagore (although a highly popular lampoon of one of the guru’s songs by Roddur Roy on YouTube manages to shock and amuse) .

Art has long been co-opted here for the purpose of propaganda. After the division of Bengal in 1905, the Hindu Bengali elite agitated for restored unity. One of these agitators was Rabindranath Tagore. He composed Banglar mati Banglar jal (“The soil of Bengal, the water of Bengal”). Dwijendralal wrote Banga amar janani amar (“Bengal is my land and my mother”); Atulprasad wrote Balo balo balo sabe (“Say, say, say everyone”). “Among others who contributed to the nationalistic movement was Mukundas, whose jatras [village plays], Desher Gan (patriotic song) and Matrpuja (Worship of the Mother), motivated the Bangalis to fight for their rights and against the despotic rule of the English.” These worked: As Percival Spear remarks, “It had been shown that the despised bourgeois might on occasion get a popular backing” (A History of India, Volume 2 (New Delhi: Penguin Books, 1990), p 177).

“Bande Mataram” (“Hail to Thee Mother”) became the Congress’s national anthem, its words taken from Anandamath, a popular – and “virulently anti-Muslim” – Bengali novel by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, and its music composed by Rabindranath Tagore (the observation on the nature of the novel comes from Ian Stephens, Pakistan: Old Country/New Nation (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1964), p 86).

Chaterjee’s slogans – bande mataram, matribhumi (motherland), janmabhumi (birth land), swaraj (self rule), mantra, and so on – were used by militant Hindu nationalists, mostly from Bengal, and many of these words continue to resonate powerfully in Bangladesh today. Moderate leaders of the Indian National Congress did not take immediately to Chaterjee’s Hindu nationalist slogans, but were won over by their appeal to the youth during the swadeshi movement. Fuller, the Lieutenant-Governor of East Bengal and Assam, forbade the chanting of bande mataram in public. Congress’s continued emphasis on aspects of militant Hindu nationalism – such as the replacement of Urdu by Hindi, and the singing of bande mataram in schools and on public occasions – was resented by Muslims (Hugh Tinker, South Asia: A Short History (London: Pall Mall Press, 1966), pp 195, 220).

“Mother-goddess-worshipping Bengali Hindus believed that partition was nothing less than the vivisection of their ‘mother province’, and mass protest rallies before and after Bengal’s division on October 16, 1905, attracted millions of people theretofore untouched by politics of any variety,” according to the Britannica. The swadeshi movement, as it was known, inspired terrorists who believed it a sacred duty to offer human sacrifices to the goddess Kali (Spear, p 176). What in actuality had been a purely administrative measure served to catapult national consciousness among the Hindu Bengalis. However, British officials made it clear that one consequence of the partition would be to give Muslims of Bengal a province where they would be dominant: it was a forerunner of Pakistan (Tinker, p 195). According to the Banglapedia article on the swadeshi movement, “The Swadeshi movement indirectly alienated the general Muslim public from national politics. They followed a separate course that culminated in the formation of the Muslim League (1906) in Dacca.” During the first meeting of the Muslim League, convened in Dacca in December 1906, the Agha Khan’s deputation issued a call “to protect and advance the political rights and interests of Mussalmans of India.” Other resolutions moved at the meeting expressed Muslim “loyalty to the British government,” support for the Bengal partition, and condemnation of the boycott movement.

Thus, an all-too-frequently heard Bengali song here goes: “The queen of all countries is my birth land (janmabhumi)”. The land figures prominently in the superabundance of deshattobodhok — patriotic — songs. “O the land of my country, my head touches you/You have commingled with my body….” Again: “You [martyrs] will be the beacon for the new swadesh….” While bhumi unequivocally means land, desh is more ambiguous: it can mean village or country. Since the transition from the former to the latter is far from complete, the word attempts to transfer emotions from the particular to the general, from the concrete to the abstract, mirroring inadequately the (far more successful) transition from pays to patrie, from Gesselschaft to Gemeinschaft (Finer, pp 143-4). The pejorative chasha (literally, farmer, but connotes the gauche, the uncultivated) tars all rural inhabitants (and even more in its stronger version, chasha-bhusha), and thereby the entire country, with the same brush. Patriotic songs may be seen as an heroic effort at restoration of self-esteem through imagined restoration of the physical unity of the two Bengals. The portability of song makes it a potent cultural artefact: emigres sing and hear these jingoistic songs in their new countries (typically America, Canada or Australia) where faux nationalism survives in the first generation, fortunately endowed with considerable human capital, the highly literate and numerate. The less fortunate are exhorted to love the motherland (matribhumi/janmabhumi) instead of voting with their feet. A single Youtube video, for instance, plays fifteen chauvinistic lays.

