Pro-government demonstration in Salamanca, Francoist Spain, in 1937 – CC0

“Now is the time of monsters.”

– Antonio Gramsci

Two recent events have shattered complacency about the specter of a fascist takeover globally that a number of us have been warning about for some time now. In Europe, far-right parties scored impressive gains in the elections to the European Parliament in June. In Germany, the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and other like-minded parties got 15.9 percent of the vote, forcing the long-time second-placer Socialist Party to third place. In France, President Emmanuel Macron’s centrist alliance gathered just 14.6% of the vote while Marine Le Pen’s National Rally (Rassemblement National) took in 31.3% of the vote. The results prompted Macron to an ill-advised decision to immediately dissolve the French Parliament and call a snap election, which resulted in a devastating first round victory for Le Pen’s party.

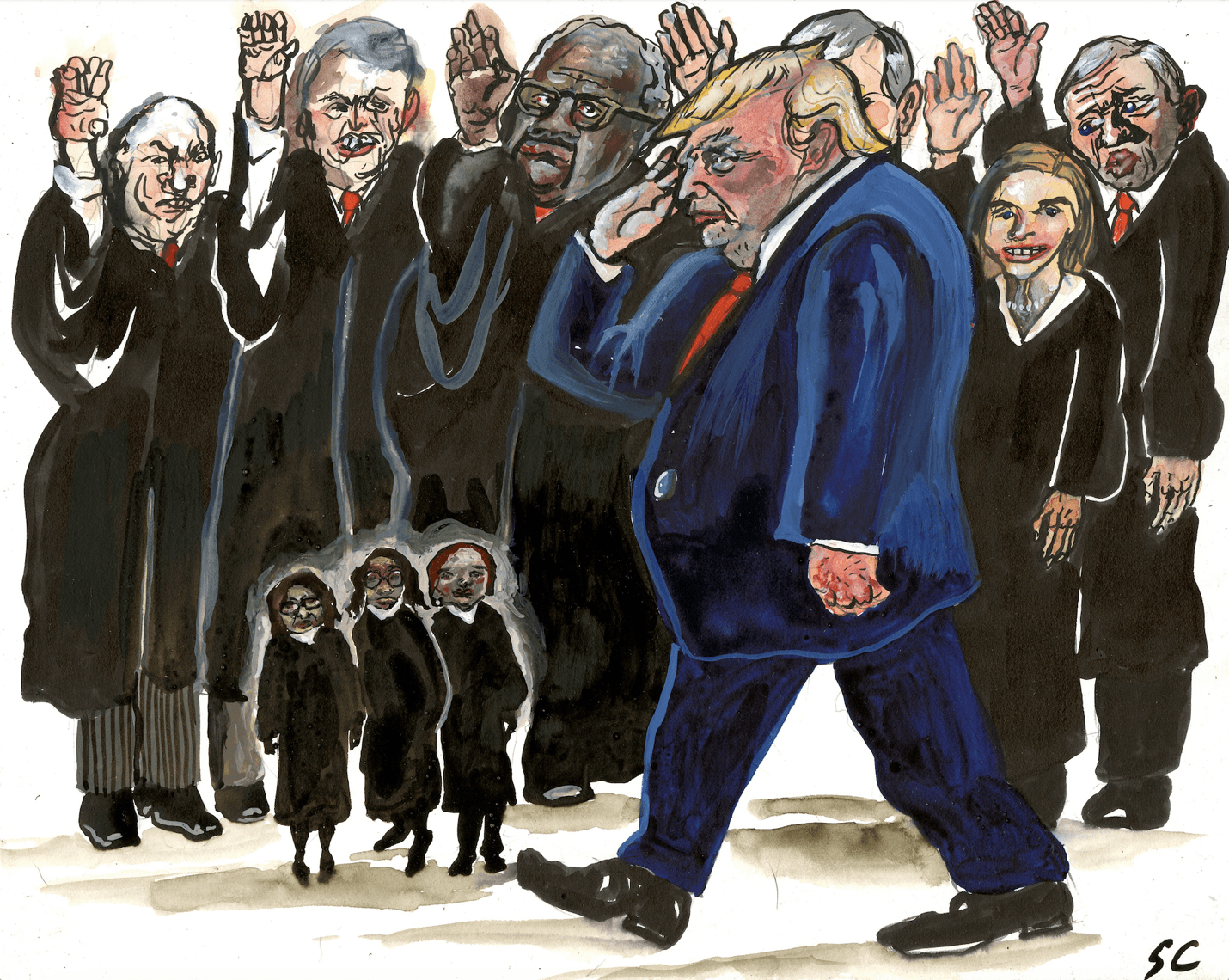

In the United States, President Joe Biden made a second Trump presidency come immeasurably closer with a horrible performance in a debate with Trump on June 27 that simply confirmed what most voters have discerned for some time now: that Biden is simply too old to function effectively in what is arguably the most powerful job in the world.

