AMLO NEO-LIBERAL

AMLO Expanded Mexico’s Military. It Built Airports Instead of Reining In Murders

Andrea Navarro

Fri, April 19, 2024

In his six years as Mexico’s president, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador gave his country’s military two important jobs: build infrastructure works to supercharge the economy and rein in violent crime.

By the end of his presidency, he will have accomplished only one — and left the other worse than ever.

AMLO, as the president is known, has used Mexico’s armed forces to build airports, construct a nearly 1,000-mile long railroad through the Mayan jungle, and create a state-owned airline. Those initiatives are likely to burnish his economic legacy as he prepares to leave office following this June’s presidential election.

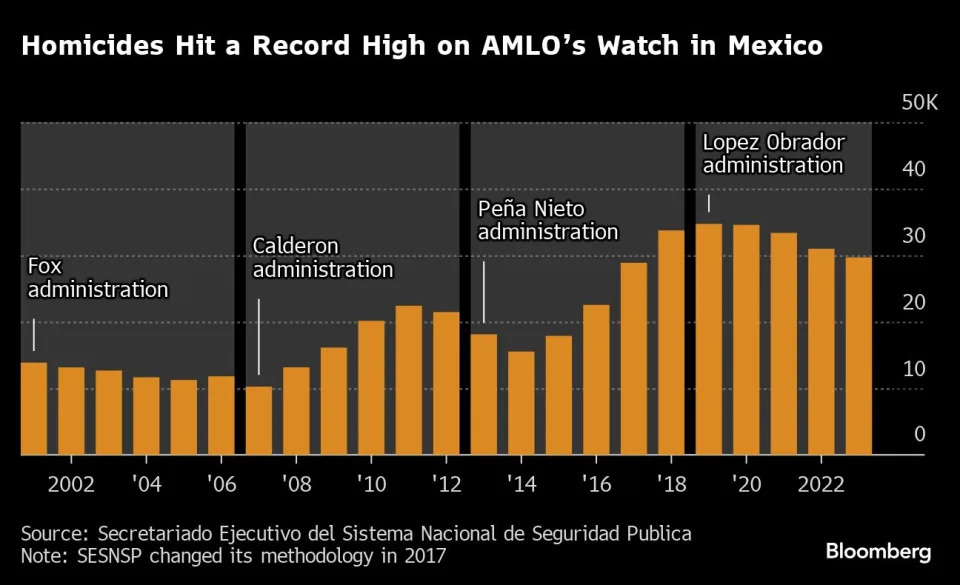

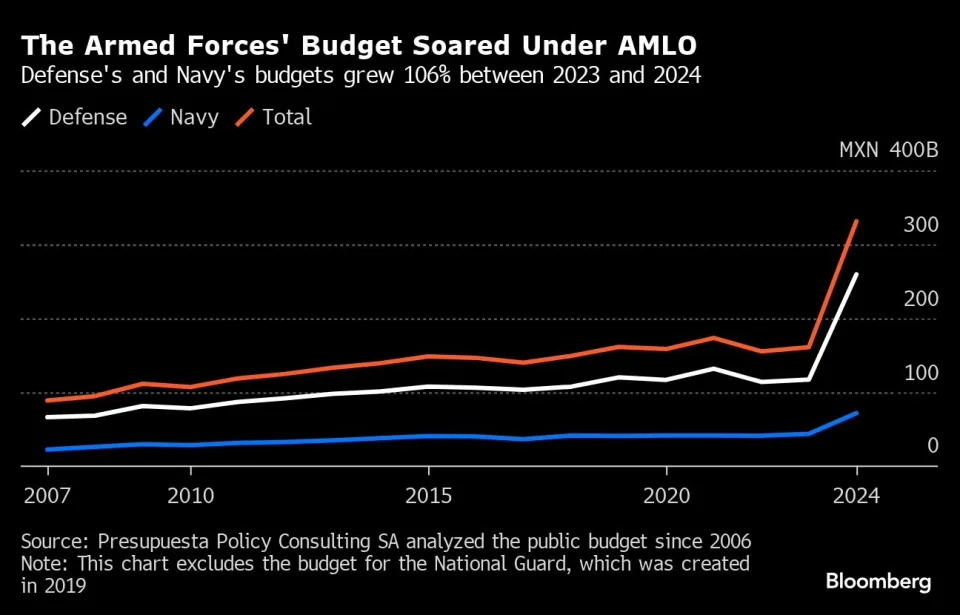

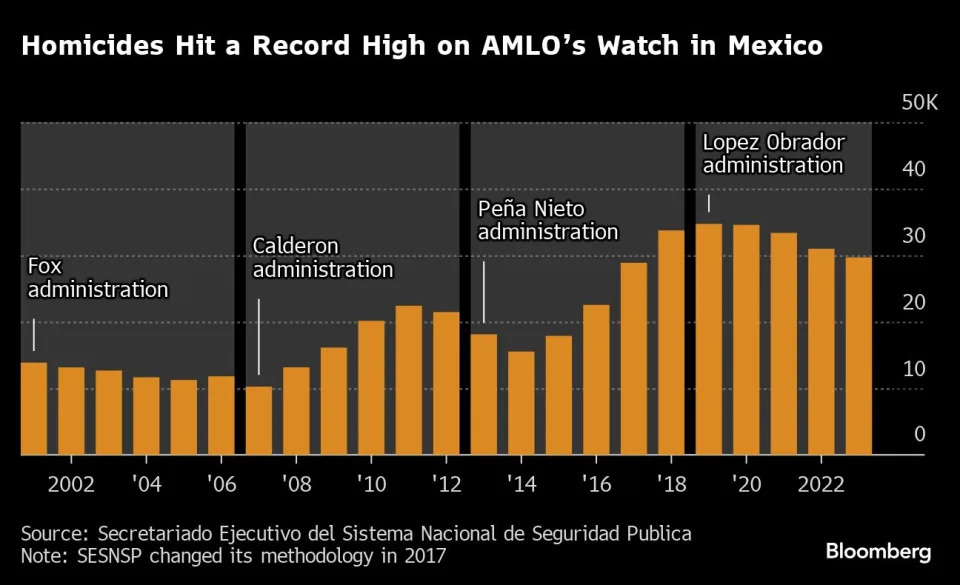

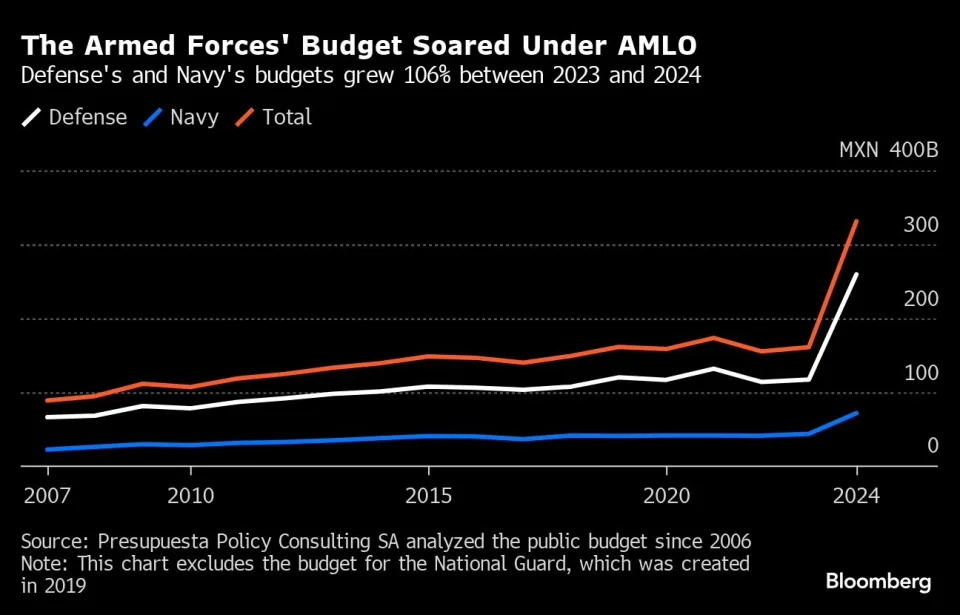

Yet Lopez Obrador will leave another legacy as well. His administration has presided over the bloodiest term in the nation’s recent history, with more than 170,000 homicides since he took office in 2018 through February. That is a 26% increase from the 135,345 murders during the term of his predecessor, Enrique Peña Nieto. And it has happened despite the combined budgets of the armed forces — the Ministries of Defense, Navy and the National Guard — being boosted by 150%.

“This government had the largest legal tools, institutional backup and budget than any other administration, and all the numbers are the worst,” said independent Senator Emilio Alvarez Icaza. “We’re seeing the worst numbers in homicides, in disappeared, in femicide. So the question is, what did they do?”

Nearly all of the extra funds AMLO’s administration provided to the military were directed to refashioning the armed forces into a construction behemoth, according to an analysis by Bloomberg News and Presupuesta Policy Consulting SA. This is the most in-depth assessment of the military’s resources and spending priorities to date. Meanwhile, as heists, kidnappings and extortions proliferated, the budget to train and deploy soldiers remained practically unchanged in real terms.