Mother, hail!…

Though seventy million voices through thy mouth sonorous shout,

Though twice seventy million hands hold trenchant sword-blades out,

Yet with all this power now,

Mother, wherefore powerless thou?

According to Bengali writer Nirad C. Chaudhury, “It was not the liberal political thought of the organisers of the Indian National Congress, but the Hindu revivalism of the last quarter of the nineteenth century — a movement which previously had been wholly confined to the field of religion — which was the driving force behind the anti-partition agitation of 1905 and subsequent years.” (Bande Mattaram lines, and Chaudhury, quoted, Tinker, pp 192-3). Rabindranath must be regarded as a pioneer of pan-Bengalism, and the successful reunion of Bengal as our Anschluss.

After Sheikh Hasina and her Awami League came to power in 1996, the state comfortably — and permanently — ensconced Chhayanaut headquarters in a tony part of town, “in recognition of it’s (sic) significant contributions for [the] last four decades to the Bangali cultural development”. “Virtually, the Chhayanaut operates unofficially as the apex body in the realm of music and dance.” The organisation, and others like it, provide psychic ammo for the government’s more muscular anti-Islamism – the soft power behind the hard power.

Death by a Thousand Mudras

The hard power went on display when, in 2021, Sheikh Hasina’s government invited Narendra Modi to the hundredth birth anniversary of her father Sheikh Mujib, the pater patriae and fifty years of national independence, announced by said pater on 26 March, 1971. The Islamist group, Hefazat–e-Islami, asked the government to cancel the invitation, thereby ‘showing respect to the sentiment of [the[ majority [of] people in Bangladesh”. In a written statement, they labeled Modi, not inaccurately, as ‘anti-Muslim and a butcher of Gujarat”. Members of the ruling party, and, predictably enough, its student wing, the Chatra League, attacked worshippers at the national mosque on 26 March after the Friday prayer to stymie the planned protest, leading to a nationwide fracas the next two days. At least fourteen Hefazat members were shot dead by police. “The Bangladeshi authorities must conduct prompt, thorough, impartial, and independent investigations into the death of at least 14 protesters across the country between 26 and 28 March,” insisted Amnesty International, “and respect the right to freedom of peaceful assembly, said 11 human rights organisations in a joint statement today. The organisations also called on the international community to urge Bangladeshi authorities to put an end to the practice of torturing and forcibly disappearing opposition activists.”

The Bangladesh Nrityashilpi Sangstha, “a welfare organisation of dance artistes” established in 1978, similarly serves up propaganda as dance. According to noted dance-teacher and impresario Laila Hassan: “It [Bangladesh Nrityashilpi Sangstha] believes that dance not only provides entertainment, it also speaks about the life, society, and culture of the country and its people, and that the liberation war and the country’s history and tradition can be presented through it”.

The Bulbul Lalitakala Academy serves a similar function: in addition to ministering to Terpsichore, the academy “plays a pivotal role in the cultural field through its regular observances of shaheed dibash [literally, “martyr’s day”, February 21, when young people were gunned down in a language protest in 1952] and independence day and celebrations of pahela baishakh and the spring festival….” On February 1 2024, a mega cultural event across the nation commemorated the shaheed dibash. The chief of the government-run cultural organisation, Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy mused: ‘We need culture-friendly political parties in the country in order to further the nation”. “Over 300 troupes are staging street plays at 21 venues in eight divisions at the festival,” announced the newspaper. “Twenty eight Dhaka-based troupes will stage plays at the Central Shaheed Minar till February 7.”

Gershberg and Illing note how the proto-fascist D’Aunzia, Commandante of Fiume and the first Il Duce, “established music as the state’s central purpose” (p 134). The authors quote Robert A. Paxton: fascism is “full of exciting political festival and clever publicity techniques” as well as “the propagandist manipulation of public opinion [to] replace debate about complicated issues” (p 136). Song-and-dance takes the place of tepid discussions of inflation and the current account deficit – although inflation eats away at the welfare of the poor. Hardly noticed, the Left Democratic Alliance, a group of left-leaning parties, held a protest rally on 20 March accusing the government of sponsoring “syndicates” that manipulate prices: “They said that the Awami League government had failed to control the price hike of essential commodities which increased sufferings of the common people of the country.” Not surprisingly, the only party to use the F-word is the socialist Jatiya Samajtantrk Dal (JSD) who observe “anti-fascism democracy day” on March 18 when several members were killed by the private army of Sheikh Mujb in 1974.