This has made many progressives and liberals fear that the enemy is at the gates. They are right. Gramsci depicted his times, the early decades of the 20th century as a time when “the old world is dying and the new world struggles to be born. Now is the time of monsters.” That line might well describe where our world is at today.

How I Got Interested in Fascism

My interest in fascism started when I went to Chile in 1972 to do field research during the presidency of Salvador Allende, which was cut short by a military coup on Sept 11, 1973. I arrived in the capital, Santiago, in the midst of the Chilean winter, greeted by tear gas and skirmishes of opposing political groups in the aftermath of a demonstration. Hauling two suitcases, I made it with great difficulty from the bus depot to the historic Hotel Claridge.

I had gone to Chile to study how the left was organizing people in the shantytowns or callampas for the socialist revolution that the Popular Unity government had initiated. A few weeks in Santiago disabused me of the impression of a revolutionary momentum that I had gathered reading about events in Chile in left-wing publications in the United States. People on the left were constantly being mobilized for marches and rallies in the center of Santiago, and increasingly, the reason for this was to counter the demonstrations mounted by the right. My friends brought me to these events, where there were an increasing number of skirmishes with right-wing thugs.

I noticed a certain defensiveness among participants in these mobilizations and a reluctance to be caught alone when leaving them, for fear of being harassed or worse by roaming bands of rightists. The revolution, it dawned on me, was on the defensive, and the right was beginning to take command of the streets. Twice I was nearly beaten up because I made the stupid mistake of observing right-wing demonstrations with El Siglo, the Communist Party newspaper, tucked prominently under my arm. Stopped by some Christian Democratic youth partisans, I said I was a Princeton University graduate student doing research on Chilean politics. They sneered and told me I was one of Allende’s “thugs” imported from Cuba. I could understand if they thought I was being provocative, with El Siglo tucked under my arm. Thankfully, the sudden arrival of a Mexican friend saved me from a beating. On the other occasion, my fleet feet did the job.

When I looked at the faces of the predominantly white right-wing crowds, many of them blond-haired, I imagined the same enraged faces at the fascist and Nazi demonstrations that took control of the streets in Italy and Germany. These were people who looked with disdain at what they called the rotos, or “broken ones,” that filled the left-wing demonstrations, people who were darker, many of them clearly of indigenous extraction.

My experience in Chile did two things to me. One, it gave me an abiding academic fascination with counterrevolutionary movements. Two, it turned me into a life-long activist with a deep loathing for the far right and instilled a commitment to fight authoritarianism and the far right. In many ways, these contradictory drives have determined my personal, political, and academic trajectories.

Is It Fascism?

Fast forward to the present. When far-right personalities and movements started popping up during the last two decades, there was, in some quarters, strong hesitation to use the “f” word to describe them. With my experience in Chile, the Philippines, and other countries behind me, I had no such qualms. This apparently was the reason I was invited by the famous Cambridge Union for a debate on the topic “This House Believes That We Are Witnessing a Global Fascist Resurgence” on April 29, 2021, where I would speak for the affirmative. Of course, a great incentive for agreeing to participate was that one of my intellectual heroes, John Maynard Keynes, had been involved in a famous Cambridge Union debate. Joining me in the debate by Zoom that evening were New York University Professor Ruth Ben Ghiat, Russian journalist Masha Gessen, staff writer for the New Yorker, the prominent historian of the Second World War Sir Richard Evans, and Isabel Hernandez and Sam Rubinstein, two Cambridge University students.

In that debate, I said that a movement or person must be regarded as fascist when they fuse the following five features: 1) they show a disdain or hatred for democratic and progressive principles and procedures; 2) they tolerate or promote violence; 3) they have a heated mass base that supports their anti-democratic thinking and behavior; 4) they scapegoat and support the persecution of certain social groups; and 5) they are led by a charismatic individual who exhibits and normalizes all of the above. It is how they fuse these five features together that accounts for the uniqueness of particular fascist leaders and movements.

