Remember they said Miami would be under water? Here’s a preview of our future

the Miami Herald Editorial Board

Wed, June 12, 2024

It’s like an unspoken social contract. When people choose to live in South Florida, they must make peace with the possibility that, thanks to hurricanes, there will be flooding and they may incur thousands of dollars to fix their homes post storm.

But that’s supposed to be during a major storm with a name — like Irma, Ian or Andrew — not any given day during heavy rains as it happened Wednesday in Miami-Dade and Broward counties.

Flooding was so intense that part of Interstate 95 was shut down in Broward as water pooled on the highway. Roads were rendered impassible in places like Hollywood and Miami Beach. A rare flash flood emergency was issued.

Last April — even before the 2023 hurricane season started — historic flooding in Fort Lauderdale caught residents and officials by surprise. The city had to use airboats to rescue people from their homes and, on the following day, abandoned cars caught in the water lined the streets of the city’s downtown.

When we hear about the threat of flooding and sea-level rise caused by climate change, that may appear like a distant future. It’s not — and this week’s torrential rainfall proves South Florida is not fully ready for increased water levels despite local governments and the state having spent millions of dollars to keep streets dry. Anyone driving in Downtown Miami on a rainy day can see how quickly streets flood.

Victor Corone, 66, pushes his wife Maria Diaz, 64, in a wheelchair through more than a foot of flood water on 84th street in Miami Beach on Wednesday, June 12, 2024.

This is a new reality. With hurricanes, residents have time to prepare. This week, many were caught off guard. Although flood warnings had been in place for days in parts of the region, weather forecasters alerted us too late about the worst outcomes of the storm. In the future, they may have to develop new types of warnings to convey the severity of what’s to come.

The pace of sea-level rise has picked up in recent years. The financial consequences are enormous for local governments as well as residents as the cost to insure homes and vehicles rise.

Local sea level has risen about a foot in the last 80 years, with 8 inches of that total in the last 30 years, the Herald reported in May. The second foot will take only 30 years; the next foot, 20 years, according to estimates by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The average elevation in Miami is only 3 feet.

Besides the impacts of climate change, warmer ocean waters and the melting of ice sheets, the Florida Current — an offshoot of the Gulf Stream, a massive current that runs from the tropics to the Arctic — can also impact water levels in Miami, the Herald reported. And parts of the region’s land is sinking, though not by much, in a process known as subsidence.

The real answer to South Florida’s predicament is to slow down the burning of fossil fuels that cause climate change, according to a consensus by most scientists. The scientific community has warned that the Earth’s temperature is rising to dangerous levels.

Beyond tackling climate change on a global scale, our local and state officials will have to pick up the pace in preparing South Florida for the worst. In the city of Miami, for example, voters approved a 2018 bond referendum to finance sea-level rise mitigation but a constant complaint is that projects aren’t coming online quickly enough.

Florida has taken unprecedented steps to allocate dollars to help communities fund such projects. Gov. Ron DeSantis appointed a resilience officer to prepare Florida for the environmental and economic impacts of rising sea waters. Yet, this year, DeSantis signed a bill that lowered the standards for sea-rise projects eligible for state funding. He also signed another bill that removes references to “climate change” from Florida law.

Public works projects can take years to come to fruition. This week showed that residents and businesses have to be mentally and physically prepared for flooding that we once thought we could anticipate as we tracked hurricane spaghetti models.

A Miami underwater is becoming a reality we’ll have to accept.

Record rainfall wreaks havoc in South Florida with "life threatening" flooding, stalled cars, delayed flights

Kimberly Miller, Palm Beach Post

Thu, June 13, 2024

An aspiring early-season tropical cyclone ambushed Florida in a blitzkrieg of rain this week that shut down portions of Interstate 95 on Wednesday, waylaid flights and triggered “life threatening flooding” on roadways throughout Broward and Miami-Dade counties.

By 4 p.m. the National Weather Service in Miami said numerous and “non-stop” reports of flooding were coming in after it had issued seven flash flood warnings across its forecast region throughout the day.

Hourly rainfall rates on one afternoon thunderstorm were predicted to be 5 to 6.5 inches per hour.

“Want to be clear here,” said NWS Miami meteorologist Sammy Hadi in an online alert. “This storm has very, very heavy rainfall. This will only exacerbate the ongoing flash flooding.”

