Decolonization is always a violent event.

– Frantz Fanon

From Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth, I substituted Palestine and Palestinians for “colonized” and Israel and Israelis for “colonizers.”

For the Palestinians, to be a moralist quite plainly means silencing the arrogance of the Israelis, breaking (their) spiral of violence, in a word ejecting them from the picture. (page 9)

The Israelis are no longer interested in staying on and coexisting once the colonial context has disappeared. (page 9) (Me: it’s already happening as thousands of Israelis in the past nine months have gone back to their ancient homelands of Rockaway and Woodland Hills.)

Israel only loosens its hold when the knife is at its throat. Israel’s naked violence only gives in when confronted with greater violence. (page 23) (Me: actually it doesn’t take nearly as much as Hezbollah helped Israel discover in 2006.)

Palestinians have had it constantly drummed into them that the only language they understood was that of force, now they decide to express themselves with force. In fact the Israelis have always shown them the path they should follow to liberation. (page 42)

Palestinians register the enormous gaps left in their ranks as a kind of necessary evil. Since they have decided to respond with violence, they admit the consequences. (page 50)

The work of the Israelis is to make even dreams of liberty impossible for the Palestinians. The work of Palestinians is to imagine every possible method for annihilating the Israelis. (page 50) (Me: actually years ago Hamas accepted a “hudna,” a long-term truce based on the 1967 borders.)

(Me: actually Palestinians are much better people than Israelis.)

Violence is a cleansing force. It rids Palestinians of their inferiority complex, of their passive and despairing attitude. It emboldens them, and restores their self-confidence. (page 51) (Me: Palestinians’ 2018-2019 Gandhian non-violent Great March of Return was met with Israeli snipers killing 223 and injuring over 9,000 others.)

Violence is a cleansing force. It rids Palestinians of their inferiority complex, of their passive and despairing attitude. It emboldens them, and restores their self-confidence. (page 51) (Me: Palestinians’ 2018-2019 Gandhian non-violent Great March of Return was met with Israeli snipers killing 223 and injuring over 9,000 others.)

Whatever gains the Palestinians make through armed or political struggle, they are not the result of Israel’s good will or goodness of heart but to the fact that it can no longer postpone such concessions. (page 92)

Toward the end of The Wretched of Earth, Fanon details the diabolical tortures inflicted on Algerians (many by doctors, of course) and elaborate brainwashing techniques utilized by the French. For this paragraph on brainwashing, there’s no need to even substitute Palestine and Palestinians for Algeria and Algerians:

Algeria is not a nation, has never been a nation, and never will be. There is no such thing as the ‘Algerian people.’ Algerian patriotism is devoid of meaning. (page 214)

The world must unite to defeat Israel. The openly ethno-supremacist and genocidal actions and comments by Israel and its supporters are what happens when Israeli war crimes and human rights violations are allowed to fester for over seven decades. Israel is as if the Nazis were allowed to survive and continue their genocidal ways. Israel must be delivered its Stalingrad.

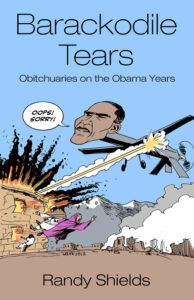

Randy Shields just released second book is Barackodile Tears: Obitchuaries on the Obama Years. He is also the author of Some Fantastic Place: Essays on Non-humans and Yahoomans. He can be reached at music2hi4thehumanear@gmail.com. Read other articles by Randy, or visit Randy's website.

It’s an increasingly familiar contradiction: digital platforms that position themselves as an accessible alternative to corporate media emerge as new censors in their own right. Social media and the internet make it possible to disseminate material that would otherwise have been suppressed, thereby helping to bring alternative conversations to the fore of mainstream awareness. And yet, for all of their hype and propaganda, the parent companies of these popular digital platforms are no less dedicated to the preservation of an imperialist status quo than their institutional predecessors, with all of the attendant silencing and repression this entails.

Big Tech’s handling of content critical of the Zionist state’s latest genocide of Palestinians in Gaza—described by former United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) spokesman Chris Gunnes as “the first genocide in the history of humanity that is livestreamed on television”—reveals that silencing is the norm. In this way, Big Tech companies reinforce Israeli settler colonialism through systemic anti-Palestinian policies. I analyze the meeting point between Big Tech and Zionist oppression of Palestinians as digital/settler-colonialism.