A separate public security ministry — which finances certain civilian-run public security efforts including the federal prison system — spent nearly 55% less during Lopez Obrador’s administration than Peña Nieto’s, and roughly 12% less than during Calderon’s term. The ministry receives funding for the National Guard, which Bloomberg did not include in this calculation since it is operated by the military.

While the president is flanked by top brass from Mexico’s Defense Ministry and Navy at various ribbon cuttings, cartels have been left to effectively run pockets of Mexican society. They charge locals for everything from Wi-Fi connections to water usage and even the right to have a party. Since the start of this year’s presidential election season on March 1, nearly 400 people connected to politics have been threatened or kidnapped, according to Mexico City-based consultancy Integralia. At least 24 have been murdered.

All of that has made public safety a top issue for voters. One recent poll said 46% feel security has gotten worse during AMLO’s term, and 74% think the government is very corrupt. It’s also ratcheted up tensions with the US, where migration across its southern border with Mexico and the influx of fentanyl-laced drugs are top issues in the presidential race between Joe Biden and Donald Trump.

That leaves Mexico’s next president — be it AMLO’s protégé and overwhelming favorite Claudia Sheinbaum or opposition candidate Xochitl Galvez — with limited options for reining in the military’s spending and reach, at least in the short term. In 2022, AMLO changed the constitution to allow the military to handle public security until at least 2028.

“He made it really hard for the next administration to walk everything back unless they have a wide majority in congress,” said Lisa Sanchez, head of Mexico Unido Contra la Delincuencia, a think tank that published a report called The Business of Militarization. “Their economic and political empowerment carries other risks — they’re a much more powerful force than they used to be.”

The President’s office and the Defense Ministry did not respond to a request for comment on this article. “There’s talk that the army and the navy are involved in everything,” Lopez Obrador said during one of his regular morning press conferences in January. “It’s not about militarizing the country. It’s about relying on two institutions that are pillars of the Mexican nation and that have helped us deliver in our responsibility to govern.”