In the article “Dance Groups” of the Banglapedia, the writer observes, “Dance as an art form was seldom practised by Muslims before Gauhar Jamil set up a dance institution called Shilpakala Bhaban in 1948. After partition in 1947, despite the conservative tradition of the Bavgali (sic) society, a number of performers…contributed to removing old ways of thinking and entertainment.” The article on Bulbul Lalitakala Academy mentions “conservative Bengali Muslims”; and Chayyanaut “encountered many obstacles from [the] government of the time, because music and dance, especially of secular genre, were not much in consistence with the ideology of the Pakistani regime”. (Never mind that Ayub Khan removed Islam from the constitution (Ayesha Jalal, Democracy and Authoritarianism in South Asia, A Comparative and Historical Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), p 58) and passed the Muslim Family Law Ordinance, that the government set up the East Pakistan Film Development Corporation in 1957, that the Iranian singer Googoosh appeared regularly on TV in West Pakistan in the ‘60s, that the dance program Nritter Tale Tale aired every week, as the author recalls….) However, the article on “Classical Dance” observes: “…it appears that, like other classical dances, Kathak developed in the courtyards of Hindu temples and got a fresh lease of life under the patronage of the Mughal rulers”. The Britannnica concurs: Kathak, born of the marriage of Hindu and Muslim cultures, flourished in North India under Mughal influence.

“Classical Dance” also states: “During British rule, Indian classical dancing was patronised by the ruling classes, such as, rajas, maharajas, nawabs and zamindars as well as by British high officials who held ‘nautches’ in their private chambers.” And Bulbul Chowdhury, according to the same encyclopaedia, succeeded with dance precisely “by showing that dance was part of the Muslim-Mughal tradition”. Disinformation, or, not to put too fine a point on it, lying, conduces to incoherence. Another article in the Banglapedia observes that Khaleda Manzoor-e Khuda, a regular singer on Dacca Radio from 1951 to 1955, sang Tagore songs. “At that time as a Rabindra singer she was popularly known as Khaleda Fency Khanam.”

In an interview with the author, Benazir Salam, an expert in Indian classical dance with an MA from Rabindra Bharati, Kolkata and a teacher of dance at Dhaka University, observed of Kathak that it developed under Muslim rule, and, precisely for that reason, Chhayanaut allows its performance only at festivals, and relegates it to the tail-end.

The Men of Words, the Women of Song

We would do well to tarry a while and take note of Erich Hoffer on the subject, which will recur: “It is the deep-seated craving of the man of words for an exalted status which makes him oversensitive to any humiliation imposed on the class or community (racial, lingual or religious) to which he belongs however loosely. It was Napoleon’s humiliation of the Germans, particularly the Prussians, which drove Fichte and the German intellectuals to call on the German masses to unite into a mighty nation which would dominate Europe (The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements (New York: Perennial Classics, 2002), p 138)”. Hoffer uses the expression “the unwanted self” (p12). Macaulay’s attitude seems to have penetrated generations of this Delta, so much so that in Sheikh Mujb’s battle cry Joy Bangla [Long live Bengal/Bengali language] they feel wanted again.

Hoffer explains the intelligentsia’s solid support for the despotic dynasty of Bangladesh: During the upheavals of 2018, when student thugs of the ruling party beat up harmless child protesters demanding safer roads, Mehdi Hasan went head to head with a former Harvard professor, Gawhar Rizvi, who shamelessly defended every criminality perpetrated by the government; this author has spoken with men (and women) of words, and found the same resistance to criticism. When a bridge opened recently, the men and women of words and song galvanised themselves to create musical paeans to the dynasty (click here for the album Bangladesh: Despotic Dynasty, pictures taken by the author of the images of the ruling family plastered throughout the capital, a superb example of persuasive advertising designed to perpetuate our founding myth of the Father of the Nation). Intellectuals, “ a herd of independent minds”, in Chomsky’s words, appease our collective self-loathing by glorifying and exonerating thuggery.