Not surprisingly, Donald Trump figured prominently in that debate. And one of my main arguments was that Donald Trump and the Jan 6, 2021, insurrection showed that the distinction between “far right” and “fascist” is academic. Or one can say that a “far-rightist” is a fascist who has not yet seized power, for it is only once they are in power that fascists fully reveal their political propensities, that is, they display all of the five features mentioned above. By the way, the Cambridge audience agreed with me. The Cambridge Independent carried the news the next day that “the motion was carried with 38 votes in favour, 28 against, and 2 abstentions.” Thank god, I didn’t let Keynes down.

Fascists and Counterrevolutionaries

In my work on the right, I have used the word “counterrevolutionary” interchangeably with the word “fascist.” Here I have been greatly indebted to the great historian of counterrevolution, Arno Mayer, who distinguished between the three actors in what he called the “counterrevolutionary coalition:” reactionaries, conservatives, and counterrevolutionaries. “Reactionaries,” said Mayer, “are daunted by change and long for a return to a world of a mythical and romanticized past.” Conservatives do not make a fetish of the past, and whatever the makeup of civil and political society, their “core value is the preservation of the established order.”

Counterrevolutionaries are more interesting theoretically and more dangerous politically. They may have, like the reactionaries, illusions about a past golden age, and they share the reactonaries’ and conservatives’ “appreciation, not to say celebration, of order, tradition, hierarchy, authority, discipline, and loyalty.” But in a world of rapid flux, where the old order has become unhinged by the emergence of new political actors, “counterrevolutionaries embrace mass politics to promote their objectives, appealing to the lower orders of city and country, inflaming and manipulating their resentment of those above them, their fear of those below them, and their estrangement from the real world about them.” Counterrevolutionaries or fascists, to borrow from another great historian, Barrington Moore, seek to “make reaction popular.”

Fascism as a Global Phenomenon

The rise of fascism is a global phenomenon, one that cuts through the North-South divide.

Narendra Modi has made the secular and diverse India of Gandhi and Nehru a thing of the past with his Hindu nationalist project, which relegates the country’s large Muslim minority to second-class citizens. The parliamentary elections earlier this year returned his BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party) to power, though it lost its absolute majority in the lower house. Nevertheless, there is no indication that Modi will relent in his fascist project. Currently, he is carrying out the most sustained attack on the freedom of the press since the Emergency in 1976 by putting progressive journalists in jail and bringing charges against noted writers like Arundhati Roy.

In Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro lost the 2022 presidential elections to Lula da Silva by a slight margin, but his followers refused to accept the verdict, and thousands of people from the right invaded the capital Brasilia on January 8, 2023, in an attempt to overthrow the new government, in a remarkable replication of the January 6, 2021 insurrection in Washington.

In Hungary, Viktor Orban and his Fidesz party have almost completed their neutering of democracy. Indeed, Europe is the region where fascist or radical right parties have made the most inroads. From having no radical right-wing regime in the 2000s, except occasionally and briefly as junior partners in unstable governing coalitions as in Austria, the region now has two in power—one in Hungary and the government of Giorgia Meloni in Italy. The far right is part of ruling coalitions in Sweden and Finland. The region has four more countries where a party of the far right is the main opposition party. And it has seven where the far right has become a major presence both in parliament and in the streets.

In the Philippines, I wrote two months into Rodrigo Duterte’s presidency in 2016 that he was a “fascist original.” I was criticized by many opinion-makers, academics, and even progressives for using the “f” word. Over seven years and 27,000 extra-judicial executions of alleged drug users later, the “f” word is one of the milder terms used for Rodrigo Duterte, with many preferring “mass murderer” or “serial killer.”

Duterte nevertheless ended his presidency in 2022 with a 75 percent approval rating, and he is now leading the opposition to the administration of President Ferdinand Marcos, Jr., apparently confident he can topple it.

Fascist Charisma and Discourse(s)

Let me spend some time on Duterte since he is the fascist figure I am most familiar with. Like Trump, Bolsonaro, Modi, Orban, Geert Wilders in the Netherlands, and now Javier Milei in Argentina, Duterte is a charismatic figure. Charisma, that quality in a leader that creates a special bond with his or her followers, is not just of one variety. Modi’s charisma is different from that of Duterte. Although Modi’s charisma is more of the familiar inspirational type, Duterte has what I called “gangster charm.” In the way he connects with the masses, in his discourse, Duterte has similarities to Donald Trump, with his penchant for saying the outrageous and delivering it in an unorthodox fashion—precisely what drives their supporters wild.

On Duterte’s discourse while he was president, I would like to share three observations. First, from a progressive and liberal point of view, his discourse was politically incorrect, but that was its very strength. It came across as liberating to its middle-class and lower-class audience. Duterte was seen as telling it as it was, as deliberately mocking the dominant discourse of human rights, democratic rights, and social justice that had been ritually invoked but was increasingly regarded as a cynical coverup for the failure of the post-Marcos liberal democratic regime to deliver on its promise bringing about genuine democratic political and economic reform.