In an interview, Arturo Zaldivar, the former head of the Supreme Court who is now helping Sheinbaum design her security strategy, said that “the armed forces have always been loyal in Mexico,” but as far as infrastructure-building goes, “we’d maybe have to re-calculate the role these institutions have. It was important for them to intervene, and we’ll have to see if there’s reason for them to stay.”

On Friday, during Acapulco’s Banking Convention, Sheinbaum said she did believe the National Guard — whose members can be seen patrolling Mexico City’s subways and beaches all over the country — should remain under the Secretary of Defense while existing separate from the army. However, she said she hasn’t yet determined whether several state-owned companies will remain under the armed forces’ jurisdiction or be placed in civilian hands.

“Whoever wins, Xochitl or Claudia, is going to face a lot of problems in ruling this country,” said Maria Elena Morera, activist and head of Causa en Comun AC, a nonprofit that studies security and other issues. “With the military, they have so much power now — maybe they can reach an agreement that’s good for them. But it’s going to be hard to take away all those businesses, and they were the ones who really insisted in handling the country’s security.”

The Public Budget

The program had a very official-sounding name: “National Security Government Infrastructure Projects.” But rather than funding infrastructure works that serve the public like a train line or new airport, the investment program funds upgrades and expansions of the military's footprint.

During AMLO’s administration, the Defense Ministry used the funding to build new air and military bases and remodeled and expanded military hospitals, according to Bloomberg’s analysis of military spending. It also modified a ranch to include an equine reproduction center, added a cargo elevator for a gym at its headquarters in Lomas de Sotelo in Mexico City and built a diving center in Cozumel, among other projects.

What’s also notable is that the military ultimately spent 288% more for the program than the 35.4 billion pesos, or about $2.1 billion, that Congress originally approved from 2019 to 2022. That meant the military infrastructure program accounted for 22% of the Defense Ministry’s annual budget, a leap from the 1% to 3% that was typically allocated during the Calderon and Peña Nieto years.

The Navy’s National Security Government Infrastructure Projects program, meanwhile, now only accounts for 1.5% of its ministry’s overall budget. That’s less than the 2.5% during the Calderon years and the 4.3% during the Peña Nieto era.

The Defense ministry was able to spend more than was allotted for such projects through what’s known as an amendment — a tool that lets a ministry change the budget without Congress’s approval, as is the case in many other countries. Congress is only informed about amendments in rare circumstances where the changes exceed 5% of a given governmental branch’s budget, according to Aura Martinez, an information coordinator at the Global Initiative for Fiscal Transparency.

Defense has been an avid user of amendments, spending 27% more than Congress approved from 2019 to 2022, according to the analysis.

“We’d never seen so many spending mechanisms made available to the armed forces as we’re seeing now,” Sanchez said. “Defense’s overspending equals all of the Labor Ministry’s annual budget.”

While he’s spending more on the military, Lopez Obrador’s priorities have differed from those of his predecessors. Historically, Mexican presidents have devoted nearly 50% of the Defense administration’s budget to training, recruiting and deploying soldiers, and buying weapons. Under Lopez Obrador’s administration, that share of the budget, in real terms, will have fallen to 17%.

Instead, 51% of the Defense and Navy’s combined budgets of 331 billion pesos in 2024 was earmarked for infrastructure projects.

Nearly half of the 259 billion pesos that Defense got this year will be used to finish the third of the Maya Train line it’s in charge of building. The railway is designed to ferry passengers between tourism hotspots like Cancun and Merida, and to hotels the military is building and operating deep in the Mayan jungle.

Another chunk will go to operating the new state-owned airline as well as managing airports near Mexico City and Tulum.

Much of the military’s business operations are housed under a government-run company called Grupo Aeroportuario, Ferroviario, de Servicios Auxiliares y Conexos, Olmeca-Maya-Mexica SA — better known as Gafsacomm. AMLO created the conglomerate in 2022 to oversee most government-built infrastructure projects and handed over its operation to the Defense Ministry. Its budget this year of 15 billion pesos will help it operate 12 airports, five hotels, three natural parks, two trains, a museum and the Mexicana airline.

Hardly anyone expects the airports or the airline to turn a profit in the near future. While the group’s losses will be covered by public coffers, it will get to keep any profit it does make and redirect it to the military’s pension system.

“The trend is that increasingly, the armed forces are going to have different money-making streams,” said Sanchez. “And that’s dangerous because you’re giving more money to an armed corporation that has a legitimate use of power and 400,000 soldiers.”

Lopez Obrador sees the projects as a way to develop the economy of traditionally poor parts of the country, which will create more employment and lead to better conditions, ultimately improving public safety. And the military has to be in charge of it all because, in the president’s view, it’s able to rise above the corruption that plagues civilian agencies handling funds for major projects. The military can deliver at a fraction of the cost of a private company and in a much shorter time, he says.

The Shadow Budget

There are several other, less transparent ways that Mexico’s armed forces receive funds to oversee infrastructure works.

The Defense and Navy control trusts in which they or other entities can deposit money without being required to disclose where the funds came from or how they’re being used. At the end of 2023, trusts administrated by the military held 81 billion pesos, compared with 7 billion pesos at the end of Peña Nieto’s government in 2018, according to nonprofit Mexico Evalua.

Given the lack of disclosure, there’s no way to know how much of the money in the trusts is accounted for in the budget.

“The exorbitant sum of it all and the risk of double counting are exactly why they should tell us what’s in there,” said Sanchez.

Then there are contracts. Between 2019 and 2022, the Defense Ministry received an additional 191 billion pesos through agreements with other federal ministries for public projects including the Maya Train, according to the nonprofit Mexican Institute of Competitiveness, known as IMCO.

