Preying on white fears worked in Georgia in the ’60s −and is working there for Trump today

In January 1967, after a gubernatorial election that saw neither candidate gain enough votes to win, the Georgia Legislature was faced with a vital decision: the selection of the state’s 75th governor during the height of the Civil Rights Movement.

Legislators chose the candidate who earned the least number of votes and was an ardent segregationist – Democrat Lester Maddox, owner of a chicken restaurant and a perennial candidate.

That transformation of Maddox from racist, eccentric business owner to governor was a historical note amid a backdrop of Southern politics and the region’s resentment of Black political gains. Southern politics was and is replete with colorful characters, hucksters, showmen and demagogues who managed both to shock and engender fierce loyalty among their followers.

Maddox showed that it was politically profitable to play on the fears and anxieties of white people, who were afraid of the political power of Black voters. And what was true in Georgia in the 1960s turns out to be true throughout the South today, as Maddox’s victory based on racism holds lessons for the 2024 presidential election.

To understand the popularity of Donald Trump and the Republican Party in Southern states such as Georgia, it’s crucial to understand the racial divisions that preceded him.

As a civil rights historian, I believe that Trump can be placed among a long line of demagogues who possess the skills needed to tap into the fears and anxieties of a group of people that perceives itself as marginalized, at risk and not in control.

Maddox was one of the first to do so in his successful gubernatorial campaign in 1966.

For ‘the little people’

In his book “The Demagogue’s Playbook,” law professor Eric Posner defined a demagogue as a “charismatic, amoral person who obtains the support of the people through dishonesty, emotional manipulation, and the exploitation of social divisions.”

For Maddox, a Democrat in the era when Southern Democrats were the segregationist party, the social division he could exploit was a rapidly changing South, where political and cultural conventions were turned upside down by the successes of the Civil Rights Movement. No longer was the white race the master of the social order.

During his campaign, Maddox used class warfare to frame his GOP opponent, millionaire textile heir Bo Callaway, as an elite integrationist who was out of touch with white voters – or as Maddox called them, “the little people.”

Atlanta cafeteria owner Lester Maddox, left, shoves one of several Black men who attempted to integrate his restaurant in 1964. Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Atlanta cafeteria owner Lester Maddox, left, shoves one of several Black men who attempted to integrate his restaurant in 1964. Bettmann Archive/Getty ImagesMaddox used newspaper advertisements for his chicken restaurant, the Pickrick, to rant about political grievances and target his political enemies.

But his primary weapon of choice was the race card. He celebrated his aggression toward Black people by brandishing axe handles as he stood in the doorway of his restaurant in downtown Atlanta.

A crass businessman, Maddox called his axe handles “Pickrick Drumsticks,” which he also sold for US$2 apiece.

Such brazen behavior earned Maddox the admiration of many white Georgians uneasy about the pace of racial integration. His popularity was solidified after he refused to allow Black people to eat in his chicken restaurant, as required under the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and literally chased them away from his front door.

At one point during the scuffle, Maddox was heard calling to the Black customers, “You no good dirty devils! You dirty Communists! Get the hell out of here or I’ll kill you.”

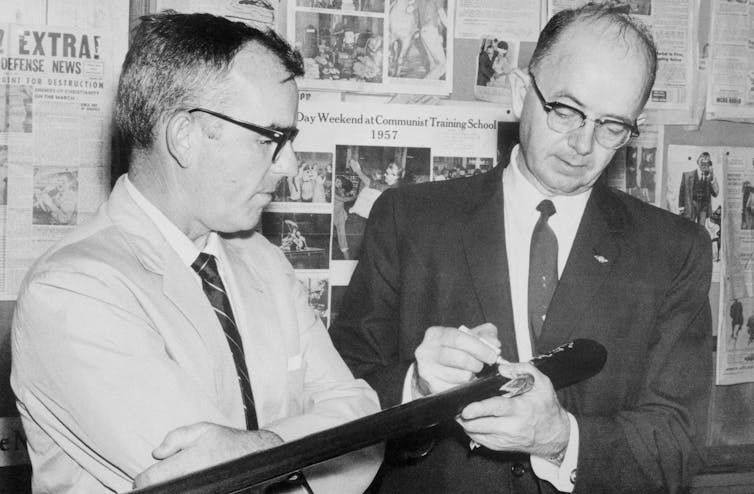

Lester Maddox autographs one of the axe handles that he sold for $2 in 1964. Bettmann/Getty Images

Lester Maddox autographs one of the axe handles that he sold for $2 in 1964. Bettmann/Getty ImagesWhen a Georgia court ordered Maddox to obey the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Maddox chose to shut down his business. For him, the issue was a matter of the rights of private property owners.

“This property belongs to me,” Maddox once said, “and I’ll throw out a white one, a black one, a red-headed one or a bald-headed one. It doesn’t make any difference to me.”

Maddox denied being a racist and defended his segregationist views by arguing he believed in separate but equal facilities for white and Black people.

Maddox served only one term as governor because state law prevented any governor serving two successive terms. Instead, he ran for lieutenant governor in 1970 and won.

Georgia on Trump’s mind

Much like Maddox, Trump has tapped into white resentment and anger to gain popularity in a state that he won in 2016 but barely lost in the 2020 presidential election.

In her book “Demagogue for President: The Rhetorical Genius of Donald Trump,” American rhetoric historian Jennifer Mercieca explains that Trump is “a leader who makes use of popular prejudices and false claims and promises in order to gain power.”

That is an effective strategy, she argued, especially with a frustrated and polarized electorate.

Donald Trump speaks during a campaign rally in Rome, Georgia, on March 9, 2024. Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Donald Trump speaks during a campaign rally in Rome, Georgia, on March 9, 2024. Chip Somodevilla/Getty ImagesNowhere is that more evident than in Georgia. In a state that saw nearly 5 million voters cast ballots, Joe Biden beat Trump by only 11,779 votes in 2020.

In a campaign stop in Georgia in March 2024, Trump chose to hold a rally in the small city of Rome, located in the district of one of his most die-hard supporters, Marjorie Taylor Greene, the far-right Republican U.S. representative.

In 2020, voters in the metro Atlanta area and other larger cities voted for Biden. But in more rural areas such as Rome, voters cast their ballots for Trump – and appear in polls to be giving Trump an edge over Biden in the 2024 race.

One of the major issues is U.S.-Mexico border security and Trump’s views on immigration, which critics have characterized as racist.

During the rally, Trump blamed Biden for the death of 22-year-old Georgia nursing student Laken Riley. An immigrant from Venezuela who entered the U.S. illegally has been arrested and charged with her murder.

“What Joe Biden has done on our border is a crime against humanity and the people of this nation for which he will never be forgiven,” Trump said as he promised to start the largest deportation of immigrants in American history.

Such proposed policies – and thinly veiled racist messages – play well in a political district represented by a far-right extremist.

Much like Maddox did nearly 60 years ago, Trump uses fear of other racial groups to gain support among white voters.

Racial demagoguery in the U.S. was once largely limited to Southern politicians who sometimes used their folksy, homespun charms as champions of the little guy to stoke racial and economic grievances. Though Trump is a wealthy businessman, he is able to convince working-class white voters that he is not only one of them but also a victim, too, of the “liberal elites.”

Donald Trump appears to have successfully translated this approach to the national stage.![]()

David Cason, Associate Professor in Honors, University of North Dakota

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.