An Egregious Culprit

Facebook acquired Instagram on April 9, 2012, and rebranded itself as Meta on October 28, 2021. In addition to these other changes, the company has consistently worked to facilitate the censoring and repression of Palestinians on its platforms—often with deadly consequences. Israel relies on membership in WhatsApp groups as one of the data points for Lavender, the AI system it uses to generate “kill lists” of Palestinians in Gaza. Israeli Occupation Forces (IOF) are not required to verify the accuracy of the “suspects” generated by the AI program, and make a point of bombing them when they are at home with their families. Another AI program, insidiously named “Where’s Daddy?,” helps the IOF track Palestinians targeted for assassination to see when they’re at home. As blogger, software engineer, and Tech for Palestine co-founder Paul Biggar notes, the fact that WhatsApp appears to be providing the IOF with metadata about its users’ groups means that Meta, the parent company of the messaging app, is not only lying about its promise of security but facilitating genocide.

This complicity in genocide has also assumed other, sometimes more subtle guises, including systematic erasure of support for Palestine from Meta’s platforms. On Tuesday, June 4, 2024, Ferras Hamad, a Palestinian American software engineer, launched a lawsuit against Meta when the company fired him after he used his expertise to investigate whether it was censoring Palestinian content creators. Among Hamad’s discoveries was that Instagram (owned by Meta) prevented the account of Motaz Azaiza, a popular Palestinian photojournalist from Gaza, from being recommended based on a false categorization of a video showing the leveling of a building in Gaza as pornography. Improper flagging based on automation is one of the key mechanisms by which pro-Palestine content is systematically removed from Meta’s platforms.

On February 8, 2024, The Intercept reported that Meta was considering a policy change that would have disastrous implications for digital advocacy for Palestine: identifying the term “Zionist” as a proxy for “Jew/Jewish” for content moderation purposes, a move that would effectively ban anti-Zionist speech on its platforms, Instagram and Facebook.

The revelation came as a result of a January 30 email Meta sent to civil society organizations soliciting feedback. This email was subsequently shared with The Intercept. Sam Biddle, the reporter of The Intercept piece, notes that the email said Meta was reconsidering its policy “in light of content that users and stakeholders have recently reported,” but it did not share the stakeholders’ identities or give direct examples of the content in question. Seventy-three civil society organizations, including Jewish Voice for Peace, 7amleh, MPower Change, and Palestine Legal, issued an open letter to Meta founder Mark Zuckerberg to protest the potential policy change.

“[T]his move will prohibit Palestinians from sharing their daily experiences and histories with the world, be it a photo of the keys to their grandparent’s house lost when attacked by Zionist militias in 1948, or documentation and evidence of genocidal acts in Gaza over the past few months, authorized by the Israeli Cabinet,” the letter states.

If this sounds familiar, it should. In 2020, Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP) launched a global campaign entitled “Facebook, we need to talk” with thirty other organizations to pressure Meta not to categorize critical use of the term “Zionist” as a form of hate speech under its Community Standards. That campaign was prompted by a similar email revelation, and a petition in opposition to the potential policy change garnered over 14,500 signatures within the first twenty-four hours.

In May 2021, Biddle also reported that despite Facebook’s claims that the change was under consideration, the platform and its subsidiary, Instagram, had already been applying the policy to content moderation since at least 2019, eventually leading to an explosive wave of suppression of social media criticism of Israeli violence against Palestinians that included the looming expulsion of Palestinians from their homes in Sheikh Jarrah, Israeli Occupation Forces’ brutalization of Palestinian worshippers in Al Aqsa mosque, and lethal bombardment of the Gaza strip in 2021.

Still Denied: Permission to Narrate

These 2021 waves of anti-Palestinian censorship across digital platforms prompted me to write an op-ed for Al Jazeera. I connected Palestinian History Professor Maha Nassar’s analysis of journalistic output related to Palestine over a fifty-year span to social media giants’ repression of Palestine. What Nassar found—thirty-six years after the late Palestinian intellectual Edward Said declared that Palestinians had been denied “Permission to Narrate”—was that an overabundance of writing about Palestinians in corporate media outlets was belied by how infrequently Palestinians are offered the opportunity to speak fully about their own experiences. I argued that the social media censorship of Palestine was a direct continuation of this journalistic anti-Palestinian racism despite the pretext of and capacity for digital platforms to serve as an immediate and widely accessible corrective to the omissions of corporate media. Palestinians are doubly silenced by social media censorship, once again denied “Permission to Narrate.”

Before, the sole culprit was the corporate media. Today, it’s matched by Silicon Valley.

I identified this phenomenon as “digital apartheid.”

