Oldest living culture: Our new research shows an Indigenous ritual passed down for 500 generations

We often hear that Aboriginal peoples have been in Australia for 65,000 years, "the oldest living cultures in the world." But what does this mean, given all living peoples on Earth have an ancestry that goes back into the mists of time?

Our new discoveries, published July 1 in the scientific journal Nature Human Behaviour, shed new light on this question.

Under the guidance of GunaiKurnai Elders, archaeologists from the GunaiKurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal Corporation and Monash University excavated at Cloggs Cave near Buchan, in the foothills of the high country near the Snowy River in East Gippsland, Victoria.

What we found was extraordinary. Under the low, subdued light in the depth of the cave, buried under layers of ash and silt, two unusual fireplaces were revealed by the tip of the trowel. They each contained a single trimmed stick associated with a tiny patch of ash.

A sequence of 69 radiocarbon dates, including on wood filaments from the sticks, date one of the fireplaces to 11,000 years ago, and the deeper of the two to 12,000 years ago, at the very end of the last Ice Age.

Matching the observed physical characteristics of the fireplaces with GunaiKurnai ethnographic records from the 19th century shows this type of fireplace has been in continuous use for at least 12,000 years.

Enigmatic sticks smeared with fat

These were no ordinary fireplaces: the upper one was the size of the palm of a human hand.

Sticking out from the middle of it was a stick, one slightly burned end still stuck into the middle of the ashes of the fire. The fire had not burned for long, nor did it reach any significant heat. No food remains were associated with the fireplace.

Two small twigs that once grew from the stick had been trimmed off, so the stem was now straight and smooth.

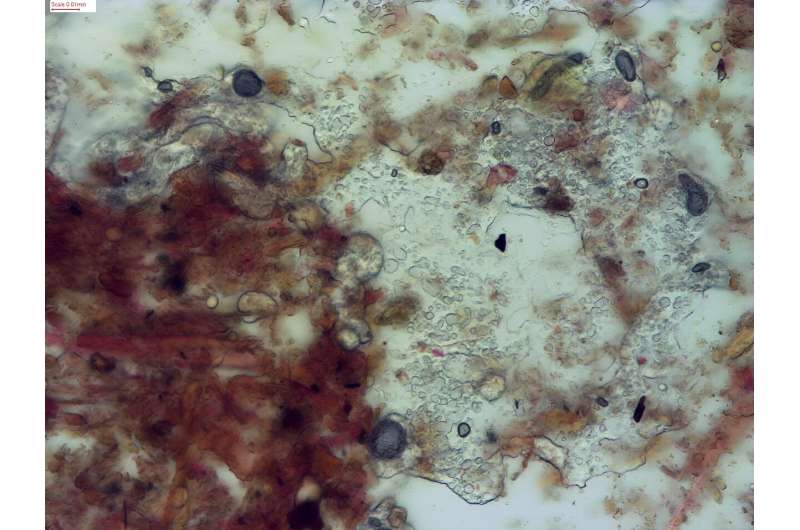

We performed microscopic and biochemical analyses on the stick, showing it had come into contact with animal fat. Parts of the stick were covered with lipids—fatty acids that cannot dissolve in water and can therefore remain on objects for vast lengths of time.

The trimmings and layout of the stick, tiny size of the fire, absence of food remains, and presence of smeared fat on the stick suggest the fireplace was used for something other than cooking.

The stick had come from a Casuarina tree, a she-oak. The branch had been broken and cut when green. We know this because of the splayed fibers at the broken end. The stick was never removed from the fire during its use; we found it where it was placed.

A second miniature fireplace slightly deeper down in the excavation also had a single branch emanating from it, this one with an angled-back end like on a throwing stick, and with five small twigs trimmed flush with the stem. It had keratin-like faunal tissue fragments on its surface; it too had come into contact with fat.

