UPDATED

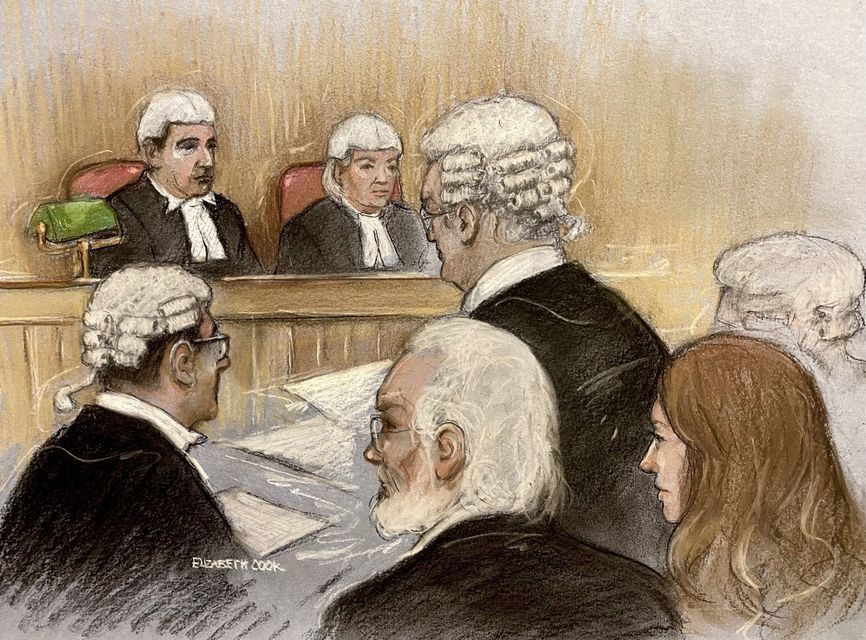

UK: Assange wins right to appeal amid renewed calls for US to drop charges

![]()

The High Court in London has granted Julian Assange the right to appeal his extradition the United States, prompting fresh hopes for his freedom.

‘ARTICLE 19 welcomes this decision and now sends a clear message to the United States: drop the charges against Julian Assange and protect press freedom,’ said Quinn McKew, Executive Director for ARTICLE 19. ‘We have repeatedly raised concerns about criminal investigations into Assange and Wikileaks, and pointed out that his extradition would criminalise journalism and have a chilling effect on freedom of expression.’

The High Court decision means the publisher and journalist is able to challenge US assurances about the conduct of a prospective trial, and about whether his right to free speech would be violated.

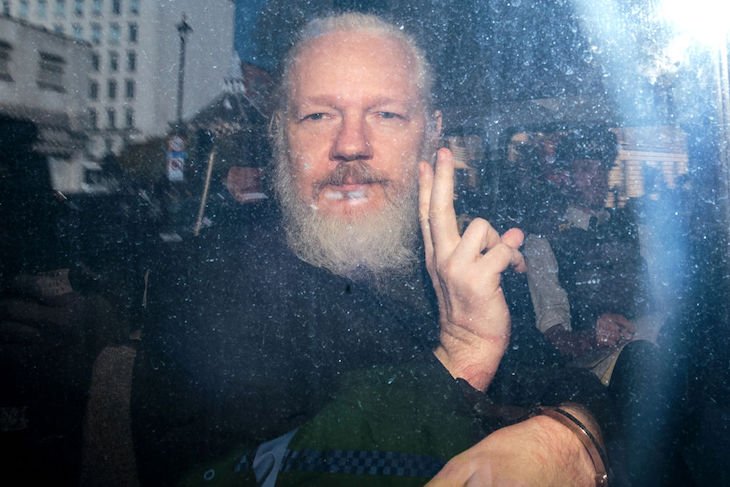

Assange faces 17 charges under the US Espionage Act for publishing more that 250,000 classified documents on the Wikileaks website in 2010, plus an additional charge on computer crimes. Assange and his legal team have argued the documents exposed evidence that the US army committed human rights violations in Afghanistan and Iraq and are protected speech under the First Amendment of the US Constitution.

WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange wins permission to challenge U.S. extradition

Jailed Australian-born Assange has been

involved in legal battles for the past 13

years

WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange was given permission to have a full appeal over his extradition to the United States after arguing at London's High Court on Monday that he might not be able to rely on his right to free speech at a trial.

Two judges at the High Court said they had given him leave to have a full appeal to hear his argument that he might be discriminated against on the basis the Australian-born Assange is a foreign national.

Hundreds of protesters had gathered outside the court ahead of what was a key ruling after 13 years of legal battles, with two judges asked to declare whether they were satisfied by U.S. assurances that Assange, 52, could rely on the First Amendment right if he is tried for spying in the U.S.

The news was met outside court by an eruption of cheering and singing. Assange's legal team had said if he lost he could be on a plane across the Atlantic within 24 hours.

His lawyer Edward Fitzgerald had told the judges they should not accept the assurance given by U.S. prosecutors that Australian-born Assange could seek to rely upon the rights and protections given under the First Amendment, as a U.S court would not be bound by this.

"We say this is a blatantly inadequate assurance," he told the court.

Fitzgerald had accepted a separate assurance that Assange would not face the death penalty, saying the U.S. had provided an "unambiguous promise not to charge any capital offence."

The U.S. said its First Amendment assurance was sufficient. James Lewis, representing the U.S. authorities, said it made clear that Assange would not be discriminated against because of his nationality in any U.S. trial or hearing.

Asaange's legal team were buoyant after the decision was made. Fitzgerald said it could be months before the appeal was heard.