Contracts are rarely made public and increasingly difficult to track, given Lopez Obrador’s near dismantling of transparency watchdog, the National Institute for Access to Public Information and Data Protection. IMCO obtained the information through government information requests and legal challenges.

“We’re facing an opacity monster,” said Paula Villaseñor, the former head of IMCO’s Effective Government division. “It’s incredibly hard to know how much money and contracts they have.”

Sara Velazquez, the lead author of a report called “National Inventory of the Militarized,” said the military receives money from so many sources that it’s nearly impossible to trace all of it.

“I think even they don’t know how much money they get every year,” she said.

Record Murders

Mexico’s official crime statistics are known to be far from exact. The country’s “cifra negra,” or the estimated share of crimes that go unreported, reached 92% in 2022, according to statistics agency Instituto Nacional de Estadistica y Geografia. Homicides, though slightly down from the first few years of Lopez Obrador’s administration, are on track to end up the highest ever in a presidential term. The Secretariado Ejecutivo del Sistema Nacional de Seguridad Publica (SESNSP), which is separate from Inegi, has counted 170,959 homicides with intent since AMLO took office through February of this year.

The president has acknowledged that homicides have surpassed those in previous administrations, but he casts blame on the violent country he inherited. Homicides fell 7% between 2021 and 2022, and dropped 4% between 2022 and 2023, which Lopez Obrador said was a direct reflection of his security strategy.

“It’s crazy to think that what we used to consider a violent year was one with 20,000 victims of homicide with intent,” said Lilian Chapa, a public-policy analyst who served as an adviser to SESNSP. The registry counted 29,705 homicides with intent in 2023.

National Guard Does It All

Last year, security consultant Manuel Garza witnessed the biggest heist he had seen in two decades. A shipment of mainly electronic goods worth nearly 17 million pesos was traveling along the highway from the port of Veracruz through the central state of Puebla. The person monitoring it on a screen suddenly saw the dot freeze.

An alert was raised when the dot hadn’t moved in over 40 minutes, said Garza, who is being identified using a pseudonym to protect him from retaliation. When the company’s private car came to check the scene, the truck’s security team of two armed guards were nowhere to be found.

The National Guard showed up 30 minutes later. When the truck’s driver called from the neighboring state of Hidalgo, he said he and the two guards had been tied up. But the National Guard didn’t take down the witnesses’ statements. For that, the security company had to go to the local prosecutor’s office. They got back nothing else from the heist.

