Bankers reassessing accelerating climate crisis in anticipation of trillions of dollars of annual damage

As global temperatures continue to rise, banks are facing growing financial risks associated with the changing climate and have switched their focus from selling things like green bonds to trying to assess their exposure to possible trillions of dollars of damage hurricanes and floods will cause in the coming years.

A new study from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) publication Nature warns that climate change up to 2050 could do $38 trillion in damage and knock a fifth off global income.

Under worse-case scenarios based on current emissions trajectories, temperatures will miss the 1.5C cap and rise by 3C to 4C, which will have disastrous impact on many countries.

Potsdam’s central scenario is that the global economy could face $38 trillion a year of climate damages a year by 2050, which would knock 19% off projected per capita incomes and that much of that damage is already locked in even if emissions start to fall now. Under the worst-case scenario the study found that the damage could rise to $59 trillion by 2050 and incomes would fall by 60%.

The report concluded: "Our analysis shows that climate change will cause massive economic damages within the next 25 years in almost all countries around the world, including highly developed ones such as Germany, France and the United States."

However, the extent to of the damage and how it manifests itself remains an open question, due to the myriad uncertainties associate with the Climate Crisis, which is why banks are starting to tool and man up with staff to assess the risks.

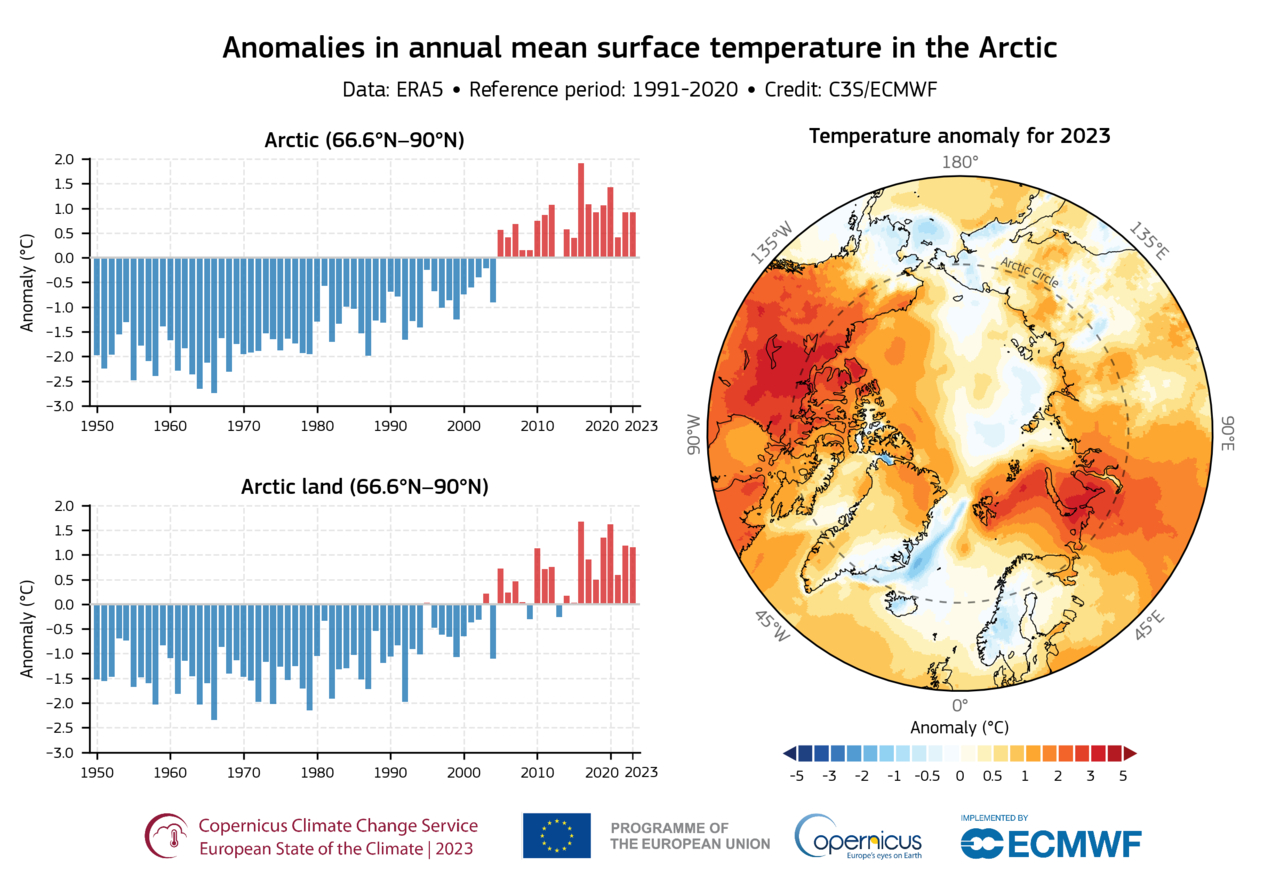

As 2023 starts, the all-time record extreme records are already being smashed on a daily basis as the world moves into uncharted territory, a paper published by Oxford Academic warned in December that tracks the climate vital signs: 20 of the 35 indicators are already flashing red.

According to the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, the potential economic shocks of global warming could significantly impair banks' balance sheets and even threaten the overall stability of the banking sector in the annual disaster seasons that appeared last year.

Initially banks concentrated on so-called transition risks related to asset value changes and costs linked to global decarbonisation efforts. However, the growing frequency of extreme weather events has shifted their focus towards more immediate physical risks.

For example, bankers were caught off guard after the first ever category five hurricane hit Acapulco last year, virtually destroying the popular tourist seaside resort town that was ill-prepared for such a strong storm. Floods have also become common around the world due to higher rainfall that is a consequence of global warming, and threaten to sweep entire towns and villages on big river banks away.

So far, the worst disasters have hit emerging markets. Countries in the tropics will suffer the most because they are already warmer. The irony is that the countries least responsible for climate change are the ones likely to suffer the worst damage, and the ones that are most responsible will suffer the least.

