PRIMITIVE ACCUMULATION OF CAPITAL

Britain saw centuries of economic growth under Roman rule

The technologies introduced by the Romans after they conquered Britain led to the kind of economic growth seen in the industrial age

5 July 2024

A hoard of Roman gold coins found below the floor of a Roman house in Corbridge, UK

World History Archive/Alamy

After the Romans conquered Britain in AD 43, the technologies and laws they introduced led to centuries of economic growth of a kind once thought to be limited to modern industrial societies. That is the conclusion of an analysis of thousands of archaeological finds from this time.

“Over that period of about 350 years, you’re looking at roughly a two and a half [fold] increase in productivity per capita,” says Rob Wiseman at the University of Cambridge.

It has long been believed that economic growth in the ancient world depended on having more people and more resources, says Wiseman: to increase food production, say, required more land and more farm workers. This kind of growth is known as extensive growth.

By contrast, economic growth today is driven mainly by increased productivity, or intensive growth. Thanks to mechanisation and better breeds of plants and animals, for instance, more food can be produced from the same area of land with fewer workers.

Some recent studies have challenged the idea that intensive growth occurred only after the industrial age began, inspiring Wiseman and his colleagues to look at growth in Roman Britain from AD 43 to 400.

The team’s research was made possible by UK laws requiring archaeological investigations to be done when a site is developed, says Wiseman. “The result is there’s been tens of thousands of archaeological excavations done in this country. And, moreover, that data is publicly accessible.”

By looking at how the number of buildings changed over time, the researchers were able to get an idea of how the population of Roman Britain grew. There is a strong relation between the number of buildings and population size, says Wiseman.

To get an idea of economic growth, the team looked at three measures. One was the size of buildings, rather than the number of them. As people grow richer, they build bigger houses, says Wiseman.

Another measure was the number of lost coins found in digs. “These are things that have fallen through the floorboards, or they’ve been lost in the baths, or something like that,” he says.

The idea is that the more coins are in circulation, the more are likely to be lost. The team didn’t count hidden hoards of coins, as these reflect instability rather than growth.

The third measure was the proportion of crude pottery, such as cooking pots and storage pots, to more ornate pottery like decorated plates. Economic growth requires people to interact more and socialise more, which means “showing off” when guests are present, says Wiseman.

Based on these measures, the team found that economic growth exceeded that expected from population growth alone. They estimate that per capita growth was around 0.5 per cent between AD 150 and 250, slowing to around 0.3 per cent between AD 250 and 400.

“What we’re able to show is yes, after the Romans arrived, there was definitely intensive growth,” says Wiseman. The pace of growth rather than the kind of growth is what probably distinguishes the modern world from the ancient one, he says.

The researchers think that this growth was driven by factors such as the roads and ports built by the Romans, the laws they introduced making trading safer, and their technologies, such as more advanced grain mills and better breeds of animals for ploughing.

The higher growth between AD 150 and 250 may be a result of Britain catching up with the rest of the Roman world, says Wiseman. “You’re moving from a small tribal society where there’s not a lot of interaction going on to a world-spanning economy.”

What isn’t clear is whether this economic development made people happier or healthier. “Just because the productivity is going up doesn’t automatically mean that the welfare of Britons who were invaded and colonised was better under Rome,” says Wiseman. “That’s an open question.”

To investigate this, the researchers now plan to look at human remains to work out things such as how long people lived.

“I am convinced that they are right and that, indeed, intensive growth took place in Roman Britain,” says Alain Bresson at the University of Chicago, Illinois.

“A lot of archaeologists have noted compelling evidence for economic growth in Roman Britain, but this paper adds a welcome formal theoretical dimension to the discussion,” says Ian Morris at Stanford University, California.

However, Morris suspects that the lower average growth rate from AD 250 to 400 actually reflects high growth followed by rapid decline as the Roman empire began to break up. Further studies will resolve this, he says.