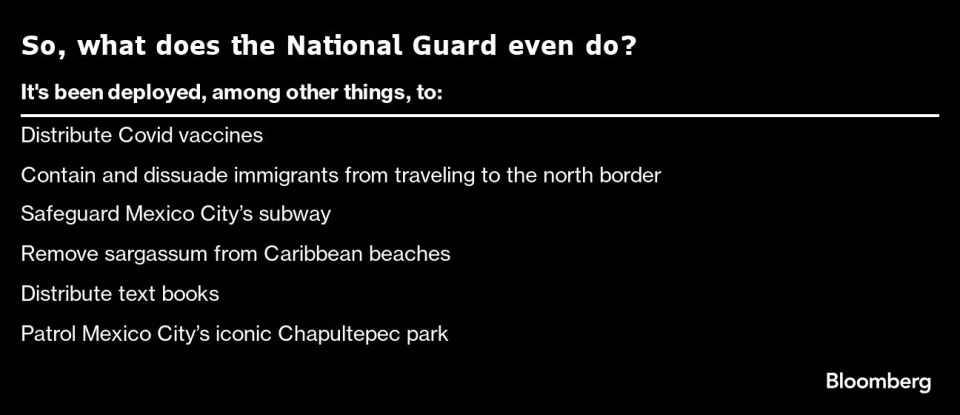

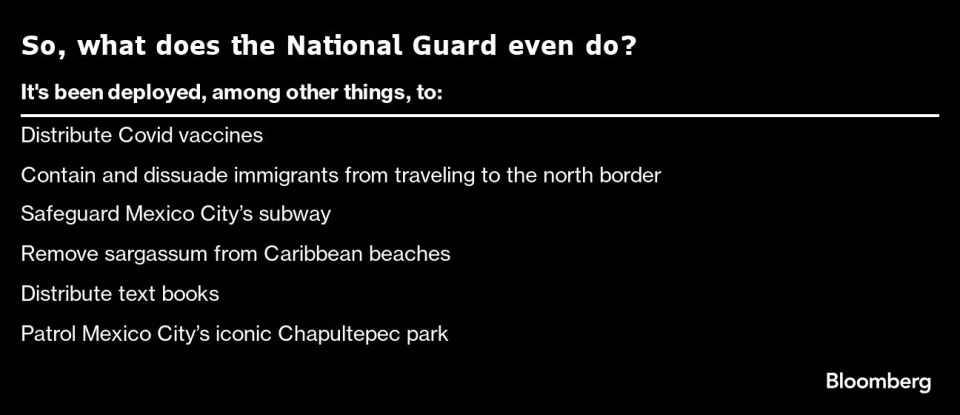

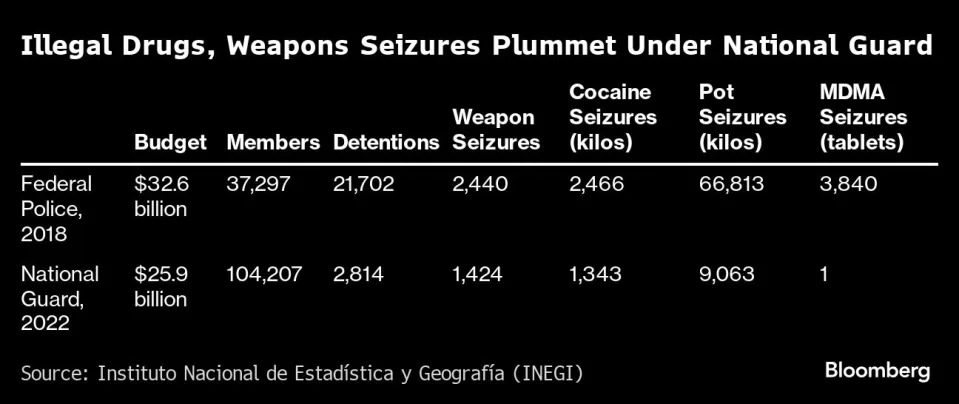

The episode is emblematic of how the military has frequently taken a halfhearted approach to law-enforcement responsibilities it inherited when the Mexican government did away with the Federal Police in 2019.

The National Guard had a total headcount of about 104,000 at the end of 2022. That includes 17,419 members drawn from the disbanded Federal Police and 1,050 new recruits. However, the majority of the force is made up of soldiers and marines on loan from the Defense and Navy. The troops were given new uniforms and armbands, but little to no training on how to do police work.

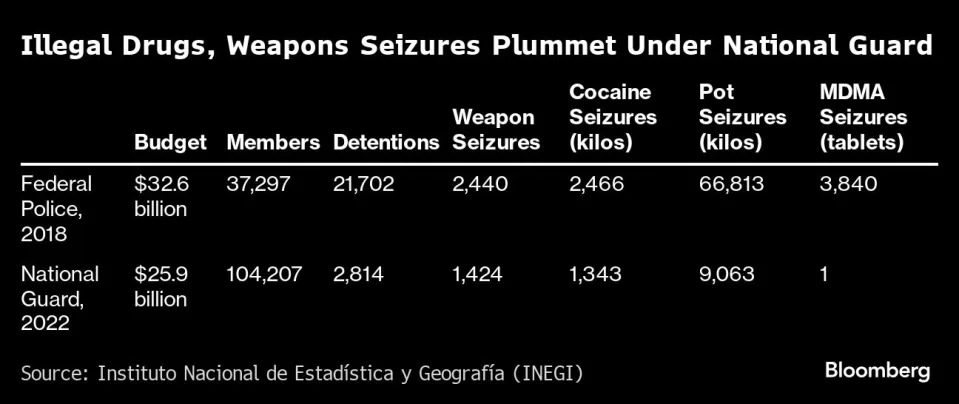

That has led to plummeting arrests as many National Guard members prefer to turn a blind eye to whatever crime is happening before them than go through the motions of properly arresting a suspect and filing the report correctly, according to Chapa, the public-policy analyst. Seizures of illegal drugs and weapons have plummeted as a result.

Guillermo Montes, who also asked to use a pseudonym, was one of the marines transferred to the National Guard. He saw many of his fellow guardsmen make mistakes when they intervened at the scene of a crime because they had no idea how to track down robbers or respond to 911 calls.

One of the hardest things to do, he recalled, was present evidence in front of a judge. Often, their cases were dismissed on procedural grounds, since they hadn’t been fully trained on the protocols of filling out police reports.

“The armed forces are not trained to be police,” he said. “We followed in order to help, but we were lacking many of the things that the police know.”

Lopez Obrador didn’t always back such broad use of the armed forces. He had been vocal about sending the military “back to its barracks” since losing the 2006 presidential election against Calderon, who had the armed forces take to the streets to fight cartels. That resulted in more than 103,000 homicides during his administration.

“We can’t solve the country’s insecurity and violence with the army,” Lopez Obrador said in a video dated 2010. “We can’t use the military to make up for the civilian government’s shortcomings. It’s important we don’t give the army excessive faculties — we can’t accept a militarist government.”

But it didn’t take long for him to change his mind. In regular meetings during his transition into office, the Defense Ministry’s top brass laid out how corrupt the Federal Police was and how the military was the only institution worthy of his trust, according to a person familiar with the situation.

The Federal Police were plagued by reports of abuse of power, torture and corruption. Last year, Genaro Garcia Luna, who had been in charge of Mexico’s battle to root out illegal narcotics and vanquish drug kingpins, was convicted by a federal jury in New York of helping Sinaloa cartel members import and distribute drugs in the US. His defense has requested a new trial.

Though AMLO initially presented the National Guard as a civilian force, it’s effectively operated by the Defense Ministry, and its budget is routinely transferred to the military. In August 2022, Lopez Obrador issued a decree to place the guard under the Defense Ministry.

In April 2023, Mexico’s top court said that decree was unconstitutional, and gave the government until Jan. 1, 2024 to return the operation of the guard to the civilian ministry.

AMLO has said he would abide by the court’s order, but in February, he sent a new proposal to Congress to officially move the National Guard to Defense. Congress has yet to pass it.

“We’re living in two worlds,” said Ernesto Lopez Portillo, former member of Mexico City’s Human Rights Commission and head of Universidad Iberoamericana’s Citizen Security program. “The world of the constitution that says public security is a civilian matter” and “the world of reality, where the National Guard is, under every indicator that we have, strictly military.”

Money and Power

Sheinbaum has said she intends to consolidate the National Guard, and following AMLO’s footsteps, that it should operate under the Defense Ministry.

Meanwhile, Galvez has said the military has been asked to do too many things unrelated to their core mission.

