Connor Sheets

May 23, 2024

Private security guards with Apex Security Group and Contemporary Services Corporation patrol UCLA on May 7, following days of protests on campus. (Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

When authorities launched the first of many flash-bang-style devices early on the morning of May 2, it shattered the relative calm of UCLA’s pro-Palestinian encampment and drove a stream of protesters running toward makeshift barricades that blocked the exits.

Two students said they witnessed a student protester standing near Powell Library attempt to move a metal barrier to accommodate the people fleeing. Instead, he was met with force by members of Apex Security Group, according to the witnesses, who were interviewed together and requested anonymity in fear of retaliation by the university or law enforcement.

“Members of the security team started attacking him. I think it was around five to seven of the security guards,” one of the students said. “Two or three of them were trying to hit him on the head, and the others were trying to restrain him.”

The protester broke free from the private security guards and fled. Within minutes, a deep bruise materialized on the young man's face where one of the guards had punched him, the second student witness said. The student who was allegedly hit was not identified and could not be reached for comment.

“It was really unwarranted. He just, like, moved back a little bit and then they attacked,” the second witness said. “It was a really scary feeling. I’d never seen someone get beat up like that in person before.”

The incident was the first of at least two that witnesses said involved Apex Security Group guards acting aggressively at UCLA in recent weeks. Witnesses who spoke with The Times accused the guards of assaulting and accosting demonstrators who posed no threat and leaving the scene at a key moment on May 1, as counterprotesters escalated violence that left at least 30 people injured.

Read more: 'Shut it down!' How group chats, rumors and fear sparked a night of violence at UCLA

Apex and its parent company, the Northridge-based security giant Contemporary Services Corporation, did not respond to requests for comment. Apex's website says it employs "off-duty and retired law enforcement officers who provide supplemental services for clients that require support above and beyond standard event security and crowd management services.”

Hired guards are increasingly ubiquitous at college protests, with Apex and CSC contracted for security on campuses from Los Angeles to New York. The guards perform crowd control and many of the duties traditionally carried out by police officers, and can carry weapons if properly licensed. They can detain people, but typically as private citizens, not sworn law enforcement, which means they enjoy fewer of the legal protections afforded police. Entry-level private security guards — who in many cases receive just a few days of training — are often directed by those who hire them to use force only as a last resort.

It's unclear what instructions Apex had from UCLA.

Security guards with Apex Security Group and Contemporary Services Corporation stand by at UCLA as pro-Palestinian activists demonstrate in front of Dodd Hall on May 6. (Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

Ryan King, a spokesman for the office of the University of California's president, Michael V. Drake, said in an email that Drake announced on May 7 "an independent investigation" into what led to the violence on April 30. The university did not respond directly to questions about its relationships with Apex and CSC or the incidents with the firms on campus.

"The University awaits the findings of that investigation," King said. He added that the 10 UC campuses each have their own police departments "that have control and jurisdiction on their respective campuses and may request local law enforcement support or contract for additional security assistance as necessary. Each campus coordinates their response to conditions on the ground with their respective leadership."

Some protesters at UCLA and beyond have questioned why universities and law enforcement agencies increasingly rely on private security firms when cracking down on overwhelmingly nonviolent protests.

But contracting with security companies is “a common and reasonable practice,” according to Rick Santoro, a New Jersey-based security expert with more than 30 years of experience.

“Typically, public law enforcement agencies do not have the resources to provide security services on a long-term basis in situations such as labor actions [and] civil unrest,” he said via email. “It’s practical and necessary in many cases for colleges and universities to use private security contractors either exclusively or to supplement” police in such situations.

At UCLA, while Apex guards were accused of getting physical with some students on May 2, they were also filmed standing by the previous night as some pro-Israel protesters tore down barricades and incited violence.

The Apex guards, who appeared to have been unarmed, were brought in at the behest of former UCLA Police Chief John Thomas, who was removed from the post this week as he faced withering criticism over his handling of the protests.