In all fairness, it must be conceded that Bangladeshis are not uniquely prone to assuaging collective self-loathing through megaprojects: According to development economists Hla Myint and Anne O. Krueger, less developed countries’ resentment of developed economies stem, not only from measurable differences in income, but from less rational factors such as a reaction against the colonial past and their complex drives to achieve parity. “Thus, it is not uncommon to find their governments using a considerable proportion of their resources in prestige projects, ranging from steel mills, hydroelectric dams, universities, and defence expenditure to international athletics. These symbols of modernization may contribute a nationally shared satisfaction and pride but may or may not contribute to an increase in the measurable national income.” A picture of the Aswan Dam accompanies their article.

Peace is War

In 1928, Arthur Ponsonby, a British Member of Parliament, published his tell-all book on British propaganda which he called Falsehood in War-time: Containing An Assortment Of Lies Circulated Throughout The Nations During The Great War. In time of war, he observes with acerbity, “the stimulus of indignation, horror, and hatred must be assiduously and continuously pumped into the public mind by means of ‘propaganda’.

“A good deal depends on the quality of the lie. You must have intellectual lies for intellectual people and crude lies for popular consumption….

“Perhaps nothing did more to impress the public mind – and this is true in all countries – than the assistance given in propaganda by intellectuals and literary notables.” In short, the men of words.

The items italicised by the present author could be supplemented with and at all times. In Bangladesh today, the intelligentsia provides the context for a mindset suitable to a wartime situation: Fifty-two years after the third Indo-Pak war, seventy-two after Ekushey February Pakistan is still the enemy, and Islamists are fair game. George Orwell appreciated well the need for a state of permanent hostility against a fictive enemy to keep the citizenry loyal to the Party – a world dominated by three perpetually warring totalitarian police states. Emmanuel Goldstein, however, stars in the daily Two-Minute Hate – the equivalent of the propaganda by scribes, terpsichores and thespians in our country against the minuscule mullahs.

“He [Goldstein] was an object of hatred more constant than either Eurasia or Eastasia, since when Oceania was at war with one of these Powers it was generally at peace with the other. But what was strange was that although Goldstein was hated and despised by everybody, although every day and a thousand times a day, on platforms, on the telescreen, in newspapers, in books, his theories were refuted, smashed, ridiculed, held up to the general gaze for the pitiful rubbish that they were—in spite of all this, his influence never seemed to grow less.” How like the Islamsts of Bangladesh he sounds.

As Gershberg and Illing observe: “Fascism also promulgates the myth of sinister internal enemies that are simultaneously weak and devious (p 126)”.

“Nothing to report,” the lieutenant said with contempt.

“The Governor was at me again today,” the chief complained.

“Liquor?”

“No, a priest.”

“The last was shot weeks ago.”

“He doesn’t think so.”

“In the world of Graham Greene’s 1940 novel, The Power and the Glory,” muses a reviewer, “it’s a bad time to be a Catholic.” In the 2020s Bangladesh, it’s a bad time to be an Islamist, or even quasi-Islamist. (The quoted lines are from Vintage Books, London, 2002, p 32).

In 2017, Hafez (an Islamic scholar, not his real name) was, along with other religious students at Dhaka University dorms, beaten within an inch of their lives for being alleged Islamists. This routine torture of perceived “traitors” finally resulted two years later in the murder of Abrar Fahad, a straight-A student at the elite Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET) by his classmates who beat him for hours for his Facebook post criticising the prime minister: automatically, this made him an enemy, an Islamist (the BBC report leaves something to be desired: the murderous students belonged to the student wing of the ruling Awami League, the Bangladesh Chatra League (BCL), not the youth wing as reported; this is significant.). The second event caused a firestorm, the first, that of Hafez, went ignored: it’s open season on Islamists.