Journal reference:

Science Advances DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adk5517

National Trust’s largest ever survey might have uncovered two Roman villas

Two villas, the equivalent of a large country estate, are thought to have been uncovered at the Attingham Estate in Shropshire.

Two Roman villas are thought to have been identified at the Attingham Estate in Shropshire by a survey commissioned by the National Trust.

The non-invasive geophysical survey encompassed over 1000 hectares (2,471 acres), and is the largest of its kind ever carried out by the organisation.

This type of survey uses scanning and mapping technology, to provide a better understanding of Attingham’s archaeological remains to help the conservation charity develop its nature recovery plans for the area.

The area, which encompasses a portion of the buried Roman city of Wroxeter (Viriconium Cornoviorum) is cared for by English Heritage, and some of the land surrounding the city.

Among the features identified by the survey work was evidence for what are believed to be two previously unknown Roman villas and a Roman roadside cemetery, on a road leading out of Wroxeter.

National Trust said the two rural villas – the equivalent of a large country estate – show evidence of at least two construction or occupation phases, along with floor plans with internal room divisions and associated outbuildings.

The conservation charity explained: “Villas of this nature in the UK were usually heated by hypocausts (underfloor heating), they often had their own bath houses and were decorated with painted plaster and mosaic floors. It is likely that both villas identified would have had similar features. Only six other Roman villas are currently known in Shropshire.”

Eight ditched enclosures and associated remains, many believed to be Iron-Age or Romano British farmsteads, have also been detected by the survey.

In addition, evidence for several Roman roads to the west of Wroxeter were identified and surveys have “substantially enhanced archaeologists’ understanding of the settlement activity immediately outside the defences of the city and the changing use of the area during Roman times,” it said.

National Trust Archaeologist Janine Young explained: “This new geophysical survey has really transformed our knowledge by establishing a comprehensive ‘map’ of what is below our feet, providing us with a fascinating picture of the estate’s hidden past, revealing previously unknown sites of importance.”

John Deakin, Head of Trees & Woodlands at the National Trust said the project will help Attingham to work with its farm tenants to identify opportunities for tree establishment across its land in North Shropshire “whilst ensuring the protection of heritage features”.

“This has been a one-of-a kind investment for the National Trust, due to the size of the estate being mapped and the complexities presented by the rich archaeological heritage of this area of North Shropshire.

“Learnings from this project will help inform the Trust’s approach to planning for nature and heritage together in different landscapes, supporting its ambitious work to improve the state of nature in the UK.”

The project was supported by bequests and donations to the National Trust to support its nature conservation, tree planting and heritage work.

Archaeologists find evidence of how Iron Age Britons adapted to the Roman conquest in Winterborne Kingston