“They shouldn’t be building trains, patrolling parks or handing out books,” she said at an event in Campeche in March. “A large part of the country is in the hands of criminals these days, we need the military to return to its national security activities.”

Mexico’s militarization isn’t exclusive to the federal government, according Causa en Comun's Morera. Military and Navy officials now oversee public-security ministries in 17 of the country’s 32 states. Sixteen of those states are ruled by AMLO’s Morena party.

For whoever wins Mexico’s presidential election on June 2, the key question will be how to deal with an empowered, enlarged and wealthy military that has taken over hundreds of tasks that used to be in the hands of civilians — and that has more revenue streams than ever — while reining in the record-breaking number of homicides.

“They’ve overused a perverse blanket called national security,” said Senator Alvarez Icaza. “Now the dilemma is, how do we take away all the money and power that Lopez Obrador gave them?”

--With assistance from Maya Averbuch, Rafael Gayol and Michael O'Boyle.

Andrea Navarro

Fri, April 19, 2024

In his six years as Mexico’s president, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador gave his country’s military two important jobs: build infrastructure works to supercharge the economy and rein in violent crime.

By the end of his presidency, he will have accomplished only one — and left the other worse than ever.

AMLO, as the president is known, has used Mexico’s armed forces to build airports, construct a nearly 1,000-mile long railroad through the Mayan jungle, and create a state-owned airline. Those initiatives are likely to burnish his economic legacy as he prepares to leave office following this June’s presidential election.

Yet Lopez Obrador will leave another legacy as well. His administration has presided over the bloodiest term in the nation’s recent history, with more than 170,000 homicides since he took office in 2018 through February. That is a 26% increase from the 135,345 murders during the term of his predecessor, Enrique Peña Nieto. And it has happened despite the combined budgets of the armed forces — the Ministries of Defense, Navy and the National Guard — being boosted by 150%.

“This government had the largest legal tools, institutional backup and budget than any other administration, and all the numbers are the worst,” said independent Senator Emilio Alvarez Icaza. “We’re seeing the worst numbers in homicides, in disappeared, in femicide. So the question is, what did they do?”

Nearly all of the extra funds AMLO’s administration provided to the military were directed to refashioning the armed forces into a construction behemoth, according to an analysis by Bloomberg News and Presupuesta Policy Consulting SA. This is the most in-depth assessment of the military’s resources and spending priorities to date. Meanwhile, as heists, kidnappings and extortions proliferated, the budget to train and deploy soldiers remained practically unchanged in real terms.

A separate public security ministry — which finances certain civilian-run public security efforts including the federal prison system — spent nearly 55% less during Lopez Obrador’s administration than Peña Nieto’s, and roughly 12% less than during Calderon’s term. The ministry receives funding for the National Guard, which Bloomberg did not include in this calculation since it is operated by the military.

While the president is flanked by top brass from Mexico’s Defense Ministry and Navy at various ribbon cuttings, cartels have been left to effectively run pockets of Mexican society. They charge locals for everything from Wi-Fi connections to water usage and even the right to have a party. Since the start of this year’s presidential election season on March 1, nearly 400 people connected to politics have been threatened or kidnapped, according to Mexico City-based consultancy Integralia. At least 24 have been murdered.

All of that has made public safety a top issue for voters. One recent poll said 46% feel security has gotten worse during AMLO’s term, and 74% think the government is very corrupt. It’s also ratcheted up tensions with the US, where migration across its southern border with Mexico and the influx of fentanyl-laced drugs are top issues in the presidential race between Joe Biden and Donald Trump.

That leaves Mexico’s next president — be it AMLO’s protégé and overwhelming favorite Claudia Sheinbaum or opposition candidate Xochitl Galvez — with limited options for reining in the military’s spending and reach, at least in the short term. In 2022, AMLO changed the constitution to allow the military to handle public security until at least 2028.

“He made it really hard for the next administration to walk everything back unless they have a wide majority in congress,” said Lisa Sanchez, head of Mexico Unido Contra la Delincuencia, a think tank that published a report called The Business of Militarization. “Their economic and political empowerment carries other risks — they’re a much more powerful force than they used to be.”

The President’s office and the Defense Ministry did not respond to a request for comment on this article. “There’s talk that the army and the navy are involved in everything,” Lopez Obrador said during one of his regular morning press conferences in January. “It’s not about militarizing the country. It’s about relying on two institutions that are pillars of the Mexican nation and that have helped us deliver in our responsibility to govern.”

In an interview, Arturo Zaldivar, the former head of the Supreme Court who is now helping Sheinbaum design her security strategy, said that “the armed forces have always been loyal in Mexico,” but as far as infrastructure-building goes, “we’d maybe have to re-calculate the role these institutions have. It was important for them to intervene, and we’ll have to see if there’s reason for them to stay.”

On Friday, during Acapulco’s Banking Convention, Sheinbaum said she did believe the National Guard — whose members can be seen patrolling Mexico City’s subways and beaches all over the country — should remain under the Secretary of Defense while existing separate from the army. However, she said she hasn’t yet determined whether several state-owned companies will remain under the armed forces’ jurisdiction or be placed in civilian hands.

“Whoever wins, Xochitl or Claudia, is going to face a lot of problems in ruling this country,” said Maria Elena Morera, activist and head of Causa en Comun AC, a nonprofit that studies security and other issues. “With the military, they have so much power now — maybe they can reach an agreement that’s good for them. But it’s going to be hard to take away all those businesses, and they were the ones who really insisted in handling the country’s security.”

The Public Budget

The program had a very official-sounding name: “National Security Government Infrastructure Projects.” But rather than funding infrastructure works that serve the public like a train line or new airport, the investment program funds upgrades and expansions of the military's footprint.