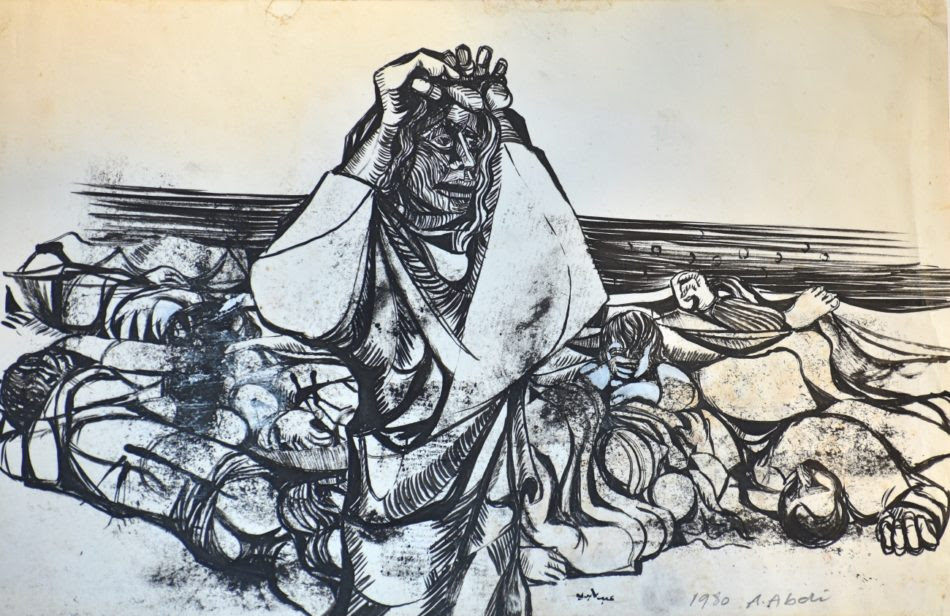

A highly abridged interview of Hafez conducted by this author several weeks ago appears below (this sort of news, being par for the course, hardly travels; hence, the delay in interviewing Hafez. Indeed, had Abrar Fahad not been an engineering student of elite stock, his murder, like that of the tailor, Biswajit Das (pictured), though highly publicised on TV channels and newspapers in his blood-stained shirt, vainly warding blows from the ruling party student thugs, might as well have been invisible. For the author’s observations on this selective attention, please click on What George Floyd’s Death Means – Or Should Mean – In Bangladesh ).

2017 August 13 11:30 pm

Interrogations begin – he’s forced to talk. It’s all pre-planned: the hall president and sidekicks are present

“Got him, Bhai [brother].”

Hafeez kneeled, salaamed.

The president is on the bed. The president’s room is on the 2nd floor; Hafez’s on the 5th floor

“Do you do Shibir [Islamist student wing of the main Islamist party]?”

Hafez is astounded. “No, Bhaiya [brother], I don’t.”

(Louder) “Do you do Shibir? Why do you do Shibir?”

“Bhaiya, I don’t.”

Slapping begins.

A friend who was an Islamic scholar, and similarly attired, is later brought in.

Heavier beating, kicking, ensue. A wooden stick is produced: they start hitting him on the back. Rods and water pipes are brought out from inside the president’s room. The hall secretary hits him on the thigh, right above the knee with pipes. The slaps are mostly on the eyes, ears and front face.

“Confess; we can burst your nose. Hey, who’s good at bursting noses?”

Bestiality of the above variety stems from nationalism, as documented by John Keane: “At the heart of nationalism – and among the most peculiar feature of its ‘grammar’ – is its simultaneous treatment of the Other as everything and nothing. The Other is seen as the knife at the throat of the nation. Nationalists are panicky and driven by friend-foe calculations; they suffer from a judgement disorder that convinces them that the Other nation lives at its own expense (Civil Society, (London: Polity Press, 1998), p. 96).” “…sinister internal enemies that are simultaneously weak and devious,” according to Gershberg and Illing.

A characteristic of collectivist organisations involves the use of children, such as the Chatra League of the ruling party. Interest in the child, and youth in general, arose in the early twentieth century, with such innocent bodies as the Boy Scouts. But it was followed by the “much more sinister and deliberately exploitative youth organisations of the totalitarian states of the 1920s and 1930s”, according to J.M. Roberts (Twentieth Century: A History of the World, 1901 to the Present (London: Penguin, 1999, p 642). “Young Pioneers in the USSR, the Hitler Youth in Germany, the balilla, Picolli Italiani and Figli della Lupa in Italy.” These countries vigorously excluded the Boy Scouts. The post-war youth market and culture never emerged in the east, where Mao’s Red Guards wreaked havoc in the 1960s. “Young Stalinists worshipped Stalin as an individual,” observes Richard Vinen. “Teenagers swelled the ranks of the party’s youth organisations….” They formed the most committed warriors against imperialism. “Astonishing as it seems in retrospect, the period when communist rule in Eastern Europe was at its most brutal was also the period during which many intelligent and well-meaning individuals thought it was a good thing” (A History in Fragments: Europe in the Twentieth Century (Da Capo Press, 2001), p 339, 344). Astonishing, indeed, except to someone domiciled in Bangladesh today. And Chhayanaut works its spell on children.

