HMS Trent

ANALYSIS

By J. Vitor Tossini

- July 14, 2024

In late 2023, tensions between Guyana and Venezuela resurged following the latter’s renewed claims and hostile rhetoric over the Essequibo region, also known as “Guayana Esequiba.”

This region represents roughly 74% of Guyanese territory and 16% of its population. In response, Guyana sought support for its territorial integrity from the United States, the United Kingdom, Brazil, and others.

A crisis was temporarily averted after backing from Washington, London, and neighboring states for de-escalation. For Britain, however, a hotspot in the only Commonwealth member in South America leaves the country in a difficult position.

This article is the opinion of the author and not necessarily that of the UK Defence Journal. If you would like to submit your own article on this topic or any other, please see our submission guidelines.

Although the United States holds a preeminent stance over the region, if inaction from London is the primary response to a close partner asking for political support, the signaling to others might be counterproductive to the ambitions of a true Global Britain.

Historical Context

British Presence in Guyana

The British presence in the region of present-day Guyana goes back to the 1740s when the Dutch allowed British immigrants into the area near the Demerara River. The promise of land ownership attracted plantation owners from Britain’s Lesser Antilles, and within two decades, the British represented most of the Europeans in the Dutch Demerara.

When the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War (1780-1784) broke out over disputes concerning Dutch trade with British enemies in the American War of Independence, Britain briefly occupied the territory but was expelled by French forces. France maintained control of the colony until 1784 when it was handed back to the Dutch, which continued with the policy of chartering Demerara to the Dutch West India Company until 1792. However, the political influence of the British landowners had already become significant, and by the mid-1780s, the colony’s internal affairs were managed mainly by British subjects.

United Colony of Demerara and Essequibo

After the end of Company rule in 1792, the Dutch created the United Colony of Demerara and Essequibo, which came under the direct control of the Dutch Government while a separate colony was maintained for the Berbice River settlement. During the French Revolutionary Wars, the French occupation of the Netherlands in 1795 contributed directly to the successful and bloodless 1796 British expedition to take both Dutch colonies. The Treaty of Amiens briefly returned the two colonies to the Dutch at the end of the Second Coalition War.

Uninterrupted British rule would commence in 1803 when Britain terminated its uneasy truce with France. Shortly after the British declaration of war in May 1803, a force was dispatched to capture the Dutch colonies for the third and final time. Through the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814, the United Netherlands formally transferred Essequibo, Demerara, and Berbice to the United Kingdom. Importantly, the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814 did not stipulate the borders of the Dutch “settlements” ceded to the British, opening the way for future territorial disputes.

Emergence of Gran Colombia and British Guiana

The emergence of the independent Gran Colombia from the former Spanish territories of the Viceroyalty of New Granada led to contested claims as early as 1822, with complaints from Gran Colombia regarding the British colonization of claimed territories west of the Essequibo River. In 1831, Britain merged its colonies in the region, creating the colony of British Guiana.

A decade later, the first British attempt at delimitation of Guiana’s borders resulted in the Schomburgk Line, named after explorer and naturalist Robert Hermann Schomburgk, who was responsible for a botanical and geographical exploration of the territory in 1835. The Line set the overall tone of the territorial disputes with Venezuela – after the dissolution of Gran Colombia in 1839 – except for envisaging British Guiana reaching as far as the mouth of the Orinoco River. In 1850, although Britain and Venezuela agreed not to colonize the disputed territory, both countries refrained from defining the borders of the contested area.

Gold Reserves and Renewed Claims

During the next 26 years, the dispute remained dormant until gold reserves were discovered in 1876 and quickly explored by British-backed settlers. Venezuela renewed its original claims up to the Essequibo River. Britain’s response was a counterclaim covering the Schomburgk Line and all of the Cuyuni Basin, although the claims over the latter were essentially political. In late 1886, the British Government adopted the Line as the provisional western border of British Guiana, which led to Venezuela breaking diplomatic relations and seeking American support.

The United States did little for years until Venezuela hired William L. Scruggs as a lobbyist in Washington. Shortly after, tensions erupted in the form of the Venezuelan Crisis of 1895. Initially, London refused to subject the entire disputed territory to calls for arbitration. However, Scruggs’ influence in Washington and argumentation that Britain had violated the Monroe Doctrine led to American solid support for arbitration of the disputed territory.

