Aboriginal people made pottery, sailed to distant islands thousands of years before Europeans arrived

Pottery was largely unknown in Australia before the recent past, despite well-known pottery traditions in nearby Papua New Guinea and the islands of the western Pacific. The absence of ancient Indigenous pottery in Australia has long puzzled researchers.

Over the past 400 years, pottery from southeast Asia appeared across northern Australia, associated with the activities of Makassan people from Sulawesi (this activity was mainly trepanging, or collecting sea cucumbers). Older pottery in Australia is only known from the Torres Strait adjacent to the Papua New Guinea coast, where a few dozen pottery fragments have been reported, mostly dating to around 1700 years ago.

Why has no evidence been found of early pottery use by Aboriginal people? Various explanations have been proposed, including suggesting that archaeologists simply weren't looking hard enough. Well now, we've found some.

In new research published in Quaternary Science Reviews, we report the oldest securely dated ceramics found in Australia from archaeological excavations on Jiigurru (in the Lizard Island group) on the northern Great Barrier Reef located 600km south of Torres Strait. Our analysis shows the pottery was made locally more than 1,800 years ago.

Finding pottery at Jiigurru

Back in 2006, several pieces of pottery were found in Blue Lagoon on Jiigurru, 33km off mainland Cape York Peninsula.

Finding pottery at Jiigurru raised some big questions. How old was it? Was it made by local Aboriginal communities? Or was it traded in from elsewhere? If so, where did it come from? Was it from a European shipwreck? Or was it made by the famous Lapita people who colonized the islands of the southwest Pacific?

Our team excavated several more pieces of pottery from Blue Lagoon in 2009, 2010 and 2012.

Preliminary analyses showed most of the pottery was made from local materials. However, despite a lot of work, our efforts to determine the age of this pottery were inconclusive and we were no closer to working out how old it is, or who made it.

In 2013 we went back to Jiigurru to excavate a shell midden on a headland near where the Blue Lagoon pottery was found. A shell midden represents a place where people lived, containing food remains (shells, bones), charcoal from campfires, and stone tools left behind.

Radiocarbon dating showed people started camping at this place some 4,000 years ago, making it the oldest site then known at Jiigurru. But no pottery was found.

A broader search

By 2016 the team had reached a dead end in investigating the few pieces of pottery we had. Instead, working in partnership with Traditional Owners, we turned the research program to the extraordinary Indigenous history of the whole of Jiigurru and began surveying all the islands.

In 2017 we began excavating a large shell midden at Jiigurru located during the surveys.

To our amazement, around 40cm below the surface we began to find pieces of pottery among the shells in the excavation. We knew this was a big deal. We carefully bagged each piece of pottery and mapped where each sherd came from, and kept digging.

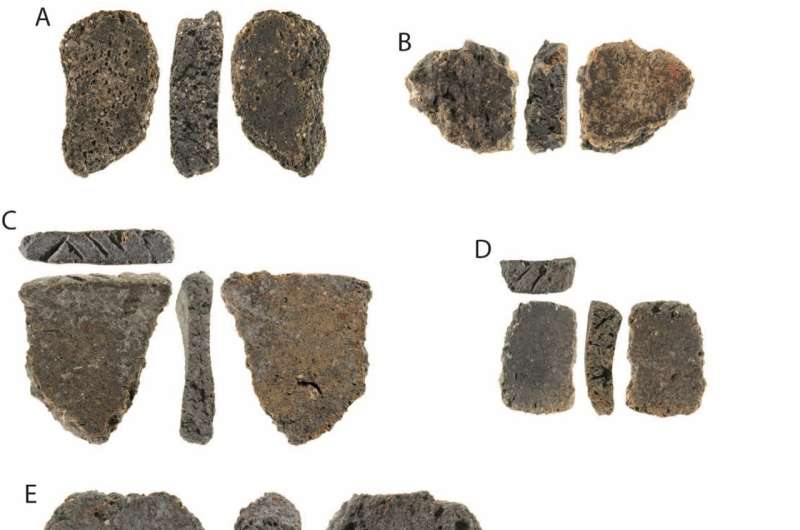

The pottery stopped at about 80cm depth, with 82 pieces of pottery in total. Most are very small, with an average length of just 18 millimeters. The pottery assemblage includes rim and neck pieces and some of the pottery is decorated with pigment and incised lines.

The oldest pottery

But we had another surprise waiting for us.

The deepest cultural material was found nearly two meters below the surface, in levels we radiocarbon dated to around 6,500 years ago. This is the earliest evidence for offshore island use on the northern Great Barrier Reef.

The reef shells eaten and discarded in these lowest levels had been buried so quickly that they still have color on their surfaces. Archaeological sites of this depth and age are uncommon anywhere around the Australian coast.

Radiocarbon dating of charcoal and shells found close to the pottery shows that it is between 2,950 and 1,815 years old, making it the earliest securely dated pottery ever found in Australia. Analysis of the clays and tempers shows that all of the pottery was likely made on Jiigurru.

What does it tell us that we didn't already know?

The findings are clear evidence that Aboriginal people made and used pottery thousands of years ago.

The archaeological evidence does not point to outsiders bringing pottery directly to Jiigurru. Instead, the evidence shows that Cape York First Nations communities were intimately engaged in ancient maritime networks, connecting them with peoples, knowledges and technologies across the Coral Sea region, including the knowledge of how to make pottery.

They were not isolated or geographically constrained, as once conceived.

The results also demonstrate that Aboriginal communities had sophisticated watercraft and navigational skills in using their Sea Country estates more than 6,000 years ago.

What else don't we know?

The Jiigurru pottery gives us new insight into Australia's history and the international reach of First Nations communities thousands of years before British invasion in 1788.

Very little research has been conducted anywhere on eastern Cape York Peninsula. We think it is very unlikely that Jiigurru holds the only secrets to our country's peopled past. What other cultural and historical surprises await to be found?

More information: Sean Ulm et al, Early Aboriginal pottery production and offshore island occupation on Jiigurru (Lizard Island group), Great Barrier Reef, Australia, Quaternary Science Reviews (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2024.108624

Journal information: Quaternary Science Reviews

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()