Dmitry Pozhidaev

13 June, 2024

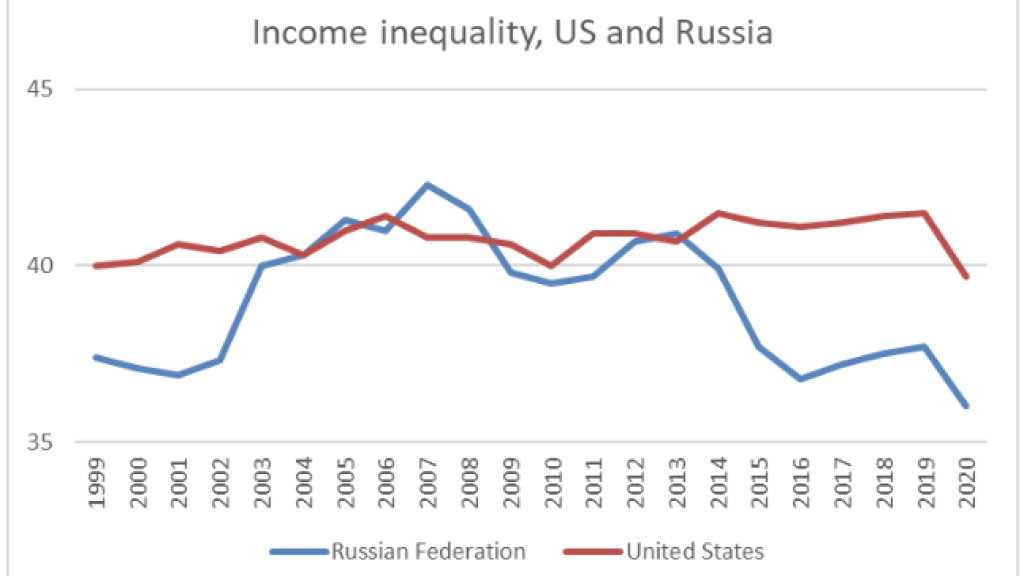

Russia is becoming more equal, at least as far as the income inequality is concerned. To remember, during and after its transition to the market economy in the 1990s, Russia scored the dubious record of being one of the most unequal countries in the world, second to only to South Africa and on par with (or sometimes even ahead of) the US. Yet, Russia started diverging from the US around 2014, steadily reducing its inequality measured by the Gini coefficient.

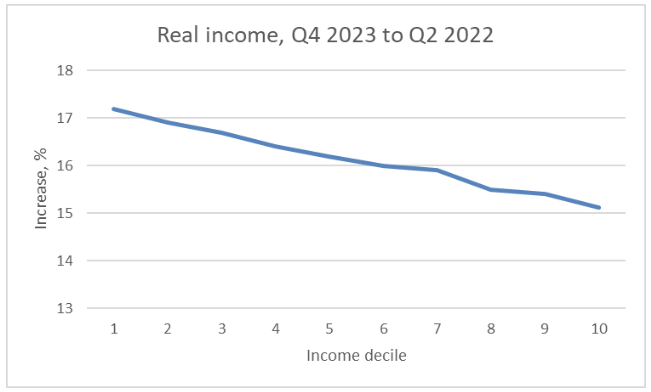

This trend has accelerated since 2022, the real incomes of the poor deciles growing faster than those of the rich deciles. In fact, real incomes grew inversely to the position of the income decile: the poor the decile, the higher its income growth. Analyzing this trend, Ekaterina Kurbangaleeva of the Carnegie Foundation writes that among those who are “winning” from the current situation are the millions of Russians in blue-collar and gray-collar jobs whose professions were long considered low paid and low status.

It is difficult not to notice that this income equalization trend coincides with the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, the start of the full-blown war in Ukraine in February 2022, and the introduction of massive Western sanctions. So, what has been causing this drive to greater income equality in Russia?

War Keynesianism

The most frequent explanation among mainstream economists is the transition to a war economy (also known as war Keynesianism), which started in Russia around 2014. Surely, the sanctions (or the threat of sanctions) did play a role and hastened this transition, but this is not the whole story. The traditional story of war Keynesianism goes like this. During wartime, governments often implement significant fiscal and monetary measures to mobilize resources, fund military operations, and maintain economic stability. Increased government spending and mobilization of resources often lead to higher employment and wages, particularly for lower-income groups. The US during World War 2 is a textbook example: Wartime spending and mobilization led to significant economic growth and a reduction in income inequality. The period saw increased wages for many workers and a narrowing of the income gap.

