Are some routes more prone to air turbulence? Will climate change make it worse? Your questions answered

A little bit of turbulence is a common experience for air travelers. Severe incidents are rare—but when they occur they can be deadly.

The recent Singapore Airlines flight SQ321 from London to Singapore shows the danger. An encounter with extreme turbulence during normal flight left one person dead from a presumed heart attack and several others badly injured. The flight diverted to land in Bangkok so the severely injured passengers could receive hospital treatment.

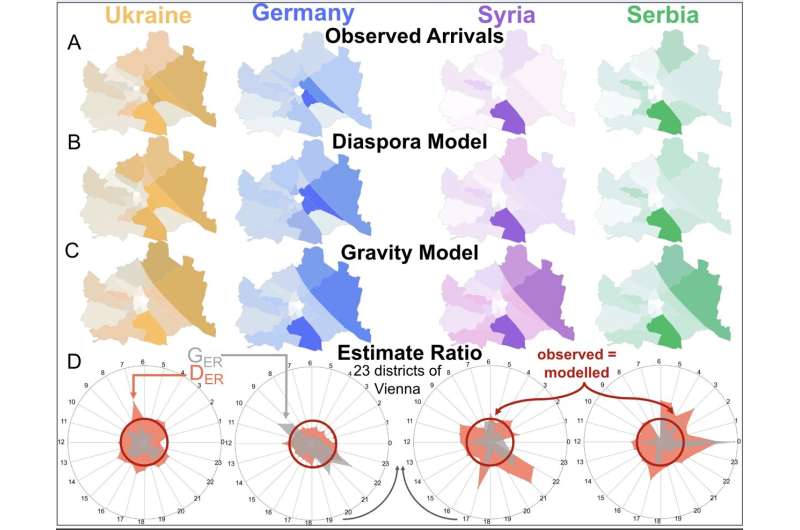

Air turbulence can happen anywhere, but is far more common on some routes than on others.

Climate change is expected to boost the chances of air turbulence, and make it more intense. In fact, some research indicates turbulence has already worsened over the past few decades.

Where does turbulence happen?

Nearly every flight experiences turbulence in one form or another.

If an aircraft is taking off or landing behind another aircraft, the wind generated by the engine and wingtips of the lead aircraft can cause "wake turbulence" for the one behind.

Close to ground level, there may be turbulence due to strong winds associated with weather patterns moving through the area near an airport. At higher altitudes, there may be wake turbulence again (if flying close to another aircraft), or turbulence due to updraughts or downdraughts from a thunderstorm.

Another kind of turbulence that occurs at higher altitudes is harder to predict or avoid. So-called "clear-air turbulence" is invisible, as the name suggests. It is often caused by warmer air rising into cooler air, and is generally expected to get worse due to climate change.

At the most basic level turbulence is the result of two or more wind events colliding and creating eddies, or swirls of disrupted airflow.

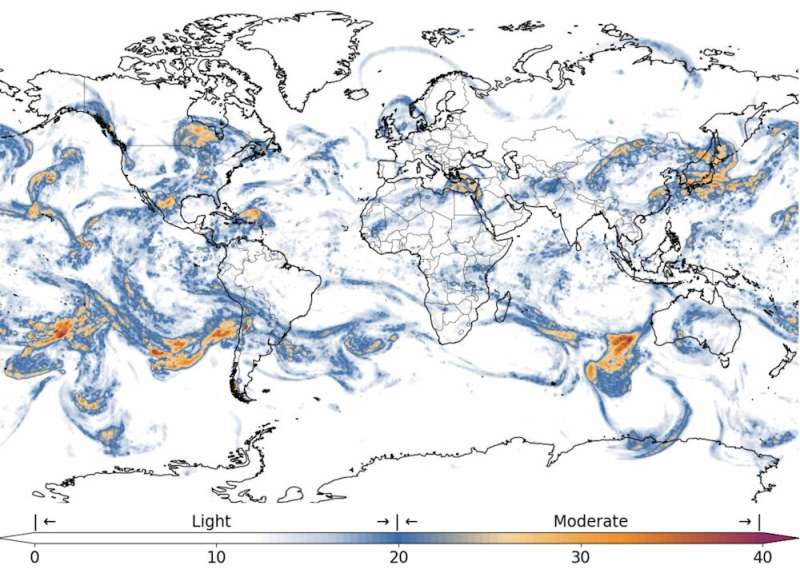

It often occurs near mountain ranges, as wind flowing over the terrain accelerates upward.

Turbulence also often occurs at the edges of the jet streams. These are narrow bands of strong, high-altitude winds circling the globe. Aircraft often travel in the jet streams to get a speed boost—but when entering or leaving the jet stream, there may be some turbulence as it crosses the boundary with the slower winds outside.