University leaders had repeatedly directed Thomas to create a safety plan, three sources told the Los Angeles Times this month. He was told, the sources said, to spend whatever was necessary to maintain peace and order. Thomas developed a plan, the sources said, to deploy private security who would not be authorized to arrest anyone and who were told to contact the UCLA police if the situation on the ground escalated. Whether Apex personnel received directions to leave the scene in the event of violence remains unknown.

But a group of Apex security guards posted at the perimeter of the encampment ultimately left without intervening, according to witnesses and video from the scene. Mayhem ensued, with clashes between the opposing groups of protesters lasting until police in riot gear arrived more than two hours later.

Apex Security Group guards stand by as protesters clash on the UCLA campus the day before the pro-Palestinian encampment was dismantled. (Michael Blackshire / Los Angeles Times)

::

Allegations of physical altercations between Apex personnel and student protesters did not stop with the dismantling of the camp.

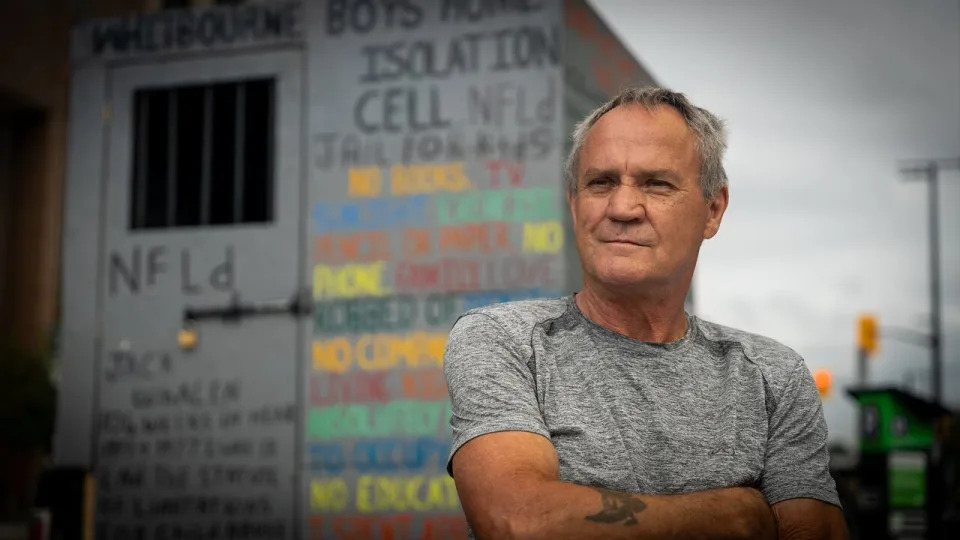

On May 15, a 2023 UCLA graduate returned to the campus to participate in a pro-Palestine demonstration. The alum, who uses the pronouns "they" and "her," said they had scrawled messages including “Free Palestine” and “How many people did you kill today?” in chalk on sidewalks and school buildings as the marchers made their way across the Westwood campus.

As the procession wound down near the university’s Shapiro Fountain, about 10 Apex guards gathered around the 5-foot-tall protester, who asked to remain anonymous, citing concerns about retaliation by law enforcement.

Three men wearing black windbreakers with APEX SECURITY GROUP emblazoned in white letters across the back and light khaki pants can be seen grabbing them by the arms in videos of the incident reviewed by The Times. Several CSC guards are visible in the background of one of the videos.

“Let them go. You’re not a f—ing cop," an onlooker yelled at one of the Apex guards. "What are you doing to them? Why are you grabbing them?”

The alum was released moments later as a guard took their tote bag and opened it up on a nearby ledge.

“Give me back my bag you f—ing pig,” they yelled as the guard rifled through the bag's contents before pulling out a red pen and holding it up in the air.