These developments are well documented and analyzed in the recent CEPR brief “Russian economy on war footing: A new reality financed by commodity exports” authored by Yuriy Gorodnichenko, Iikka Korhonen and Elina Ribakova. The study notes increased public procurement in the regions with large concentrations of machine-building industries; an increase in transport infrastructure investment in some poor regions in Russia’s Far East, as Russia tries to redirect its foreign trade more towards China; a rise in bank deposits in the poorer regions, which have sent proportionally more people to the military; and an increase in real salaries, first in sectors receiving state orders and then in other sectors as they have struggled to attract workers.

But the question that is not adequately addressed is not why the poor are getting more (this is somewhat obvious) but why and how the rich are getting less. Why all of a sudden has the Russian growth turned pro-poor?

Russia’s delinking from the capitalist center

Viewed from the Marxist perspective, the Russian war economy represents a clear case of a peripheral country delinking from the center. Whereas the Western sanctions are usually hailed as a (relatively) effective mechanism to isolate Russia from the world economy, their other side is not discussed as much. Decoupling Russia from the capitalist center (represented by the “collective West”) also implies decoupling the West from Russia. The Marxist economist Samir Amin writing 50 years ago stressed that a break with the world market is the primary condition for development. Developing the periphery requires setting up self-centered national structures that break with the world market. More recently, the Russian Marxist Boris Kagarlitsky argued the same point in the context of Russian history after 1917: its meteoric rise in the 1920-30s was due to its decoupling from the world markets and its gradual decline from the 1970s onwards due to its reintegration in the world economy.

The relations between the center of the system and its periphery are relations of domination, unequal relations, expressed in a transfer of value from the periphery to the center. This transfer of value, governed by the fundamental law of capital accumulation under capitalism, makes possible a larger improvement in the reward of labor at the center and reduces, in the periphery, not only the reward of labor but also the profit margin of local capital. The main channel of this transfer is unequal exchange when higher values produced in the periphery (as determined by the socially necessary amount of labor) are exchanged for lower values produced in the center.

There are three main channels of surplus transfer (including surplus value and nonproductive incomes and state revenues). This channel operates, firstly, through a system of the international division of labor and foreign trade rigged by the center to ensure maximum surplus transfer. The center keeps the periphery further from the technology frontier, causing the periphery to engage in production with low value addition (often raw materials, such as minerals), in relation to which the center usually exercises monopsonistic power. At the same time, in collusion with the comprador bourgeoisie, the center keeps the rewards of the peripheral labor below its productivity, which allows higher rates of profit for foreign capital as well as part of the domestic bourgeoisie. Secondly, in addition to transfers via unfavorable (for peripheral countries) terms of trade, the center transfers the surplus produced in the periphery via profit repatriation and purchases of advanced technologies in the metropole to continue its extractive economic activities in the periphery. This is helped by the purchase of economic values below their value in the course of privatization in the periphery. Third, because foreign capital takes the commanding heights in the periphery, domestic capital does not find enough economic application in the home country, resulting in significant outflows of capital to the center where it is invested. The last channel of value extraction is the international financial system, which is rigged against the periphery. The center uses cheap credit at home to extend expensive loans to the private and public sectors in the periphery. The cost of these loans is above the normal risk premium, incorporates the higher rates of labor exploitation, and results in a debilitating loan service burden for developing countries.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russia became a textbook case of a peripheral country. It demonstrated the explicit characteristics of dependence one by one: current account deficit, deindustrialization, almost total dependence on Western exports (not only luxuries and technological goods but also foodstuff and basic necessities), foreign investments (mostly in extractive industries), massive outflows of domestic capital to foreign jurisdictions, high private and public indebtedness, and ultimately a decrease in the labor share of national income and pauperization of the working class.

Living standards started improving in the early 2000s. This improvement, which laid the foundation of Vladimir Putin’s legitimacy is believed to be largely due to two factors: (1) increased world prices of oil and gas (which jumped from $17 per barrel in 1999 to $50 in 2005 and $109 in 2012) and (2) improved political stability, economic reforms and better security conducive to increased economic activity. The latter development also included a transition from laissez-faire crony capitalism to a more tightly controlled state capitalism as will be discussed below. Yet, Russia’s structural dependence on the West continued without much change.

How has the situation changed after 2014, particularly since February 2022? As a result of Russia’s disconnection from international financial markets in 2022, the flow of foreign loans has dried up. But consequently, as reported by the Russian Central Bank, Russia’s external debt (on a decreasing path since 2014) decreased in 2023 even further by 17.7%, since the end of 2022. Indebtedness of general government to non-residents decreased by 29.1% as a result of the decrease in debt on sovereign debt securities denominated in both Russian rubles and foreign currency.