At the time, I assumed this would be a one-off piece. The wide-scale social media censorship of Palestine in 2021 certainly seemed to be an escalation, but it also came on the cusp of what felt like a global narrative shift in the Palestinian struggle. Savvy social media use by Palestinians resisting displacement from Sheikh Jarrah made Palestinian oppression legible in seemingly unprecedented ways, which in turn helped promote increased inclusion of Palestinian voices and perspectives within corporate media outlets such as CNN.

So when Big Tech companies such as Meta tried to backpedal by ramping up censorship as Israel increased its colonial violence, it felt like a desperation born of unsustainability. Yes, Big Tech was erasing Palestinian voices, taking the baton from corporate media in an astoundingly egregious fashion, but this had to be temporary. Surely, the increased support for the Palestinian struggle born of a paradigm-shifting moment would eventually compel social media giants to desist.

To state the obvious, this was not the case, and what I thought would be a one-time topic became the focus of repeated freelance journalistic output. I wrote articles for Mondoweiss and The Electronic Intifada about various forms of digital repression, from blacklisting and harassment by online Zionist outfits such as Stopantisemitism.org and their affiliate social media accounts to deletion and censorship of Palestinian content on platforms like Meta and X (which was still Twitter at the time the bulk of these pieces were written).

It became all too clear that what had at first seemed like an escalation was now routine, as social media giants continued to heavily repress Palestinian voices, often around particular flashpoints such as Israeli bombardments of the Gaza strip—the so-called “mowing of the lawn.” Increasingly impressed by how digital repression of anti-Zionist and pro-Palestine content on social media platforms acts as an extension of Israel’s lethal colonial violence and racism against Palestinians, I started to think that a book about digital repression of Palestine and Palestinians could be a timely contribution to the critical trend towards analysis of how Big Tech reinforces systems of structural oppression. As writers, we approach broad topics with particular fascination, even obsession. Given my own interest in Big Tech’s role in suppressing the very narrative shifts on Palestine it inadvertently served to operationalize, as well as the potential friction between the imperially derived norms of censoriousness that govern corporate media and newer digital platforms, the vast bulk of my work focused on social media.

To be sure, there is no shortage of analysis about tech repression of Palestinians, by writers and academics like Jonathan Cook, Anthony Lowenstein, Mona Shtaya, Nadim Nashif, and Miriyam Auoragh (to name but a few). It is also crucial to center the necessary advocacy by organizations such as the aforementioned 7amleh, which is leading the charge to protect Palestinian digital rights, and the #NoTechforApartheid campaign. But I felt that a book about this topic published in a space not exclusively dedicated to Palestine could accomplish the modest task of helping affirm the relevance of digital repression of Palestinians and their allies to broader conversations about how, for all of its pretensions, Big Tech is a central cog within rather than a corrective to different systems of oppression and extraction. Indeed, as critics of technofeudalism and surveillance capitalism note, Big Tech’s predilection for exploitation arises from how it works within capitalism rather than displacing it outright.

Refusing the Language of Silence

So, on October 13, 2022, I did something that many writers do: I pitched a book of critical essays based on these articles about the digital repression of Palestine to a press. The pitch for Terms of Servitude: Zionism, Silicon Valley, and Digital/Settler-Colonialism in the Palestinian Liberation Struggle was accepted by The Censored Press and its partner, Seven Stories Press, in just over a month’s time.

Then, just a few days shy of one year later, Israel began its current genocide of Palestinians in Gaza.

Suddenly, putting words together felt both impossible and vampiric.

How could I think of making language in the face of the unspeakable?

Something in myself closed off. For the next few months, I moved with the sureness of abandonment. I attended demonstrations, co-organized events, planned campaigns, and continued to think of ways to keep Palestine in the classroom. But a book was the last thing on my mind. In fact, for a time, I couldn’t even write at all. Editors commissioned pieces from me, but all I could do was watch the cursor blink as the emails piled up and then stopped altogether after the solicitors finally learned the language of my silence.

The epiphany is a standard (if at times hackneyed) component of narratives. But fiction and experience share a dialectical relationship. Each one helps us make sense of the other.

Several important developments helped inspire a shift in my consciousness.

For one thing, I could never really escape from the task at hand, even as I did my best to hide. Lying in bed with no light but the dim blue glow of the phone to view recordings of atrocity upon atrocity, then digital restriction or outright deletion of the material in question, I realized that I was a near-constant witness to the very dynamics about which I had been trying to avoid writing.

Being asked to give feedback on brilliant writing by comrades in Palestine reminded me that writing and analysis play a particular role in liberation struggles.