A Disappearing Act

When all eyes — those of the young and the old — are focussed on events several decades ago, thanks to Chhayanaut and the men of words, contemporary evils, as noted by Robert Paxton, such as the hounding of the Chief Justice, or the burning alive of innocent bystanders, enforced disappearances, state thuggery, extrajudicial killings, rapes by student politicians, appear remote and ephemeral. The stimulus of indignation, horror, and hatred is assiduously and continuously pumped into the public mind by means of “propaganda” — by the government and its handmaidens, the intelligentsia, “the men of words”, “the women of song and dance”.

Dhaka University, the quondam Oxford of the East, where alleged Islamists, as we have seen, receive considerable corporal suffering, earns the infamy of “concentration camp” , from the victims of its illustrious sons, mindful, no doubt, of the spirit of learning, albeit delivered, not in lectures, but in more tactile form. “It (Chhayanaut) believes that our celebration of fraternity and creativity under the broad rubric of an inclusive humanist culture will triumph, leaving behind religious bigotry, fundamentalism and xenophobia.” Read: getting rid of the Islamists, “simultaneously devious and weak”, by whatever means available to the state.

“Against this, there are other competing conceptions of art that are never fully suppressed, such as the archaic view that places art in the same general sphere of activity as ritual (a view with which I acknowledge considerable sympathy), and the conception of art as a vehicle of moral uplift or social progress, as is common in totalitarian societies where the creation of art becomes co-opted for the purpose of propaganda (for which, by contrast, I avow a proportional antipathy).” Most of us would go along with Justin E. H. Smith in his aptly-titled book Irrationality: A History of the Dark Side of Reason, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017), pp 22-23); we share his conceptions of art, and our sympathies lie with him. The Russian love story, “Boy meets tractor”, finds a creepy analogy: “Men and women meet bridge”.

The conception of Muslim civilisation as hopelessly philistine, if not proto-Khomeinist, persists in Bangladesh (as elsewhere). The following from Ronald Segal’s Islam’s Black Slaves: The Other Black Diaspora would come as a shock to teenagers and adults alike: “Female slaves were required in considerable numbers, for a variety of purposes. Some were musicians, singers and dancers – neither the status nor the style of a great house could do without a sitara, or chamber-orchestra – reciters and even composers of poetry. There were celebrated schools in Baghdad, Cordoba, and Medina that supplied tuition and training in both musical and literary skills. Such slaves were highly prized and costly (London: Atlantic Books, 2002, p 38).”

Show Me the Money

The above description of our cultural hanky panky may not appear more than children on a playful rampage, or inmates running the asylum (not counting the dead and disappeared for now). But the twang of the sitar and the thump of the tabla conceal the tinkle of coins and the thud of dosh. Gunnar Myrdal observed of South Asia in The Challenge of World Poverty: A World Anti-Poverty Programme in Outline: “…changes of government, or even of form of government, occur high over the heads of the masses of people and mainly imply merely a shift of the groups of persons in the upper strata who monopolise power (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971), p 212).” The transition from East Pakistan to Bangladesh, from military rule to democracy, occasioned changes of personnel at the top.

Albert Reynolds’ figures tell a disquieting story: “For countries at the early stages of development, primary education has the lowest unit costs and highest rates of economic return….Most South Asian governments (backed by self-interested elites) invested disproportionately in higher education: India had one of the highest growth rates in Asia for university students and the lowest for primary enrollments. In the 1970s, Bangladesh and Pakistan were increasing spending on higher education at the expense of primary schools, whose share in Bangladesh fell from 60 percent in 1973 to 44 percent in 1981 (One World Divisible: A Global History Since 1945 (New York: W.W.Norton and Co., 2000), p 302, 307, emphases added).” We see these statistics clearly bearing out Myrdal’s observation regarding elite-churning.