During AMLO’s administration, the Defense Ministry used the funding to build new air and military bases and remodeled and expanded military hospitals, according to Bloomberg’s analysis of military spending. It also modified a ranch to include an equine reproduction center, added a cargo elevator for a gym at its headquarters in Lomas de Sotelo in Mexico City and built a diving center in Cozumel, among other projects.

What’s also notable is that the military ultimately spent 288% more for the program than the 35.4 billion pesos, or about $2.1 billion, that Congress originally approved from 2019 to 2022. That meant the military infrastructure program accounted for 22% of the Defense Ministry’s annual budget, a leap from the 1% to 3% that was typically allocated during the Calderon and Peña Nieto years.

The Navy’s National Security Government Infrastructure Projects program, meanwhile, now only accounts for 1.5% of its ministry’s overall budget. That’s less than the 2.5% during the Calderon years and the 4.3% during the Peña Nieto era.

The Defense ministry was able to spend more than was allotted for such projects through what’s known as an amendment — a tool that lets a ministry change the budget without Congress’s approval, as is the case in many other countries. Congress is only informed about amendments in rare circumstances where the changes exceed 5% of a given governmental branch’s budget, according to Aura Martinez, an information coordinator at the Global Initiative for Fiscal Transparency.

Defense has been an avid user of amendments, spending 27% more than Congress approved from 2019 to 2022, according to the analysis.

“We’d never seen so many spending mechanisms made available to the armed forces as we’re seeing now,” Sanchez said. “Defense’s overspending equals all of the Labor Ministry’s annual budget.”

While he’s spending more on the military, Lopez Obrador’s priorities have differed from those of his predecessors. Historically, Mexican presidents have devoted nearly 50% of the Defense administration’s budget to training, recruiting and deploying soldiers, and buying weapons. Under Lopez Obrador’s administration, that share of the budget, in real terms, will have fallen to 17%.

Instead, 51% of the Defense and Navy’s combined budgets of 331 billion pesos in 2024 was earmarked for infrastructure projects.

Nearly half of the 259 billion pesos that Defense got this year will be used to finish the third of the Maya Train line it’s in charge of building. The railway is designed to ferry passengers between tourism hotspots like Cancun and Merida, and to hotels the military is building and operating deep in the Mayan jungle.

Another chunk will go to operating the new state-owned airline as well as managing airports near Mexico City and Tulum.

Much of the military’s business operations are housed under a government-run company called Grupo Aeroportuario, Ferroviario, de Servicios Auxiliares y Conexos, Olmeca-Maya-Mexica SA — better known as Gafsacomm. AMLO created the conglomerate in 2022 to oversee most government-built infrastructure projects and handed over its operation to the Defense Ministry. Its budget this year of 15 billion pesos will help it operate 12 airports, five hotels, three natural parks, two trains, a museum and the Mexicana airline.

Hardly anyone expects the airports or the airline to turn a profit in the near future. While the group’s losses will be covered by public coffers, it will get to keep any profit it does make and redirect it to the military’s pension system.

“The trend is that increasingly, the armed forces are going to have different money-making streams,” said Sanchez. “And that’s dangerous because you’re giving more money to an armed corporation that has a legitimate use of power and 400,000 soldiers.”

Lopez Obrador sees the projects as a way to develop the economy of traditionally poor parts of the country, which will create more employment and lead to better conditions, ultimately improving public safety. And the military has to be in charge of it all because, in the president’s view, it’s able to rise above the corruption that plagues civilian agencies handling funds for major projects. The military can deliver at a fraction of the cost of a private company and in a much shorter time, he says.

The Shadow Budget

There are several other, less transparent ways that Mexico’s armed forces receive funds to oversee infrastructure works.

The Defense and Navy control trusts in which they or other entities can deposit money without being required to disclose where the funds came from or how they’re being used. At the end of 2023, trusts administrated by the military held 81 billion pesos, compared with 7 billion pesos at the end of Peña Nieto’s government in 2018, according to nonprofit Mexico Evalua.

Given the lack of disclosure, there’s no way to know how much of the money in the trusts is accounted for in the budget.

“The exorbitant sum of it all and the risk of double counting are exactly why they should tell us what’s in there,” said Sanchez.

Then there are contracts. Between 2019 and 2022, the Defense Ministry received an additional 191 billion pesos through agreements with other federal ministries for public projects including the Maya Train, according to the nonprofit Mexican Institute of Competitiveness, known as IMCO.

Contracts are rarely made public and increasingly difficult to track, given Lopez Obrador’s near dismantling of transparency watchdog, the National Institute for Access to Public Information and Data Protection. IMCO obtained the information through government information requests and legal challenges.

“We’re facing an opacity monster,” said Paula Villaseñor, the former head of IMCO’s Effective Government division. “It’s incredibly hard to know how much money and contracts they have.”

Sara Velazquez, the lead author of a report called “National Inventory of the Militarized,” said the military receives money from so many sources that it’s nearly impossible to trace all of it.

“I think even they don’t know how much money they get every year,” she said.

Record Murders

Mexico’s official crime statistics are known to be far from exact. The country’s “cifra negra,” or the estimated share of crimes that go unreported, reached 92% in 2022, according to statistics agency Instituto Nacional de Estadistica y Geografia. Homicides, though slightly down from the first few years of Lopez Obrador’s administration, are on track to end up the highest ever in a presidential term. The Secretariado Ejecutivo del Sistema Nacional de Seguridad Publica (SESNSP), which is separate from Inegi, has counted 170,959 homicides with intent since AMLO took office through February of this year.