But some more developed countries have already found themselves in the front line. Last year saw massive flooding in Greece that devastated the country’s agricultural sector and did damage that will take five or more years to repair, if there are no more storms.

European farms have also warned of a “harvest catastrophe” this year as temperatures on the Continent have seesawed between the hottest ever days on record for early April, before northern Europe was plunged into a cold snap in the second half of the month that saw unseasonal snowfall in Belgium.

European farmers who were unable to plant winter crops last autumn had been banking on a dry spring this year to be able to plant those same fields with springs crops, but have been met with a quagmire. The prospects of establishing spring crops are looking increasingly slim, which will have an impact on European grain yields this year and hence prices.

Heavy rainfall over the last fortnight is increasing farmers’ concerns as it follows relentless rain since October, and there is more heavy rainfall on the horizon. This year’s harvest prospects are looking bleak.

And in a sign of things to come, in Dubai things were even more extreme when an entire year’s worth of rain fell in a single day, turning the capital of the normally arid United Arab Emirates (UAE) into a lake.

Extreme weather is something that is starting to have an impact on entire economies and which banks are beginning to feel forced to factor into their regular stocks and bonds analysis. Devastating floods in Pakistan in 2022 erased 2.2% of the country's GDP. Canada's severe wildfire season in 2023 and a significant drought at the Panama Canal affected growth and international trade in a measurable way, and disrupted a critical global trade route handling $270bn annually.

To better prepare for these environmental threats, JPMorgan has been bolstering its workforce, including hiring catastrophe modellers to assess potential impacts on its real estate portfolios. And a December report by BloombergNEF revealed that extreme climate events can severely affect companies up to the point of bankruptcy. Still, many are still not fully aware of their vulnerability as analysts race to catch up with the pace of change. Bloomberg’s study showed that 65% of over 2,000 companies analysed did not recognise potential physical risks in their operations, and even fewer conducted financial assessments of these risks.

Citigroup has also acknowledged the broad spectrum of risks posed by climate change, Bloomberg reports, including credit, liquidity and operational risks. Last month, Citigroup introduced a Climate Risk Heat Map to evaluate the vulnerability of its credit exposures to climate-related risks, identifying its oil and gas production loan book, along with the semiconductor and ports sectors, as areas with high physical and transition risk scores.

The Potsdam report concluded that "protecting our climate is much cheaper than not doing so, and that is without even considering non-economic impacts such as loss of life or biodiversity".