Arbitration and Controversy

The 1899 Arbitration

By December 1895, the crisis had shifted from disagreements between London and Washington to a presidential address to Congress, which was seen as a threat to the British if they did not accept arbitration. In Britain, the matter’s relevance for the United States only began to be recognized after December. In January, the British Government accepted arbitration in principle and removed previous demands, including that any arbitration should use the Schomburgk Line as the basis for future negotiations.

Despite conceding to the proposal, the British managed to convince their American counterparts about several points, including the number of members of the future Panel of Arbitration. The British case rested on the argument that before the independence of Venezuela, Spain had not taken “effective possession” of the territory in question and that the Dutch had several arrangements and alliances with local Native Americans, which in practice gave the Dutch a sphere of influence that was transferred to Britain in the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814.

However, the British argumentation received little support among the sitting American members of the Tribunal of Arbitration. Meanwhile, Britain and Venezuela formalized the procedures and signed the Treaty of Washington, agreeing to respect the decision of the Tribunal as the “perfect, and final settlement” to the dispute.

The Tribunal’s Decision

The Tribunal’s decision was disclosed in October 1899, awarding Venezuela only slightly more than 10% of the disputed territory and granting Britain the remaining area. Most of the Schomburgk Line remained as the border, with the main alterations being changes near the mouth of the Orinoco River, granted to Venezuela.

The Tribunal of Arbitration gave no reasoning for its decision. Although perceived as a national defeat, the Venezuelan Government accepted the ruling. A commission surveyed the new border, and both parties accepted the verdict in 1905.

Renewed Disputes and the Geneva Agreement

Mallet-Prevost Memorandum

The dispute would arise again more than half a century after the 1899 Arbitration decision. In 1949, the Mallet-Prevost memorandum was posthumously published. Its author, Severo Mallet-Prevost, official secretary of the American and Venezuelan delegations during the 1899 Arbitral Award, stated that the favorable ruling towards Britain resulted from a deal between the British and Russian governments. The deal supposedly involved the Russian representative of the five-member arbitration panel, Friedrich Martens, granting the British a 3 to 2 majority; as the British side had two sitting members, the Venezuelan-American had another two, and Friedrich Martens was the independent fifth member.

Mallet-Prevost explained in his memorandum that the US-Venezuela judges were forced to choose between a “consensus deal” that would grant Venezuela some relevant stretches of land while agreeing with British possession of the remaining area or face a 3 to 2 decision that would be even more favorable to Britain. Mallet-Prevost’s memorandum reinforced the suspicions in Venezuela that the 1899 Arbitral Tribunal had been unjustifiably one-sided. The South American country promptly revived its claims over the then-British Guiana. In the mid-1950s, Venezuela, under a military dictatorship, initiated plans to invade and annex Essequibo, but the dictator – Marcos Pérez Jiménez – was overthrown, and democracy was restored before the invasion commenced.

Bringing the Matter to the United Nations

In 1962, based on the Mallet-Prevost memorandum, Venezuela brought the matter to the United Nations, arguing that the 1899 decision was null and void. Although Venezuela could not provide additional documents to prove its case, the UK agreed to engage in new conversations, mainly due to ongoing plans to disengage from British Guiana. In November 1963, representatives of Venezuela, the UK, and British Guiana met in London.

The result was a communiqué declaring that all parties should work to “Find satisfactory solutions for a practical settlement of the controversy which has arisen as a result of the Venezuelan contention that the 1899 award is null and void”. A high-profile meeting occurred in the following month with similar results. The British and Guianese agreed to “find satisfactory solutions” to the alleged nullity of the 1899 decision, which means finding evidence that corroborates the Venezuelan calls for nullity.

The Geneva Agreement

Following these meetings, negotiations started for what would be known as the 1966 Geneva Agreement between the United Kingdom – on behalf of British Guiana, independent in May 1966 – and Venezuela. Signed in February 1966, Article I reiterated the aim to search for “satisfactory solutions for a practical settlement of the controversy between Venezuela and the United Kingdom, which has arisen as the result of the Venezuelan contention that the Arbitral Award of 1899 about the frontier between British Guiana and Venezuela is null and void.”

Simply put, the core aim of the Agreement remained the same as the communiqué signed almost three years before. However, in the Agreement, there were no concessions over the sovereignty of the disputed territory, and all parties agreed to make no further claims or enlarge existing claims. They also established a four-year period for the resolution of the dispute. Notably, through Article VIII, Britain tied itself to the question of still being a part of the Agreement even after the independence of British Guiana, with lingering expectations from Guyana as an independent nation. In this regard, as Dr. Odeen Ishmael, former Guyanese ambassador, stated: “Great Britain has never handed over its rights as a party to the Guyana government, and must, therefore, play an active role in resisting any claim by Venezuela to Guyana’s territory”.

