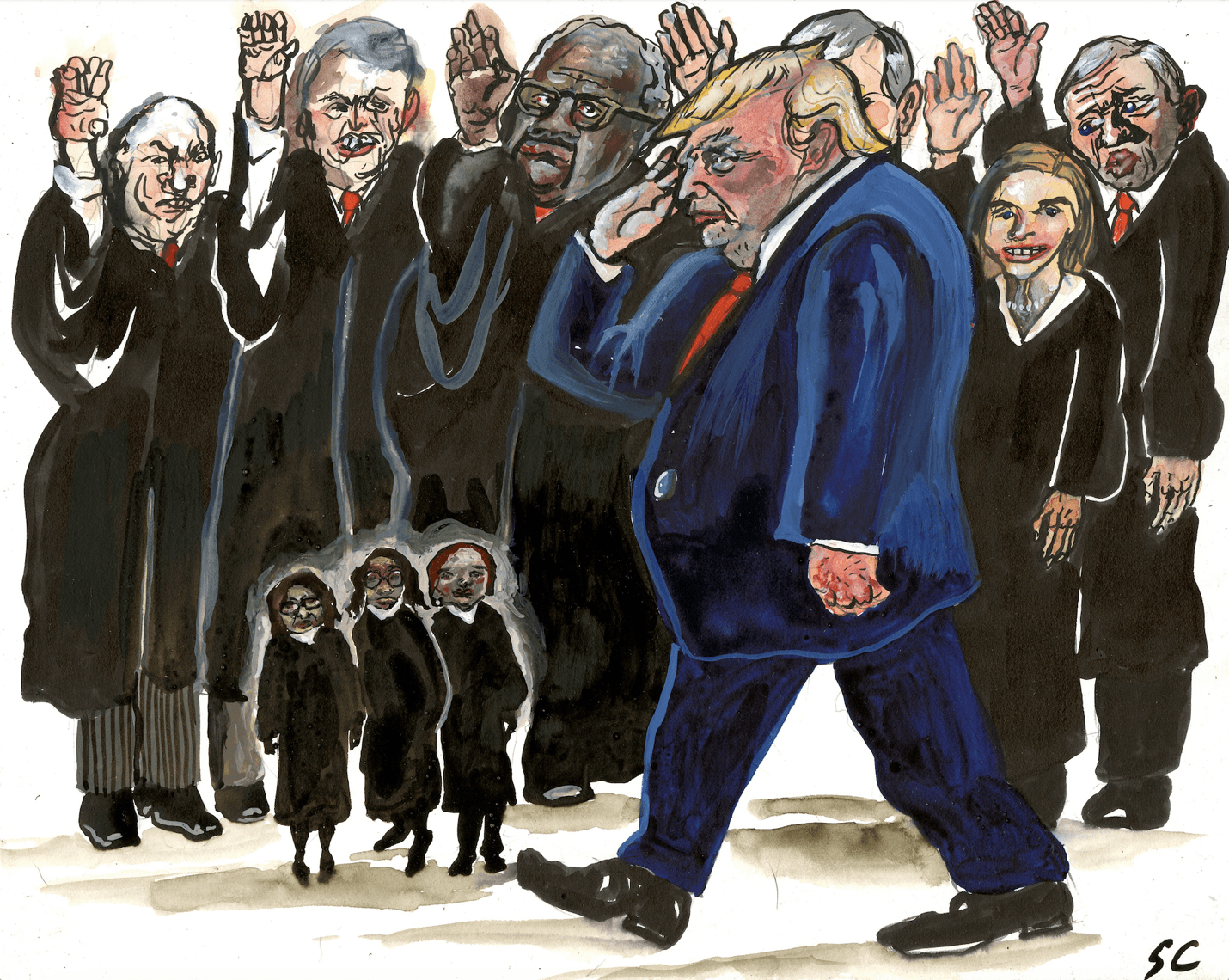

Illustration by Sue Coe.

Art by Sue Coe.

A fascist revival

The following lines, from a sermon delivered at Riverside Church in 1938, were resurrected after the election of Trump in 2016: “When and if fascism comes to America, it will not be labelled ‘made in Germany’; it will not be marked with a swastika; it will not even be called fascism; it will be called, of course, ‘Americanism’.” Trump and his minions proclaimed, “America First” and “Make America Great Again.” Charles Lindbergh not Hitler was their avatar, though the former of course admired the latter. Tucker Carlson on Fox News was Trump’s unofficial media spokesman; he didn’t need to employ his own Goebbels.