Second, Duterte’s discourse involved a unique application of what Bourdieu calls the strategy of condescension. His coarse discourse, delivered conversationally and with frequent shifts from Tagalog, a Filipino language, to another, Bisaya, to English, made people identify with him, eliciting laughter with his portrayal of himself as someone who bumbled along like the rest of the crowd or had the same illicit desires, at the same time that it also reminded the audience that he was someone different from and above them, as someone with power. This was especially evident when he paused and uttered his signature, “Papatayin kita,” or “I will kill you,” as in “If you destroy the youth of my country by giving them drugs, I will kill you.”

Third, Duterte’s speechmaking did not follow a conceptual or rhetorical logic, and this was another reason he could connect with the masses. The formal conceptual message written by speechwriters was deliberately overridden by a series of long digressions where he told tales in which he was invariably at the center of things that he knew would hold the audience’s attention, even when they had heard it several times. Let me confess here that when I listened to Duterte’s digressions, peppered as they were with outrageous comments, like telling an audience he would pardon policemen convicted of extra-judicial executions so they could go after the people who brought them to court, my mind had to restrain my body from joining the chorus of laughter at the sheer comic effrontery of his words. With Duterte, the digression was the message.

Duterte, of course, is not unique among far-right leaders In his ability to connect to his base by trampling on accepted conversational conventions and admitting to illicit desires. One of the sources of Donald Trump’s appeal is that he, like Duterte, connects, without subterfuge or euphemism, with his white male base’s’ “deeply missed privilege of being able to publicly and unabashedly act on whatever savagery or even mundane racism they wished to,” as Patricia Ventura and Edward Chan put it. To many aggrieved white American males he came across as refreshingly candid in publicly calling Mexicans rapists, Muslims terrorists, colored immigrants as coming from “shithole countries” instead of pristine, white Norway, and boasting that, “When you’re a star, they let you do it. You can do anything. Grab ‘em by the pussy. You can do anything.”

Economics and Fascism

Leaders are critical in fascist movements, but social conditions create the opportunities for the ascent of those leaders. Here one cannot overemphasize the role that neoliberalism and globalization have played in spawning movements of the radical right. The worsening living standards and great inequalities spawned by neoliberal policies created disillusionment among people who felt that liberal democracy had been captured by the rich and distrust in center-right and center-left parties that promoted those policies.

Perhaps, there is no better testimony to the role of neoliberal policies than that of former President Barack Obama, who represents the dominant, neoliberal, “Third Way” wing of the Democratic Party, along with the Clintons. In a speech in Johannesburg in July 2017, Obama remarked that the “politics of fear and resentment” stemmed from a process of globalization that “upended the agricultural and manufacturing sectors in many countries…greatly reduced the demand for certain workers…helped weaken unions and labor’s bargaining power…[and] made is easier for capital to avoid tax laws and the regulations of nation states.” He further noted that “challenges to globalization first came from the left but then came more forcefully from the right, as you started seeing populist movements …[that] tapped the unease that was felt by many people that lived outside the urban cores; fears that economic security was slipping away, that their social status and privileges were eroding; that their cultural identities were being threatened by outsiders, somebody that didn’t look like them or sound like them or pray as they did.” These resentful, discontented masses are the base of fascist parties.

Disenchanted with the Democratic Party’s embrace of job-killing neoliberal policies, the white working class vote put Republican Trump over the top in the traditionally Democratic swing states in the Midwest during the 2016 U.S. presidential elections. But it is not only neoliberal policies that white workers are protesting by walking out of the Democratic Party and walking into the Trump tent; they also feel that professional and intellectual elites have captured their old party, along with Blacks and other minorities.

It is not only the white working class that now forms the base of the Republican Party. Large parts of rural America have long been marked by economic depression, creating ideal ground for the politics of resentment and the incubation of far right militias, who made their intimidating presence felt in the cities where protests against police brutality spread after the killling of George Floyd.

In France, the Socialist Party collapsed, with a significant part of its former working class adherents going to Marine Le Pen and her National Front (now National Rally). Their sentiments were probably best expressed by a Socialist senator who said, “Left-wing voters are crossing the red line because they think that salvation from their plight us embodied by Madame Le Pen…They say ‘no’ to a world that seems hard, globalized, implacable. These are working-class people, pensioners, office workers who say: ‘We don’t want this capitalism and competition in a world where Europe is losing its leadership.’”