THE CONVERSQTION

Published: April 25, 2024 4.02pm EDT

The hyper-arid desert of Eastern Sudan, the Atbai Desert, seems like an unlikely place to find evidence of ancient cattle herders. But in this dry environment, my new research has found rock art over 4,000 years old that depicts cattle.

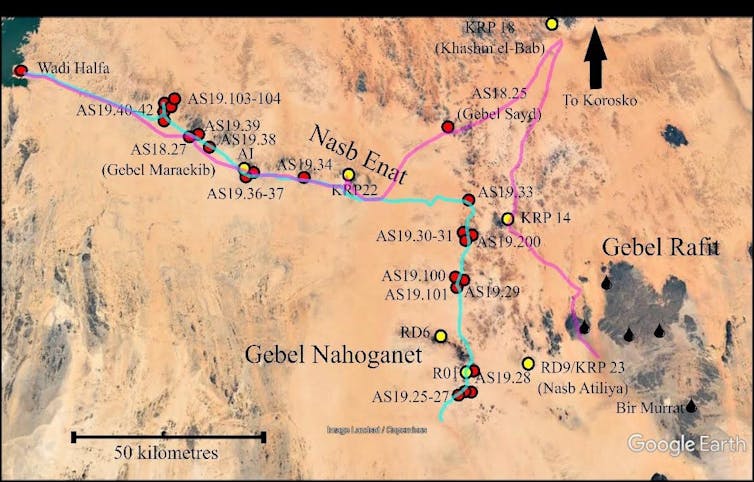

In 2018 and 2019, I led a team of archaeologists on the Atbai Survey Project. We discovered 16 new rock art sites east of the Sudanese city of Wadi Halfa, in one of the most desolate parts of the Sahara. This area receives almost no yearly rainfall.

Almost all of these rock art sites had one feature in common: the depiction of cattle, either as a lone cow or part of a larger herd.

On face value, this is a puzzling creature to find carved on desert rock walls. Cattle need plenty of water and acres of pasture, and would quickly perish today in such a sand-choked environment.

Written by academics, edited by journalists, backed by evidence.Get newsletter

In modern Sudan, cattle only occur about 600 kilometres to the south, where the northernmost latitudes of the African monsoon create ephemeral summer grasslands suitable for cattle herding.

The theme of cattle in ancient rock art is one of most important pieces of evidence establishing a bygone age of the “green Sahara”.

New sites discovered on surveys in Eastern Sudan. © The Atbai Survey Project

The ‘green Sahara’

Archaeological and climatic fieldwork across the entire Sahara, from Morocco to Sudan and everywhere in between, has illustrated a comprehensive picture of a region that used to be much wetter.

Climate scientists, archaeologists and geologists call this the “African humid period”. It was a time of increased summer monsoon rainfall across the continent, which began about 15,000 years ago and ended roughly 5,000 years ago.

The wastes of the Atbai Desert, north-east Sudan – a very different landscape to the ‘green Sahara’. Julien Cooper

This “green Sahara” is a vital period in human history. In North Africa, this was when agriculture began and livestock were domesticated.

In this small “wet gap”, around 8,000–7,000 years ago, local nomads adopted cattle and other livestock such as sheep and goats from their neighbours to the north in Egypt and the Middle East.

Read more: The Sahara Desert used to be a green savannah – new research explains why

A close human-animal connection

When the prehistoric artists painted cattle on their rock canvasses in what is now Sudan, the desert was a grassy savannah. It was brimming with pools, rivers, swamps and waterholes and typical African game such as elephants, rhinos and cheetah – very different to the deserts of today.

Cattle were not just a source of meat and milk. Close inspection of the rock art and in the archaeological record reveals these animals were modified by their owners. Horns were deformed, skin decorated and artificial folds fashioned on their neck, so-called “pendants”

A strong relationship between human and animal: a cow with a modified ‘neck’ pendant and horns. Julien Cooper

Cattle were even buried alongside humans in massive cemeteries, signalling an intimate link between person, animal and group identity.