Geneva Agreement Violations and the Port of Spain Protocol

Lastly, the Geneva Agreement states that if the parties fail to find a solution to the case through a Mixed Commission, they shall refer the decision to the “appropriate international organ upon which they both agree or, failing agreement on this point, to the Secretary-General of the United Nations”.

It is worth mentioning that this would influence the 2020 decision of the Secretary-General to send the matter to the International Court of Justice (ICJ). Four months after the independence of Guyana, Venezuela performed the first violation of the Geneva Agreement when it invaded the Guyanese part of Ankoko Island, quickly building facilities to support a military garrison on the occupied territory. After the expiration of the Mixed Commission in 1970, Venezuela and Guyana agreed on a protocol to the Geneva Agreement.

In short, the 1970 Port of Spain Protocol was a 12-year moratorium on the border dispute, a temporary suspension on Venezuela’s claims over the Essequibo, that would allow the two sides to foster cooperation and partnership without the shadow of territorial disagreements. The Protocol was signed by representatives of three parties of the Geneva Agreement, meaning that Britain remained involved in the question. Nevertheless, adverse reactions in Venezuela resulted in the Port of Spain Protocol not being renewed when its deadline expired. Shortly after the Protocol’s expiration in 1983, Venezuela declared interest in reopening bilateral talks with Guyana without the involvement of third parties.

A counter-proposal accompanied the Guyanese rejection, which involved taking the case to the United Nations General Assembly, the Security Council, or the International Court of Justice. Venezuela repudiated the proposals, and the dispute remained unchanged until four years later. In that year, both countries accepted the Good Offices method of settling international disputes, in which a third party, with the consent of the disputing states, serves as a neutral mediator between the governments to aid them in achieving a solution. Since 1989, the intermediary has been a representative of the Secretary-General of the United Nations.

Recent Developments and Renewed Tensions

Oil Discoveries and Increasing Tensions

Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, the issue continued under the auspices of a representative of the Secretary-General. Signs that the contention had been thawing out in the last decade could be seen when Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez visited Georgetown in 2004, declaring the dispute to be finished. The situation would start changing in 2006 after Venezuela altered its flag to include an eighth star symbolizing the Essequibo region.

Any prevailing doubts about Chávez’s actual position on the dispute were lifted in 2011 when Guyana submitted an application to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf to extend its continental shelf by a further 280 kilometers (150 nautical miles). Considering the dispute essentially over, Guyana made its application, knowing that the Commission only analyzes cases of areas that are not subject to territorial disputes. Ending pretenses that an accommodation to the case was closed, Venezuela sent an objection to the Commission stating that the Guyanese application had areas subject to an ongoing unsettled international sovereignty dispute.

The following decade would witness renewed tensions, particularly from the Venezuelan side, fostered by growing prospecting for oil in Guyanese territory. In 2013, a vessel conducting exploration for oil on behalf of the Guyanese Government was detained by Venezuela, triggering a minor diplomatic crisis. Three years later, Guyana granted a license to drill for oil in an area offshore the Essequibo to the American multinational ExxonMobil. Within a few months, it was clear that Guyana and its Economic Exclusive Zone (EEZ) had promising oil reserves. Despite protests from Caracas and the inclusion of the disputed maritime zone as part of a Venezuelan marine protection area, Georgetown authorized further drillings. Significant discoveries started to happen in 2017.

ICJ Involvement and Economic Transformation

Meanwhile, the Secretary-General of the United Nations, António Guterres, argued that the dispute had not seen “significant progress” in decades. The Secretary-General also stated that he intended to hand the case to the International Court of Justice if there was no explicit objection from both sides. In 2018, Guterres handed the case to the ICJ – with Guyana’s support – on whether the 1899 Arbitration was valid and stated that the Good Offices practices were insufficient to reach an agreement.

While the ICJ analyzed the question, crude oil production started in 2019. Within four years, the offshore area of the Essequibo – known as the Stabroek block – propelled Guyana to become one of the largest crude oil producers, only behind the United States and Brazil in the Americas and ahead of Norway and China. As the US Energy Information Administration stated: “Since starting production in 2019, Guyana has increased its crude oil production to 645,000 barrels per day (b/d) as of early 2024, all from the Stabroek block.” Guyana’s crude oil production grew rapidly, with an annual 98,000 b/d increase on average between 2020 and 2023.