The president has acknowledged that homicides have surpassed those in previous administrations, but he casts blame on the violent country he inherited. Homicides fell 7% between 2021 and 2022, and dropped 4% between 2022 and 2023, which Lopez Obrador said was a direct reflection of his security strategy.

“It’s crazy to think that what we used to consider a violent year was one with 20,000 victims of homicide with intent,” said Lilian Chapa, a public-policy analyst who served as an adviser to SESNSP. The registry counted 29,705 homicides with intent in 2023.

National Guard Does It All

Last year, security consultant Manuel Garza witnessed the biggest heist he had seen in two decades. A shipment of mainly electronic goods worth nearly 17 million pesos was traveling along the highway from the port of Veracruz through the central state of Puebla. The person monitoring it on a screen suddenly saw the dot freeze.

An alert was raised when the dot hadn’t moved in over 40 minutes, said Garza, who is being identified using a pseudonym to protect him from retaliation. When the company’s private car came to check the scene, the truck’s security team of two armed guards were nowhere to be found.

The National Guard showed up 30 minutes later. When the truck’s driver called from the neighboring state of Hidalgo, he said he and the two guards had been tied up. But the National Guard didn’t take down the witnesses’ statements. For that, the security company had to go to the local prosecutor’s office. They got back nothing else from the heist.

The episode is emblematic of how the military has frequently taken a halfhearted approach to law-enforcement responsibilities it inherited when the Mexican government did away with the Federal Police in 2019.

The National Guard had a total headcount of about 104,000 at the end of 2022. That includes 17,419 members drawn from the disbanded Federal Police and 1,050 new recruits. However, the majority of the force is made up of soldiers and marines on loan from the Defense and Navy. The troops were given new uniforms and armbands, but little to no training on how to do police work.

That has led to plummeting arrests as many National Guard members prefer to turn a blind eye to whatever crime is happening before them than go through the motions of properly arresting a suspect and filing the report correctly, according to Chapa, the public-policy analyst. Seizures of illegal drugs and weapons have plummeted as a result.

Guillermo Montes, who also asked to use a pseudonym, was one of the marines transferred to the National Guard. He saw many of his fellow guardsmen make mistakes when they intervened at the scene of a crime because they had no idea how to track down robbers or respond to 911 calls.

One of the hardest things to do, he recalled, was present evidence in front of a judge. Often, their cases were dismissed on procedural grounds, since they hadn’t been fully trained on the protocols of filling out police reports.

“The armed forces are not trained to be police,” he said. “We followed in order to help, but we were lacking many of the things that the police know.”

Lopez Obrador didn’t always back such broad use of the armed forces. He had been vocal about sending the military “back to its barracks” since losing the 2006 presidential election against Calderon, who had the armed forces take to the streets to fight cartels. That resulted in more than 103,000 homicides during his administration.

“We can’t solve the country’s insecurity and violence with the army,” Lopez Obrador said in a video dated 2010. “We can’t use the military to make up for the civilian government’s shortcomings. It’s important we don’t give the army excessive faculties — we can’t accept a militarist government.”

But it didn’t take long for him to change his mind. In regular meetings during his transition into office, the Defense Ministry’s top brass laid out how corrupt the Federal Police was and how the military was the only institution worthy of his trust, according to a person familiar with the situation.

The Federal Police were plagued by reports of abuse of power, torture and corruption. Last year, Genaro Garcia Luna, who had been in charge of Mexico’s battle to root out illegal narcotics and vanquish drug kingpins, was convicted by a federal jury in New York of helping Sinaloa cartel members import and distribute drugs in the US. His defense has requested a new trial.

Though AMLO initially presented the National Guard as a civilian force, it’s effectively operated by the Defense Ministry, and its budget is routinely transferred to the military. In August 2022, Lopez Obrador issued a decree to place the guard under the Defense Ministry.

In April 2023, Mexico’s top court said that decree was unconstitutional, and gave the government until Jan. 1, 2024 to return the operation of the guard to the civilian ministry.

AMLO has said he would abide by the court’s order, but in February, he sent a new proposal to Congress to officially move the National Guard to Defense. Congress has yet to pass it.

“We’re living in two worlds,” said Ernesto Lopez Portillo, former member of Mexico City’s Human Rights Commission and head of Universidad Iberoamericana’s Citizen Security program. “The world of the constitution that says public security is a civilian matter” and “the world of reality, where the National Guard is, under every indicator that we have, strictly military.”

Money and Power

Sheinbaum has said she intends to consolidate the National Guard, and following AMLO’s footsteps, that it should operate under the Defense Ministry.

Meanwhile, Galvez has said the military has been asked to do too many things unrelated to their core mission.

“They shouldn’t be building trains, patrolling parks or handing out books,” she said at an event in Campeche in March. “A large part of the country is in the hands of criminals these days, we need the military to return to its national security activities.”

Mexico’s militarization isn’t exclusive to the federal government, according Causa en Comun's Morera. Military and Navy officials now oversee public-security ministries in 17 of the country’s 32 states. Sixteen of those states are ruled by AMLO’s Morena party.

For whoever wins Mexico’s presidential election on June 2, the key question will be how to deal with an empowered, enlarged and wealthy military that has taken over hundreds of tasks that used to be in the hands of civilians — and that has more revenue streams than ever — while reining in the record-breaking number of homicides.

“They’ve overused a perverse blanket called national security,” said Senator Alvarez Icaza. “Now the dilemma is, how do we take away all the money and power that Lopez Obrador gave them?”

--With assistance from Maya Averbuch, Rafael Gayol and Michael O'Boyle.