For what prevails in the political economy of Bangladesh is an oligarchy in cahoots with the ruling party; the Center for Policy Dialogue, a think tank, went on record as saying: “The current practice of recruiting Board of Directors [to state-owned commercial banks, or SCBs] on political grounds has to be discontinued. Studies have shown that financial reporting fraud in banks is more likely if the Board of Directors is dominated by insiders”. The level of non-performing loans (NPLs) has increased steadily since 2008, when the current government returned to power: between 2008 and 2018, the level of dud loans soared 297%. Syed Yusuf Saadat, research associate of the think-tank, observed, “In 2017, a single business group gained control of more than seven private banks.” The IMF observed that “important and connected borrowers default because they can”.

The case study of Islami Bank provides a detailed picture, not only of the government’s anti-Islamism, but also the paw-in-the-public-till syndrome that promotes loyalty to the dynasty. “Established in 1983 as Bangladesh’s first bank run on Islamic principles, Islami thrived by handling a large share of remittances from emigrant workers and by lending to the booming garment industry. Its troubles stem from its links with Jamaat-e-Islami, Bangladesh’s largest Islamist party, which allied with Pakistan during the war of succession of 1971.” One of the first acts by the prime minister, Sheikh Hasina, on coming to power in 2009 was to try “war criminals” in kangaroo courts. “Leading figures from the Jamaat were sentenced to imprisonment or hanging.” Then came the asset-seizure. In 2017, the prime minister sent government intelligence operatives to oust senior executives and put in place her cronies: a boardroom coup. The cronies swiftly turned a healthy bank sick.

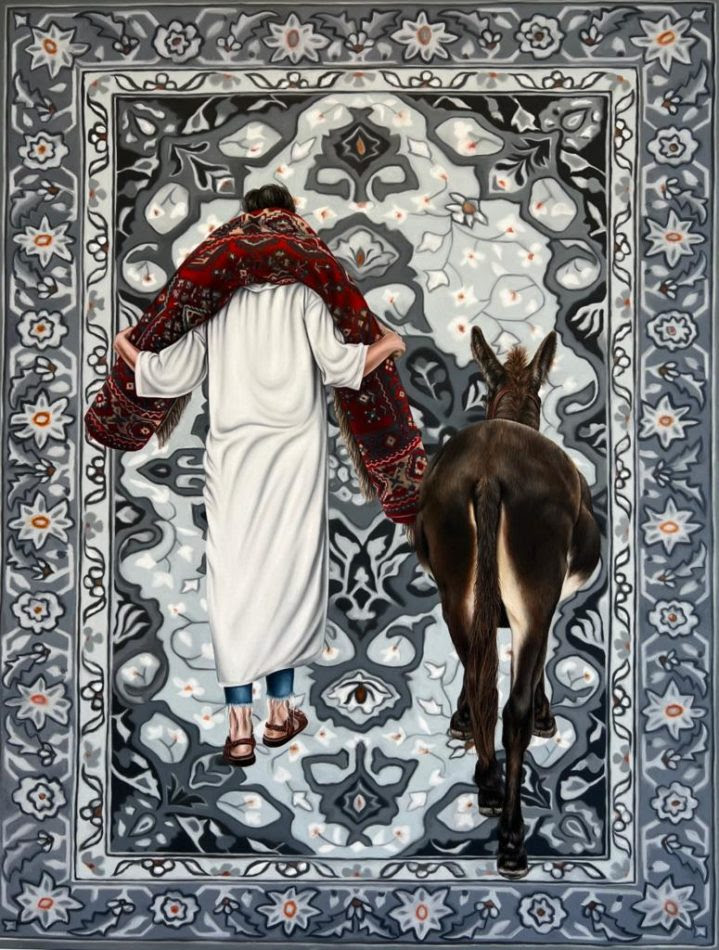

While Chhayanaut greets the new Bengali year under a banyan, and grandmothers in the vernacular, its members and devotees don colour-coded sarees (white with a red border for Baisakh, yellow for Falgun, blue for Ashar, red and green for Victory Day), hog watered rice rural-style, sing Tagore in soirees…the wonga wends its way….

As Don Fabrizio’s nephew observes in Giuseppe Di Lampedusa’s The Leopard, “If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change. D’you understand (trans. Archibald Colquhoun, (New York:Random House, 1960), p 40)?”

UPDATE: 30 March: “red and gold for Victory Day” was amended to “red and green for Victory Day.”

Iftekhar Sayeed was born and lives in Dhaka, Bangladesh. He teaches English and is a freelance journalist who has contributed to several media outlets. Read other articles by Iftekhar, or visit Iftekhar's website.