Consequently, the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) experienced unparalleled growth, with a 49% increase in 2020. By 2022, the GDP grew an additional 62.3%, making Guyana, by some metrics, the fastest-growing country in the world. In 2024, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) expected Guyana to remain the fastest-growing country worldwide, with growth above 30% due to its oil and gas boom. Guyana has witnessed a quick and sharp economic transformation, with significant improvements to its Human Development Index and the purchasing power of its population.

Renewed Hostilities

Within this context of a golden age for the economy of Guyana reappeared the belligerent and sabre-rattling posture of a Venezuela engulfed by economic and political problems. Between the submission of the case to the ICJ in early 2018 and the Court’s ruling that it had jurisdiction to determine the territorial dispute in early 2023, the whole process was criticized by Venezuela, which abstained from partaking in the proceedings of the ICJ, including hearings and submission of argumentation. On 18 October, reports of an increased Venezuelan military presence near the contested border prompted Guyana to question its neighbor through diplomatic channels.

The 2023 crisis would only erupt on 23 October 2023 – roughly one month after Guyana granted new offshore drilling licenses – with the Venezuelan Government increasing the hostility of its rhetoric with the proposal of a referendum to oppose “by all means” Guyana’s use of the Economic Exclusive Zone off Essequibo and give Venezuelan citizenship to the population of Essequibo, dated to occur on 3 December 2023. Shortly after, on 31 October, Guyana submitted a request to the International Court of Justice requesting a position on Venezuela’s behavior. Two days before the referendum, the Court ruled that Venezuela should take no actions to alter the status quo while the Court analyzed the case.

In the weeks before the referendum, Guyana sought support from its traditional partners, mainly the United States, Britain, and neighboring states. As the vote in Venezuela approached, Guyana gathered support for its territorial integrity from Brazil, Britain, the United States, the Caribbean Community, the Commonwealth of Nations, and others. Additionally, Guyana’s Prime Minister Mark Anthony Phillips accused Venezuela of “considerably expanding its military forces” near the border and gathered support from Brazil, the United States, and the Secretary General of the Organization of American States.

On 14 November 2023, an initiative by the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States successfully held a meeting with the leaders of Guyana and Venezuela and officials from the United Nations. Both sides agreed not to resort to the use of force or escalate tensions while stating that they decided to settle the issue in accordance with international law. However, the same statement declared that Venezuela does not recognize the ICJ’s jurisdiction over the dispute.

Despite diplomatic moves to ease tensions, the referendum occurred on 3 December. Soon after, the Venezuelan Government declared that 95% of voters supported the questions in the ballot, claiming it had a renewed mandate to incorporate the Essequibo region. International analysts questioned the referendum’s validity, pointing out the likelihood of Caracas falsifying the results.

The turnout was also meagre for Venezuela. Within a week, the Venezuelan President, Nicolás Maduro, stated that he had already initiated proceedings to incorporate the region, but the whole process could take a few years. It is worth noting that the referendum and other attempts to change the status quo violated the 1966 Geneva Agreement.

Three days after the referendum, the Brazilian Army reported that it had detected an increase in Venezuelan troops near the border with Guyana and that the Brazilian Government had been taking actions to increase the number of its forces near the Brazilian border with Venezuela and Guyana. Shortly after, Brazil issued a statement renewing its support for Guyana’s territorial integrity and a peaceful solution to the dispute. At this stage, Brazil feared being dragged into a conflict if Venezuela used the more accessible land routes to Guyana by crossing Brazilian territory.

In practice, this meant that Maduro lost sympathy from the only major country in South America that he hoped to stay – at least – neutral and desired to court to his side. The Brazilian Government was also worried that Venezuela’s behavior would lead to the establishment of foreign military bases in Guyana. Hence its unequivocal support for peaceful solutions, de-escalation, and the efforts to act as an intermediary between the two parties.

International Responses

British and American Involvement

Four days after the vote, the United States announced that it would dispatch military forces to participate in joint operations with their Guyanese counterparts to improve cooperation in security measures. On 18 December, Britain was the first Group of Seven (G7) country to dispatch a minister to Guyana since the renewed tensions in October. The Minister for the Americas, Caribbean, and Overseas Territories, David Rutley, declared he was there “to offer the UK’s unequivocal backing to our Guyanese friends” and that “the border issue has been settled for over 120 years.”

The Minister also stated that “the UK will continue to work with partners in the region, as well as through international bodies, to ensure the territorial integrity of Guyana is upheld.” The visit was the second of the Minister for the Americas to Guyana in 2023. As part of efforts to improve bilateral trade between Britain and Guyana, Rutley was present in March 2023 when the British Chamber of Commerce was officially launched in the country.