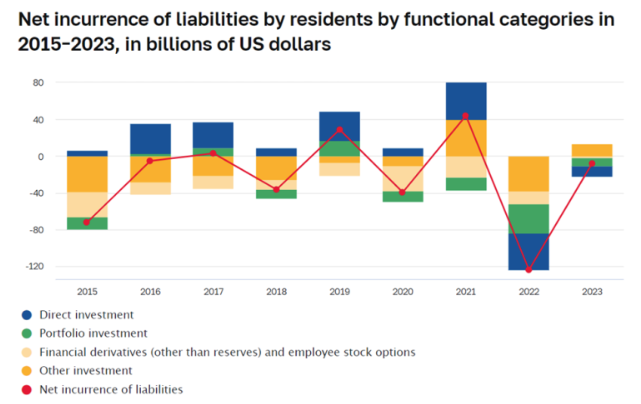

As foreign companies started closing their operations and withdrawing from Russia with the start of the war in Ukraine, profit repatriations reduced significantly. In 2023, according to the Russian Central Bank, the negative balance on investment income has halved: both income accrued in favor of non-residents and income received by residents from foreign investments have decreased. The largest role was played by the negative balance of income on direct investment, including as a result of a reduction in the degree of participation of direct investment investors in domestic business, as well as a reduction in the amounts of dividends declared by Russian companies. Net incurrence of liabilities by residents, after experiencing a negative shock in 2022, in 2023 shrank to the lowest level since 2015.

Delinked from the international capital markets and subject to international sanctions and expropriations, Russian capitalists started repatriating their foreign investments. In addition, the volume of cross-border transfers from Russia in 2023 decreased by 35% compared to the previous year. According to recent research by Frank RG, 2023 saw approximately $35 billion of “new money” returned and retained in the economy. For comparison, $35 billion is as much as the net profit of the entire banking sector last year. And that’s double the projected federal budget deficit for 2023.

According to the Central Bank, the amount of rubles held in Russian bank accounts climbed 19.7 percent to 7.4 trillion in 2023 (nearly three times what it was in 2022), buoyed by high interest rates. In particular, there has been growth in the category of deposits worth between 3 million and 10 million rubles (both in terms of their total value and in the number of people holding such deposits).

All these developments minimize surplus transfer to the center and result in higher capital accumulation inside Russia. But it does not automatically imply an improvement in the lot of the poor and less inequality: capitalists may horde the new money or use it for luxury consumption. Yet, Russian capitalism is subject to the same law of accumulation as global capitalism in general. With the closure of investment outlets abroad and the uncertainty about domestic monetary trends (growing inflation), Russian capitalists are encouraged to invest in the domestic economy. The new investment opportunities are the result of two developments: the departure of foreign capital, which reduces the competition, and increased military contracts, which include not only military hardware but also all kinds of essentially non-military equipment used by the military.

Transition to state capitalism

This notwithstanding, capitalists theoretically could still appropriate the same (or even greater) amount of surplus value (although the latter is obviously difficult in a very tight labor market). Here comes the other trend, briefly mentioned above, the transition to state capitalism, which offsets this possible behavior. As is known, one of the defining characteristics of state capitalism is a high share of state-owned enterprises. Since Putin flagged the return of strategic enterprises to state control as a priority for prosecutors in January 2023, the number of re-nationalizations has already ticked into double digits. According to the Russian Prosecutor General, in the military-industrial complex alone, 15 strategic enterprises with a total value of over 333 billion rubles (about $4 billion) have been returned to the state by March 2024. In several cases, these re-nationalizations involved assets privatized over 30 years ago. Old safeguards, like Western sanctions or friends in high places, no longer work.

These court-mandated asset seizures are not isolated cases, but part of a broader strategy impacting the oil and gas sector, infrastructure facilities, enterprises related to the military-industrial complex, the chemical industry, and agriculture. But even when enterprises continue to function as nominally private, the status of their owners has changed as a result of “soft” re-privatization. In such cases senior management of companies are removed and replaced by a new generation of Putin allies without the use of courts – de-privatizing the organizations in all but name. As Chatham House’s expert Nikolai Petrov argues, oligarchs and other members of the economic elite are being reduced to roles equivalent to that of “red directors” during the Soviet Union – that is, managers rather than owners of property, and without independent political power. These “directors” have but a limited claim on the profits of enterprises under their management, and their personal consumption is monitored and controlled much more tightly than during the age of laissez-faire capitalism.