But recent developments suggests that pre-war Germany may after all turn out to be the ursprung of the emergent American fascism. Instead of Jews and Roma, immigrants from Mexico, Central America, Venezuela, Haiti and the Middle East are the “vermin,” according to candidate Trump, “poisoning the blood” of the American body politic. And in place of the enfeebled, 86-year-old President Paul von Hindenburg clearing the path for Hitler’s elevation, it’s the frail, 82-year old President Joe Biden allowing Trump’s-re-ascension. History doesn’t repeat itself, the saying goes, but sometimes it rhymes.

How Hitler came to power

Hitler’s ultimate rise to power was the result neither of a popular vote nor a coup, but an “Enabling Act,” or more precisely, “The Law to Remedy the Distress of the People and the  Reich.” The legislation submitted to the German Reichstag (parliament) on March 23, 1933, enabled Hitler and his cabinet to 1) make laws without participation of the Reichstag; 2) enact measures that violated the German constitution; 3) implement new laws immediately; 4) allow the government to make foreign treaties without input from the Reichstag; and 5) sunset the act after four years.

Reich.” The legislation submitted to the German Reichstag (parliament) on March 23, 1933, enabled Hitler and his cabinet to 1) make laws without participation of the Reichstag; 2) enact measures that violated the German constitution; 3) implement new laws immediately; 4) allow the government to make foreign treaties without input from the Reichstag; and 5) sunset the act after four years.

Hitler and his cabinet took no chances on its passage. They surrounded the Reichstag and filled its galleries with angry and armed stormtroopers (“brownshirts”); arrested or barred members of the opposition German Communist Party; and threatened vacillating legislators from the Center Party. The only remaining voice of opposition belonged to Otto Wels, head of the Social Democrats (SPD), the former governing party of the Weimar Republic. His speech was greeted with jeers and epithets:

“After the persecutions that the Social Democratic Party has suffered recently, no one will reasonably demand or expect that it vote for the Enabling Act proposed here. …Never before, since there has been a German Reichstag, has the control of public affairs by the elected representatives of the people been eliminated to such an extent as is happening now, and is supposed to happen even more through the new Enabling Act….But we stand by the principles enshrined in [our Constitution], the principles of a state based on the rule of law, of equal rights, of social justice…. We greet the persecuted and the oppressed.”

The Enabling Act easily gathered the required 2/3 vote, and Wels quickly fled the country. On July 12, Goebbels gloated: “SPD dissolved. We won’t have long to wait for the total state.” A day later, all non-Nazi political parties were banned, and the stiff armed Hitlergruß and “Heil Hitler” greeting were made mandatory for state employees.

The Enabling Act gave Hitler carte blanche to assume dictatorial powers. He banned opposition parties; forced trade unions to bend to his will; intimidated, jailed or murdered dissidents; established concentration camps; implemented harsh sanction on the nation’s Jews; forged alliances with the other European fascist powers, notably Italy and Spain; and undertook a massive program of rearmament. Six years later, Hitler would use his absolute authority to invade Poland, start the war in Europe, and perpetrate the genocide of Jews, Roma, queers, and others. The Enabling Act was renewed every four years and only expired with the demise of the Reich in 1945.

A majority of the U.S. Supreme Court gives Trump the Hitler salute

The Supreme Court of the United States two weeks ago passed its own enabling act, a virtual “Sieg Heil” to Donald Trump. In a case called United States v. Donald Trump, they agreed with the accused that the U.S. Constitution confers upon presidents near complete immunity from prosecution. Like a Roman emperor, he is legibus solutus, above the law.

The case arose from charges that Trump, following the November 2020 election, engaged in election interference by coercing the U.S. justice Department, supporting the establishment of fake, state electors, and encouraging a mob to storm the U.S. Congress to stop the electoral count. After a panel of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the ex-president lacked immunity from criminal prosecution, the case was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. The justices heard oral arguments on April 24, 2024, and issued their ruling on July 1, 2024, the final day of the term. Their dilatoriness all but ensured the case would not go to trial before the November election.