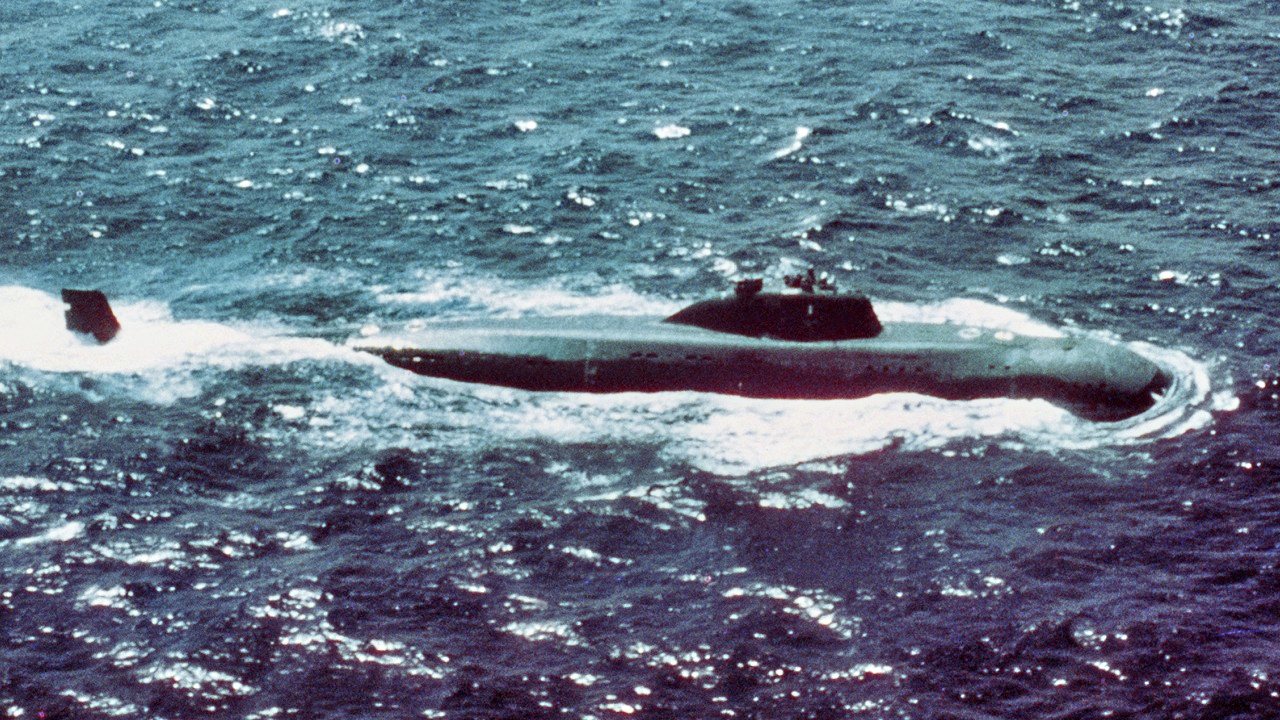

Shortly after the visit of the British Minister for the Americas and the United States announcement of joint exercises with Guyana, on 24 December, the British Government stated that a Royal Navy vessel would be deployed to the country as part of joint operations with Guyana’s defense forces.

The vessel in question was the Offshore Patrol Vessel (OPV) HMS Trent, deployed to the Caribbean to assume patrol duties from her sister ship, HMS Medway, while her maintenance in Gibraltar was underway. Venezuela’s reaction included declarations about Britain bringing instability to the region and ordering a “defensive” military exercise near the border, with roughly 6,000 personnel involved. Despite the Venezuelan rhetoric and attempts at military displays of force, HMS Trent conducted her duties with her Guyanese counterparts without disturbance.

Continued Military Buildup and Diplomatic Efforts

Although Venezuela and Guyana continued to hold meetings – with Brazilian mediation – into 2024, reports of a military buildup on the Venezuelan side of the border permeated most discussions after the referendum. In early April 2024, Maduro signed into law the creation of a Venezuelan province in what is the Essequibo, weakening ongoing diplomatic efforts to minimize tensions.

By mid-2024, Venezuela continued to expand its military infrastructure near the border with Guyana. Meanwhile, the United States has pledged to assist Guyana in acquiring new military equipment, including aircraft, helicopters, drones, and radar technology. In June, in another display of growing American commitment and interest, Under Secretary Jenkins visited Guyana to discuss issues concerning, among other things, “international security.” Similarly, numerous Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) officers have visited the country since December 2023.