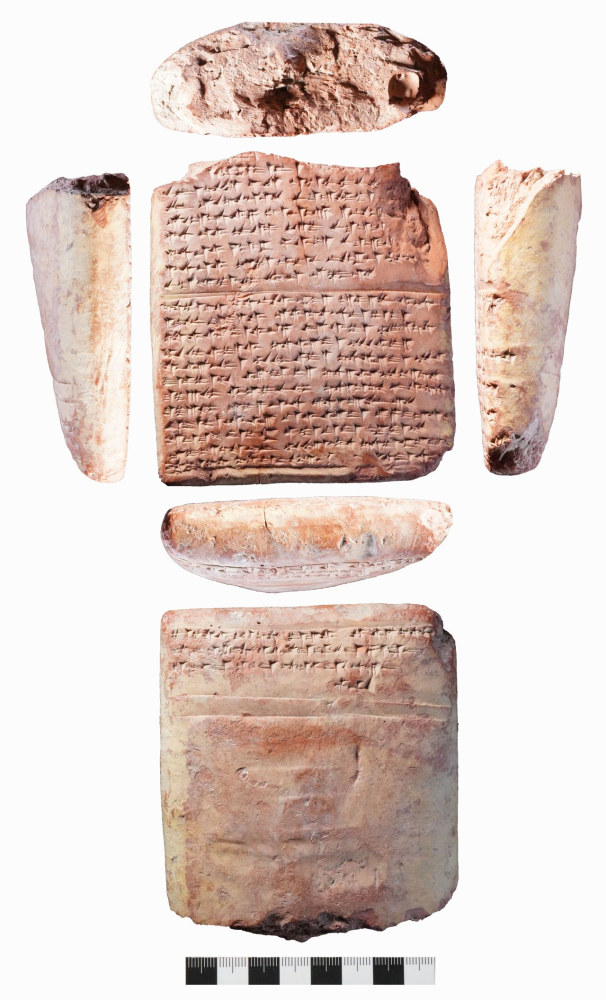

Archaeologists from Bournemouth University (BU) have discovered human remains and artifacts which give new insight into how early Britons adapted to life after the Roman invasion.

For over fifteen years, Bournemouth University staff and students have excavated Iron Age settlements at the Winterborne Kingston site. Although human remains and pre-Roman artifacts have been found before, these are the first discoveries that can be used to reconstruct the lives of those who lived through the invasion of Dorset.

Amongst the grave goods excavated from the 2000-year-old burial pits and graves are Roman-style wine cups and flagons, which suggest that Mediterranean alcohol had become a popular addition to British life around the time of the Roman conquest in AD 43.

“Being incorporated into the Roman Empire was one of the biggest societal changes in British history,” in a press release said Dr Miles Russell, Principal Academic in Archaeology at Bournemouth University, who is leading the dig.

“It’s all very well learning about the Roman legions and their conquests, but we wanted to find the farmsteads and burials that tell us what life was like for ordinary Britons and what happened to them at the time – did they become part of the wider empire, did they resist, or did they carry on living as they had always done? So finding a site like this was critical,” he added.

Three graves in particular indicate the extent to which the local Durotriges tribe partially integrated into certain Roman ways of life. The first contained the bodies of two women, aged in their thirties who had been buried together. The student archaeologists found a Roman-style wine flagon and goblets alongside the remains.

“The women were buried in the traditional Iron Age way – on their side in a foetal position. So, although the grave was dug ten to twenty years after the Romans arrived, in the mid to late first century AD, it’s clear that the local people are not becoming Roman in a big way, merely taking things from the Romans that enhance and improve their life, in this instance wine,” Dr Russell explained.

Another grave contained two dog burials which is significant because hunting dogs were very important to Iron Age society and were a key British export for the Roman elite. Despite their status, Dr Russell suspects the dogs may in this case have been sacrificed to the gods because of their placement in the grave and the fact they both died at the same time.

A third grave contained the remains of a man who had been buried in more classic Roman way, with arms folded across his chest, in a coffin, a large number of iron nails being found alongside his remains.

“Our more Roman-style graves, set down in the second and third century are low in artifacts,” explained Paul Cheetham, co-director of the project. “This suggests that although burial customs were changing over time, the farmers of this area, despite being part of a wider empire, weren’t benefitting much from belonging to the Roman world and were maintaining more native culture patterns.”

Although the wine vessels excavated from the early graves look, Roman, the team has identified that they were local copies of Mediterranean-style vessels manufactured in nearby Poole harbor.

“They are made from a local fabric by a local potter, but they are very much in a Roman style and not something we had found in local traditions before,” said Kerry Barras, a visiting researcher at Bournemouth University and Finds Manager at the site. “So they are taking their designs and copying them. They are mixing their traditions, taking on some of the Roman culture and influence, but they were found by a crouched burial which is not Roman and a part of more regional British tribal culture,” she added.

To help us understand more about life in early Roman Dorset, all human remains and artifacts will be subjected to additional testing at Bournemouth University. Next summer, Dr. Russell and the group of employees and students will revisit the location to conduct additional excavations on the surrounding land.

Cover Photo: Bournemouth University