Proud Seafarers Have Strong Doubts About the Safety of Autonomy

A survey of Norwegian bridge officers found considerable skepticism about the safety benefits of autonomy

[By Sølvi Normannsen]

Despite their great trust in on-board autopilots, bridge officers do not believe that autonomous ships will make shipping safer. Moreover, the greater the professional commitment and pride of the bridge officers, the less confidence they have in automation increasing safety at sea.

The maritime profession is among the world’s oldest professions, and today’s shipping is based on long and proud traditions. Professional pride and commitment are often deeply ingrained in seafarers, and for many, the job is more of a way of life. New technologies will bring about major changes in the work of bridge officers, who have the ultimate responsibility on board Norwegian vessels.

Strong doubts about safety

“Bridge officers rely on automated systems that are already found on board, such as advanced autopilot systems. However, there is strong skepticism, almost mistrust, that increased automation and autonomous (meaning self-driving) ships will contribute positively to safety,” says Asbjørn Lein Aalberg, a PhD candidate at NTNU’s Department of Industrial Economics and Technology Management and SINTEF Digital.

Aalberg has studied the relationship between maritime officers’ professional commitment and the attitudes they have towards automation and autonomous ships as part of his PhD research. The study ‘Pride and mistrust? The association between maritime bridge crew officers’ professional commitment and trust in autonomy’ was recently published in the WMU Journal of Maritime Affairs. The research was conducted in collaboration with the Norwegian Maritime Authority and Safetec.

More than 8,000 Norwegian bridge officers participated in the 2023 survey (in Norwegian). This is probably the largest survey in this field to date, both nationally and internationally.

Looking for the reasons behind the skepticism

Sooner or later, society must accept using modes of transport such as passenger ferries that have little or no crew on board. Aalberg believes that in order for operations to be as safe as possible, employees are needed who know how to control and monitor this automation.

“If we are to get there, it is important to understand what is behind the seafarers’ skepticism. We need their engagement, willingness and interest to ensure that the technology and systems being developed are fit for purpose,” says the researcher.

The reason why bridge officers trust autopilots and similar systems is that they themselves are still in control and can choose to turn the systems on and off as and when they see fit.

Few women in the sample

Aalberg has taken a closer look at the answers given by captains and navigators on board. Collectively, this group consists of 1789 Norwegian and 227 international bridge officers of all ages, with everything from 0 to more than 26 years of experience. Women constitute only 11 percent of Norwegian seafarers, and only 2.4 per cent of the participants in this survey.

“This probably reflects the fact that there are even fewer women among the people working on the ship’s bridge,” says Aalberg.

Among other things, the bridge officers were asked about:

- Their thoughts and feelings about the automation of work tasks

- Their confidence in autonomous technology

- Their professional commitment and pride

- Their own management work related to safety

Seafarers with an extreme sense of duty

Aalberg says that bridge officers are very proud of their work and exhibit what he would call a rather extreme sense of duty to their own profession.

“This pride may lead to additional mistrust when faced with radical changes. In fact, we found that those who take the greatest pride in their profession are most sceptical about technological developments,” says the researcher.

Another finding that he finds quite alarming is this: among the bridge officers who take the greatest pride in their profession, it is the younger ones who have the least faith in autonomy.

“When envisioning their future career, maybe they feel like they have more to lose,” says Aalberg.

One of the oldest professions in the world

This area has seen little research, and Aalberg says we don’t currently know enough about why seafarers exhibit such strong mistrust. One reason for this is that there are currently not many autonomous ships, and they are a hot topic of speculation and debate. It is therefore important to emphasize that different points of view may be based on rumors, vague impressions and unfounded notions of what the changes will entail.

It is also often the case that autonomous vessels are spoken positively about by individuals who are relative newcomers to the maritime industry. The survey indicates that this could spark uncertainty among seafarers, both in terms of the motives and intentions behind autonomy.

“Despite the fact that there seems to be a great need for seafarers in the future, some people may be afraid of losing their jobs. But I think the skepticism is more about the changes being made to the nature of their work. For example, there would be a great deal of uncertainty among captains if the position were to lose its independence. We must not forget that the maritime profession has a very long tradition, where a captain’s authority and control have always been strong,” Aalberg says.

Researcher Asbjørn Lein Aalberg hopes authorities can use the research results in dialogue with shipping companies and technology providers. He says that these different groups should include seafarers when developing new concepts and technological solutions. Photo: SFI MOVE

Professional discretion

The PhD candidate has also interviewed 31 Norwegian seafarers on board highly automated Norwegian passenger ferries about their confidence in the advanced automated systems that have been installed. This study gives some hints about what it takes for bridge officers to trust advanced technology. Among other things, it relates to their lack of trust in the machines’ ability to demonstrate true ‘seamanship’ and exercise professional discretion in traffic. In addition, the interviewees did not believe that the machines will manage emergency situations well enough. All in all, they believe that people are best suited to making decisions in complicated situations.

“The reason they still trust autopilots and similar systems is that they themselves have control and the option to turn them on or off as and when they see fit,” Aalberg says.

The shipping company and technology developers have also had a very long and ultimately successful development process that he believes is needed to satisfy proud seafarers.

However, all the informants were skeptical about the impending changes and expressed concern that increased automation would compromise safety at sea.