Read more: For two young journalists, showdown at UCLA camp was baptism by fire

“Come here, Miss, here’s your bag back. I have her marker that you graffitied with. Here you go,” the guard said loudly. The alum yelled back that it was a pen, not a marker. “Hold on. So she graffitied, so everybody knows. And you can’t graffiti. Here you go. Here’s your bag back.”

The alum maintained they were drawing in chalk, not making graffiti.

Apex did not respond to questions about the incident.

There have been other recent instances of protesters accusing the company of harsh tactics. In January, Apex sent dozens of guards to Berkeley, where they assisted in the clearing of tents and makeshift homes erected in People’s Park a few blocks from UC Berkeley in an attempt to block the redevelopment of the landmark site.

Columbia University used the firm as part of its controversial response to a pro-Palestinian protest movement last month.

“One security guard said the university’s contractor, Apex Security Group Inc., was recruiting more workers for its 7 p.m.-to-7 a.m. shift at a rate of $240 a day,” the New York Post reported.

The company has branches in more than a dozen cities and regularly works high-profile gigs, including Super Bowl LVIII in Las Vegas, L.A. Rams and Chargers games, and other major events.

Apex's parent company, CSC, was founded in 1967 by Damon Zumwalt, then a student athlete at UCLA. Unlike the off-duty and retired officers hired by Apex, the larger firm recruits security guards who have varying backgrounds, using a screening process that is less stringent compared with law enforcement agencies.

California requires a few dozen hours of training to become a licensed security guard. Many police departments, including the LAPD, require officers to complete a six-month stint in a police academy, followed by additional months of field training.

As a result, there's a vast pay gap between low-end private security personnel and sworn law enforcement officers. Most security guards make little more than minimum wage versus well over $100,000 a year plus government benefits for experienced cops.

It’s cheaper for a university to bring in minimally trained private security guards when needed than to hire permanent, full-time police officers, but “you get what you pay for,” according to Norman D. Bates, a security expert, attorney and founder of the Massachusetts-based security consulting firm Liability Consultants.

“The downside is lack of training, lack of experience,” he said. “The ultimate result is people are victimized, and they end up suing.”

Contemporary Services Corporation guards patrol UCLA. (Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

Law enforcement veterans like those Apex hires tend to be more calm and efficient in high-stress situations than their civilian counterparts, according to James F. Pastor, an attorney who runs a security consulting firm in Florida.

Many who contract with the company are looking for a higher level of service and capacity than a more all-purpose firm like CSC can provide. But there can be a flip side to years of experience, said Pastor, a former Chicago police officer.

“There’s a lot of good security officers out there that can manage people, that have experience in de-escalation techniques and communication techniques and just frankly using a level of professionalism to get the job done without getting too physical,” he said, but “there’s a lot of cops who lose that ability either through frustration or burnout over the years.”

Read more: Police report no serious injuries. But scenes from inside UCLA camp, protesters tell a different story

Public universities in California have paid millions to CSC in recent years. In 2023 alone, UC San Francisco paid the firm more than $3.5 million, while UCLA paid the company nearly $185,000, according to California state spending records compiled by openthebooks.com, a project of the nonprofit open government organization American Transparency.

Since 2017, according to the spending records, several other state universities and colleges have also hired CSC, while no other state agency has.

In California between 2021 and 2023, the records show, less than $330,000 of state funds were paid directly to Apex Security Group, all by Cal State East Bay and San Francisco State. It’s unclear whether payments made to CSC can cover services rendered by Apex.

King, of the UC president's office, said via email that information about how much money UCLA and other UCs have paid Apex and CSC and what contracts they have with the security firms was not "immediately available."

Even with incidents like those alleged at UCLA, private guards are here to stay at concerts, sporting events and on college campuses.

“What I see now is a driving towards private security,” Pastor said. “I think post-George Floyd, the reality is police are having a much more difficult time recruiting and keeping trained police officers. So I think that tide is turning where they’re seeing the value of having a private security officer next to them.”