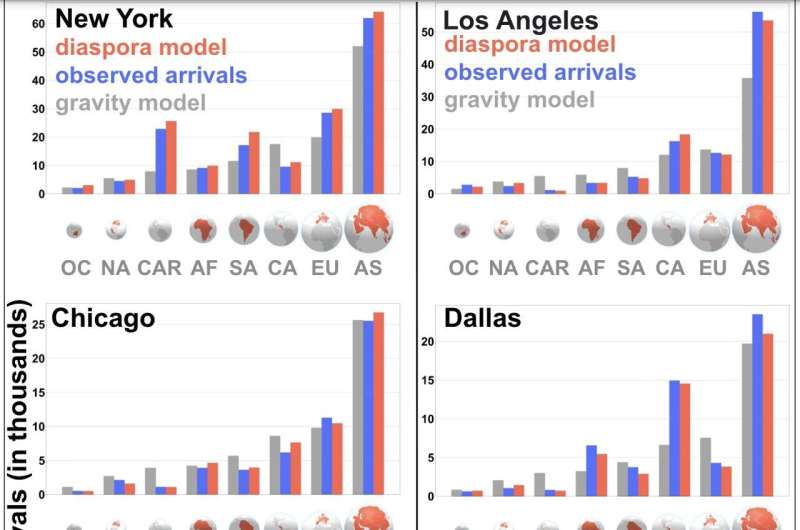

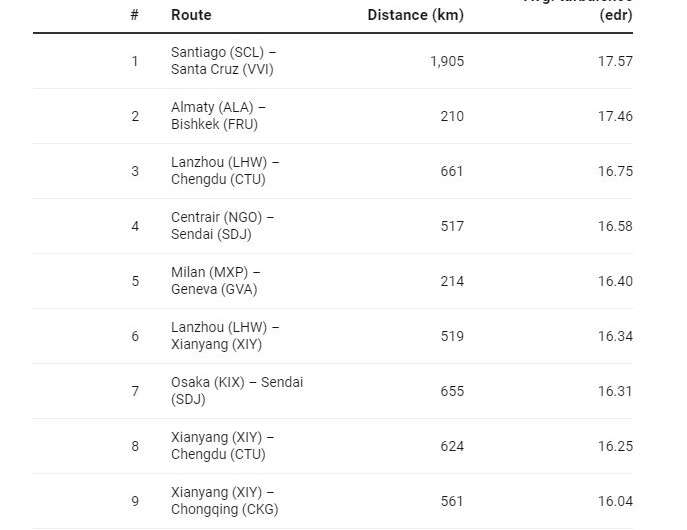

What are the most turbulent routes?

It is possible to map turbulence patterns over the whole world. Airlines use these maps to plan in advance for alternate airports or other essential contingencies.

While turbulence changes with weather conditions, some regions and routes are more prone to it than others. As you can see from the list below, the majority of the most turbulent routes travel close to mountains.

In Australia, the highest average turbulence in 2023 occurred on the Brisbane to Sydney route, followed by Melbourne to Sydney and Brisbane to Melbourne.

Climate change may increase turbulence

How will climate change affect the future of aviation?

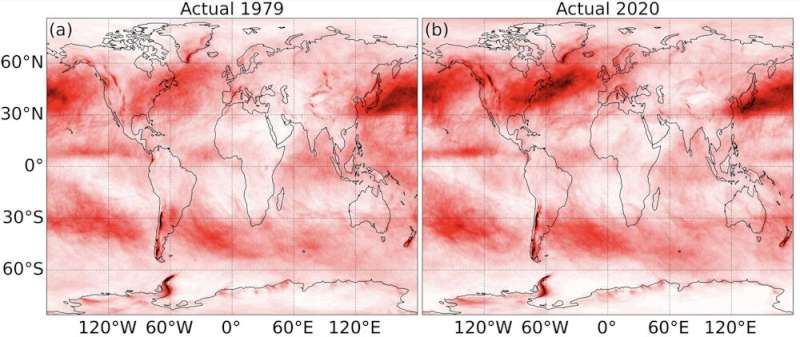

A study published last year found evidence of large increases in clear-air turbulence between 1979 and 2020. In some locations severe turbulence increased by as much as 55%.

In 2017, a different study used climate modeling to project that clear-air turbulence may be four times as common as it used to be by 2050, under some climate change scenarios.

What can be done about turbulence?

What can be done to mitigate turbulence? Technology to detect turbulence is still in the research and development phase, so pilots use the knowledge they have from weather radar to determine the best plan to avoid weather patterns with high levels of moisture directly ahead of their flight path.

Weather radar imagery shows the pilots where the most intense turbulence can be expected, and they work with air traffic control to avoid those areas. When turbulence is encountered unexpectedly, the pilots immediately turn on the "fasten seatbelt" sign and reduce engine thrust to slow down the plane. They will also be in touch with air traffic control to find better conditions either by climbing or descending to smoother air.

Ground-based meteorological centers can see weather patterns developing with the assistance of satellites. They provide this information to flight crews in real time, so the crew knows the weather to expect throughout their flight. This can also include areas of expected turbulence if storms develop along the intended flight route.

It seems we are heading into more turbulent times. Airlines will do all they can to reduce the impact on planes and passengers. But for the average traveler, the message is simple: when they tell you to fasten your seatbelt, you should listen.

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()