The perils of climate change

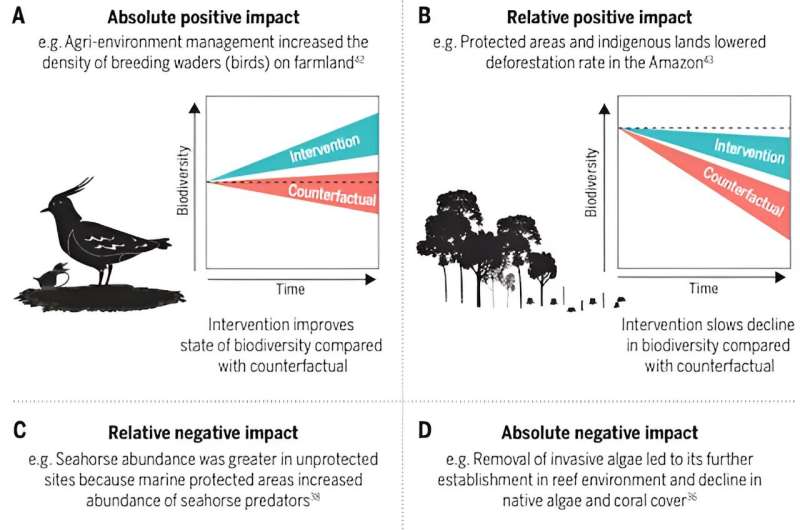

At the end of the “humid period”, around 3000 BCE, things began to worsen rapidly. Lakes and rivers dried up and sands swallowed dead pastures. Scientists debate how rapidly conditions worsened, and this seems to have differed greatly across specific subregions.

Local human populations had a choice – leave the desert or adapt to their new dry norms. For those that left the Sahara for wetter parts, the best refuge was the Nile. It is no accident that this rough period also eventuated in the rise of urban agricultural civilisations in Egypt and Sudan.

The most common image in the local rock art was of cattle. Julien Cooper

Some of the deserts, such as the Atbai Desert around Wadi Halfa where the rock art was discovered, became almost depopulated. Not even the hardiest of livestock could survive in such regions. For those who remained, cattle were abandoned for hardier sheep and goats (the camel would not be domesticated in North Africa for another 2,000–3,000 years).

This abandonment would have major ramifications on all aspects of human life: diet and lack of milk, migratory patterns of herding families and, for nomads so connected to their cattle, their very identity and ideology.

New phases of history

Archaeologists, who spend so much time on the ancient artefacts of the past, often forget our ancestors had emotions. They lived, loved and suffered just like we do. Abandoning an animal that was very much a core part of their identity, and with whom they shared an emotional connection, cannot have been easy for their emotions and sense of place in the world.

For those communities that migrated and lived on the Nile, cattle continued to be a symbol of identity and importance. At the ancient capital of Sudan, Kerma, community leaders were buried in elaborate graves girded by cattle skulls. One burial even had 4,899 skulls.

Today in South Sudan and much of the Horn of Africa, similar practices regarding cattle and their cultural prominence endure to the present. Here, just as in ancient Sahara, cattle are decorated, branded and have an important place in funeral traditions, with cattle skulls marking graves and cattle consumed in feasts.

As we move into a new phase of human history subject to rapid climate oscillations and environmental degradation, we need to ponder just how we will adapt beyond questions of economy and subsistence.

One of the most basic common denominators of culture is our relationship to our shared landscape. Environmental change, whether we like it or not, will force us to create new identities, symbols and meanings.

Read more: Innovations on the Nile over millennia offer lessons in engineering sustainable futures

Honorary Lecturer, Department of History and Archaeology, Macquarie University

Disclosure statement

Julien Cooper receives funding from the Australian Research Council and Macquarie University.