The six, conservative justices – Roberts, Alito, Thomas, Kavanaugh, Barrett, and Gorsuch — concluded that presidents enjoyed absolute immunity from prosecution for official , executive branch acts such as pardons, military command, immigration, and implementation of the laws. They also had “presumptive immunity” for all other, unspecified acts within the “outer perimeter” of presidential responsibilities. Only unofficial actions, also unspecified, were subject to criminal prosecution. Thus, in the case at hand, Trump was immune from prosecution for attempting to force the U.S. Department of Justice to interfere in the election because those communications were official acts. His calls to Mike Pence to fraudulently reject the election results were immune from prosecution since presidents are conducting official work when they discuss with vice presidents their respective responsibilities. Consideration of the president’s motives for an official act were also barred. Thus, it made no difference at all to the conservative justices that the capital rioters, with Trump’s blessing, proposed to lynch Mike Pence.

The king’s two bodies

The Court’s specific arguments, no less than their constitutional bases, are risible. When candidate Trump plots to overturn election results, he can be prosecuted. But when President Trump outlines the plot in an email to his Attorney General, the evidence is inadmissible. When the candidate urges the January 6 mob to storm the capital and halt the electoral count, he can be indicted. But when the president conveys that message in a speech or text message, the evidence is excluded because “most of a president’s public communications are likely to fall within the outer perimeter of his official responsibilities.”

According to medieval, political theology, the king has two bodies, one mortal, the other immortal, thus “The kings is dead. Long live the king!” The Supreme Court has endowed the U.S. presidency with two bodies, one subject to law the other not. The candidate is mortal, the president divine, but the latter they conclude, always supersedes the former.

The U.S. Constitution, the putative basis of Supreme Court rulings, says otherwise. Its authors were a disputatious lot, but they uniformly agreed that the president was not a king and must be subject to the law. Hamilton argued in the Federalist Papers that “the president would be amenable to personal punishment and disgrace.” Article 1, sec. 6, clause 10 of the Constitution grants U.S. Senators and Representatives immunity from prosecution only during their congressional attendance and transportation to and from Congress (a lengthy process in the late 18th Century). But even that immunity is partial. They can still be prosecuted for “treason, felony, or breach of the peace” – a capacious exception! Nowhere in the Constitution is the president granted even limited immunity.

At the Constitutional Convention, James Madison briefly raised the question of presidential immunity, but his colleagues balked. State ratifying conventions instead endorsed the idea that the U.S. president could, as one delegate wrote: “be proceeded against like any other man in the ordinary course of law.” Indeed, the whole point of the American Revolution was to dispense with the rule of a king. The colonists’ chief grievance against “the present king of Great Britain” was that he demonstrated a “history of repeated injuries and usurpations,” the result of which was “the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States….He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.”

Article 1 (section 3, clause 7 ) of the Constitution specifically mentions the president’s potential, criminal culpability: “Impeachment shall not extend further than to removal from Office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any Office of honor, Trust or Profit under the United States: but the Party convicted shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgment and Punishment, according to Law . The six justices agreed that the clause does not mean a president must be impeached and convicted before being charged with a crime. But even if he is convicted, he still may not be charged with a crime for any official act!

Three Supreme Court justices — Sotomayor, Kagan and Jackson — wrote in dissent of the majority opinion. They pulled no punches:

“Looking beyond the fate of this particular prosecution, the long-term consequences of today’s decision are stark. The Court effectively creates a law-free zone around the President, upsetting the status quo that has existed since the Founding. This new official-acts immunity now ‘lies about like a loaded weapon’ for any President that wishes to place his own interests, his own political survival, or his own financial gain, above the interests of the Nation. The President of the United States is the most powerful person in the country and possibly the world. When he uses his official powers in any way, under the majority’s reasoning, he now will be insulated from criminal prosecution. Order the Navy’s Seal Team Six to assassinate a political rival? Immune. Organize a military coup to hold power? Immune. Take a bribe in exchange for a pardon? Immune, immune, immune….In every use of official power, the President is now a king above the law.”

The question now is whether Sotomayor’s dissent will be a rallying cry that helps stop Donald Trump from once more assuming the presidency, or an epitaph for democracy, like the one issued by Otto Wels in 1933. The Supreme Court has issued its Enabling Act, and an avowed dictator is waiting to use it.

_0000.jpg)

Claire Mohamed-Petit

Claire Mohamed-Petit