The role of these fireplaces in ritual

Local 19th-century ethnography has good descriptions of such fireplaces, so we know they were made for ritual practices performed by mulla-mullung, powerful GunaiKurnai medicine men and women.

Alfred Howitt, government geologist and pioneer ethnographer, wrote in 1887:

"The Kurnai practice is to fasten the article [something that belonged to the victim] to the end of a throwing stick, together with some eaglehawk feathers, and some human or kangaroo fat. The throwing stick is then stuck slanting in the ground before a fire, and it is of course placed in such a position that by-and-by it falls down. The wizard has during this time been singing his charm; as it is usually expressed, he "sings the man's name," and when the stick falls the charm is complete. The practice still exists."

Howitt noted that such ritual sticks were made from Casuarina wood. Sometimes the stick mimicked a throwing stick, with a hooked end. No such miniature fireplace with a single trimmed Casuarina stem smeared with fat had ever been found archaeologically before.

500 generations

The miniature fireplaces are the remarkably preserved remains of two ritual events dating back 500 generations.

Nowhere else on Earth have archaeological expressions of a very specific cultural practice known from ethnography, yet traceable so far back, previously been found.

GunaiKurnai ancestors had transmitted on Country a very detailed, very particular cultural knowledge and practice for some 500 generations.

GunaiKurnai Elder Uncle Russell Mullett was on site when the fireplaces were excavated. As the first one was revealed, he was astounded:

"For it to survive is just amazing. It's telling us a story. It's been waiting here all this time for us to learn from it. Reminding us that we are a living culture still connected to our ancient past. It's a unique opportunity to be able to read the memoirs of our Ancestors and share that with our community."

What does it mean to be one of the oldest living cultures in the world? It means despite millennia of cultural innovations, the Old Ancestors also continued to pass down cultural knowledge and know-how, generation after generation, and have done so since the last Ice Age and beyond.

More information: Bruno David et al, Archaeological evidence of an ethnographically documented Australian Aboriginal ritual dated to the last ice age, Nature Human Behaviour (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41562-024-01912-w

Journal information: Nature Human Behaviou

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()

Aboriginal ritual passed down over 12,000 years, cave find shows

Sorcery in Australian Cloggs Cave may be World’s Oldest Known Culturally Transmitted Ritual

Two sticks found in a cave in Australia show signs of processing that perfectly match Aboriginal sorcery and curse-making practices described in the 19th century. Approximately 11,000–12,000 years have been estimated for the sticks, making this the longest period of time that we have evidence for a cultural practice continuing anywhere in the world.

The discovery may represent the oldest known, culturally transmitted ritual—one that persisted among local people from the last ice age to colonial times, according to a study published today in Nature Human Behaviour.

The finds were made in southeast Australia’s Cloggs Cave, a rich archeological site. Situated atop a limestone bluff with a view of the verdant Australian Alps foothills, the cavern descended approximately 12 meters below the surface, preserving an extensive legacy of Aboriginal culture. Human activity there dates back up to 25,000 years, according to earlier research.

Cloggs Cave, in Victoria’s Gippsland region, lies within the lands of the GunaiKurnai people. Representatives of the GunaiKurnai decided in 2009 that they wanted their history properly investigated and began working with anthropologists at Monash University.