True, Russia’s foreign trade is still based on the export of hydrocarbons (a large share of which is still destined for the Western core via intermediaries, such as India and Turkey). Russia’s pivot to China is much discussed and often derided as a new vassal dependence. Yet, being part of the periphery itself, China may look favorably at Russian attempts at self-centered development in areas other than extractive industries. Indeed, Russia has technologies, experiences and information that China may value. China, through initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), could offer alternative sources of finance and investment. Russia’s pivot does not mean switching one dominant center (the West) for another (China). As Mikhail Korostikov of the Carnegie Foundation argues, the relationship between Russia and China is by no means perfect, but the shared interests of both countries’ leaderships and the strategic logic of the confrontation with the West create a solid foundation for reasonably equal cooperation.

State capitalism does not automatically imply pro-poor development. But in the case of Russia, it is coupled with de-linking from the center, which offers more opportunities for capital accumulation. At the same time, the surplus accrued to capitalists decreases and the surplus available to the state increases through “hard” and “soft” re-nationalization. State capitalism is not inherently superior to market capitalism when it comes to the allocation of resources or income redistribution. But it does have a better potential to mobilize and direct resources to a limited number of objectives in a crisis situation (to serve as a mission-oriented government, to borrow Marianna Mazzucato’s term). This is what happens now in Russia as the country mobilizes more and more for the achievement of its war objectives.

The new tax reform announced by Putin envisages a progressive personal income tax scale to replace the flat 13% PIT tax. The tax rate will increase from 15 to 22 percent depending on the income. The reform is expected to bring the state an additional 16.8 trillion rubles (about $190 billion) in the next 6 years. During the same period, the state intends to collect another 11.1 trillion rubles (approximately $125 billion) from the business as the corporate income tax will increase from 20% to 25%. The Russian Left insisted on these changes for many years. Ironically, it has happened now, triggered by the war. Be as it may, until now Russia remained the only G20 country with a flat income tax rate. This reform would have been hailed as an important step to greater income equality if it had happened in any other country and under different circumstances. Whereas the immediate objective of the reform is to increase the fiscal space for the war effort, it will also contribute to better equality between the regions and different income groups as the current trend indicates.

At the same time, the current level of Russian economy’s militarization remains limited. According to the US Central Intelligence Agency, the military burden on the Soviet economy, reckoned as a share of GNP, rose from 12 percent in 1970 to 18 percent in 1980 and probably reached 21 percent by the end of its existence. The Swedish Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) estimates Russia’s total military expenditure in 2024 at 7.1 percent of GDP in 2024 (for comparison, it was 5.4 percent in 2015). It is nowhere near the Soviet level and the Russian economy is more resilient and less dependent than the Soviet economy. Russia’s delinking from the imperialist center plays an important role in strengthening this resilience due to increased capital accumulation and decreased value transfer. Hence, Russia has the potential to run this kind of military Keynesianism for many years in a symbiotic relationship with state capitalism. Keynes himself wrote about his General Theory that the book’s argument was “much more easily adapted to the conditions of a totalitarian state” than to a democracy. Hence, Russia has the potential to run this kind of military Keynesianism for many years in a symbiotic relationship with state capitalism. Keynes himself wrote about his General Theory that the book’s argument was “much more easily adapted to the conditions of a totalitarian state” than to a democracy.

Uncertain future

But this future is not without a challenge in the long run. While state capitalism facilitates and enables the war economy, Marxists argue that military expenditures only temporarily boost capital accumulation through demand creation. Military spending can exacerbate the contradictions within capitalism by increasing the state’s role in the economy without addressing underlying issues of surplus value extraction and capital accumulation. Janos Kornai argued many years ago that state intervention “softens” budget constraints. As a result, unproductive activities can persist because there is external support to cover deficits. These activities do not necessarily add real value to the economy. In addition, Moscow needs crude prices to stay around the current $90 a barrel; a slump to, say, $60 could make things difficult. Ultimately, the possibility of a significant military escalation with the West is looming larger than life and can totally change the calculus. The future is uncertain: as we have observed, the redlines are set and crossed again and again in this war.

One thing is known: we don’t really know what will happen in the long run, except that we’re all dead, as Keynes quipped (and this may happen even sooner than we think in case of a sharp escalation leading to the use of nuclear weapons). One can reasonably suggest however that the situation of decoupling and reorientation will persist, at least in the medium run. Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov recently said that there would be no cooperation with the West for at least one generation. In economics, the exact time span for a generation can vary, but it is often considered to be around 20 to 30 years.

Dmitry Pozhidaev has spent the past 25 years as a development practitioner in the Balkans, former Soviet Union, Africa and Asia. He blogs at Elusive Development.