Autopilot is ok, autonomy is not

The studies show that bridge officers make a clear distinction between automation and autonomy. Automation involves machines taking over some of their tasks, while autonomy, taken to its ultimate conclusion, means unmanned ships.

Aalberg provides a nuanced perspective on the development.

“Many researchers argue that humans will play a crucial role in human-automation collaboration, even on autonomous ships. Previously, there was more talk about removing people altogether, to put it bluntly,” says the researcher.

Seafarers must be consulted

He hopes the authorities can use the results of the research in dialogue with shipping companies and technology providers. He says they should include seafarers when developing new concepts and technological solutions.

“They have to make, and talk about, innovations in such a way that it sparks interest instead of skepticism,” he says.

He also believes that projects involving technological development should openly share real results from testing in order to provide a nuanced perspective of what seafarers may see as as being overly idealized.

“We also know that seafarers gain trust in advanced technology by trying the technology themselves. Keynote speakers or even colleagues talking about the systems is simply not enough. They want to try them themselves and see if the automation makes the same choices that they would have made, so perhaps the development process should be structured accordingly,” Aalberg says.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.

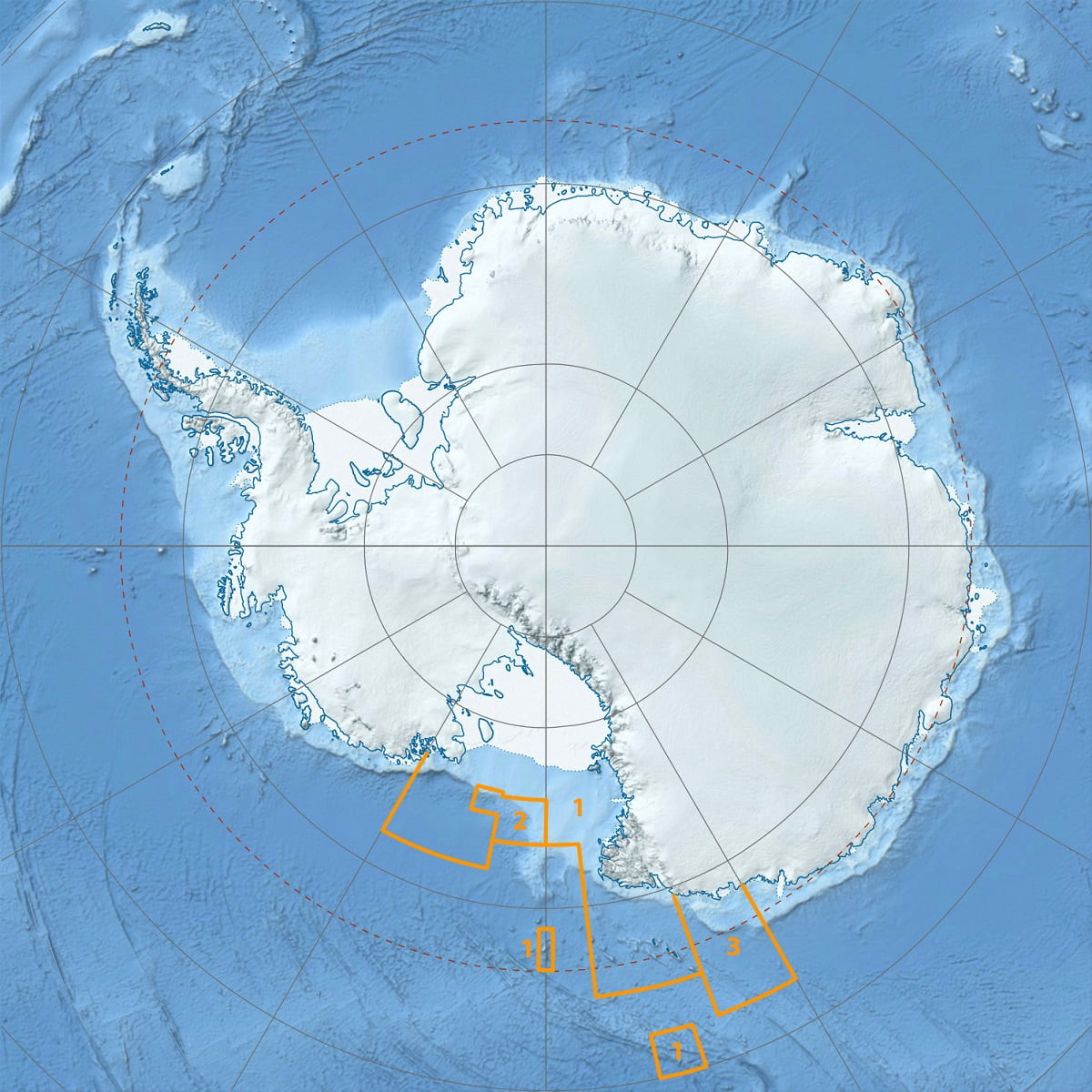

The Ross Sea Marine Protected Area includes a (1) General Protection Zone; (2) Special Research Zone; and (3) Krill Research Zone (Wikimedia Commons)

The Ross Sea Marine Protected Area includes a (1) General Protection Zone; (2) Special Research Zone; and (3) Krill Research Zone (Wikimedia Commons)