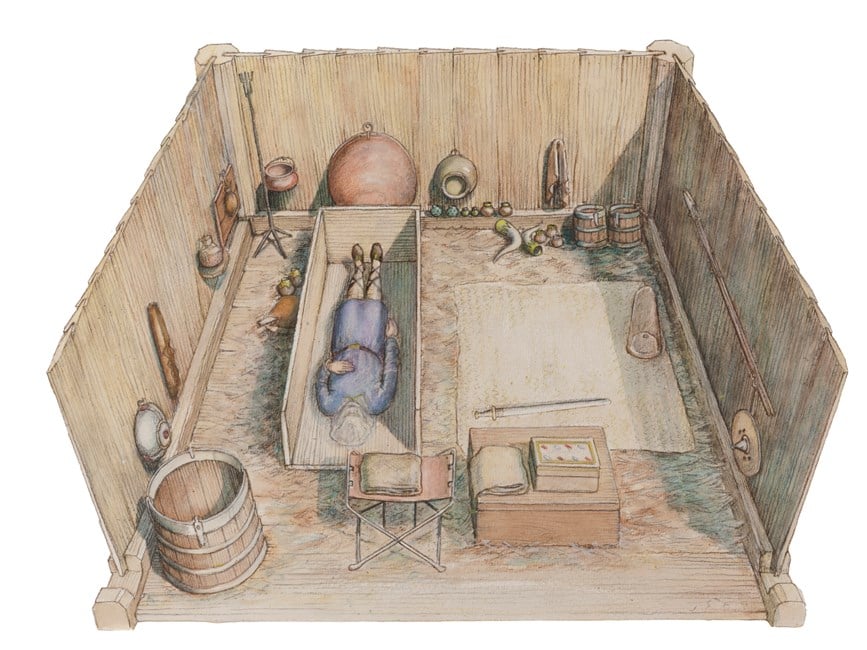

Around 6,000 years ago, a large portion of the cave turned into a sinkhole, which resulted in the juxtaposition of objects from wildly disparate ages. Professor Bruno David and associates decided to concentrate on a section of the cave that was not damaged in the collapse as a result. A 40-centimeter (16-inch) long, slightly burned Casuarina stick that was surrounded by limestone rocks emerged from a hand-sized fireplace. The stick was carbon-dated as approximately 12,000 years old, making it the oldest surviving wooden artifact found in Australia.

Anything wooden would rarely last that long, and the stick displayed even more remarkable qualities. Nothing like what is seen for something that was once part of a fire for warmth or food, the singeing at one end suggested it had been briefly placed in a cool fire. The stick carried lipids from human or animal fat, and twigs branching off had been carefully removed.

Further digging revealed a similar Casuarina stick, approximately a thousand years younger, but processed in the same way. Further research yielded a more comprehensive picture: Both sticks rested atop miniature fireplaces, which were little more than stone enclosures the size of palms filled with grass and twig ashes that seemed to have burned for a very short time. The sticks, the older one about 40 centimeters long and the younger one about half that length came from two species of Casuarina, flowering pine trees native to Australia with a long history of ceremonial use.

Surviving GunaiKurnai people had lost the cultural memory of what the sticks might have been used for. Researchers have therefore analyzed old ethnographic texts, which put everything in context as the evidence accumulated. In 1887, government geologist Alfred Howitt described rituals of the sorcerers who the local people called mulla-mullung. Other ethnographic texts associated Casuarina sticks with sorcery as well.

Howitt wrote in-depth accounts of mystical practices to cure the sick or curse enemies, drawing on both personal observations and accounts from Aboriginal people. One of these reports has a startling resemblance to the evidence found in the cave. A piece of clothing, a hairpiece, or a piece of food scrap was obtained by the sorcerer and attached to the end of a stick dipped in human or kangaroo fat in order to harm an enemy. The stick was then placed next to a small fire, and the mulla-mullung sung the name of the intended victim until the stick fell into the flames, enacting a fateful spell.

According to Bruno David, a lead author of the new paper and an archaeologist at Monash, the convergence of archaeological evidence and ethnographic accounts shows just how long Aboriginal traditions have survived.

“That’s 12,000 years of continuity, passing down knowledge from one generation to the next, of a cultural practice that has remained almost intact along 500 generations,” he says. “That’s absolutely remarkable.”

Rather than being a living space, the cave seems to have served mostly as a secluded den of ritual. In a series of discoveries spanning about 23,000 years, archaeologists have found ceremonial arrangements of stones, broken stalactites, a small grindstone, patches of calcite powder, and quartz crystals.

The discovery is published open access in Nature Human Behaviour.

Cover Photo: Jean-Jacques Delannoy 2019.