I eventually came to realize that in addition to the immeasurable toll of physical destruction and extermination, the Zionist state’s latest genocide of Palestinians in Gaza is intended to inspire fear and surrender. Therefore, it is incumbent upon all people of conscience to use their platforms to advocate for Palestinian liberation and resist genocide. I have always identified as a writer, first and foremost. I realized that Terms of Servitude is a unique platform I have at my disposal to help advance this goal, however modestly.

And lastly, as a vast wave of criminalization of support for Palestine broke out across the United States, digital repression was once more at an all-time high. The egregiousness of Meta’s potential policy change, which prioritizes the protection of a colonial ideology under hate-speech frameworks while colonized Palestinians are undergoing genocide, is sharpened when we consider the ways that the company has already been enabling the Israeli state’s latest genocidal campaign: For instance, as reported by Zeinab Ismail for SMEX, Meta updated its algorithms following October 7 to hide comments from Palestine, ensuring that comments from Palestinians with a minimum 25 percent probability rating for containing “offensive” content were flagged, while the number was set to 80 percent for all other users.

Digital/Settler-Colonialism at Work

After October 7, my previous use of the term digital apartheid no longer felt adequate. Apartheid is one aspect of the Zionist colonization of Palestine, not the totality. Apartheid is an instrument of settler colonialism. Zionist-aligned tech suppression serves to alienate Palestinians from the digital sphere, but simply attributing this discrimination to “apartheid” obscures the full scope of violence that the Zionist enterprise poses to Palestinians. The term settler colonialism incorporates apartheid as part of a broader apparatus of violence, including land theft, elimination, and, as we continue to see play out in real-time, genocide. What Palestinians are up against is not (only) “digital apartheid” but a colonial application of digital technologies.

In 1976, Herbert Schiller explored how communications technologies function as a new weapon of Western imperialism, allowing a specific cadre of US governmental and corporate elites to use the global propagation of broadcast systems and programming as a means of securing US hegemony. Recalling the historical connection between the US government, military, and corporate capitalist interests and the development of the internet, Schiller’s insights are directly applicable to contemporary digital systems.

In 2019, Michael Kwet categorized the actions of Big Tech companies as “digital colonialism.” Using South Africa as a case study, Kwet compared the extractive attitude of tech companies that provided technology and internet access to South African schools for the purposes of enacting surveillance and data mining to the colonial corporatism of the Dutch East India Company. By “digital colonialism,” Kwet was referring to how Big Tech is one contemporary means by which counter-democratic US corporations engage in extractive processes against the rest of the world to shore up profits and ensure their dominance.

Kawsar Ali used the term “digital settler colonialism” to refer to “how the Internet can become a tool to decide who does and does not belong and extend settler violence online and offline” (p8). My framework combines these insights to explain how the digital dimensions of the Palestinian liberation struggle reflect a meeting point of colonial and settler-colonial designs.

I use the term digital/settler-colonialism to categorize this dynamic. I realize the phrase is far from perfect. For one thing, it’s rather indecorous. Frankly, it’s clunky.

Nevertheless, I believe its aesthetic shortcomings are compensated for by analytical precision, for digital/settler-colonialism captures the convergence of US Big Tech digital colonialism and Israeli settler colonialism. In doing so, it foregrounds the aggregate nature of the material conditions opposing Palestinian digital sovereignty.

Imagine a Venn diagram whose two spheres are digital colonialism and settler colonialism. Digital/settler-colonialism is the area formed where the two overlap.

Campaigns such as those opposing Meta’s prohibition on critical use of the term “Zionist” demonstrate the looming threat of digital/settler-colonialism at work. By applying public pressure to discourage tech moguls from implementing terms of service and community guidelines that mirror Israeli colonial and apartheid policy, these campaigns reflect the unique danger posed by corporate digital colonialism coming together with Israeli settler colonialism. But they also demonstrate how resisting digital/settler-colonialism can work by leveraging the potential friction between the imperatives of digital colonialism and settler colonialism. This approach echoes the framework of the Palestinian-led BDS movement, which prioritizes economic and political pressure as a means of ending Israeli colonial impunity and making investment in Israeli apartheid and military occupation too costly.

After all, while US tech companies are no friend to Palestinian liberation (not to mention any other freedom struggle), they’re also not a settler-colonial state dedicated to the elimination of an Indigenous people. They’re corporations driven first and foremost by the pursuit of unrestricted profits.