The heavy rainfall had been forecast early in the week, but the drubbing that first hit the southwest coast on Tuesday and then the tri-county area of Palm Beach, Broward and Miami-Dade on Wednesday was record-breaking.

As of 4:30 p.m., 6.77 inches of rain was recorded at Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport, dashing the record of 5.47 inches recorded in 1978. Palm Beach International Airport in West Palm Beach recorded 2.38 inches of rain, which fell far short of the 1901 record of 9.71 inches. About 2.25 inches of rain was measured at Miami International Airport on Wednesday, which is also far from the record 8.25 inches also measured in 1901.

A cyclist rides through the rain along Flagler Drive on June 12, 2024, West Palm Beach, Florida.

“The tropical spigot pouring into South Florida has unleashed some of the soupiest air measured for our area in June, historically South Florida’s rainiest month,” said Michael Lowry, a meteorologist with South Florida ABC affiliate Channel 10 in his Eye on the Tropics column. “With such a juiced atmosphere overhead, otherwise innocuous disturbances moving along in the atmosphere can bring lots of rain in little time.”

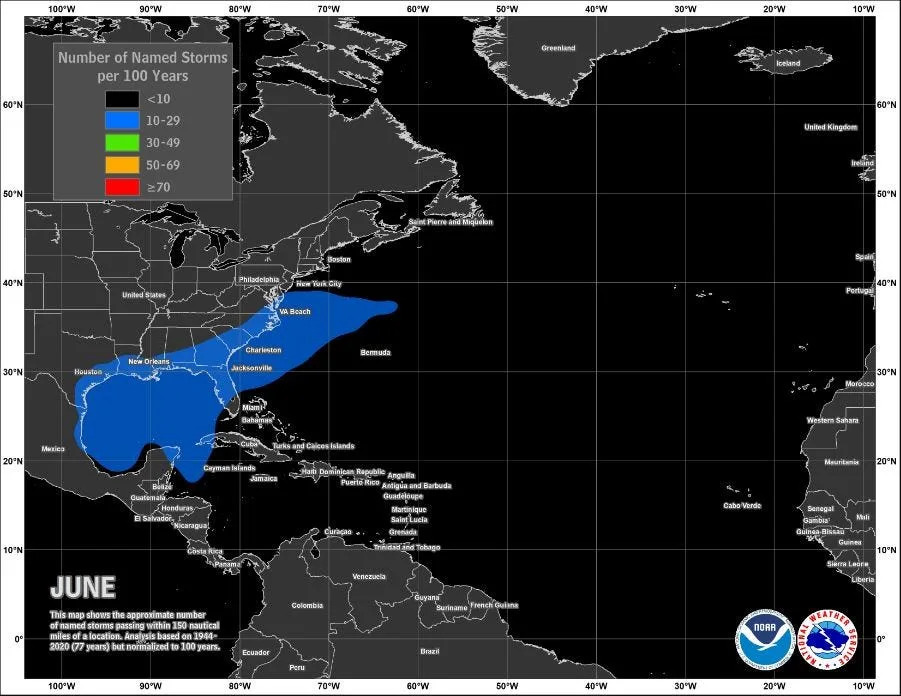

Early-season tropical cyclones find a fertile nursery in the rich waters of the Gulf of Mexico and western Caribbean Sea where stalled cool fronts can goad them to maturity in June and July.

The National Hurricane Center noted two areas to watch this week in the Gulf of Mexico with one, dubbed Invest 90-L, dumping days of flooding rainfall on Florida as it makes its way to the Atlantic Ocean and the other looking to find purchase in the Bay of Campeche.

The NHC gave 90-L, a disorderly mish-mash of showers and thunderstorms, a 20% chance of development over the next seven days. But that mattered little to areas such as Sarasota where 11 inches of rain fell through early Wednesday, or to drivers on I-95, which was shut down Wednesday afternoon in Broward County because of flooding.

FHP Lt. Indiana Miranda said at about 3 p.m. that traffic was being diverted at Oakland Park Boulevard and that a contractor was working to pump water off the roadway.

"We have one vehicle flooding in the area," Miranda said in an email. "This closure will remain until further notice and water drains from the Interstate."

Climatologically, homegrown tropical systems in the Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico and southwestern Atlantic are more common in the early days of the hurricane season ahead of the main-event months of August, September and October when waves rolling off Africa can swell to Goliaths in their trek west.

Early season tropical cyclones often from in the Gulf of Mexico and off the southeast coast of the U.S.