Positions of Key International Players

The dispute also questioned the position of Venezuela’s main diplomatic and economic partners, particularly China. For China, the dispute could potentially disrupt its expanding investments in Guyana’s oil fields, with Chinese oil companies having a 25% stake in the Starbroek oil block, only behind the American ExxonMobil (45% stake) and Hess (30%). Venezuela’s position as a supplier of crude oil and buyer of Chinese security and military assets further complicates China’s stance.

Thus, between 2023 and 2024, China has attempted to follow a middle ground, aiming to keep both sides pleased. The Russian position is relatively simple when compared to the Chinese. Russia’s stance can be described as mimicking Venezuelan arguments and claims, offering tacit support for Maduro’s ambitions.

The British-Guyanese Connection

Economic and Political Ties

The shared history of Britain and Guyana contributes to the view in Georgetown that London remains a relevant partner. Despite the relative decline of the British economic influence in South America and the Caribbean, Britain is still a relevant partner with strong economic ties with some regional countries, particularly Commonwealth members. Guyana is one of these regional partners, traditionally having Britain as one of its largest trading partners.

According to the British Department of Business and Trade, between 2013 and 2022, the total bilateral trade with Britain accounted for roughly 8.7% of Guyanese trade on average and has been on the rise since the discovery of oil. By 2023, crude oil represented more than 95% of British imports from the South American nation. British exports to Guyana were marked by “road vehicles other than cars” (34%), “general industrial machinery” (17.3%) and “specialized machinery” (16.9%).

British exports to the country in the first quarter of 2023 grew by 96.5% compared to 2022. In 2023, total trade of goods and services reached £1.8 billion, a rise of 50% compared to 2022, with almost £950 million of trade surplus for Britain. Between 2016 and 2023, trade expanded fifteenfold. Thus, the tendency is one of increased Anglo-Guyanese trade as Guyana expands its oil production capacity and the demand for machinery and know-how to manage its growing economy. Although a relatively small economy, Guyana has the potential to become a reliable source of crude oil imports for Britain, easing the pressure on the vital sea lanes in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean. Nevertheless, strengthening bilateral relations – economically and politically – will demand a renewed policy for the region.

Strategic Considerations

As Maduro marches on with his jingoistic rhetoric, Britain’s interests in Guyana are caught within a moment of rising stakes. The only Commonwealth member in South America with significant potential as a reliable economic partner has already called Britain for support in its question to maintain its territorial integrity. Besides seeing Britain as an important economic and political partner, possibly helping the country to advance into the era of the “oil boom,” Guyana also recognizes Britain as tied to the border question due to the

British not relinquishing their position as one of the parties of the Geneva Agreement. Moreover, Britain’s support means that Guyana has more than one major country on its side, while Venezuela is emboldened mainly by Russia. For Britain, the question of Guyana and the Essequibo is one of recognizing that – even if Venezuelan aggression might be a distant concept – British support remains highly relevant to the dispute, and providing useful support to Guyana’s territorial integrity is mutually beneficial, allowing the British economic presence in the country to grow and contributing to Guyana itself benefiting from its natural resources with political stability.

Conclusion

The dispute over the Essequibo might be overlooked, but it is still an opportunity to prove that Britain is truly “global” and willing to reinforce links with old partners. In addition, the case of Guyana reinforces the view that the international arena of the 2020s is quickly becoming increasingly more competitive and unstable than it was in the 1990s or 2000s. Nevertheless, despite rhetoric acknowledging the changes, British defence and foreign policy struggled to break free from the mindset of the 1990s. As the sources of instability that threaten or challenge British global interests multiply, the Government in London must understand that ensuring national security and defending British interests are tasks that ultimately demand investment and cannot be run cheaply.

This is particularly the case about topics not entangled by a formal British network of alliances and security pacts. Even when considering interests supported by alliances, a prepared Britain will have a loud voice in a crowded room of allies to help decide how to achieve shared objectives. When considering the British position and interests internationally, the Essequibo dispute might initially appear secondary at best. However, an underlying issue remains: similar crises are likely to erupt elsewhere, and when British interests are involved, the UK’s peer competitors will take notice of the British stance and actions.

J. Vitor Tossini

Vitor is a doctoral student of International Relations at the Sao Paulo State University. He also explores British imperial and military history, and its legacies to the modern world.