Granted, Israel has been deeply enmeshed in the tech world even as its tech sector has taken significant hits. The refinement of tech, particularly for purposes of rights deprivation, has granted the colonial state a unique global capital. For instance, though Israel is not a member of the imperialist North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a 2018 arrangement enables Israeli companies to sell weapons to NATO countries vis-à-vis the NATO Support and Procurement Agency. Writing in Electronic Intifada, David Cronin reports that Israeli weapons manufacturer Elbit Systems had procured new deals with NATO member countries since the start of Israel’s genocide of Palestinians in Gaza, and that NATO itself had expressed considerable interest in increasing collaboration. NATO military committee chair Rob Bauer even voiced admiration for how the IOF’s Gaza division used robotics and AI to monitor what he referred to as “border crossings”—a euphemism, as Cronin rightly notes, for Israel’s corralling of colonized Palestinians into the world’s largest open-air prison and maintaining the inhumane blockade to which it has subjected Gaza since 2007. And despite claims to the contrary, Israel has long deployed Pegasus spyware, used by repressive regimes the world over to target activists and journalists, as a tool of digital diplomacy. Inseparable from Israel’s routinized and continuously refined surveillance of Palestinians, Pegasus has also been used to deliberately target Palestinian activists involved in human rights work. Predictably, NSO Group, the cyber-(in-)security company that developed Pegasus, is capitalizing on Israel’s genocide and engaging in various PR and lobbying efforts to rebrand itself, hoping to overturn the US government’s sanctioning of its product.

The central role tech plays in Israel’s competitive status and reputation is also bolstered by how, for all of their bluster about supporting free speech, Big Tech companies generally have a habit of maintaining cozy relationships with oppressive regimes. For all of these reasons, the overlap between Israeli colonial designs and Big Tech operations can be considerable. For example, as Paul Biggar observes regarding Meta, the company’s three most senior leaders have pronounced connections to the Israeli state. Guy Rosen, the Chief Information Security Officer who Biggar identifies as the “person most associated” with Meta’s “anti-‘anti-Zionism’” policies, is Israeli, lives in Tel Aviv, and served in the IOF’s infamous Unit 8200. Meta founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg gave $125,000 to ZAKA, one of the organizations that fabricated and continues to spread the October 7 “mass rape” hoax. Sheryl Sandberg, former COO and current Meta board member, has been on tour spreading the very same propaganda. Biggar argues that these ties help explain the ease with which the IOF seems able to access WhatsApp metadata to slaughter Palestinians in Gaza indiscriminately.

But a convergence model is helpful in two respects. First, it helps recenter complicity—tech companies don’t have to facilitate Israel’s settler colonialism; to do so is an active choice on their part. Furthermore, maximum profit and the genocide of Palestinians are two separate goals, even as they can often overlap through the economic incentivization of imperialist militarism. Thus, at least in theory, it is possible to undermine digital/settler-colonialism by refining the potential instability between digital colonialism and settler colonialism by making the operation of the former process too costly when it facilitates the latter.

Resisting Digital/Settler-Colonialism

Social media has taken on an even more outsized role in this latest iteration of Zionist genocide. Palestinian journalists from Gaza use it to document genocide in real-time—even as they are directly targeted by Israel and subjected to frequent communications blackouts. Younger generations use it to find and share information about Palestine that is otherwise hidden by the corporate media. And, recalling Franz Fanon’s analysis of how the Algerian Liberation Front repurposed the radio, which began as an instrument of French colonial domination, in order to affirm dedication to the Algerian revolution, Palestinian, Lebanese, and Yemeni resistance fighters use social media to strike a powerful blow to the image of Israeli and US military impunity.

Of course, consciousness-raising has its limits. Western governments remain unwilling to meaningfully reverse support for Israel despite a vast trove of digital and analog documentation (not to mention the recent ruling by the International Court of Justice). This reflects the degree to which these governments’ functioning is predicated upon the dehumanization of Palestinians, an awareness powerfully captured by Steven Salaita’s description of “scrolling through genocide.”

But the reconfiguration of the conventions and possibilities of communication posed by Big Tech hegemony means that digital spaces remain a central avenue of global interconnection. As such, Palestinian access to social media and the internet continues to be obstructed by the powerful. And resisting digital/setter-colonialism in pursuit of Palestinian liberation remains a paramount undertaking.

First published at Project Censored.

Omar Zahzah is a writer, poet, organizer, and Assistant Professor of Arab and Muslim Ethnicities and Diasporas (AMED) Studies at San Francisco State University. Omar’s book, Terms of Servitude: Zionism, Silicon Valley, and Digital/Settler-Colonialism in the Palestinian Liberation Struggle, is forthcoming from The Censored Press, in partnership with Seven Stories Press, in fall 2025. Read other articles by Omar.