“This early in the season there is usually too much Saharan dust and too much shear in the Atlantic for those storms to form so it’s rare to see something there this early on,” said AccuWeather lead hurricane forecaster Alex DaSilva about the region between Africa and the Caribbean. “This time of year, you look closer to home.”

Saharan dust, made up of sand and mineral particles swept up from 3.5 million square miles of desert, spoils tropical development by stealing moisture from the air needed for storms to form.

But in the Gulf of Mexico, an ample feed of gooey air is usually available. That moisture, combined with a stalled boundary over north Florida where winds converged and pressure lowered, gave Invest 90-L life.

Most areas of Palm Beach County got only 2 to 4 inches Tuesday but experienced prolonged showers Wednesday with some areas forecast to get more than 5 inches. Thunderstorms were strong enough to trigger a tornado warning for Wellington, Loxahatchee Groves, Palm Beach Gardens and Royal Palm Beach. And a flood watch was extended through 8 p.m. Friday.

Hurricane season 2024: More than 1 million new Florida residents may not understand storm prep

A man dashes for cover from the rain during a downpour on June 12, 2024, West Palm Beach, Florida.

By Wednesday afternoon, the National Weather Service in Miami said "life threatening" flooding was occurring in Broward and Miami-Dade counties.

Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport had massive cancellations, delays and flight diversions Wednesday because of the rain. It occurred a little over a year after major flooding shut down the airport and closed schools in and around Fort Lauderdale. During that April 12, 2023 drenching, the area saw about 26 inches of rain in a 24-hour period.

On Wednesday, airport officials warned on social media that flooding at entrances and exits was slowing traffic.

The tropical moisture will remain “entrenched” over South Florida through the remainder of the week with conditions favorable for flooding and flash flooding, especially in poorly draining urban areas.

The average first-named storm of the hurricane season doesn’t occur until June 20.

All forecasts point to trouble: Forecasts all point to a busy season with La Niña and warm ocean temps

Weather.com senior meteorologist Jonathan Erdman said he’s more bullish about something forming next week in the area in the southwestern Gulf of Mexico highlighted by the NHC on Wednesday.

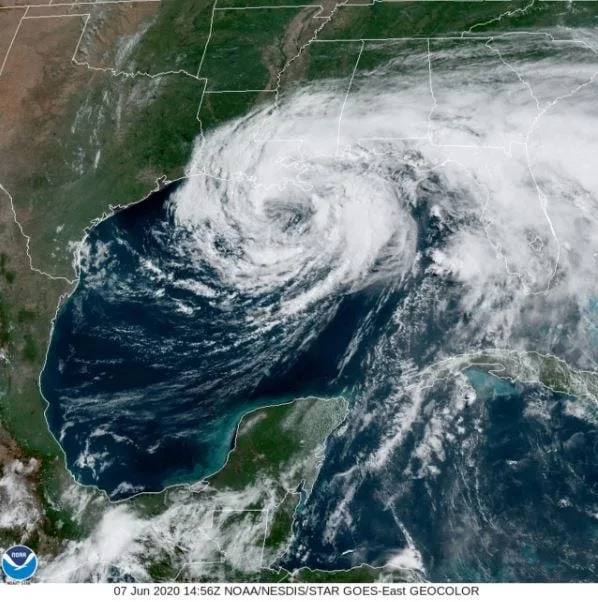

Tropical Storm Cristobal on June 7, 2020. Cristobal formed from the Central American gyre. It made landfall in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana bringing more than a foot of rain to areas of southeastern Louisiana, southern Mississippi, and North Florida.

It’s possible if something forms it would be a piece of the Central American Gyre, which is responsible for several past tropical cyclones including Tropical Storm Cristobal in 2020, Hurricane Michael in 2018 and Hurricane Ida in 2009.

Erdman is already looking to the main development region.

“We are seeing pretty beefy-looking tropical waves out there already, and that is an ominous sign for a more active season,” he said. “Once the wind shear in that area relaxes and the Saharan air pushes away, the door is open.”

Kimberly Miller is a journalist for The Palm Beach Post, part of the USA Today Network of Florida. She covers real estate and how growth affects South Florida's environment. Subscribe to The Dirt for a weekly real estate roundup. If you have news tips, please send them to kmiller@pbpost.com. Help support our local journalism, subscribe today.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: Showers deluge areas of South Florida with bouts of flooding rain